Volume 13, Issue 4 (Autumn 2025)

Iran J Health Sci 2025, 13(4): 267-274 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: 14020239

Clinical trials code: 1492342

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Darvishi M, Valipour Dehnou V, Eslami R, Nazari Pirdoustia S, Nabavinik H. Effects of Six Weeks of two type of Interval Training on AnthropometricMeasures and Functional Capacity in Overweight/Obese Adolescent Boys: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Iran J Health Sci 2025; 13 (4) :267-274

URL: http://jhs.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-1021-en.html

URL: http://jhs.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-1021-en.html

Mahmoud Darvishi

, Vahid Valipour Dehnou *

, Vahid Valipour Dehnou *

, Rasoul Eslami

, Rasoul Eslami

, Sirous Nazari Pirdoustia

, Sirous Nazari Pirdoustia

, Hossein Nabavinik

, Hossein Nabavinik

, Vahid Valipour Dehnou *

, Vahid Valipour Dehnou *

, Rasoul Eslami

, Rasoul Eslami

, Sirous Nazari Pirdoustia

, Sirous Nazari Pirdoustia

, Hossein Nabavinik

, Hossein Nabavinik

Department of Sports Sciences, Faculty of Literature and Human Sciences, Lorestan University, Khorramabad, Iran. , valipour.v@lu.ac.ir

Full-Text [PDF 735 kb]

(13 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (408 Views)

Full-Text: (6 Views)

Introduction

Obesity and overweight have been shown to have physiological consequences, such as an increased risk of cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, cancer, hypertension, and dyslipidemia [1-4], as well as psychological effects, including the onset of mental health issues, like insomnia, depression, decreased self-esteem, and anxiety [5]. Additionally, obesity can impact physical parameters, such as motor performance motor coordination, and increase the risk of injuries, as these parameters are directly related to regular physical activity and body composition in children and adolescents [6, 7]. Zhu et al. indicated that overweight or obese children exhibit poorer general motor coordination in weight-bearing tasks and tend to be less active compared to their normal-weight peers. They also have weaker motor skills, such as jumping, running, and balance compared to normal-weight children [8].

Physical activity is a crucial factor in reducing overweight and obesity, serving as one of the most beneficial tools for the prevention and treatment of obesity and its related consequences [9]. While most training guidelines recommended for weight loss focus on continuous exercise, the uniformity of this method appears to be a barrier to breaking inactive lifestyles. Therefore, alternative training methods, such as interval training have shown better results than continuous exercise in obese individuals [10]. Moreover, some more favorable changes, such as improved maximal oxygen uptake, blood glucose levels, insulin resistance index, insulin levels, hemoglobin A1c, body mass, and body mass index (BMI), can be achieved through this training approach in obese patients [10, 11].

High-intensity interval training (HIIT), which is also referred to as HIIT-R, due to its design being based on running exercises, is increasingly considered an effective and time-efficient strategy for enhancing endurance performance [12]. HIIT is widely used in athletic populations to enhance the efficiency of various energy systems and improve overall athletic performance [13, 14]. Generally, HIIT-R is defined as repeated periods of high-intensity exercise performed at or near maximal intensity, typically above 80% of the maximal heart rate. Many HIIT-R protocols are classified as “low volume,” lasting less than or equal to 30 minutes per session [15]. In contrast, high-intensity functional training (HIFT) utilizes various training methods, including mono-structural aerobic activities (running and rowing), bodyweight movements (squats, push-ups, etc.), and subsets of weightlifting exercises (snatches, deadlifts, and shoulder presses) [16]. Unlike HIIT-R, which tends to focus on single training methods (such as running), HIFT emphasizes functional, multi-joint movements, affecting both aerobic and anaerobic energy pathways, and can be adapted to any fitness level. Through aerobic and resistance training, HIFT engages more muscle groups [17-20] and may positively affect blood glucose levels in individuals with type 2 diabetes [21, 22].

Research has evaluated the effects of HIFT on numerous health indicators. For example, Feito et al. reported a significant reduction in body fat percent (6.5%) after 16 weeks of HIFT among a group of healthy adults [17]. Heinrich et al. found that HIFT is an effective strategy for maintaining adherence to and enjoyment of physical activity among inactive adults [23]. Overall, HIFT appears to be a potentially useful strategy for reducing obesity and potentially mitigating the spread of type 2 diabetes [20].

Considering the importance of weight loss in overweight and obese individuals, the choice of training method is crucial, as it not only affects weight loss but also influences the participation rate of adolescents in physical activities. Given that HIFT is a practical and suitable training method for overweight and obese adolescents, it appears that this type of training, with its high variety of movements, may have a greater impact on the mentioned variables in overweight and obese adolescents. Moreover, research comparing HIFT and HIIT-R, particularly in younger age groups, is very limited. The aim of the present study was to investigate and compare the effects of six weeks of HIFT and HIIT-R protocols on anthropometric measures and functional capacity in overweight/obese adolescents.

Materials and Methods

Participants

In this randomized controlled trial, 30 overweight and obese adolescents aged 13 to 15 years, classified based on the World Health Organization (WHO)’s BMI criteria, voluntarily participated. Considering the researcher’s position and in order to have more control over the study process, Shahid Beheshti School in Khorramabad was selected as the statistical population. The sample size was determined using G*Power software, version 3.1.9 (Heinrich Heine University, Düsseldorf, Germany) for repeated measures ANOVA with an effect size of 0.28, alpha=0.05, and power=0.80. Participants were randomly assigned to three equal groups: Control, HIIT-R, and HIFT. In this study, the number of samples, exercise training protocol, and study duration were different from those in other studies. In addition, despite the presence of a control group, the selection of samples and their assignment to each group was done randomly by a non-researcher. After being informed about the study procedures, the participants signed written consent forms.

Inclusion criteria included being aged 13 to 15 years, having a BMI over 25, being in good physical health with no musculoskeletal issues, no history of fractures, and no traumatic or orthopedic problems. Additionally, participants had not engaged in any regular physical exercise for two months before the start of the training protocol. The health status of participants was verified through self-reported medical history and a brief physical examination conducted by a qualified researcher.

Measurements

Physical fitness assessment

Agility: The agility t-test was used to measure the agility of the subjects. Three cones were placed five meters apart in a straight line, with a fourth cone positioned ten meters away from the middle cone, forming a “T” shape. The athlete began at the cone at the base of the “T” and sprinted to the middle cone, touching it. Then, the athlete ran five meters to the left cone and touched it. Next, the athlete ran ten meters to the right cone and touched it. The athlete then shuffled five meters back to the middle cone and touched it before finally sprinting ten meters backward to the starting cone. The time was recorded as soon as the athlete touched the starting cone [24].

Maximum aerobic capacity: The Cooper VO2max test was used to measure the maximum aerobic capacity of the subjects. In this test, athletes are required to cover a distance of 2.4 km (6 laps of a 400-meter track) at their maximum possible speed, and their time record is recorded. Based on published equations, the aerobic capacity of athletes is then calculated [24].

Functional assessment

Functional movement screen (FMS): FMS, as one of the most popular screening systems in the field of sports physiotherapy, consists of seven tests focusing on different areas of the musculoskeletal system. It systematically identifies movement restrictions or weaknesses [25]. The seven tests include deep squat, hurdle step, in-line lunge, shoulder mobility, active straight leg raise, trunk stability push-up, and rotary stability [26]. Scoring in this screening is done on a scale from zero to three for each test, ranging from pain occurrence to full execution [25].

Anthropometric measurement

Anthropometric measurements, including waist circumference, hip circumference, height, weight, and BMI were taken according to the international standards for anthropometric assessment [27].

Training protocol

HIIT-R group

Participants in the HIIT-R group completed four sets of four-minute running sessions at 90 to 95% of their maximum heart rate, followed by three minutes of active recovery at 60 to 70% of their maximum heart rate [28] for six weeks.

HIFT group

In the HIFT group, participants underwent HIFT training, consisting of six stations: Elliptical, battle rope, agility ladder drills, kettlebell swings, burpees, and multi-jumps with hurdle training. Each station involved 30 seconds of high-intensity training, followed by a 15-second rest period between stations. A 3-minute rest interval was given between each set [29]. Participants in the HIFT group followed the training protocol twice in the first two weeks, three times in the second two weeks, and four times in the third two weeks [29]. Both experimental groups performed their respective training under the supervision of the researcher for six weeks.

Statistical analysis

The number of participants was estimated by G*Power analysis software, version 3.1. Based on α=0.05, and a power (1−β) of 0.80, the sample size needed to detect significant changes in the blood factors between groups was at least 30 participants (n=10 for each group). The normality of data and homogeneity of variance were assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk and Leven’s tests, respectively. After achieving the pre-hypothesis, the repeated measures ANOVA test was used to examine between-group differences following the 6-week training program. Paired t-tests were employed to compare the changes in each group (pre-test to post-test). All analyses were performed using SPSS software, version 21. Statistical significance was accepted if P≤0.05.

Results

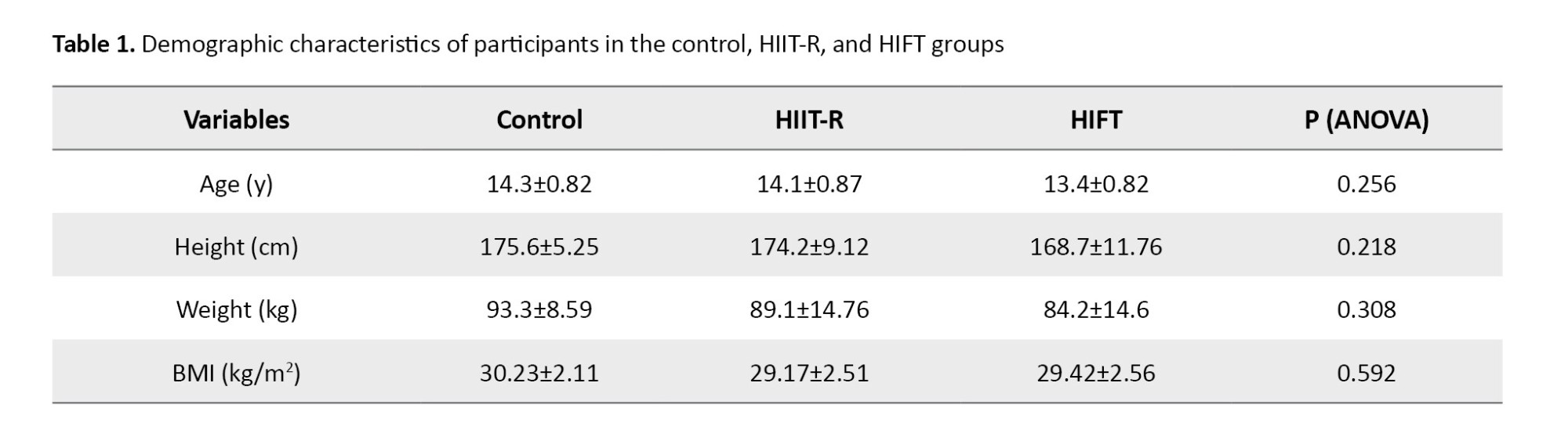

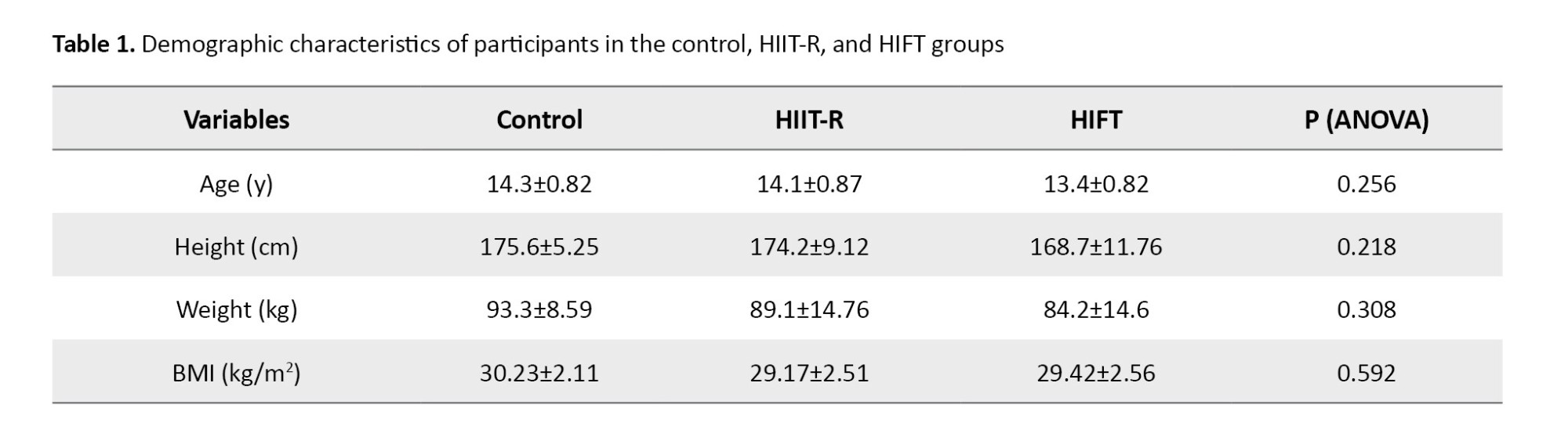

The demographic characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. There was no significant difference between the groups in age (P=0.256), height (P=0.218), weight (P=0.308) and BMI (P=0.592) at baseline.

Physical fitness variables

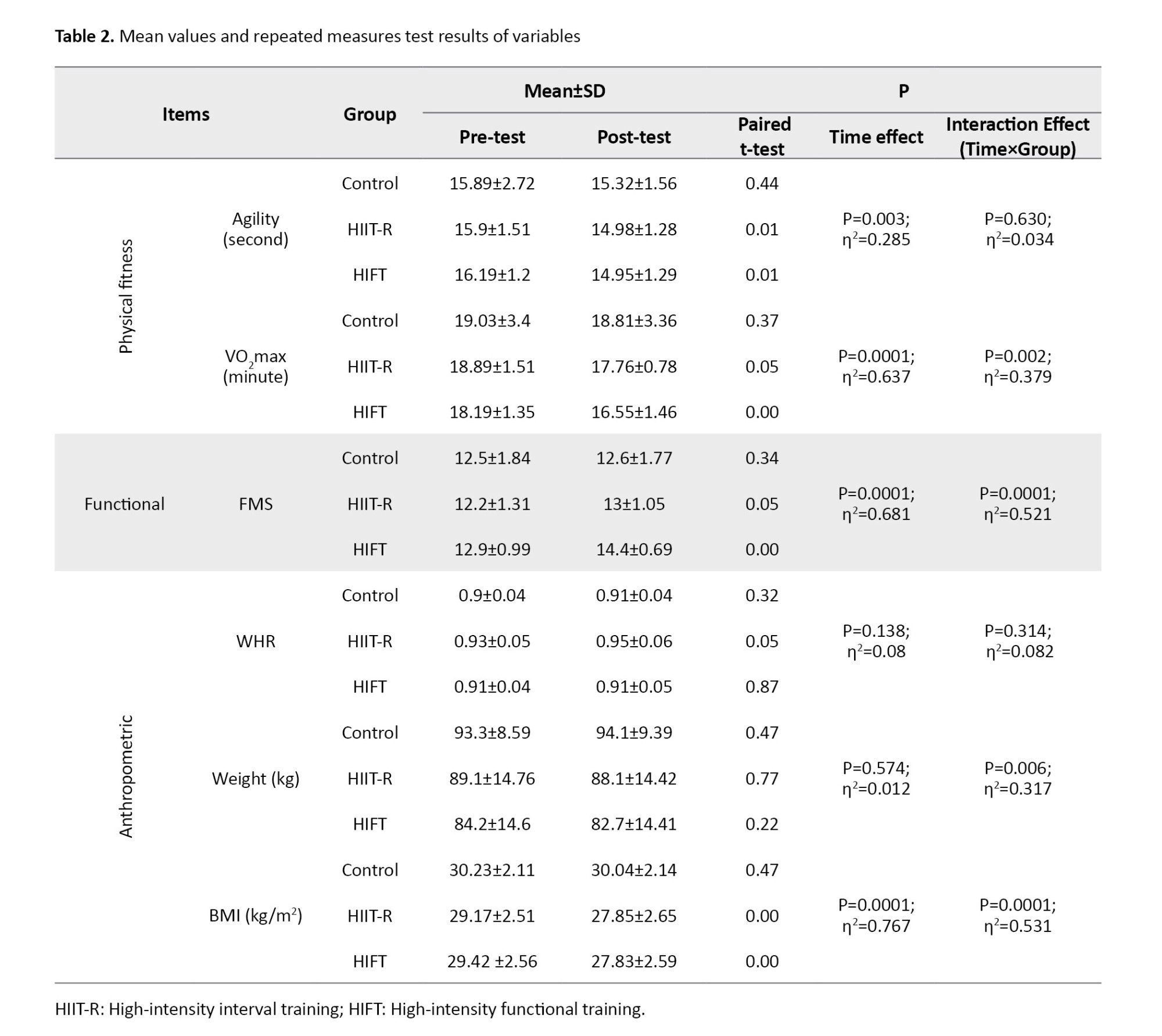

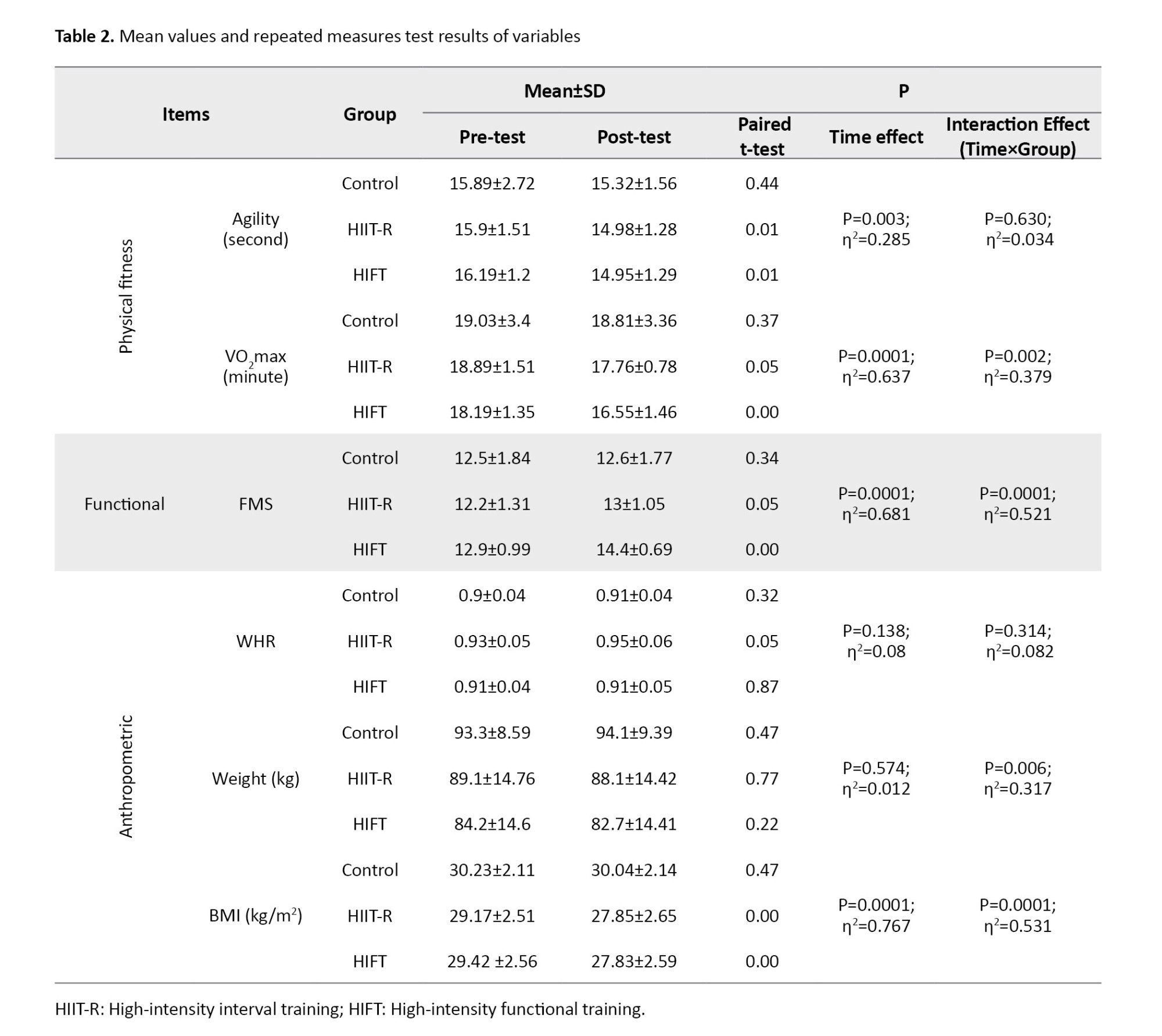

Repeated measurement test with 2-time levels (before and after training) and three groups (control, HIIT-R, and HIFT) was used for statistical evaluation. The effect of time was significant for agility (P=0.003). A pairwise comparison of the pre-test and post-test results for the groups indicated that both the HIIT-R and HIFT groups were able to reduce their agility values in the post-test compared to the pre-test (P<0.01 for both). However, both the group effect (P=0.966) and the time×group interaction effect (P=0.630) were not significant. These results show that, despite having a significant effect within the groups, these two types of training could not produce a significant effect on agility when compared to the control group.

The effect of time was significant for VO2max (P=0.0001). The pairwise comparison of the pre-test and post-test results for the groups indicated that both the HIIT-R and HIFT groups were able to reduce their VO2max results in the post-test compared to the pre-test (P<0.05 for HIIT-R; P<0.001 for HIFT). While there was no significant group effect (P=0.294), the time×group interaction effect was significant (P=0.002). Comparing these three groups shows that both types of HIFT and HIIT-R training, in comparison to the control group, were able to reduce the VO2max test results in the post-test, and HIFT training had a greater effect than HIIT-R training (Table 2).

Functional variable

The effect of time was significant for FMS (P=0.0001). A pairwise comparison of the pre-test and post-test results indicated that both the HIIT-R and HIFT groups were able to increase their FMS values in the post-test compared to the pre-test (P<0.05 for HIIT-R; P<0.001 for HIFT). While there was no significant group effect (P=0.127), the time×group interaction effect was significant (P=0.0001). Therefore, both HIFT and HIIT-R were able to improve FMS values in the post-test, and this improvement was greater in the HIFT group than in the HIIT-R group (Table 2).

Anthropometric measures

The results of the repeated measures test for weight showed that the effect of time was not significant (P=0.574). Also, there was no significant group effect (P=0.196). However, the time×group interaction effect was significant (P=0.006), which, when comparing these three groups, shows that HIFT training was able to reduce weight values in the post-test compared to the control group.

For BMI, the effect of time was significant (P=0.0001). A pairwise comparison of the pre-test and post-test results for the groups showed that both the HIIT-R and HIFT groups were able to reduce BMI compared to the pre-test (P<0.01 for all). While there was no significant group effect (P=0.263), the time×group interaction effect was significant (P=0.0001), which, when comparing these three groups, shows that both types of HIFT and HIIT-R training were able to reduce BMI values in the post-test compared to the control group (Table 2).

For WHR, both the time effect (P=0.138) and time×group interaction effect (P=0.314) were not significant. Therefore, the two training protocols did not affect this variable (Table 2).

Discussion

The results of the present study showed that both HIIT-R and HIFT protocols significantly impacted physical fitness indices (agility and VO2max); however, only the effect on VO2max was significant compared to the control group. Nevertheless, HIFT training had a greater impact on physical fitness indices compared to HIIT-R. Both training modalities were effective in improving functional performance and BMI. The HIFT protocol demonstrated a greater effect on functional and anthropometric indices than HIIT-R. Moreover, a significant difference in weight was observed only in the HIFT group compared to the control group.

HIIT-R is widely used, but despite its benefits, it may not always be practical due to limited facilities, low variety, and high difficulty, which can affect adherence [30]. Studies show that HIIT-R training effectively enhances aerobic and anaerobic capacity. For example, an eight-week HIIT-R program at 80% maximum heart rate, with a work-to-rest ratio of 0.8 (60 seconds of activity and 75 seconds of rest), and lasting 23 minutes per session, resulted in increased VO2max, significant reductions in BMI and diastolic blood pressure, and no change in fasting blood glucose levels [31]. Nourry et al. examined an eight-week HIIT-R program at 80% of maximum aerobic speed, with equal work-to-rest ratios, 10-20 seconds of rest, and 30 minutes per session. They found significant improvements in forced vital capacity, VO2max, and peak power, with no effect on maximum heart rate or body fat percentage [32]. Gamelin et al. studied a seven-week HIIT-R program at 100-190% maximal aerobic velocity (MAV), with work-to-rest ratios ranging from 0.3 to 1.5 (5-30 seconds of activity, 15-30 seconds of rest, for 30 minutes per session). They observed significant changes in body mass, VO2max, and MAV [33]. Bauer et al. emphasized the importance of improving cardiorespiratory fitness to reduce cardiovascular risk in children and adolescents [31, 34], as well as cardiometabolic risk in adolescents [35]. Compared to other forms of training, such as low to moderate-intensity running or walking, both in-school and out-of-school, HIIT-R led to greater improvements in cardiovascular indicators and biomarkers of cardiovascular diseases in children and adolescents [36]. Therefore, the positive effects of HIIT-R on physical fitness and body composition is well-documented, which is consistent with the findings of the present study.

In contrast, HIFT has gained great popularity, even among individuals with chronic conditions, due to its varied and functional nature and metabolic benefits [23, 37, 38]. The research comparing HIIT-R and HIFT protocols is limited, highlighting the importance of understanding the effectiveness of these two training methods. A review of the literature shows that both HIIT-R and HIFT, conducted for 12 weeks, positively impact body composition and aerobic fitness in female students (average age: 20.45 years, BMI: 22.15 kg/m2). HIIT-R involved 30 seconds of activity followed by 30 seconds of rest (1:1 ratio), while HIFT involved a 2:1 work-to-rest ratio. Both training types significantly improved VO2max and body fat percentage, with HIFT also enhancing muscular performance (sit-ups and jumps). Neither training type had a significant effect on the waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) or BMI [39]. Therefore, it is concluded that HIFT is as effective as HIIT-R in improving body composition and aerobic fitness, with additional benefits for muscular performance. Gavanda et al. investigated the effects of a six-week HIFT program compared to strength training and endurance training on strength and endurance performance in adolescents (average age: 17 years). The HIFT group showed significant improvements in all performance tests (countermovement jump (CMJ), 20-m sprint (20 m), 3-repetition maximum back squat (3RM), and Yo-Yo test), while the strength training (CMJ, 3RM, and Yo-Yo test) and endurance training (CMJ, 20 m, and Yo-Yo test) groups showed significant improvements in only three performance variables [40]. In a study focused on overweight individuals, Cao et al. compared the effects of HIIT-R and HIFT on body composition, cardiorespiratory fitness, and muscular fitness in young adults (average age: 22.34 years, BMI: 25.43 kg/m2). The 12-week program included 4 sets of 30 seconds of activity and rest, progressing from 100% of maximal aerobic speed (MAS) in weeks 1-4 to 120% of MAS in weeks 9-12. Both training modalities led to significant improvements in muscle strength (long jump, push-ups, handgrip strength, and back strength), cardiorespiratory fitness (20-meter shuttle run, MAS, and VO2max), and body composition (lean mass, body fat percentage, and visceral fat area). However, HIFT had a more substantial positive impact on muscular fitness, likely due to greater increases in lean mass [38].

Comparatively, HIFT’s greater impact on physical fitness variables (agility and VO2max) may be due to the improved muscle strength and endurance, as well as increased lean body mass, which HIIT-R lacks due to the absence of resistance training [38-41]. Also, HIFT’s benefits for VO2max have been previously documented [29]. For FMS, the similarity in movement patterns between HIFT training and the FMS test likely contributes to its effectiveness. Given the lack of impact of these training protocols on WHR and their minimal effect on weight, further studies are needed to understand the reasons behind their influence on BMI.

One of the main limitations of this study is the relatively small sample size, which may affect the statistical power and generalizability of the findings. Additionally, the absence of long-term follow-up prevents the evaluation of the sustainability of training effects. The lack of dietary control may have influenced anthropometric and functional outcomes. Future research should consider measuring lean body mass alongside body fat percentage in a laboratory setting, implementing dietary monitoring, and conducting long-term follow-ups. Moreover, clinical trials with larger and more diverse populations are recommended to strengthen the validity and applicability of the results.

Conclusion

The six-week HIFT training significantly enhanced physical fitness indices (agility and VO2max), FMS, and BMI in overweight and obese adolescents. Moreover, HIFT training can serve as a suitable alternative to HIIT-R workouts, demonstrating even greater effects on VO2max and potentially promoting muscle mass, strength, and endurance, thereby addressing key challenges faced by overweight and obese adolescents.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committee of the Physical Education and Sport Sciences Research Institute, Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.SSRC.REC.1404.044).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection and analysis, interpretation of the results, and drafting of the manuscript. Each author approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support of the participants, without whose active contributions, the study could not have been completed successfully.

References

Obesity and overweight have been shown to have physiological consequences, such as an increased risk of cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, cancer, hypertension, and dyslipidemia [1-4], as well as psychological effects, including the onset of mental health issues, like insomnia, depression, decreased self-esteem, and anxiety [5]. Additionally, obesity can impact physical parameters, such as motor performance motor coordination, and increase the risk of injuries, as these parameters are directly related to regular physical activity and body composition in children and adolescents [6, 7]. Zhu et al. indicated that overweight or obese children exhibit poorer general motor coordination in weight-bearing tasks and tend to be less active compared to their normal-weight peers. They also have weaker motor skills, such as jumping, running, and balance compared to normal-weight children [8].

Physical activity is a crucial factor in reducing overweight and obesity, serving as one of the most beneficial tools for the prevention and treatment of obesity and its related consequences [9]. While most training guidelines recommended for weight loss focus on continuous exercise, the uniformity of this method appears to be a barrier to breaking inactive lifestyles. Therefore, alternative training methods, such as interval training have shown better results than continuous exercise in obese individuals [10]. Moreover, some more favorable changes, such as improved maximal oxygen uptake, blood glucose levels, insulin resistance index, insulin levels, hemoglobin A1c, body mass, and body mass index (BMI), can be achieved through this training approach in obese patients [10, 11].

High-intensity interval training (HIIT), which is also referred to as HIIT-R, due to its design being based on running exercises, is increasingly considered an effective and time-efficient strategy for enhancing endurance performance [12]. HIIT is widely used in athletic populations to enhance the efficiency of various energy systems and improve overall athletic performance [13, 14]. Generally, HIIT-R is defined as repeated periods of high-intensity exercise performed at or near maximal intensity, typically above 80% of the maximal heart rate. Many HIIT-R protocols are classified as “low volume,” lasting less than or equal to 30 minutes per session [15]. In contrast, high-intensity functional training (HIFT) utilizes various training methods, including mono-structural aerobic activities (running and rowing), bodyweight movements (squats, push-ups, etc.), and subsets of weightlifting exercises (snatches, deadlifts, and shoulder presses) [16]. Unlike HIIT-R, which tends to focus on single training methods (such as running), HIFT emphasizes functional, multi-joint movements, affecting both aerobic and anaerobic energy pathways, and can be adapted to any fitness level. Through aerobic and resistance training, HIFT engages more muscle groups [17-20] and may positively affect blood glucose levels in individuals with type 2 diabetes [21, 22].

Research has evaluated the effects of HIFT on numerous health indicators. For example, Feito et al. reported a significant reduction in body fat percent (6.5%) after 16 weeks of HIFT among a group of healthy adults [17]. Heinrich et al. found that HIFT is an effective strategy for maintaining adherence to and enjoyment of physical activity among inactive adults [23]. Overall, HIFT appears to be a potentially useful strategy for reducing obesity and potentially mitigating the spread of type 2 diabetes [20].

Considering the importance of weight loss in overweight and obese individuals, the choice of training method is crucial, as it not only affects weight loss but also influences the participation rate of adolescents in physical activities. Given that HIFT is a practical and suitable training method for overweight and obese adolescents, it appears that this type of training, with its high variety of movements, may have a greater impact on the mentioned variables in overweight and obese adolescents. Moreover, research comparing HIFT and HIIT-R, particularly in younger age groups, is very limited. The aim of the present study was to investigate and compare the effects of six weeks of HIFT and HIIT-R protocols on anthropometric measures and functional capacity in overweight/obese adolescents.

Materials and Methods

Participants

In this randomized controlled trial, 30 overweight and obese adolescents aged 13 to 15 years, classified based on the World Health Organization (WHO)’s BMI criteria, voluntarily participated. Considering the researcher’s position and in order to have more control over the study process, Shahid Beheshti School in Khorramabad was selected as the statistical population. The sample size was determined using G*Power software, version 3.1.9 (Heinrich Heine University, Düsseldorf, Germany) for repeated measures ANOVA with an effect size of 0.28, alpha=0.05, and power=0.80. Participants were randomly assigned to three equal groups: Control, HIIT-R, and HIFT. In this study, the number of samples, exercise training protocol, and study duration were different from those in other studies. In addition, despite the presence of a control group, the selection of samples and their assignment to each group was done randomly by a non-researcher. After being informed about the study procedures, the participants signed written consent forms.

Inclusion criteria included being aged 13 to 15 years, having a BMI over 25, being in good physical health with no musculoskeletal issues, no history of fractures, and no traumatic or orthopedic problems. Additionally, participants had not engaged in any regular physical exercise for two months before the start of the training protocol. The health status of participants was verified through self-reported medical history and a brief physical examination conducted by a qualified researcher.

Measurements

Physical fitness assessment

Agility: The agility t-test was used to measure the agility of the subjects. Three cones were placed five meters apart in a straight line, with a fourth cone positioned ten meters away from the middle cone, forming a “T” shape. The athlete began at the cone at the base of the “T” and sprinted to the middle cone, touching it. Then, the athlete ran five meters to the left cone and touched it. Next, the athlete ran ten meters to the right cone and touched it. The athlete then shuffled five meters back to the middle cone and touched it before finally sprinting ten meters backward to the starting cone. The time was recorded as soon as the athlete touched the starting cone [24].

Maximum aerobic capacity: The Cooper VO2max test was used to measure the maximum aerobic capacity of the subjects. In this test, athletes are required to cover a distance of 2.4 km (6 laps of a 400-meter track) at their maximum possible speed, and their time record is recorded. Based on published equations, the aerobic capacity of athletes is then calculated [24].

Functional assessment

Functional movement screen (FMS): FMS, as one of the most popular screening systems in the field of sports physiotherapy, consists of seven tests focusing on different areas of the musculoskeletal system. It systematically identifies movement restrictions or weaknesses [25]. The seven tests include deep squat, hurdle step, in-line lunge, shoulder mobility, active straight leg raise, trunk stability push-up, and rotary stability [26]. Scoring in this screening is done on a scale from zero to three for each test, ranging from pain occurrence to full execution [25].

Anthropometric measurement

Anthropometric measurements, including waist circumference, hip circumference, height, weight, and BMI were taken according to the international standards for anthropometric assessment [27].

Training protocol

HIIT-R group

Participants in the HIIT-R group completed four sets of four-minute running sessions at 90 to 95% of their maximum heart rate, followed by three minutes of active recovery at 60 to 70% of their maximum heart rate [28] for six weeks.

HIFT group

In the HIFT group, participants underwent HIFT training, consisting of six stations: Elliptical, battle rope, agility ladder drills, kettlebell swings, burpees, and multi-jumps with hurdle training. Each station involved 30 seconds of high-intensity training, followed by a 15-second rest period between stations. A 3-minute rest interval was given between each set [29]. Participants in the HIFT group followed the training protocol twice in the first two weeks, three times in the second two weeks, and four times in the third two weeks [29]. Both experimental groups performed their respective training under the supervision of the researcher for six weeks.

Statistical analysis

The number of participants was estimated by G*Power analysis software, version 3.1. Based on α=0.05, and a power (1−β) of 0.80, the sample size needed to detect significant changes in the blood factors between groups was at least 30 participants (n=10 for each group). The normality of data and homogeneity of variance were assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk and Leven’s tests, respectively. After achieving the pre-hypothesis, the repeated measures ANOVA test was used to examine between-group differences following the 6-week training program. Paired t-tests were employed to compare the changes in each group (pre-test to post-test). All analyses were performed using SPSS software, version 21. Statistical significance was accepted if P≤0.05.

Results

The demographic characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. There was no significant difference between the groups in age (P=0.256), height (P=0.218), weight (P=0.308) and BMI (P=0.592) at baseline.

Physical fitness variables

Repeated measurement test with 2-time levels (before and after training) and three groups (control, HIIT-R, and HIFT) was used for statistical evaluation. The effect of time was significant for agility (P=0.003). A pairwise comparison of the pre-test and post-test results for the groups indicated that both the HIIT-R and HIFT groups were able to reduce their agility values in the post-test compared to the pre-test (P<0.01 for both). However, both the group effect (P=0.966) and the time×group interaction effect (P=0.630) were not significant. These results show that, despite having a significant effect within the groups, these two types of training could not produce a significant effect on agility when compared to the control group.

The effect of time was significant for VO2max (P=0.0001). The pairwise comparison of the pre-test and post-test results for the groups indicated that both the HIIT-R and HIFT groups were able to reduce their VO2max results in the post-test compared to the pre-test (P<0.05 for HIIT-R; P<0.001 for HIFT). While there was no significant group effect (P=0.294), the time×group interaction effect was significant (P=0.002). Comparing these three groups shows that both types of HIFT and HIIT-R training, in comparison to the control group, were able to reduce the VO2max test results in the post-test, and HIFT training had a greater effect than HIIT-R training (Table 2).

Functional variable

The effect of time was significant for FMS (P=0.0001). A pairwise comparison of the pre-test and post-test results indicated that both the HIIT-R and HIFT groups were able to increase their FMS values in the post-test compared to the pre-test (P<0.05 for HIIT-R; P<0.001 for HIFT). While there was no significant group effect (P=0.127), the time×group interaction effect was significant (P=0.0001). Therefore, both HIFT and HIIT-R were able to improve FMS values in the post-test, and this improvement was greater in the HIFT group than in the HIIT-R group (Table 2).

Anthropometric measures

The results of the repeated measures test for weight showed that the effect of time was not significant (P=0.574). Also, there was no significant group effect (P=0.196). However, the time×group interaction effect was significant (P=0.006), which, when comparing these three groups, shows that HIFT training was able to reduce weight values in the post-test compared to the control group.

For BMI, the effect of time was significant (P=0.0001). A pairwise comparison of the pre-test and post-test results for the groups showed that both the HIIT-R and HIFT groups were able to reduce BMI compared to the pre-test (P<0.01 for all). While there was no significant group effect (P=0.263), the time×group interaction effect was significant (P=0.0001), which, when comparing these three groups, shows that both types of HIFT and HIIT-R training were able to reduce BMI values in the post-test compared to the control group (Table 2).

For WHR, both the time effect (P=0.138) and time×group interaction effect (P=0.314) were not significant. Therefore, the two training protocols did not affect this variable (Table 2).

Discussion

The results of the present study showed that both HIIT-R and HIFT protocols significantly impacted physical fitness indices (agility and VO2max); however, only the effect on VO2max was significant compared to the control group. Nevertheless, HIFT training had a greater impact on physical fitness indices compared to HIIT-R. Both training modalities were effective in improving functional performance and BMI. The HIFT protocol demonstrated a greater effect on functional and anthropometric indices than HIIT-R. Moreover, a significant difference in weight was observed only in the HIFT group compared to the control group.

HIIT-R is widely used, but despite its benefits, it may not always be practical due to limited facilities, low variety, and high difficulty, which can affect adherence [30]. Studies show that HIIT-R training effectively enhances aerobic and anaerobic capacity. For example, an eight-week HIIT-R program at 80% maximum heart rate, with a work-to-rest ratio of 0.8 (60 seconds of activity and 75 seconds of rest), and lasting 23 minutes per session, resulted in increased VO2max, significant reductions in BMI and diastolic blood pressure, and no change in fasting blood glucose levels [31]. Nourry et al. examined an eight-week HIIT-R program at 80% of maximum aerobic speed, with equal work-to-rest ratios, 10-20 seconds of rest, and 30 minutes per session. They found significant improvements in forced vital capacity, VO2max, and peak power, with no effect on maximum heart rate or body fat percentage [32]. Gamelin et al. studied a seven-week HIIT-R program at 100-190% maximal aerobic velocity (MAV), with work-to-rest ratios ranging from 0.3 to 1.5 (5-30 seconds of activity, 15-30 seconds of rest, for 30 minutes per session). They observed significant changes in body mass, VO2max, and MAV [33]. Bauer et al. emphasized the importance of improving cardiorespiratory fitness to reduce cardiovascular risk in children and adolescents [31, 34], as well as cardiometabolic risk in adolescents [35]. Compared to other forms of training, such as low to moderate-intensity running or walking, both in-school and out-of-school, HIIT-R led to greater improvements in cardiovascular indicators and biomarkers of cardiovascular diseases in children and adolescents [36]. Therefore, the positive effects of HIIT-R on physical fitness and body composition is well-documented, which is consistent with the findings of the present study.

In contrast, HIFT has gained great popularity, even among individuals with chronic conditions, due to its varied and functional nature and metabolic benefits [23, 37, 38]. The research comparing HIIT-R and HIFT protocols is limited, highlighting the importance of understanding the effectiveness of these two training methods. A review of the literature shows that both HIIT-R and HIFT, conducted for 12 weeks, positively impact body composition and aerobic fitness in female students (average age: 20.45 years, BMI: 22.15 kg/m2). HIIT-R involved 30 seconds of activity followed by 30 seconds of rest (1:1 ratio), while HIFT involved a 2:1 work-to-rest ratio. Both training types significantly improved VO2max and body fat percentage, with HIFT also enhancing muscular performance (sit-ups and jumps). Neither training type had a significant effect on the waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) or BMI [39]. Therefore, it is concluded that HIFT is as effective as HIIT-R in improving body composition and aerobic fitness, with additional benefits for muscular performance. Gavanda et al. investigated the effects of a six-week HIFT program compared to strength training and endurance training on strength and endurance performance in adolescents (average age: 17 years). The HIFT group showed significant improvements in all performance tests (countermovement jump (CMJ), 20-m sprint (20 m), 3-repetition maximum back squat (3RM), and Yo-Yo test), while the strength training (CMJ, 3RM, and Yo-Yo test) and endurance training (CMJ, 20 m, and Yo-Yo test) groups showed significant improvements in only three performance variables [40]. In a study focused on overweight individuals, Cao et al. compared the effects of HIIT-R and HIFT on body composition, cardiorespiratory fitness, and muscular fitness in young adults (average age: 22.34 years, BMI: 25.43 kg/m2). The 12-week program included 4 sets of 30 seconds of activity and rest, progressing from 100% of maximal aerobic speed (MAS) in weeks 1-4 to 120% of MAS in weeks 9-12. Both training modalities led to significant improvements in muscle strength (long jump, push-ups, handgrip strength, and back strength), cardiorespiratory fitness (20-meter shuttle run, MAS, and VO2max), and body composition (lean mass, body fat percentage, and visceral fat area). However, HIFT had a more substantial positive impact on muscular fitness, likely due to greater increases in lean mass [38].

Comparatively, HIFT’s greater impact on physical fitness variables (agility and VO2max) may be due to the improved muscle strength and endurance, as well as increased lean body mass, which HIIT-R lacks due to the absence of resistance training [38-41]. Also, HIFT’s benefits for VO2max have been previously documented [29]. For FMS, the similarity in movement patterns between HIFT training and the FMS test likely contributes to its effectiveness. Given the lack of impact of these training protocols on WHR and their minimal effect on weight, further studies are needed to understand the reasons behind their influence on BMI.

One of the main limitations of this study is the relatively small sample size, which may affect the statistical power and generalizability of the findings. Additionally, the absence of long-term follow-up prevents the evaluation of the sustainability of training effects. The lack of dietary control may have influenced anthropometric and functional outcomes. Future research should consider measuring lean body mass alongside body fat percentage in a laboratory setting, implementing dietary monitoring, and conducting long-term follow-ups. Moreover, clinical trials with larger and more diverse populations are recommended to strengthen the validity and applicability of the results.

Conclusion

The six-week HIFT training significantly enhanced physical fitness indices (agility and VO2max), FMS, and BMI in overweight and obese adolescents. Moreover, HIFT training can serve as a suitable alternative to HIIT-R workouts, demonstrating even greater effects on VO2max and potentially promoting muscle mass, strength, and endurance, thereby addressing key challenges faced by overweight and obese adolescents.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committee of the Physical Education and Sport Sciences Research Institute, Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.SSRC.REC.1404.044).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection and analysis, interpretation of the results, and drafting of the manuscript. Each author approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support of the participants, without whose active contributions, the study could not have been completed successfully.

References

- Nieto-Vazquez I, Fernández-Veledo S, Krämer DK, Vila-Bedmar R, Garcia-Guerra L, Lorenzo M. Insulin resistance associated to obesity: the link TNF-alpha. Archives of Physiology and Biochemistry. 2008; 114(3):183-94. [DOI:10.1080/13813450802181047] [PMID]

- García-Hermoso A, Ceballos-Ceballos RJ, Poblete-Aro CE, Hackney AC, Mota J, Ramírez-Vélez R. Exercise, adipokines and pediatric obesity: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. International Journal of Obesity (2005). 2017; 41(4):475-82. [DOI:10.1038/ijo.2016.230] [PMID]

- Ruan Y, Mo M, Joss-Moore L, Li YY, Yang QD, Shi L, et al. Increased waist circumference and prevalence of type 2 diabetes and hypertension in Chinese adults: two population-based cross-sectional surveys in Shanghai, China. BMJ Open. 2013; 3(10):e003408. [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003408] [PMID]

- Jung UJ, Choi MS. Obesity and its metabolic complications: the role of adipokines and the relationship between obesity, inflammation, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2014; 15(4):6184-223. [DOI:10.3390/ijms15046184] [PMID]

- Sokhandani M, Vizeshfar F. [Study of the prevalence of obesity and knowledge of Lar high school students about obesity related diseases in Larestan in 2009: A Short Report (Persian)]. Journal of Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences. 2013; 12(2):165-72. [Link]

- Barros WMA, da Silva KG, Silva RKP, Souza APDS, da Silva ABJ, Silva MRM, et al. Effects of overweight/obesity on motor performance in children: A systematic review. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2022; 12:759165. [DOI:10.3389/fendo.2021.759165] [PMID]

- Guzmán-Muñoz E, Mendez-Rebolledo G, Núñez-Espinosa C, Valdés-Badilla P, Monsalves-Álvarez M, Delgado-Floody P, et al. Anthropometric profile and physical activity level as predictors of postural balance in overweight and obese children. Behavioral Sciences (Basel, Switzerland). 2023; 13(1):73. [DOI:10.3390/bs13010073] [PMID]

- Zhu YC, Wu SK, Cairney J. Obesity and motor coordination ability in Taiwanese children with and without developmental coordination disorder. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2011; 32(2):801-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.ridd.2010.10.020] [PMID]

- Mannarino S, Santacesaria S, Raso I, Garbin M, Pipolo A, Ghiglia S, et al. Benefits in cardiac function from a remote exercise program in children with obesity. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(2):1544. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph20021544] [PMID]

- Coquart JB, Lemaire C, Dubart AE, Luttembacher DP, Douillard C, Garcin M. Intermittent versus continuous exercise: effects of perceptually lower exercise in obese women. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2008; 40(8):1546-53. [DOI:10.1249/mss.0b013e31816fc30c] [PMID]

- Racil G, Coquart JB, Elmontassar W, Haddad M, Goebel R, Chaouachi A, et al. Greater effects of high- compared with moderate-intensity interval training on cardio-metabolic variables, blood leptin concentration and ratings of perceived exertion in obese adolescent females. Biology of Sport. 2016; 33(2):145-52. [DOI:10.5604/20831862.1198633] [PMID]

- Kilpatrick MW, Jung ME, Little JP. High-intensity interval training: A review of physiological and psychological responses. ACSM’s Health & Fitness Journal. 2014; 18(5):11-6. [DOI:10.1249/FIT.0000000000000067]

- Engel FA, Ackermann A, Chtourou H, Sperlich B. High-Intensity interval training performed by young athletes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Physiology. 2018; 9:1012. [DOI:10.3389/fphys.2018.01012] [PMID]

- Paquette M, Le Blanc O, Lucas SJ, Thibault G, Bailey DM, Brassard P. Effects of submaximal and supramaximal interval training on determinants of endurance performance in endurance athletes. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports. 2017; 27(3):318-26. [DOI:10.1111/sms.12660] [PMID]

- Poon ET, Siu PM, Wongpipit W, Gibala M, Wong SH. Alternating high-intensity interval training and continuous training is efficacious in improving cardiometabolic health in obese middle-aged men. Journal of Exercise Science and Fitness. 2022; 20(1):40-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.jesf.2021.11.003] [PMID]

- Feito Y, Heinrich KM, Butcher SJ, Poston WSC. High-Intensity Functional Training (HIFT): Definition and research implications for improved fitness. Sports (Basel). 2018; 6(3):76. [DOI:10.3390/sports6030076] [PMID]

- Feito Y, Hoffstetter W, Serafini P, Mangine G. Changes in body composition, bone metabolism, strength, and skill-specific performance resulting from 16-weeks of HIFT. Plos One. 2018; 13(6):e0198324. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0198324] [PMID]

- Poston WS, Haddock CK, Heinrich KM, Jahnke SA, Jitnarin N, Batchelor DB. Is High-Intensity Functional Training (HIFT)/CrossFit Safe for Military Fitness Training? Military Medicine. 2016; 181(7):627-37. [DOI:10.7205/milmed-d-15-00273] [PMID]

- Heinrich KM, Becker C, Carlisle T, Gilmore K, Hauser J, Frye J, et al. High-intensity functional training improves functional movement and body composition among cancer survivors: A pilot study. European Journal of Cancer Care. 2015; 24(6):812-7. [DOI:10.1111/ecc.12338] [PMID]

- Feito Y, Patel P, Sal Redondo A, Heinrich KM. Effects of eight weeks of high intensity functional training on glucose control and body composition among overweight and obese adults. Sports (Basel). 2019; 7(2):51. [DOI:10.3390/sports7020051] [PMID]

- Church TS, Blair SN, Cocreham S, Johannsen N, Johnson W, Kramer K, et al. Effects of aerobic and resistance training on hemoglobin A1c levels in patients with type 2 diabetes: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010; 304(20):2253-62. [DOI:10.1001/jama.2010.1710] [PMID]

- AminiLari Z, Fararouei M, Amanat S, Sinaei E, Dianatinasab S, AminiLari M, et al. The effect of 12 weeks aerobic, resistance, and combined exercises on omentin-1 levels and insulin resistance among type 2 diabetic middle-aged women. Diabetes & Metabolism Journal. 2017; 41(3):205-12. [DOI:10.4093/dmj.2017.41.3.205] [PMID]

- Heinrich KM, Patel PM, O'Neal JL, Heinrich BS. High-intensity compared to moderate-intensity training for exercise initiation, enjoyment, adherence, and intentions: An intervention study. BMC Public Health. 2014; 14:789. [DOI:10.1186/1471-2458-14-789] [PMID]

- Mardokhi M, Rahimi MR, Saedmocheshi S, Vasquez-Muñoz M, Andrade DC. L-arginine Supplementation Does Not Enhance Anaerobic Performance in Trained Female Handball Players. Journal of Human Kinetics. 2025; 99:67. [DOI:10.5114/jhk/197336]

- Spilz A, Munz M. Automatic assessment of functional movement screening exercises with deep learning architectures. Sensors. 2022; 23(1):5. [DOI:10.3390/s23010005] [PMID]

- Dinc E, Kilinc BE, Bulat M, Erten YT, Bayraktar B. Effects of special exercise programs on functional movement screen scores and injury prevention in preprofessional young football players. Journal of Exercise Rehabilitation. 2017; 13(5):535-40. [DOI:10.12965/jer.1735068.534] [PMID]

- Marfell-Jones M, Olds T, Stewart A, Lindsay Carter LE. International society for the advancement of kinanthropometry. Underdale, SA: The University of South Australia Holbrooks Rd; 2012.

- Ferrari Bravo D, Impellizzeri FM, Rampinini E, Castagna C, Bishop D, Wisloff U. Sprint vs. interval training in football. International Journal of Sports Medicine. 2008; 29(8):668-74. [DOI:10.1055/s-2007-989371] [PMID]

- Bermejo FJ, Camacho GJ, Guardado IM, Andrada RT. Effects of a HIIT protocol including functional exercises on performance and body composition. Archivos de Medicina del Deporte. 2018; 35(6):386-91. [Link]

- Roy M, Williams SM, Brown RC, Meredith-Jones KA, Osborne H, Jospe M, et al. High-Intensity interval training in the real world: Outcomes from a 12-month intervention in overweight adults. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2018; 50(9):1818-26. [DOI:10.1249/mss.0000000000001642] [PMID]

- Bauer N, Sperlich B, Holmberg HC, Engel FA. Effects of high-intensity interval training in school on the physical performance and health of children and adolescents: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Sports Medicine-Open. 2022; 8(1):50. [DOI:10.1186/s40798-022-00437-8] [PMID]

- Nourry C, Deruelle F, Guinhouya C, Baquet G, Fabre C, Bart F, et al. High-intensity intermittent running training improves pulmonary function and alters exercise breathing pattern in children. European Journal of Applied Physiology. 2005; 94(4):415-23. [DOI:10.1007/s00421-005-1341-4] [PMID]

- Gamelin FX, Baquet G, Berthoin S, Thevenet D, Nourry C, Nottin S, et al. Effect of high intensity intermittent training on heart rate variability in prepubescent children. European Journal of Applied Physiology. 2009; 105(5):731-8. [DOI:10.1007/s00421-008-0955-8] [PMID]

- Ortega FB, Ruiz JR, Castillo MJ, Sjöström M. Physical fitness in childhood and adolescence: A powerful marker of health.International Journal of Obesity. 2008; 32(1):1-11. [DOI:10.1038/sj.ijo.0803774] [PMID]

- Roldão da Silva P, Castilho Dos Santos G, Marcio da Silva J, Ferreira de Faria W, Gonçalves de Oliveira R, Stabelini Neto A. Health-related physical fitness indicators and clustered cardiometabolic risk factors in adolescents: A longitudinal study. Journal of Exercise Science & Fitness. 2020; 18(3):162-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.jesf.2020.06.002] [PMID]

- van Biljon A, McKune AJ, DuBose KD, Kolanisi U, Semple SJ. Do short-term exercise interventions improve cardiometabolic risk factors in children? The Journal of Pediatrics. 2018; 203:325-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.07.067] [PMID]

- Nieuwoudt S, Fealy CE, Foucher JA, Scelsi AR, Malin SK, Pagadala M, et al. Functional high-intensity training improves pancreatic β-cell function in adults with type 2 diabetes. American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2017; 313(3):E314-20. [DOI:10.1152/ajpendo.00407.2016] [PMID]

- Cao M, Yang B, Tang Y, Wang C, Yin L. Effects of low-volume functional and running high-intensity interval training on physical fitness in young adults with overweight/obesity. Frontiers in Physiology. 2024; 15:1325403. [DOI:10.3389/fphys.2024.1325403] [PMID]

- Lu Y, Wiltshire HD, Baker JS, Wang Q. The effects of running compared with functional high-intensity interval training on body composition and aerobic fitness in female university students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(21):11312. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph182111312] [PMID]

- Gavanda S, Isenmann E, Geisler S, Faigenbaum A, Zinner C. The effects of high-intensity functional training compared with traditional strength or endurance training on physical performance in adolescents: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2022; 36(3):624-32. [DOI:10.1519/jsc.0000000000004221] [PMID]

- Kim YJ, Moon S, Yu JM, Chung HS. Implication of diet and exercise on the management of age-related sarcopenic obesity in Asians. Geriatrics & Gerontology International. 2022; 22(9):695-704. [DOI:10.1111/ggi.14442] [PMID]

Type of Study: Original Article |

Subject:

Health

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |