Volume 13, Issue 3 (Summer 2025)

Iran J Health Sci 2025, 13(3): 213-220 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: IR.IAU.SRB.REC.1403.128

Clinical trials code: IR.IAU.SRB.REC.1403.128

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Memarpour L, Pordelan N, Borna S. Effect of Compassion-focused Therapy on Self-value, Cognitive Flexibility, and Marital Stress of Iranian Female Healthcare Workers. Iran J Health Sci 2025; 13 (3) :213-220

URL: http://jhs.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-1011-en.html

URL: http://jhs.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-1011-en.html

Department of Education and Counseling, SR.C., Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran. , pordelan@srbiau.ac.ir

Full-Text [PDF 687 kb]

(519 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1306 Views)

Full-Text: (313 Views)

Introduction

Studies have shown that work is a significant source of stress [1], and this stress is even greater in occupations related to healthcare workers [2]. Stress is a natural feeling and physiological response to internal or external stressors. Due to work-related stress, individuals become irritable, experience high levels of anxiety, and face increased emotional tension, cognitive processes, and changes in physical conditions. Work-related stress is thus defined as a response to a situation in the workplace that negatively affects employees, disrupts their lives, and causes physiological and psychological changes in them [3]. Healthcare workers face various work-related stressors that may affect their different aspects of lives [4]. Healthcare workers face life-threatening hazards and diseases associated with excessive work. Demanding work schedules, administrative correspondence, handling complex and sometimes malfunctioning tools, power hierarchies, expectations, and patient mortality cause them to experience high levels of stress in both workplace and personal life [5]. Healthcare-related jobs can affect marital stress [6]. Marital stress depends on several factors, including communication with a partner, receiving love, spousal support, religiosity, and marital satisfaction [7]. Marital satisfaction is influenced by stress [8, 9], and there is a positive relationship between stress and marital satisfaction [10].

The self-worth theory explains that an individual’s primary priority in life is to achieve self-acceptance, which is often attained through success. Self-worth is a self-evaluation construct that reflects an individual’s overall assessment of their value as a human being [11]. Brown argues that self-worth is not a decision, but an emotion based on feelings of self-compassion, not on ruthless scrutiny of what is not [12]. Cognitive flexibility is a key psychological concept explored in various fields. It refers to the capacity to adapt effectively to new conditions and changing situations. Studies have found a strong connection between cognitive flexibility and self-regulated learning, which involves the ability to control and manage one’s thoughts, emotions, and behaviors in pursuit of specific goals [13].

One therapeutic approach that can be applied to reduce work-related stress is compassion-focused therapy (CFT) [14]. Self-compassion can be considered a skill that can be learned [15]. The CFT believes that the positive attributes of compassion observed in the external world, which bring comfort and tranquility to individuals, should be internalized so that they can calmly manage their inner experiences and better deal with external challenges [16]. In this therapy, individuals learn not to escape from or suppress their undesirable feelings, which plays a crucial role in reducing negative thoughts [17]. The use of CFT has been extensively studied in psychology, and its effectiveness has been examined by various studies, which reported positive outcomes of this therapeutic approach [18, 19]. For example, Navab et al. [20] in a study found that CFT reduced psychological symptoms in Iranian mothers of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Vidal and Soldevilla [19] in a meta-analysis study reported that CFT reduced self-criticism and self-soothing. In this regard and given the important role of healthcare workers, the present study aimed to investigate whether CFT has a significant impact on self-worth, cognitive flexibility, and reduction of marital stress in Iranian female healthcare workers.

Materials and Methods

This is a quasi-experimental study with a pre-test/post-test design. The study population comprised all staff of Imam Khomeini Hospital in Tehran, Iran. Based on the recommendations that at least 15 participants per group are needed for experimental studies [21], a total sample size of 30 individuals was determined. Participants were selected using a voluntary sampling method and randomly assigned to two equal groups: Intervention (n=15) and control (n=15). The inclusion criteria were being female, being a healthcare worker, having at least one year of work experience, and willingness to participate in the study. Participants were excluded if they showed a lack of interest in continuing participation, provided incomplete responses to the questionnaires, or were absent from more than two sessions. To ensure ethical considerations, the purpose of the study was explained to all participants, and they were assured that their personal information would remain confidential and would only be used for research purposes. They could leave the study at any time.

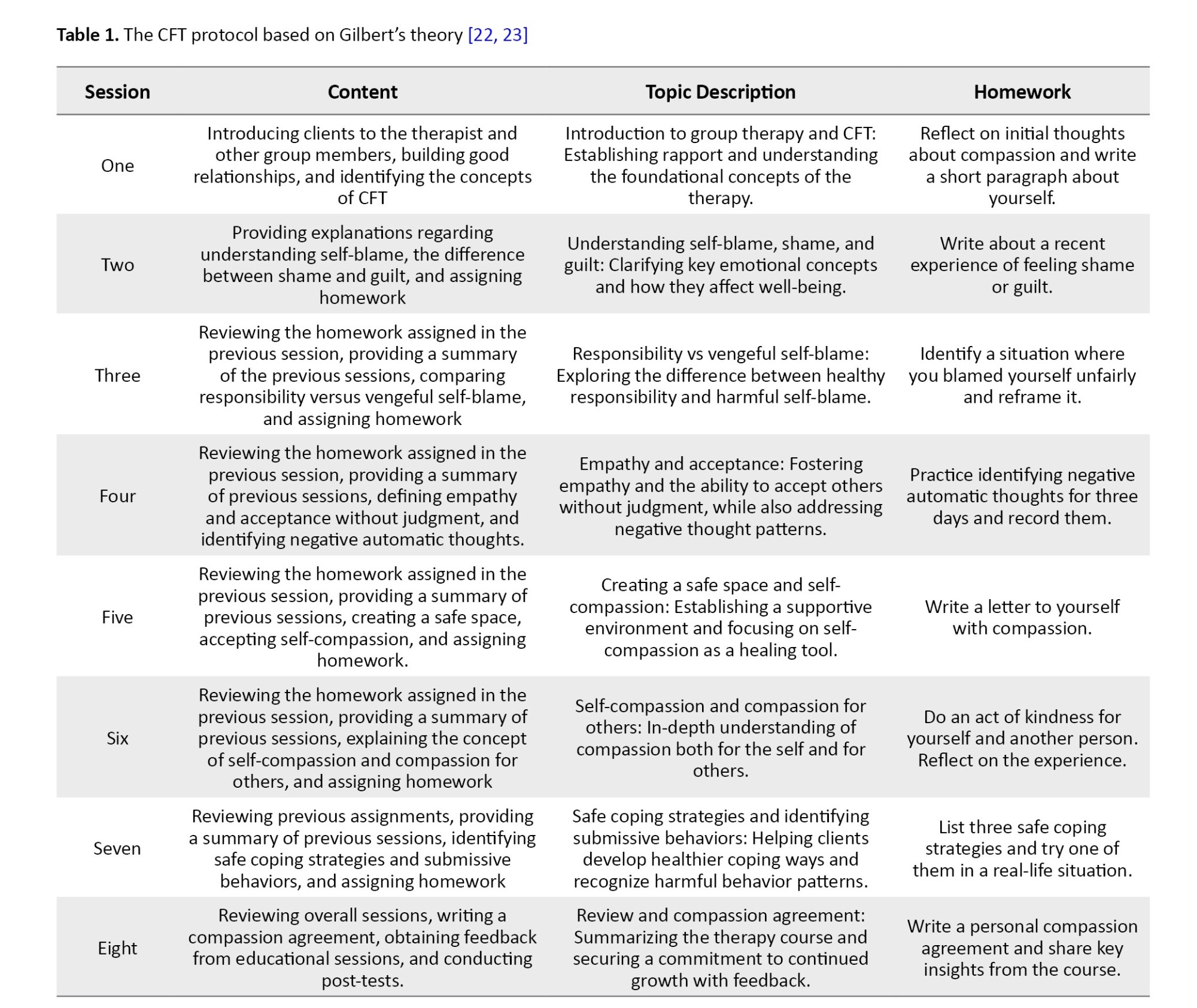

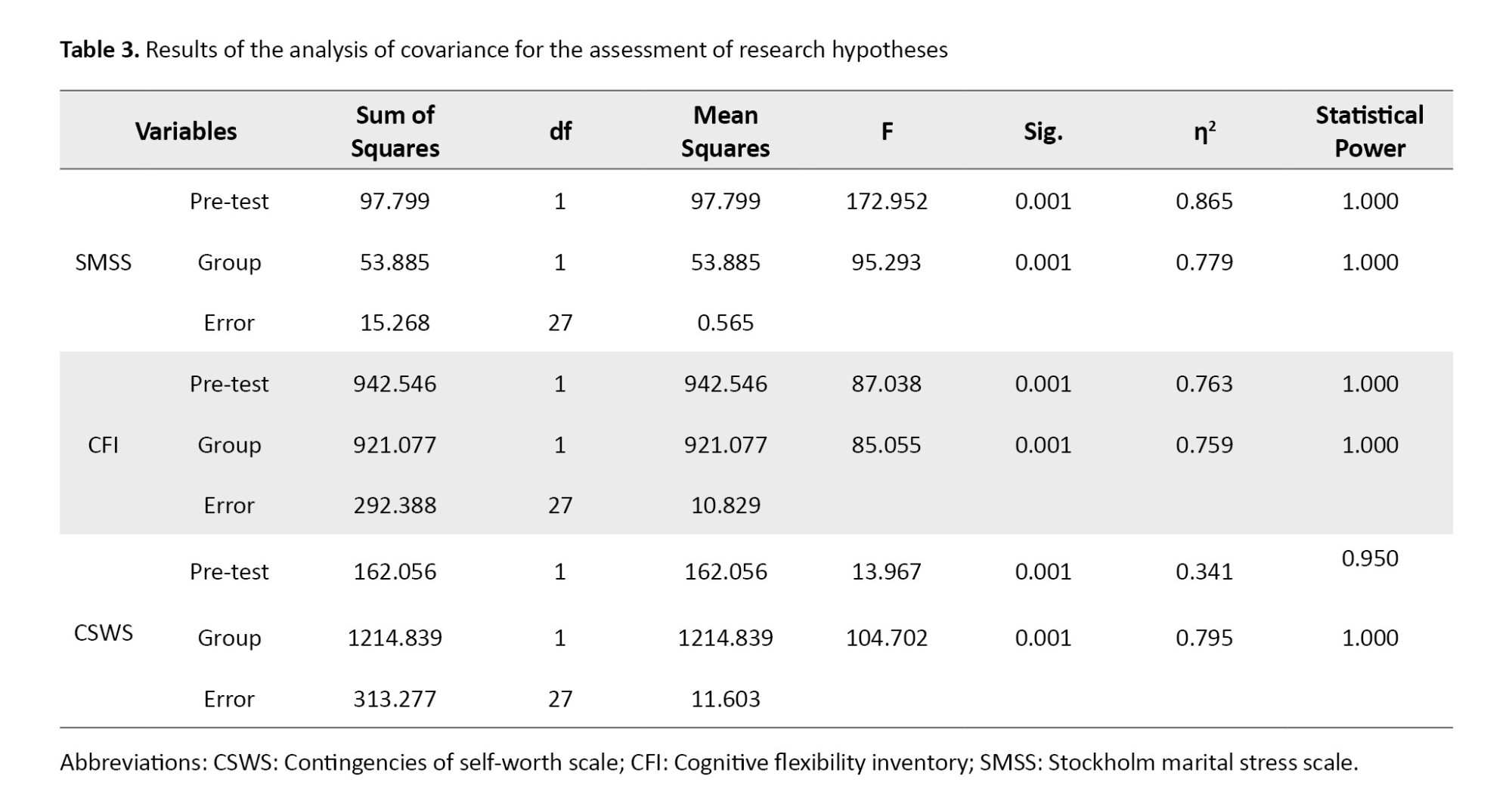

The intervention was provided based on Gilbert’s CFT protocol [22, 23], which emphasizes developing self-compassion, reducing self-criticism, and enhancing emotional regulation through structured therapeutic techniques. The program was delivered at eight weekly sessions, each with specific objectives such as introducing CFT concepts, addressing self-blame and shame, fostering empathy, creating a safe emotional space, and building strategies for coping and self-care. A detailed summary of the sessions is presented in Table 1.

In this study, three questionnaires were used for data collection. A demographic form was used to survey age, marital status, and work experience. The contingencies of self-worth scale (CSWS), developed by Crocker et al. [24], was used to assess self-worth. It has 35 items rated on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), and seven subscales: Family support, competition, physical appearance, God’s love, academics, virtue, and approval from others. In this questionnaire, items 4, 6, 10, 13, 15, 23, and 30 have reversed scoring.

The total score ranges from 35 to 245, with higher scores indicating higher self-worth. The Persian version of this questionnaire was validated by Zaki [25], with a Cronbach’s α of 0.70 for male high school students and 0.83 for female high school students. In this study, self-worth refers to the total score of Persian CSWS. The cognitive flexibility inventory (CFI), developed by Dennis and Vander Wal [26], was also used in this study. It is a short self-report tool with 20 items used to measure a type of cognitive flexibility necessary for individual success in challenging negative thoughts and replacing them with positive ones. The items are scored on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 7 (completely agree).

It has a concurrent validity of -0.39 with the Beck depression inventory and a convergent validity of 0.75 with Martin and Rubin’s cognitive flexibility scale. For the Persian version, a test re-test reliability of 0.71 and a Cronbach’s α value of 0.90 for the entire scale have been reported [27, 28]. The Stockholm marital stress scale (SMSS), developed by Orth-Gomér et al. [29], was used to measure marital stress. It consists of 17 items scored by 0 or 1, with higher scores indicating higher marital stress. It has a Cronbach’s α value of 0.77 and satisfactory construct validity. The Persian version of this scale was validated by Noroozi et al. [30]. After collecting data before and after the intervention, they were analyzed using descriptive and inferential tests in SPSS software, version 26.

The variables were described using central tendency and dispersion indices. The analysis was done using the analysis of covariance. To assess the normality of the data distribution, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests were used. Since P>0.05 in both tests, the assumption of normality was accepted. The homogeneity of variances between the groups was also assessed using Levene’s test. Since the results were not significant (P>0.05), the assumption of homogeneity of variances was confirmed.

Results

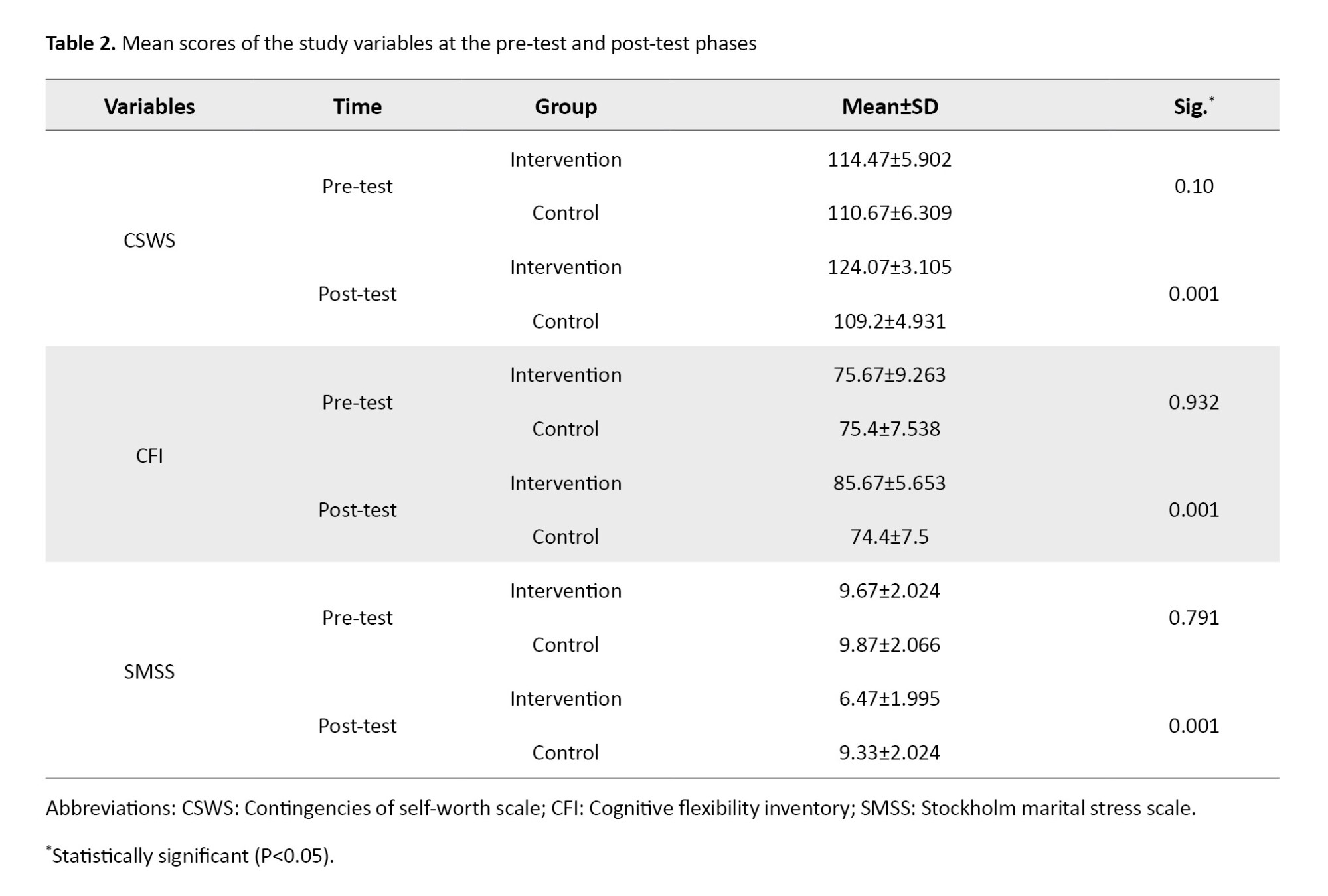

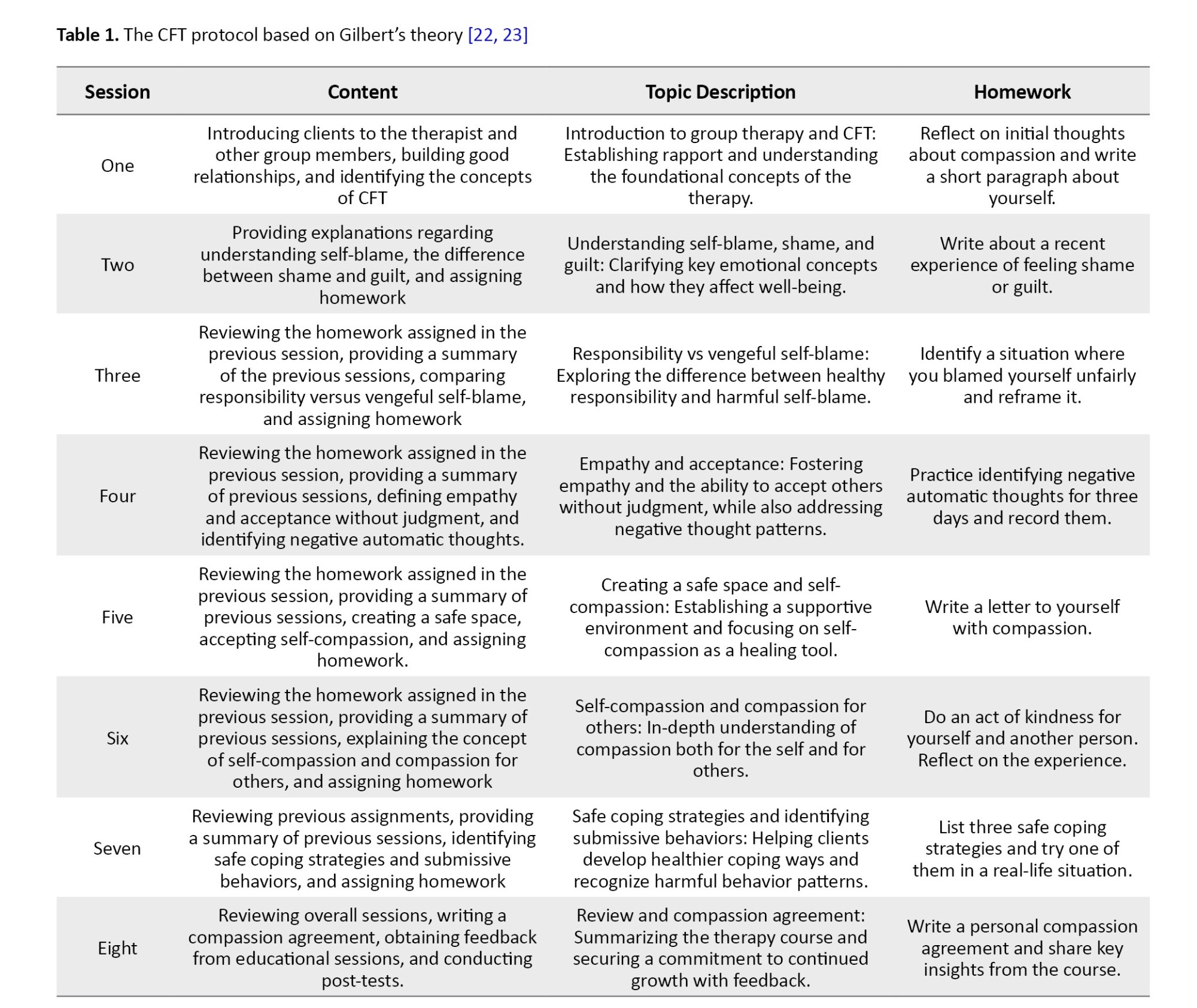

The mean age of the participants was 32.45±5.80 years, and their average work experience was 8.75±4.20 years. In terms of marital status, 65% were married and 35% were single. Table 2 presents the mean scores of the study variables for each group at the pre-test and post-test phases. As shown in the table, the mean values of pre-test scores for each variable were similar between the two groups in the pre-test phase (P>0.05), while significant differences between the two groups were observed in the post-test phase (P<0.05). Therefore, it can be stated that the mean values of the research variables showed differences in the post-test.

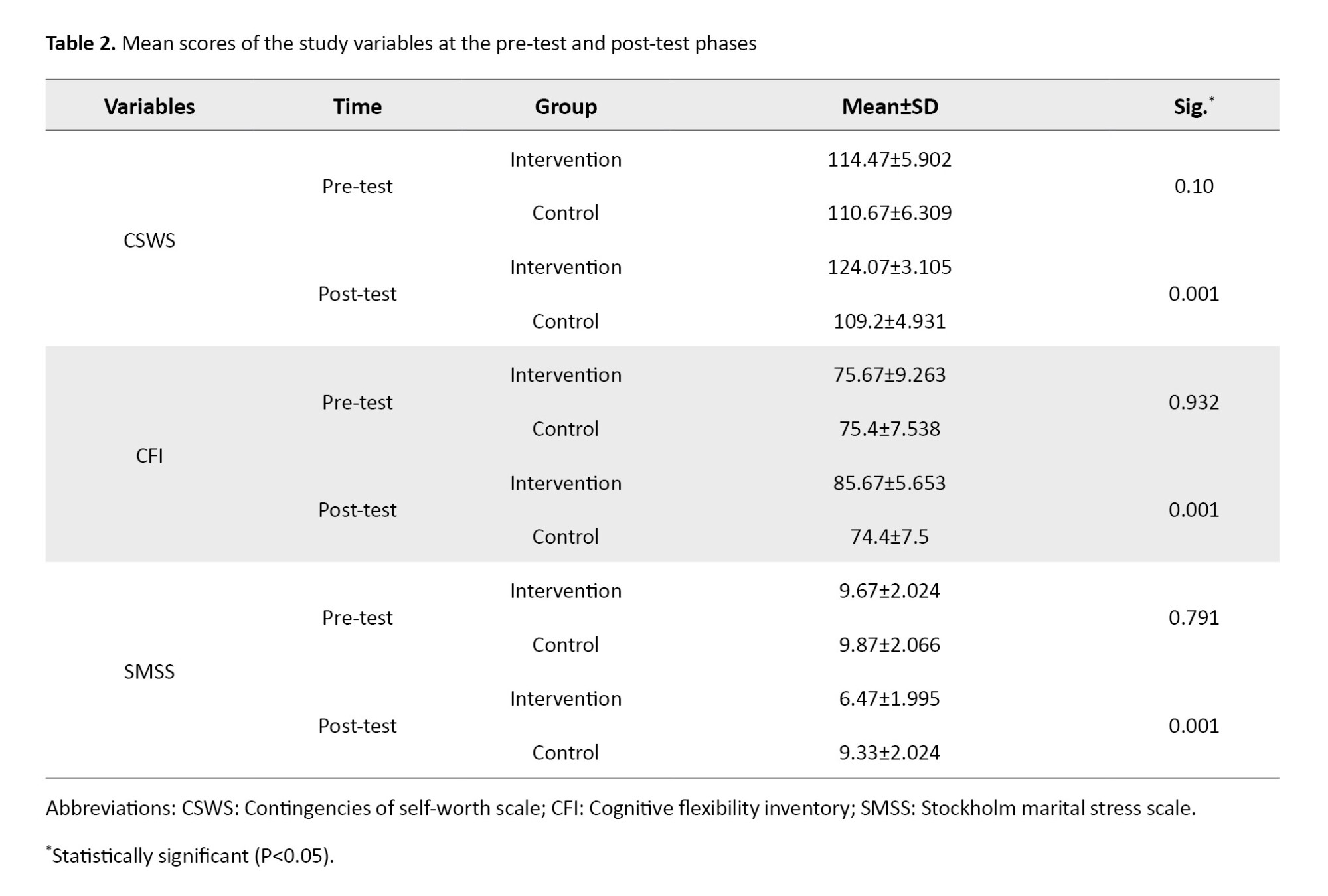

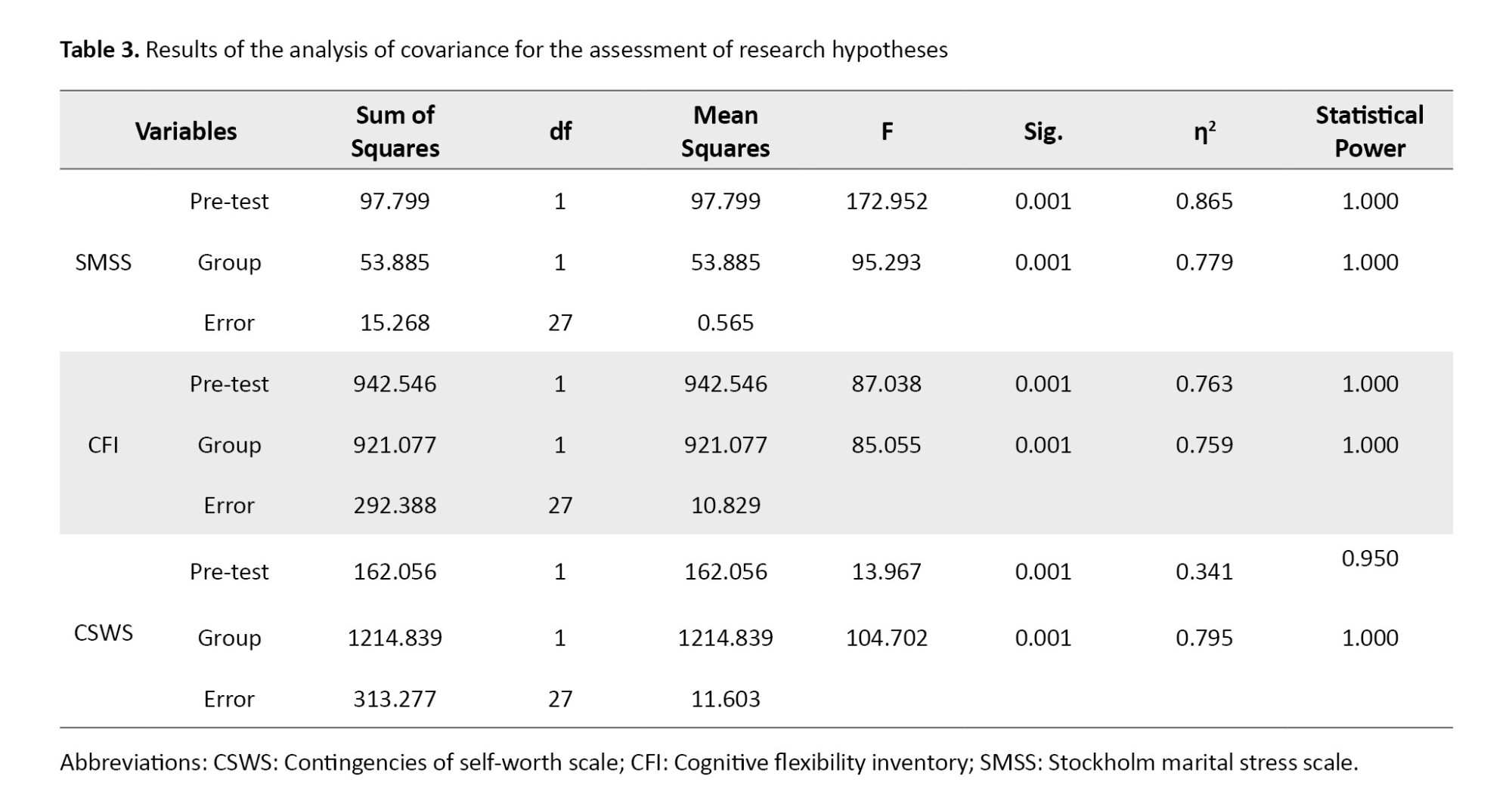

To examine the statistical significance of this difference, the analysis of covariance test was used. The results are presented in Table 3. As shown in the table, considering the pre-test as a covariate, there was a significant difference (P<0.05). The CFT had an effect size of 78% on marital stress, 76% on cognitive flexibility, and 79% on self-value in the intervention group. A test power of 0.95 indicates that the sample size was adequate. Therefore, the research hypotheses are confirmed, and it can be stated that CFT had a significant impact on marital stress, cognitive flexibility, and self-worth in female healthcare workers.

Discussion

The purpose of this research was to evaluate the effectiveness of CFT on improving self-value, cognitive flexibility, and reducing marital stress in female healthcare workers in Iran. Considering the sensitive and stressful nature of their roles, reducing their work-related stress is crucial for maintaining their mental health and improving their quality of life.

The results indicated that CFT significantly reduced their marital stress. CFT is a psychotherapeutic approach that emphasizes compassion and kindness towards oneself and others. This method encourages increased self-awareness and self-acceptance while minimizing self-criticism and stress. The increased self-awareness allows individuals to confront stress more effectively. By fostering compassion, this therapy helps individuals experience less self-criticism and judgment and better manage marital relationships and life pressures, which eventually can reduce marital stress. These findings are consistent with those of Mehrabi et al. [31] on the effectiveness of group CFT on body image and interpersonal stress in women with breast cancer, and Pol et al. [32], examining the impact of CFT on self-criticism in patients with personality disorders. Moeeni et al. [33] found that CFT improved symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder in war veterans, which further supports the positive effects of CFT in managing stress.

The study also showed the positive impact of CFT on cognitive flexibility in female healthcare workers. Women with stress, anxiety, and despair may struggle with negative emotional reactions. CFT can help them develop the ability to handle these emotions and adopt a more adaptive and flexible mindset towards future challenges.

This approach encourages a shift from maladaptive responses to more constructive ways of thinking, fostering resilience and better coping strategies. This finding is consistent with the results of Vrabel et al., who compared cognitive behavioral therapy and CFT for adult patients with eating disorders and childhood trauma [34], and the results of Vidal and Soldevilla, who studied the effect of CFT on self-criticism and self-soothing [19]. Additionally, Navab et al.’s study on mothers of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder [20] suggested that CFT enhances psychological flexibility. CFT includes training on accepting failure and dealing with uncontrollable situations, which helps individuals learn from setbacks and approach life challenges with resilience.

This training encourages individuals to embrace both positive and negative emotions, fostering motivation and determination rather than succumbing to distress. As a result, women, particularly in high-pressure environments like medical settings, can develop greater cognitive flexibility and more effectively manage personal and professional challenges.

The findings also revealed that CFT significantly enhanced the self-worth of female healthcare workers. Compassion, as a human trait, involves attention, care, and respect toward oneself and others, fostering positive impacts on life. Compassion improves interpersonal relationships, leads to greater happiness and satisfaction, boosts self-confidence, and enhances one’s sense of contribution to society. The results are consistent with the results of Johannsen et al. [35] for the effect of group-based CFT on prolonged grief symptoms in adults, and the results of Craig et al. [36] for the effectiveness and acceptability of CFT in clinical populations. CFT enhances self-worth by improving relationships and increasing satisfaction with life. It strengthens individuals’ sense of power and efficacy, which boosts self-confidence. CFT also enhances one’s moral and social values. By promoting a feeling of connectedness to others, CFT helps individuals feel more cohesive within their communities, ultimately supporting their self-worth.

Conclusion

The CFT has positive effects on reducing marital stress, improving cognitive flexibility, and increasing self-worth in female healthcare workers. These results highlight the effectiveness of CFT as a psychological intervention for healthcare workers.

Limitations

This study had some limitations/disadvantages. The sample size was relatively small and limited to female healthcare workers from one hospital, which may affect the generalizability of the findings to all healthcare workers in Iran. Additionally, the study was conducted for a short period, and the long-term effects of CFT were not assessed. Future research can benefit from a larger sample size and a longitudinal design to examine the sustained impact of CFT. Furthermore, external factors such as social support or workplace environment were not explored, which may have influenced the outcomes. Finally, the study used self-report tools, which can lead to bias in responses due to participants’ subjective interpretations.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Islamic Azad University, Science and Research Branch, Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.IAU.SRB.REC.1403.128). All participants declared their informed consent to participate in the study.

Funding

The paper was extracted from the master thesis of Lida Memarpour, approved by the Department of Education and Counseling, Faculty of Literature, Humanities and Social Sciences, Science and Research Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization: Lida Memarpour and Nooshin Pordelan; Methodology, data analysis, and writing the original draft: Lida Memarpou; Data collection and literature review: Sedigheh Borna; Review and editing: Nooshin Pordelan and Sedigheh Borna; Supervision: Nooshin Pordelan.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all participants for their cooperation.

References

Studies have shown that work is a significant source of stress [1], and this stress is even greater in occupations related to healthcare workers [2]. Stress is a natural feeling and physiological response to internal or external stressors. Due to work-related stress, individuals become irritable, experience high levels of anxiety, and face increased emotional tension, cognitive processes, and changes in physical conditions. Work-related stress is thus defined as a response to a situation in the workplace that negatively affects employees, disrupts their lives, and causes physiological and psychological changes in them [3]. Healthcare workers face various work-related stressors that may affect their different aspects of lives [4]. Healthcare workers face life-threatening hazards and diseases associated with excessive work. Demanding work schedules, administrative correspondence, handling complex and sometimes malfunctioning tools, power hierarchies, expectations, and patient mortality cause them to experience high levels of stress in both workplace and personal life [5]. Healthcare-related jobs can affect marital stress [6]. Marital stress depends on several factors, including communication with a partner, receiving love, spousal support, religiosity, and marital satisfaction [7]. Marital satisfaction is influenced by stress [8, 9], and there is a positive relationship between stress and marital satisfaction [10].

The self-worth theory explains that an individual’s primary priority in life is to achieve self-acceptance, which is often attained through success. Self-worth is a self-evaluation construct that reflects an individual’s overall assessment of their value as a human being [11]. Brown argues that self-worth is not a decision, but an emotion based on feelings of self-compassion, not on ruthless scrutiny of what is not [12]. Cognitive flexibility is a key psychological concept explored in various fields. It refers to the capacity to adapt effectively to new conditions and changing situations. Studies have found a strong connection between cognitive flexibility and self-regulated learning, which involves the ability to control and manage one’s thoughts, emotions, and behaviors in pursuit of specific goals [13].

One therapeutic approach that can be applied to reduce work-related stress is compassion-focused therapy (CFT) [14]. Self-compassion can be considered a skill that can be learned [15]. The CFT believes that the positive attributes of compassion observed in the external world, which bring comfort and tranquility to individuals, should be internalized so that they can calmly manage their inner experiences and better deal with external challenges [16]. In this therapy, individuals learn not to escape from or suppress their undesirable feelings, which plays a crucial role in reducing negative thoughts [17]. The use of CFT has been extensively studied in psychology, and its effectiveness has been examined by various studies, which reported positive outcomes of this therapeutic approach [18, 19]. For example, Navab et al. [20] in a study found that CFT reduced psychological symptoms in Iranian mothers of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Vidal and Soldevilla [19] in a meta-analysis study reported that CFT reduced self-criticism and self-soothing. In this regard and given the important role of healthcare workers, the present study aimed to investigate whether CFT has a significant impact on self-worth, cognitive flexibility, and reduction of marital stress in Iranian female healthcare workers.

Materials and Methods

This is a quasi-experimental study with a pre-test/post-test design. The study population comprised all staff of Imam Khomeini Hospital in Tehran, Iran. Based on the recommendations that at least 15 participants per group are needed for experimental studies [21], a total sample size of 30 individuals was determined. Participants were selected using a voluntary sampling method and randomly assigned to two equal groups: Intervention (n=15) and control (n=15). The inclusion criteria were being female, being a healthcare worker, having at least one year of work experience, and willingness to participate in the study. Participants were excluded if they showed a lack of interest in continuing participation, provided incomplete responses to the questionnaires, or were absent from more than two sessions. To ensure ethical considerations, the purpose of the study was explained to all participants, and they were assured that their personal information would remain confidential and would only be used for research purposes. They could leave the study at any time.

The intervention was provided based on Gilbert’s CFT protocol [22, 23], which emphasizes developing self-compassion, reducing self-criticism, and enhancing emotional regulation through structured therapeutic techniques. The program was delivered at eight weekly sessions, each with specific objectives such as introducing CFT concepts, addressing self-blame and shame, fostering empathy, creating a safe emotional space, and building strategies for coping and self-care. A detailed summary of the sessions is presented in Table 1.

In this study, three questionnaires were used for data collection. A demographic form was used to survey age, marital status, and work experience. The contingencies of self-worth scale (CSWS), developed by Crocker et al. [24], was used to assess self-worth. It has 35 items rated on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), and seven subscales: Family support, competition, physical appearance, God’s love, academics, virtue, and approval from others. In this questionnaire, items 4, 6, 10, 13, 15, 23, and 30 have reversed scoring.

The total score ranges from 35 to 245, with higher scores indicating higher self-worth. The Persian version of this questionnaire was validated by Zaki [25], with a Cronbach’s α of 0.70 for male high school students and 0.83 for female high school students. In this study, self-worth refers to the total score of Persian CSWS. The cognitive flexibility inventory (CFI), developed by Dennis and Vander Wal [26], was also used in this study. It is a short self-report tool with 20 items used to measure a type of cognitive flexibility necessary for individual success in challenging negative thoughts and replacing them with positive ones. The items are scored on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 7 (completely agree).

It has a concurrent validity of -0.39 with the Beck depression inventory and a convergent validity of 0.75 with Martin and Rubin’s cognitive flexibility scale. For the Persian version, a test re-test reliability of 0.71 and a Cronbach’s α value of 0.90 for the entire scale have been reported [27, 28]. The Stockholm marital stress scale (SMSS), developed by Orth-Gomér et al. [29], was used to measure marital stress. It consists of 17 items scored by 0 or 1, with higher scores indicating higher marital stress. It has a Cronbach’s α value of 0.77 and satisfactory construct validity. The Persian version of this scale was validated by Noroozi et al. [30]. After collecting data before and after the intervention, they were analyzed using descriptive and inferential tests in SPSS software, version 26.

The variables were described using central tendency and dispersion indices. The analysis was done using the analysis of covariance. To assess the normality of the data distribution, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests were used. Since P>0.05 in both tests, the assumption of normality was accepted. The homogeneity of variances between the groups was also assessed using Levene’s test. Since the results were not significant (P>0.05), the assumption of homogeneity of variances was confirmed.

Results

The mean age of the participants was 32.45±5.80 years, and their average work experience was 8.75±4.20 years. In terms of marital status, 65% were married and 35% were single. Table 2 presents the mean scores of the study variables for each group at the pre-test and post-test phases. As shown in the table, the mean values of pre-test scores for each variable were similar between the two groups in the pre-test phase (P>0.05), while significant differences between the two groups were observed in the post-test phase (P<0.05). Therefore, it can be stated that the mean values of the research variables showed differences in the post-test.

To examine the statistical significance of this difference, the analysis of covariance test was used. The results are presented in Table 3. As shown in the table, considering the pre-test as a covariate, there was a significant difference (P<0.05). The CFT had an effect size of 78% on marital stress, 76% on cognitive flexibility, and 79% on self-value in the intervention group. A test power of 0.95 indicates that the sample size was adequate. Therefore, the research hypotheses are confirmed, and it can be stated that CFT had a significant impact on marital stress, cognitive flexibility, and self-worth in female healthcare workers.

Discussion

The purpose of this research was to evaluate the effectiveness of CFT on improving self-value, cognitive flexibility, and reducing marital stress in female healthcare workers in Iran. Considering the sensitive and stressful nature of their roles, reducing their work-related stress is crucial for maintaining their mental health and improving their quality of life.

The results indicated that CFT significantly reduced their marital stress. CFT is a psychotherapeutic approach that emphasizes compassion and kindness towards oneself and others. This method encourages increased self-awareness and self-acceptance while minimizing self-criticism and stress. The increased self-awareness allows individuals to confront stress more effectively. By fostering compassion, this therapy helps individuals experience less self-criticism and judgment and better manage marital relationships and life pressures, which eventually can reduce marital stress. These findings are consistent with those of Mehrabi et al. [31] on the effectiveness of group CFT on body image and interpersonal stress in women with breast cancer, and Pol et al. [32], examining the impact of CFT on self-criticism in patients with personality disorders. Moeeni et al. [33] found that CFT improved symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder in war veterans, which further supports the positive effects of CFT in managing stress.

The study also showed the positive impact of CFT on cognitive flexibility in female healthcare workers. Women with stress, anxiety, and despair may struggle with negative emotional reactions. CFT can help them develop the ability to handle these emotions and adopt a more adaptive and flexible mindset towards future challenges.

This approach encourages a shift from maladaptive responses to more constructive ways of thinking, fostering resilience and better coping strategies. This finding is consistent with the results of Vrabel et al., who compared cognitive behavioral therapy and CFT for adult patients with eating disorders and childhood trauma [34], and the results of Vidal and Soldevilla, who studied the effect of CFT on self-criticism and self-soothing [19]. Additionally, Navab et al.’s study on mothers of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder [20] suggested that CFT enhances psychological flexibility. CFT includes training on accepting failure and dealing with uncontrollable situations, which helps individuals learn from setbacks and approach life challenges with resilience.

This training encourages individuals to embrace both positive and negative emotions, fostering motivation and determination rather than succumbing to distress. As a result, women, particularly in high-pressure environments like medical settings, can develop greater cognitive flexibility and more effectively manage personal and professional challenges.

The findings also revealed that CFT significantly enhanced the self-worth of female healthcare workers. Compassion, as a human trait, involves attention, care, and respect toward oneself and others, fostering positive impacts on life. Compassion improves interpersonal relationships, leads to greater happiness and satisfaction, boosts self-confidence, and enhances one’s sense of contribution to society. The results are consistent with the results of Johannsen et al. [35] for the effect of group-based CFT on prolonged grief symptoms in adults, and the results of Craig et al. [36] for the effectiveness and acceptability of CFT in clinical populations. CFT enhances self-worth by improving relationships and increasing satisfaction with life. It strengthens individuals’ sense of power and efficacy, which boosts self-confidence. CFT also enhances one’s moral and social values. By promoting a feeling of connectedness to others, CFT helps individuals feel more cohesive within their communities, ultimately supporting their self-worth.

Conclusion

The CFT has positive effects on reducing marital stress, improving cognitive flexibility, and increasing self-worth in female healthcare workers. These results highlight the effectiveness of CFT as a psychological intervention for healthcare workers.

Limitations

This study had some limitations/disadvantages. The sample size was relatively small and limited to female healthcare workers from one hospital, which may affect the generalizability of the findings to all healthcare workers in Iran. Additionally, the study was conducted for a short period, and the long-term effects of CFT were not assessed. Future research can benefit from a larger sample size and a longitudinal design to examine the sustained impact of CFT. Furthermore, external factors such as social support or workplace environment were not explored, which may have influenced the outcomes. Finally, the study used self-report tools, which can lead to bias in responses due to participants’ subjective interpretations.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Islamic Azad University, Science and Research Branch, Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.IAU.SRB.REC.1403.128). All participants declared their informed consent to participate in the study.

Funding

The paper was extracted from the master thesis of Lida Memarpour, approved by the Department of Education and Counseling, Faculty of Literature, Humanities and Social Sciences, Science and Research Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization: Lida Memarpour and Nooshin Pordelan; Methodology, data analysis, and writing the original draft: Lida Memarpou; Data collection and literature review: Sedigheh Borna; Review and editing: Nooshin Pordelan and Sedigheh Borna; Supervision: Nooshin Pordelan.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all participants for their cooperation.

References

- Odes R, Hong O. Job stress and sleep disturbances among career firefighters in Northern California. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2023; 65(8):706-10. [DOI:10.1097/JOM.0000000000002901]

- Baraka AAE, Ramadan FH, Hassan EA. Predictors of critical care nurses' stress, anxiety, and depression in response to COVID-19 pandemic. Nursing in Critical Care. 2023; 28(2):177-83. [DOI:10.1111/nicc.12708] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Ramlawati R, Trisnawati E, Andriani Yasin N, Kurniawaty K. External alternatives, job stress on job satisfaction and employee turnover intention. Management Science Letters. 2021; 11(2):511-8. [DOI:10.5267/j.msl.2020.9.016]

- Hajiseyedrezaei SR, Alaee N, Zayeri F. Coping strategies with job stress of nurses working in intensive care units. Journal of Critical Care Nursing. 2018; 13(2):4-13. [Link]

- Jafari A, Amiri Majd M, Esfandiary Z. [Relationship between personality characteristics and coping strategies with job stress in nurses (Persian)]. Quarterly Journal of Nursing Management. 2013; 1(4):36-44. [Link]

- Olatubi MI, Olayinka O, Oyediran OO, Ademuyiwa GO, Dosunmu TO. Perceived stress, sexual and marital satisfaction among married healthcare workers in Nigeria. Nurse Media Journal of Nursing. 2022; 12(3):367-79. [DOI:10.14710/nmjn.v12i3.48477]

- Malm EK, Oti-Boadi M, Adom-Boakye NA, Andah A. Marital satisfaction and dissatisfaction among Ghanaians. Journal of Family Issues. 2023; 44(12):3117-41. [DOI:10.1177/0192513X221126752]

- Mashoufi M, Sarafraz N, Shadman A, Abedi S, Mardi A. [Relationship between health literacy and marital and sexual satisfaction and some demographic factors in women referring to health centers in Ardabil in 2019 (Persian)]. Journal of Health 2022; 13(1):49-59. [DOI:10.52547/j.health.13.1.49]

- Renanita T, Lukito Setiawan J. Marital satisfaction in terms of communication, conflict resolution, sexual intimacy, and financial relations among working and non-working wives. Makara Hubs-Asia. 2018; 22(1):12-21. [DOI:10.7454/hubs.asia.1190318]

- Shi Y, Whisman MA. Marital satisfaction as a potential moderator of the association between stress and depression. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2023; 327:155-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2023.01.093] [PMID]

- Chen G. Evaluating the core: Critical assessment of core self‐evaluations theory. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2012; 33(2):153-60. [DOI:10.1002/job.761]

- Brown JD. Self-esteem and self-evaluation: Feeling is believing. In: Suls J, editor. Psychological Perspectives on the Self, Volume 4. New York: Psychology Press; 2014. [DOI:10.2478/atd-2023-0006]

- Dağgöl GD. Online self-regulated learning and cognitive flexibility through the eyes of English-major students. Acta Educ Generalis. 2023; 13(1):107-32. [DOI:10.2478/atd-2023-0006]

- Han A, Kim TH. Effects of self-compassion interventions on reducing depressive symptoms, anxiety, and stress: A meta-analysis. Mindfulness. 2023; 1-29. [DOI:10.1007/s12671-023-02148-x] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Cai RY, Edwards C, Love AM, Brown L, Gibbs V. Self-compassion improves emotion regulation and mental health outcomes: A pilot study of an online self-compassion program for autistic adults. Autism. 2024; 28(10):2572-85. [DOI:10.1177/13623613241235061] [PMID]

- Taher Pour M, Sohrabi A, Zemestani M. [Effectiveness of compassion-focused therapy on depression, anxiety, stress, and weight self-efficacy in patients with eating disorder (Persian)]. Journal of Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences. 2019; 26(4):505-13. [Link]

- Lucre K, Clapton N. The Compassionate Kitbag: A creative and integrative approach to compassion-focused therapy. Psychology and Psychotherapy. 2021; 94(Suppl 2):497-516. [DOI:10.1111/papt.12291] [PMID]

- Millard LA, Wan MW, Smith DM, Wittkowski A. The effectiveness of compassion focused therapy with clinical populations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2023; 326:168-92. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2023.01.010] [PMID]

- Vidal J, Soldevilla JM. Effect of compassion‐focused therapy on self‐criticism and self‐soothing: A meta‐analysis. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2023; 62(1):70-81. [DOI:10.1111/bjc.12394] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Navab M, Dehghani A, Salehi M. Effect of compassion‐focused group therapy on psychological symptoms in mothers of attention‐deficit hyperactivity disorder children: A pilot study. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research. 2019; 19(2):149-57. [DOI:10.1002/capr.12212]

- Pordelan N, Sadeghi A, Abedi MR, Kaedi M. Promoting student career decision-making self-efficacy: An online intervention. Education and Information Technologies. 2020; 25(2):985-96. [DOI:10.1007/s10639-019-10003-7]

- Gilbert P. Compassion focused therapy: Distinctive features. London: Routledge; 2010. [DOI:10.4324/9780203851197]

- Gilbert P. The origins and nature of compassion focused therapy. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2014; 53(1):6-41. [DOI:10.1111/bjc.12043] [PMID]

- Crocker J, Luhtanen RK, Cooper ML, Bouvrette A. Contingencies of self-worth in college students: Theory and measurement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003; 85(5):894-908. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.85.5.894] [PMID]

- Zaki M. Psychometric properties of the self-worth scale (CSWS) for high school student in Esfahan. Psychological Models and Methods. 2012; 2(7):87-98. [Link]

- Dennis JP, Vander Wal JS. The cognitive flexibility inventory: Instrument development and estimates of reliability and validity. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2010; 34:241-53. [DOI:10.1007/s10608-009-9276-4]

- Soltani E, Shareh H, Bahrainian SA, Farmani A. [The mediating role of cognitive flexibility in correlation of coping styles and resilience with depression (Persian)]. Pajoohandeh Journal. 2013; 18(2):88-96. [Link]

- Sharifi P, Mousavi SA, Dehghan M. The effect of stress induction on failure and working memory: The role of cognitive flexibility. Quarterly Journal of Evolutionary Psychology. 2018; 15(58):153-64. [DOI:10.22051/PSY.2023.40227.2613]

- Orth-Gomér K, Wamala SP, Horsten M, Schenck-Gustafsson K, Schneiderman N, Mittleman MA. Marital stress worsens prognosis in women with coronary heart disease: The stockholm female coronary risk study. JAMA. 2000; 284(23):3008-14. [DOI:10.1001/jama.284.23.3008] [PMID]

- Noroozi S, Nazari A, Rasouli M, Davarnia R, Babaeigharmkhani M. [Effect of brief self-regulation couple therapy (SRCT) on reducing the couples’ marital stress (Persian)]. Internal Medicine Today. 2015; 21(1):1-6. [DOI:10.18869/acadpub.hms.21.1.1]

- Mehrabi N, Amiri H, Omidi A, Sarvizadeh M. The effectiveness of group compassion-focused therapy on body image and interpersonal stress among women with breast cancer: A randomized controlled trial. IJ Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 18(1):e139764. [DOI:10.5812/ijpbs-139764]

- Pol SM, de Jong A, Trompetter H, Bohlmeijer ET, Chakhssi F. Effectiveness of compassion-focused therapy for self-criticism in patients with personality disorders: A multiple baseline case series study. Personality and Mental Health. 2024; 18(1):69-79. [DOI:10.1002/pmh.1597] [PMID]

- Moeeni F, Taheri N, Goodarzi N, Dabaghi P, Rahnejat A, Donyavi V. [Effectiveness of compassion therapy on symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (Persian)]. Nurse and physician within war 2020; 7(23):20-5. [Link]

- Vrabel KR, Waller G, Goss K, Wampold B, Kopland M, Hoffart A. Cognitive behavioral therapy versus compassion focused therapy for adult patients with eating disorders with and without childhood trauma: A randomized controlled trial in an intensive treatment setting. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2024; 174:104480. [DOI:10.1016/j.brat.2024.104480] [PMID]

- Johannsen M, Schlander C, Farver-Vestergaard I, Lundorff M, Wellnitz KB, Komischke-Konnerup KB, et al. Group-based compassion-focused therapy for prolonged grief symptoms in adults - Results from a randomized controlled trial. Psychiatry Research. 2022; 314:114683. [DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114683] [PMID]

- Craig C, Hiskey S, Spector A. Compassion focused therapy: A systematic review of its effectiveness and acceptability in clinical populations. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 2020; 20(4):385-400. [DOI:10.1080/14737175.2020.1746184] [PMID]

Type of Study: Original Article |

Subject:

Health Education

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |