Volume 13, Issue 4 (Autumn 2025)

Iran J Health Sci 2025, 13(4): 285-296 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: IR.HSU.REC.1402.001

Clinical trials code: IR.HSU.REC.1402.001

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Koujori A, Askari R, Haghighi A H. Land Versus Aquatic Exercise: Effects on ANGPTL4 and Postural Control in Elderly Men With Metabolic Syndrome. Iran J Health Sci 2025; 13 (4) :285-296

URL: http://jhs.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-1030-en.html

URL: http://jhs.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-1030-en.html

Department of Sports Physiology, Faculty of Sport Sciences, Hakim Sabzevari University, Sabzevar, Iran. , r.askari@hsu.ac.ir

Keywords: Metabolic syndrome (MetS), Middle-aged adults, Exercise therapy, Postural balance, Angiopoietin-like 4

Full-Text [PDF 967 kb]

(3 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (501 Views)

Full-Text: (3 Views)

Introduction

The increasing prevalence of the elderly population, along with the associated health challenges faced by older individuals, represents a significant concern for the international community. Aging is often accompanied by physical frailty and a decline in cognitive function [1]. The demographic shift toward an aging global population is a critical factor contributing to the rising incidence of metabolic syndrome (MetS), as older adults frequently exhibit a combination of cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors that characterize this syndrome [2]. Key indicators of MetS include increased waist circumference, elevated fasting serum glucose levels, heightened serum triglyceride levels, hypertension, and decreased levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL). The diagnosis of MetS necessitates the presence of three or more of these specified criteria [3].

Several proteins are recognized as being exclusively or predominantly secreted by the liver, exerting a direct influence on energy metabolism. These proteins, referred to as hepatokines, are integral to the modulation of insulin resistance and the enhancement of metabolic variables in individuals with type 2 diabetes [4]. Angiopoietin-like proteins (ANGPTLs) are liver-derived factors that share structural similarities with angiopoietin. Notably, ANGPTLs 3, 4, and 8 are critical in the regulation of lipid metabolism, primarily functioning to inhibit the activity of lipoprotein lipase (LPL) in circulation through specific binding interactions [5, 6]. ANGPTL4 is predominantly released from the liver in response to exercise. Furthermore, weight gain has been associated with elevated serum levels of ANGPTL4, whereas weight loss correlates with a reduction in its levels among young and middle-aged adults [6]. Nevertheless, there is a paucity of information regarding the effects of exercise combined with weight loss on ANGPTL4 expression levels in skeletal muscle and serum among older adults with metabolic syndrome [7]. Recent studies also suggest that high systemic levels of ANGPTL4, often observed in inflammatory conditions and obesity, may contribute to muscle atrophy and reduced mitochondrial function by inducing insulin resistance and disrupting insulin signaling in muscle. This, in turn, can indirectly affect individuals’ balance [8].

Falls are recognized as a significant health issue among the aging population, with fall-related injuries—including fractures, disabilities, substantial financial burdens on governments and families, and mortality—being a primary concern for the World Health Organization (WHO). Consequently, the identification of risk factors and specific preventive strategies for falls among the elderly is of paramount importance [9]. Balance is a highly complex function that encompasses both musculoskeletal and nervous system components. Functional factors influencing balance include vision, hearing, vestibular sense, proprioception, spatial perception, environmental changes, muscular strength, endurance, joint flexibility, and the central nervous system’s response to specific stimuli [10]. Age-related physical and physiological changes are associated with diminished flexibility, agility, speed, and balance [11]. Reduced muscular strength and decreased efficiency of the cardiovascular-respiratory system with advancing age contribute to this phenomenon. Endurance and resistance training may help sustain cardiovascular-respiratory efficiency, enhance strength, and mitigate joint degeneration [12]. Aquatic exercise has been shown to be effective in maintaining and improving physical performance in healthy older adults [13]. Given that diabetic patients are susceptible to chronic complications, including peripheral neuropathy, and face an increased risk of injuries and foot lesions, water-based exercise or hydrotherapy can be particularly beneficial. When submerged, an individual experiences only 56% of his/her body weight, resulting in minimal joint pressure and a lower risk of injury. Additionally, exercising in water can enhance endurance and muscle tone by increasing pressure on the muscles [14].

However, given that access to water-based exercise may not be universally available and often necessitates costly equipment, it is important to understand the comparative effects of endurance and resistance training in both terrestrial and aquatic environments on inflammatory factors that influence the progression of metabolic syndrome indices and the maintenance of balance performance. This understanding can yield practical insights for this segment of the elderly population and healthcare professionals. Accordingly, this study assessed the impact of combined land-water exercises (WE) on ANGPTL4 expression and balance improvement in elderly patients with metabolic syndrome. It compared the differential effects of these exercises on physical performance metrics and ANGPTL4 modulation to identify optimal intervention strategies.

Materials and Methods

This quasi-experimental study utilized a pre-test/post-test design. Forty-five elderly men with MetS (defined by fasting blood sugar >100 mg/dL [15], triglycerides (TG)>150 mg/dL [16], waist circumference >90 cm) were recruited from the Toooba Clinic at Razi Hospital, Qaemshahr. Exclusion criteria were cardiovascular disease, hormonal disorders, kidney and liver diseases, recent surgery, smoking, changing the dose of medication from previous conditions, and any therapeutic intervention affecting laboratory results. Participants were selected through purposive and convenience sampling and were randomly divided into three groups (n=15 each): The WE group, the land exercise (LE) group, and the control group (CG) who maintained their usual daily activities using a computer-generated random number sequence. A questionnaire on daily calorie consumption and food type was completed by the subjects, and they were asked to adhere to their usual dietary routine during the research period.

The sample size for this study was calculated using G*Power software, version 3.1. An a priori power analysis was conducted for a repeated measures ANOVA (within-between interaction), based on the study’s primary outcome variable: The change in ANGPTL4 concentration. Drawing from previous studies on the effects of exercise training on ANGPTL4, a moderate effect size (f=0.25) was assumed. With the significance level (α) set at 0.05 and the desired statistical power set at 80% (β=0.20), the analysis revealed that a minimum of 14 participants per group was required. To account for a potential 10% attrition rate, we recruited a final sample of 15 participants per group.

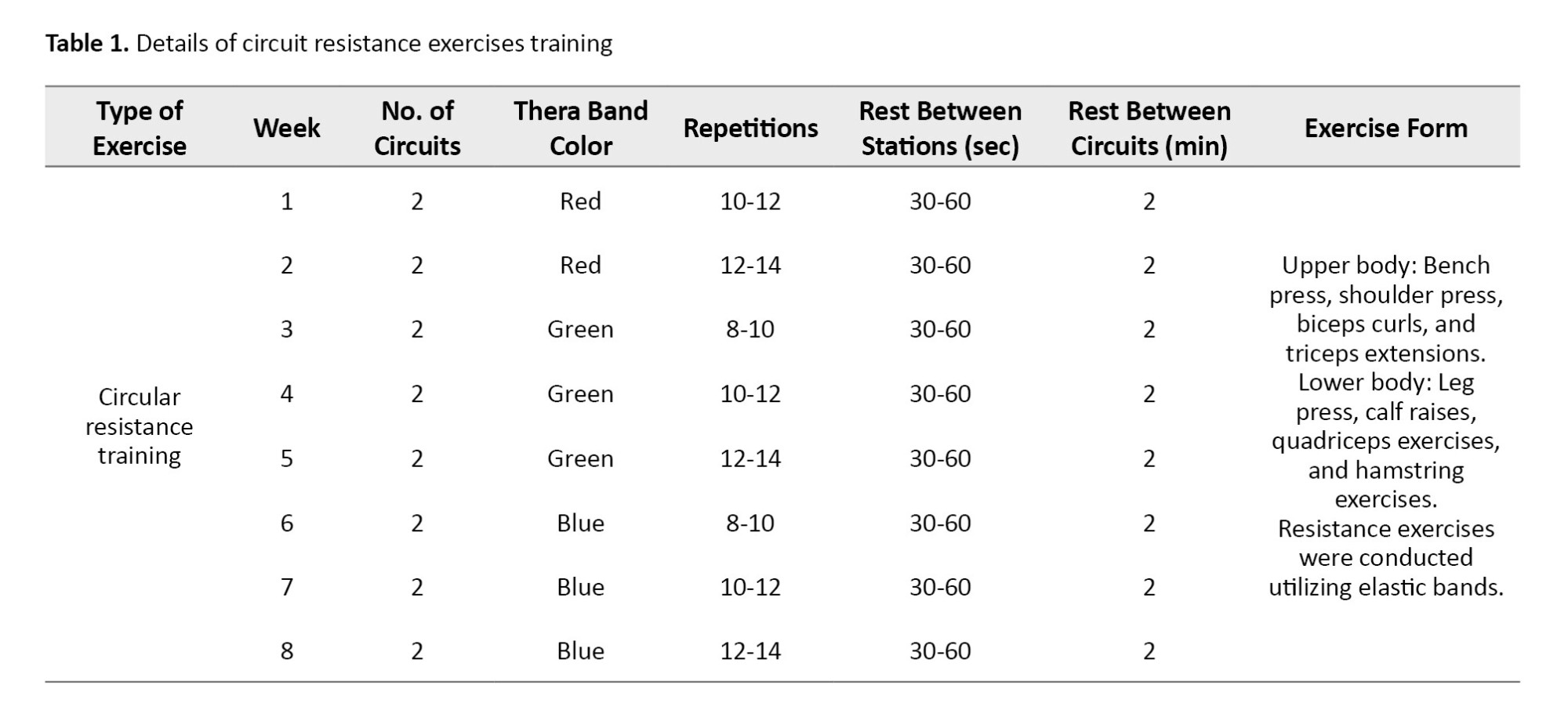

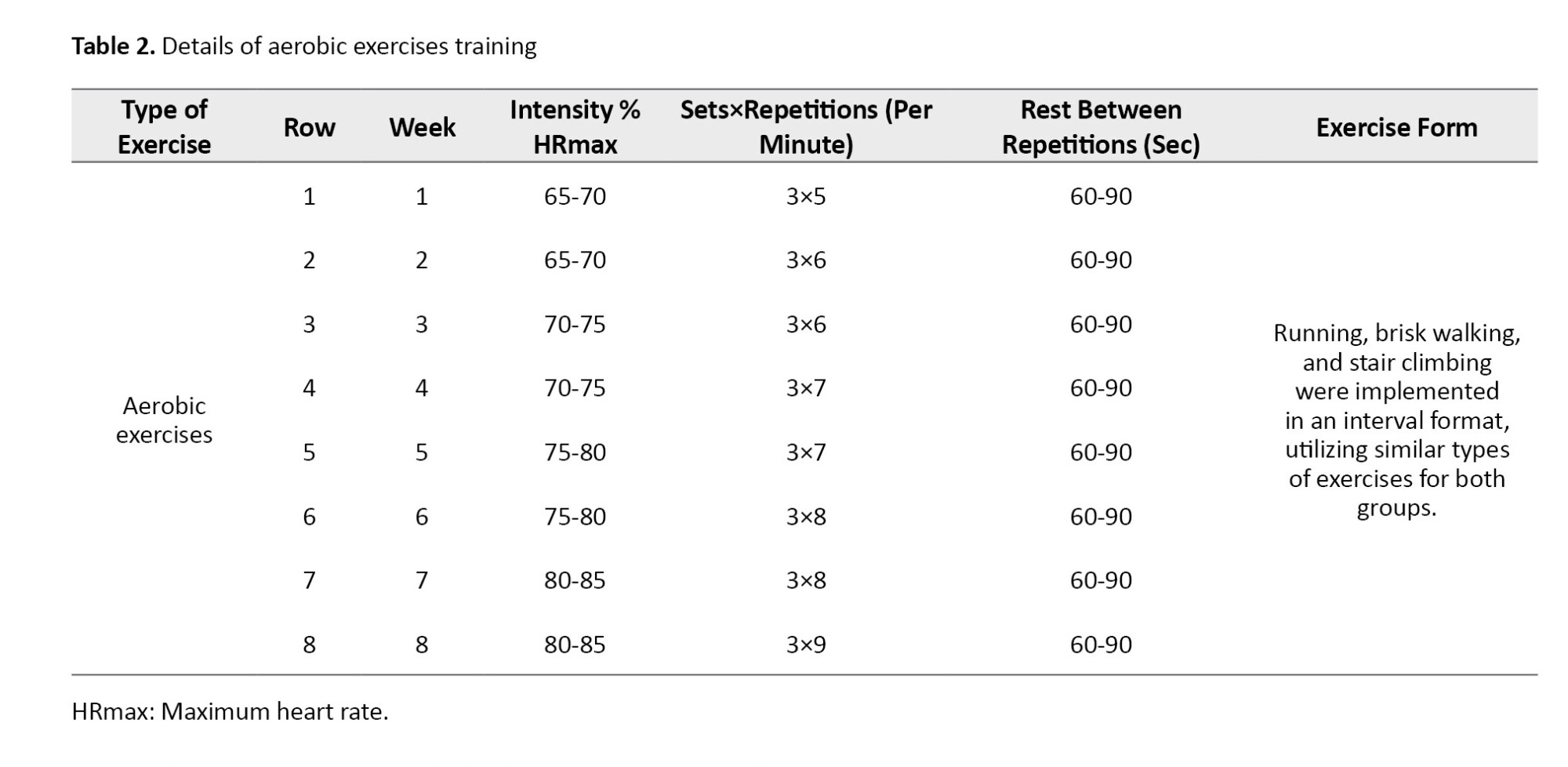

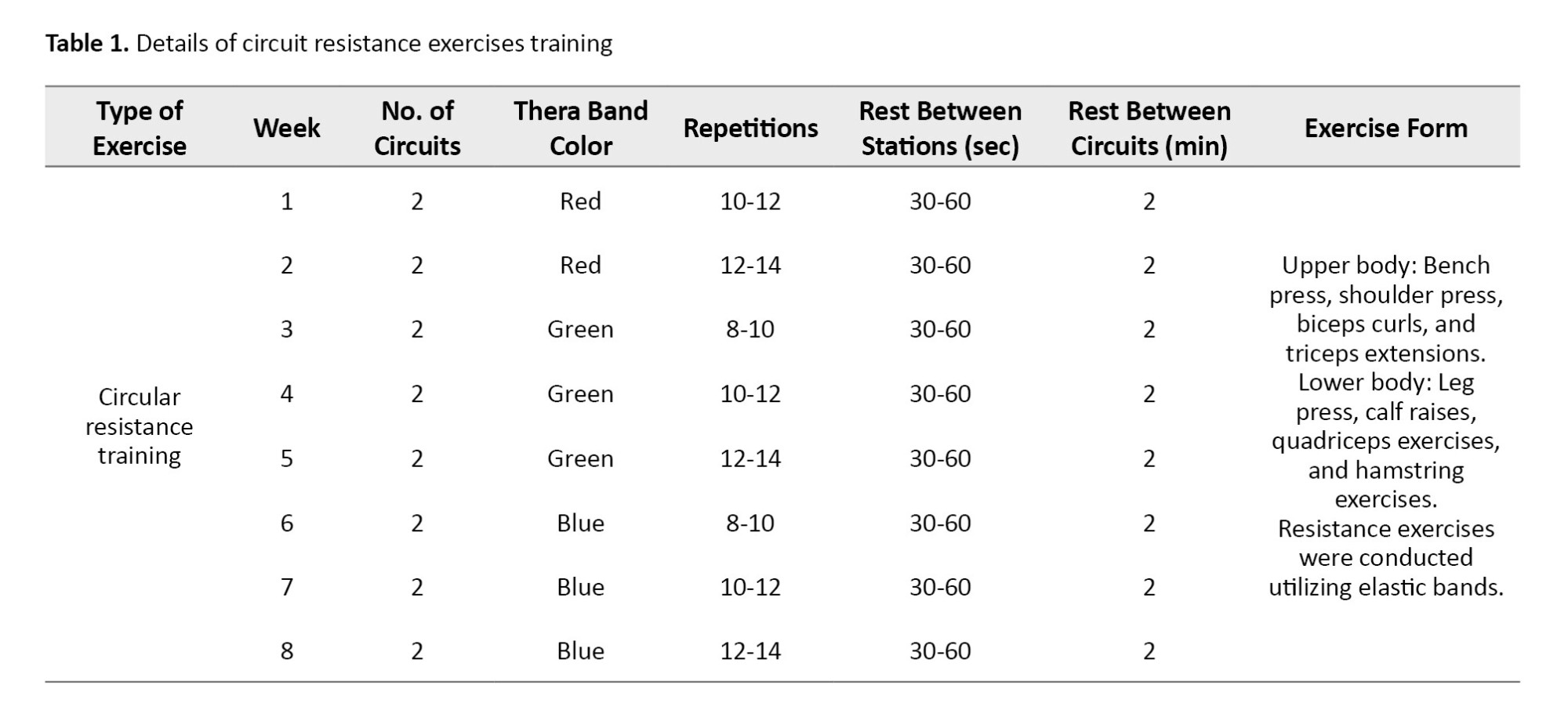

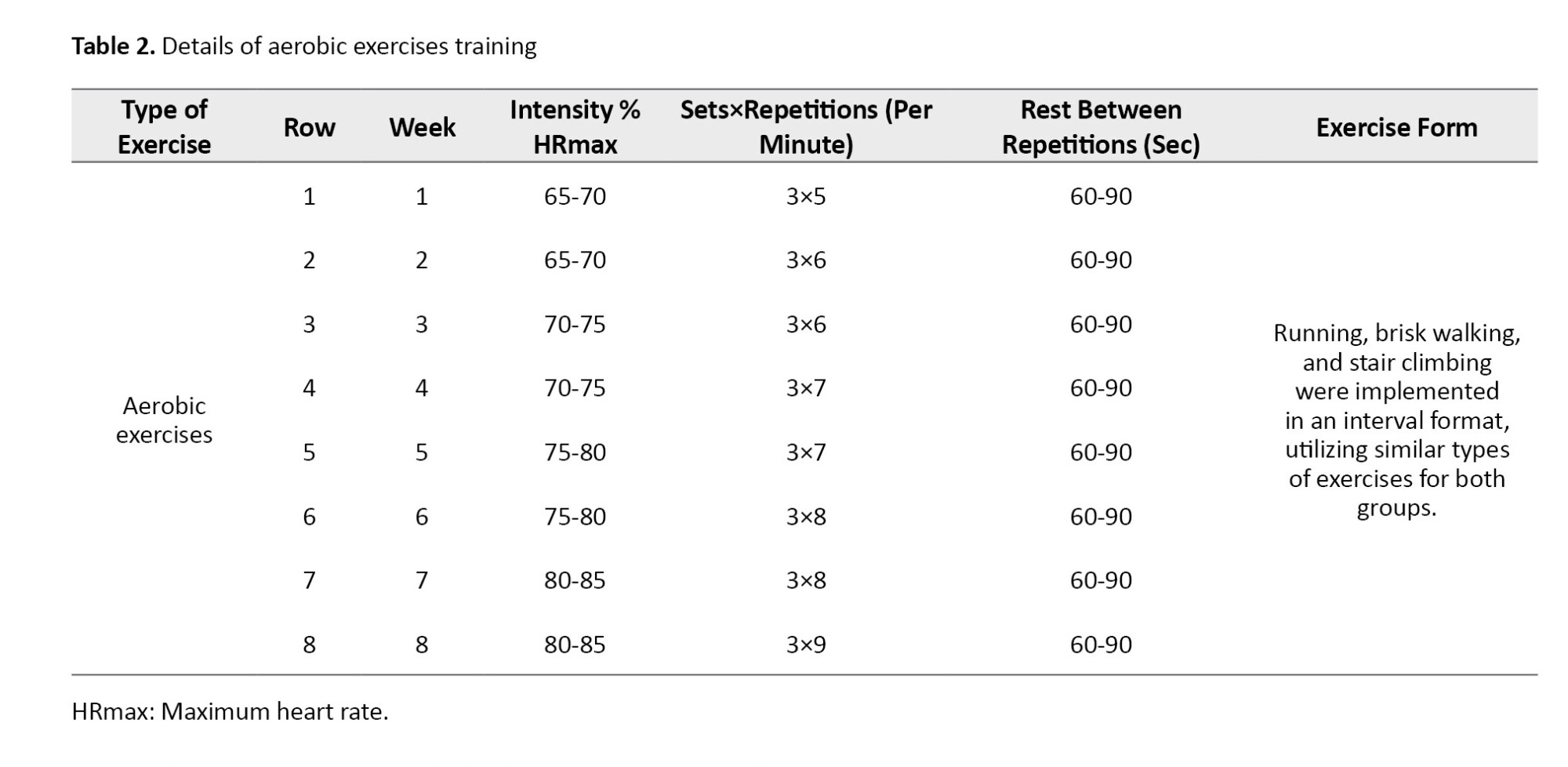

The training program for the exercise groups consisted of three sessions per week for eight weeks (Tables 1 and 2). The elastic bands included colors, such as yellow (light), red (medium), green (heavy), blue (very heavy), black (special heavy), silver (very heavy), and gold (maximum) [17]. Considering the physiological reduction in muscular strength in the elderly and the physical capabilities of the participants, only three colors—red (medium), green (heavy), and blue (very heavy)—were used.

Initially, combined exercises were conducted, followed by a 10-minute active rest period, after which endurance exercises were performed. Exercise intensity was monitored using a Polar chest pulse monitor [18]. To determine the maximum heart rate (HRmax), the age-predicted formula from Fox and Haskell (220-age) was used. Blood samples were collected 24 hours prior to the first exercise session and 48 hours following the final session [19]. The serum obtained from these samples was utilized to measure serum ANGPTL4 levels. Measurements of serum ANGPTL4 levels were conducted using a human-specific Zallbio kit manufactured in Germany, which possesses a sensitivity of 3 ng/mL and employs the sandwich ELISA method [20]. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated using the formula weight (kg) divided by height (m²). Anthropometric indices were assessed utilizing a 3D scanning device (top genesis), manufactured in Iran, to evaluate height, weight, BMI, body fat percentage, and waist circumference (validity and reliability of 0.982) [21]. To assess balance performance indices, including static balance with eyes open and closed, as well as dynamic balance, established tests, such as the Sharpened Romberg test (reliability with eyes open: 0.90-0.91 and reliability with eyes closed: 0.76-0.77) [22] and the functional reach test (FRT) with a validity and reliability of 0.98 [23] were employed. To ensure blinding and reduce the use of subjective judgment, all members of the evaluation team (blood sampling and functional testing) with the exception of the principal investigator, were blinded to the group allocation of the participants.

To evaluate the normality of the data, the Shapiro-Wilk test was used, and to ensure the homogeneity of variances, the Levene’s test was used. Also, before performing repeated measures analysis of variance, the sphericity of the variance difference between the subject groups was evaluated using the Mauchly’s Sphericity test. Considering the results of the Shapiro-Wilk test and the normality of all data except for weight, data analysis using repeated measures ANOVA was used for normal data, and the Friedman test was used for weight. After confirming the normality of the data and before comparing between groups, the Levene’s test was used to ensure the homogeneity of variances. According to the results of the Levene’s test and homogeneity of variance for all data except for the blindfolded balance test, the Bonferroni test was used for other data and the Games-Howell test was used for the blindfolded balance test. A significance threshold of P<0.05 was considered for statistical analysis. To calculate the percentage change, the difference between the final value (post-test) and the initial value (pre-test) was calculated. This result was then divided by the initial value. Finally, the outcome was multiplied by 100 to obtain the percentage (Equation 1):

1. Percentage change=Pre-test mean(Post-test Mean−Pre-test Mean)×100

Results

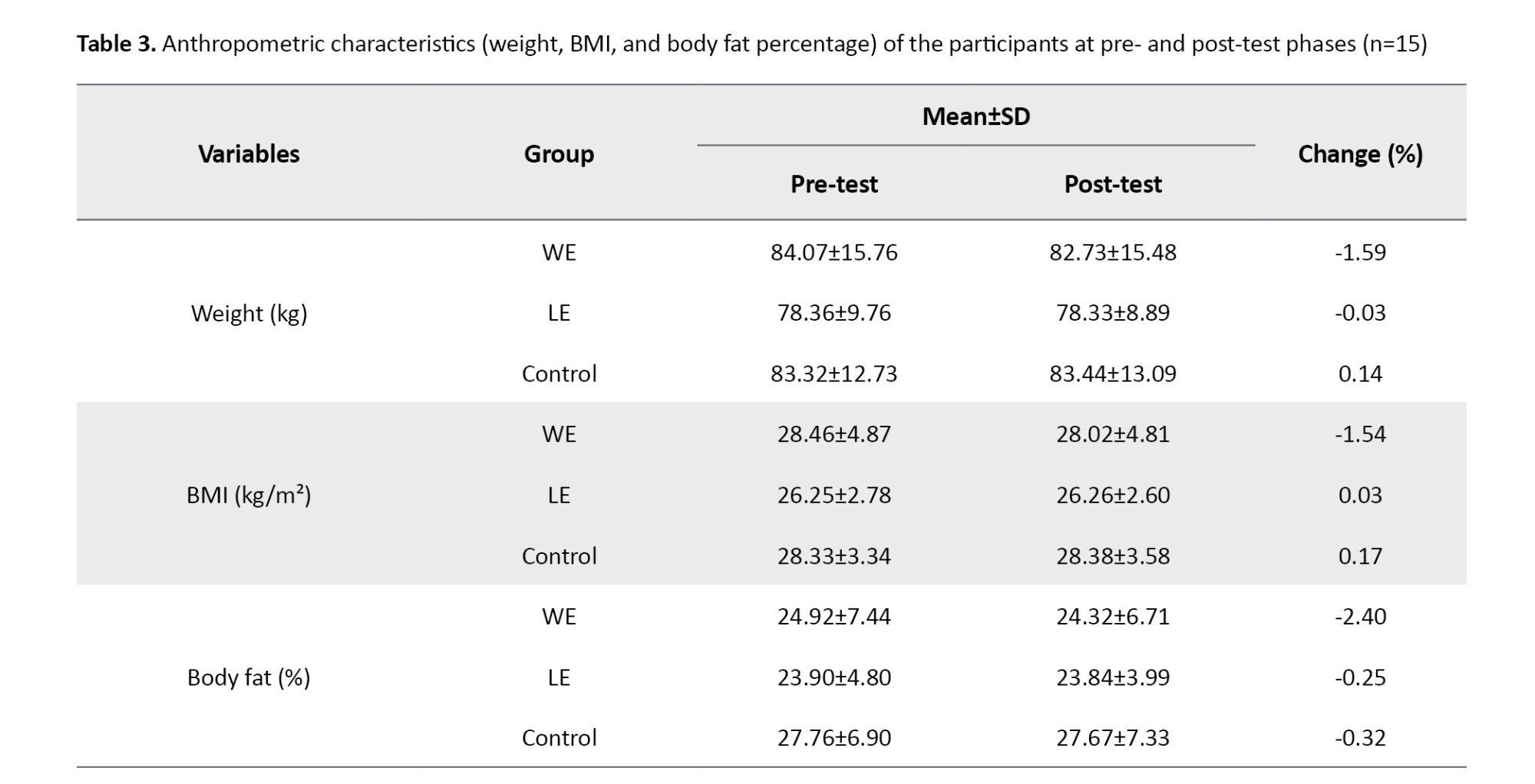

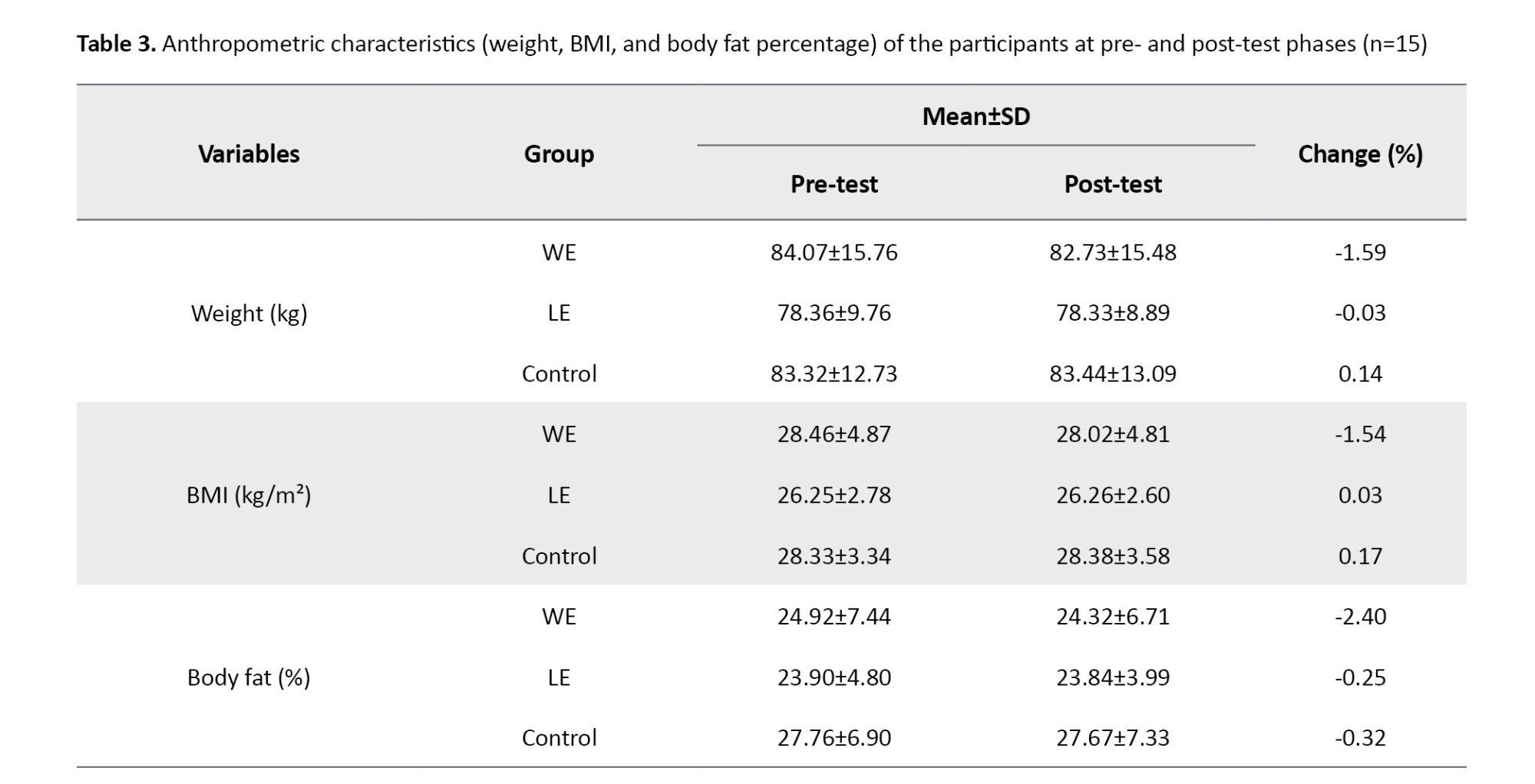

At baseline, the Mean±SD values for the aquatic exercise, land-based exercise, and CGs, respectively, were as follows: Weight: 84.07±15.76 kg, 78.36±9.76 kg, and 83.32±12.73 kg; BMI: 28.46±4.87 kg/m², 26.25±2.78 kg/m², and 28.33±3.34 kg/m², and body fat percentage: 24.92±7.44%, 23.90±4.80%, and 27.76±6.90%.

The results of the descriptive statistics concerning the anthropometric characteristics are presented in Table 3. The percentage changes indicated a decrease in weight and body fat percentage in both exercise groups, as well as a decrease in BMI in the aquatic exercise group.

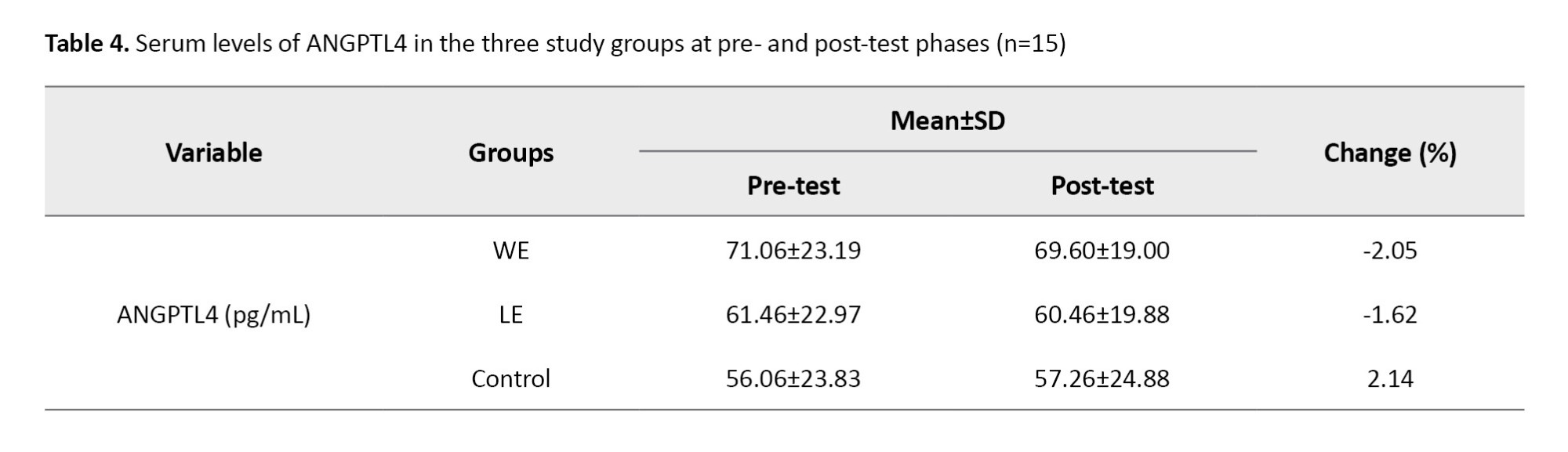

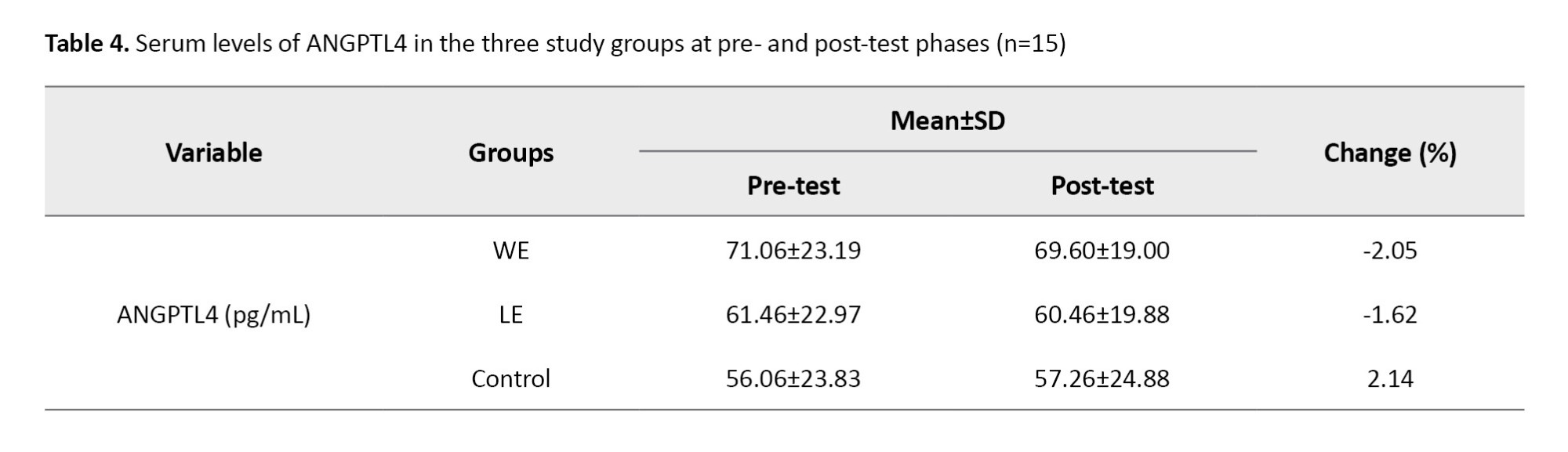

Considering that all indices, with the exception of weight, exhibited a normal distribution (P>0.05), the Games-Howell post-hoc test was employed to identify the specific locations of weight differences. The Levene’s test confirmed homogeneity in body composition variables (BMI and body fat percentage), ANGPTL4 levels, and performance assessments (static balance with eyes open and dynamic balance) (P>0.05). Consequently, when deemed necessary, the Bonferroni post-hoc test was applied (Table 4).

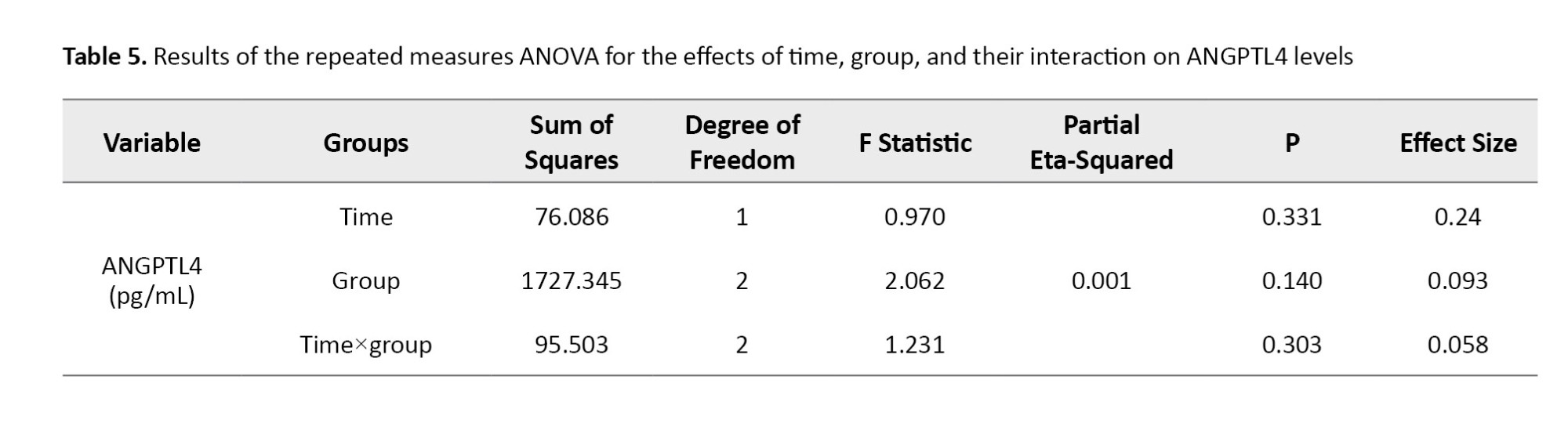

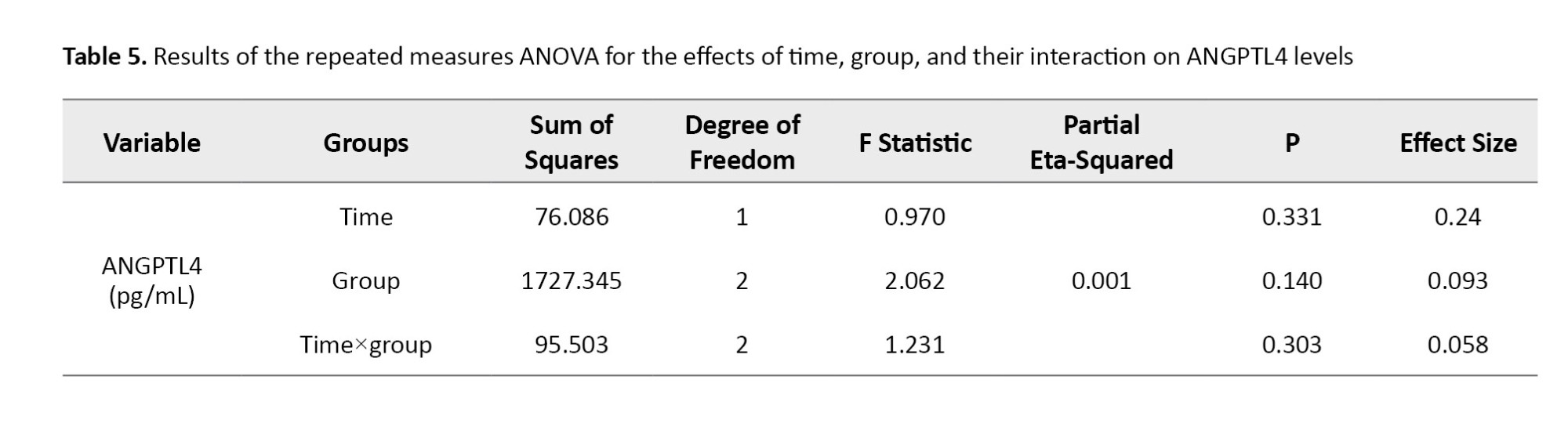

Based on the results presented in Table 5, it is evident that the interaction effect of time within the group for the ANGPTL4 variable (P=0.303) was not statistically significant. This finding suggests that there were no meaningful changes among the three groups examined.

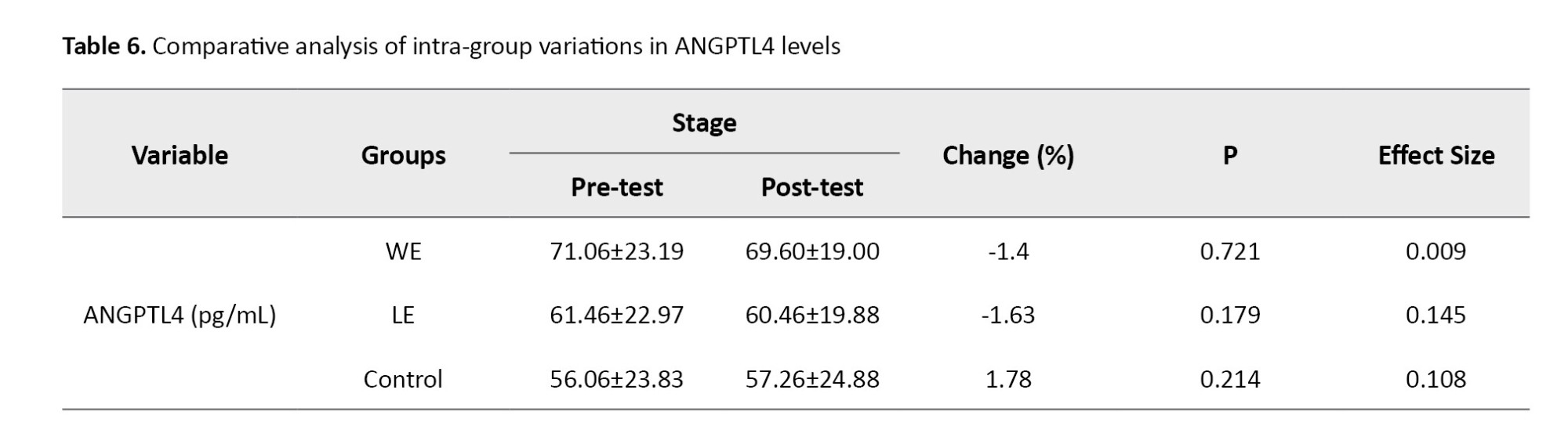

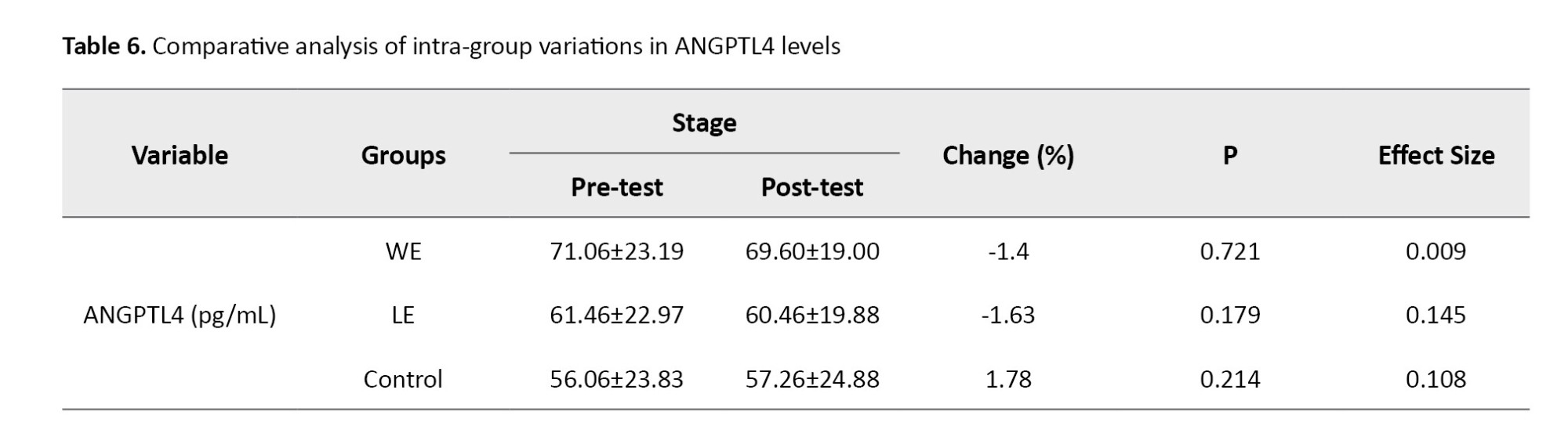

In Table 6, the results of the comparison of mean introversion indicate that, despite the observed decrease in ANGPTL4 levels in the training groups and an increase in the CGs, no statistically significant difference was found among the three study groups.

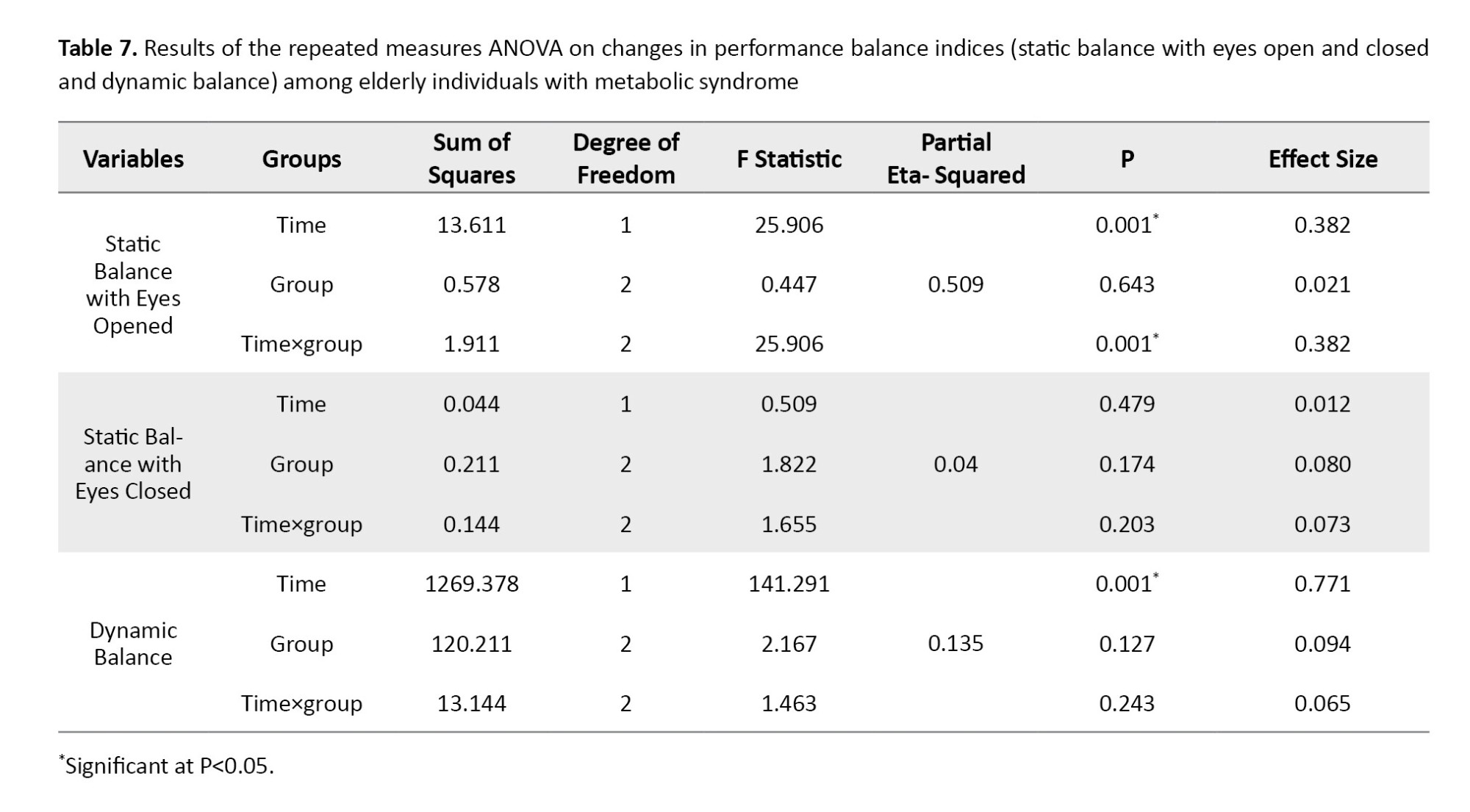

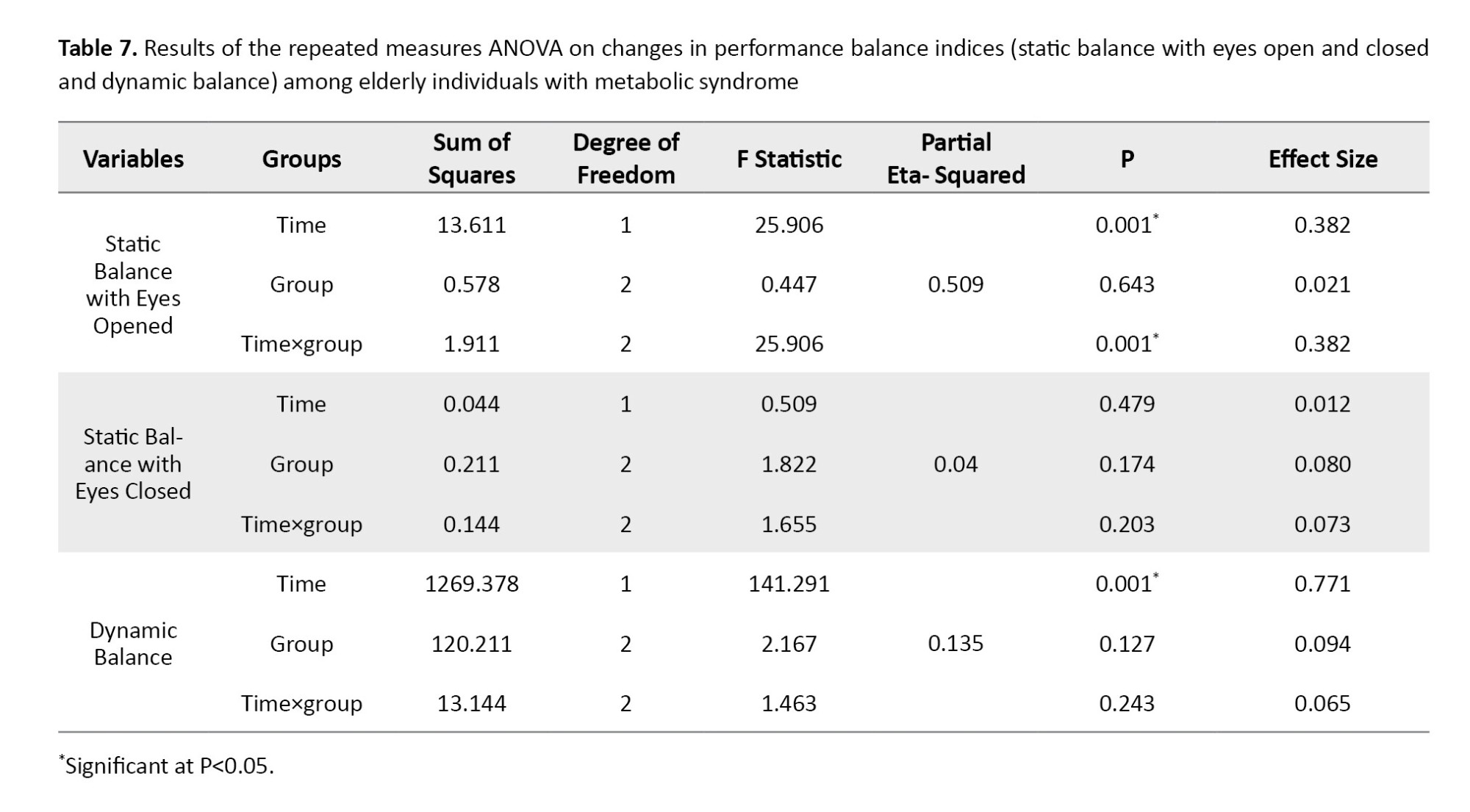

According to the results of Table 7, in the assessment of static balance with eyes open, a statistically significant difference was identified among the study groups (P=0.01). The post-hoc test results did not show significant differences between the groups at the two time points, before and after the study; it appears that the timing of the changes differed from the post-test time. No differences were observed between the groups for the other indices (P>0.05). However, the results of the post-hoc tests did not reveal significant differences between the groups at the two time points measured, both prior to and following the intervention; it seems that the timing of the observed changes diverged from the post-test assessment. Furthermore, no significant differences were noted between the groups concerning the other indices (P=0.24).

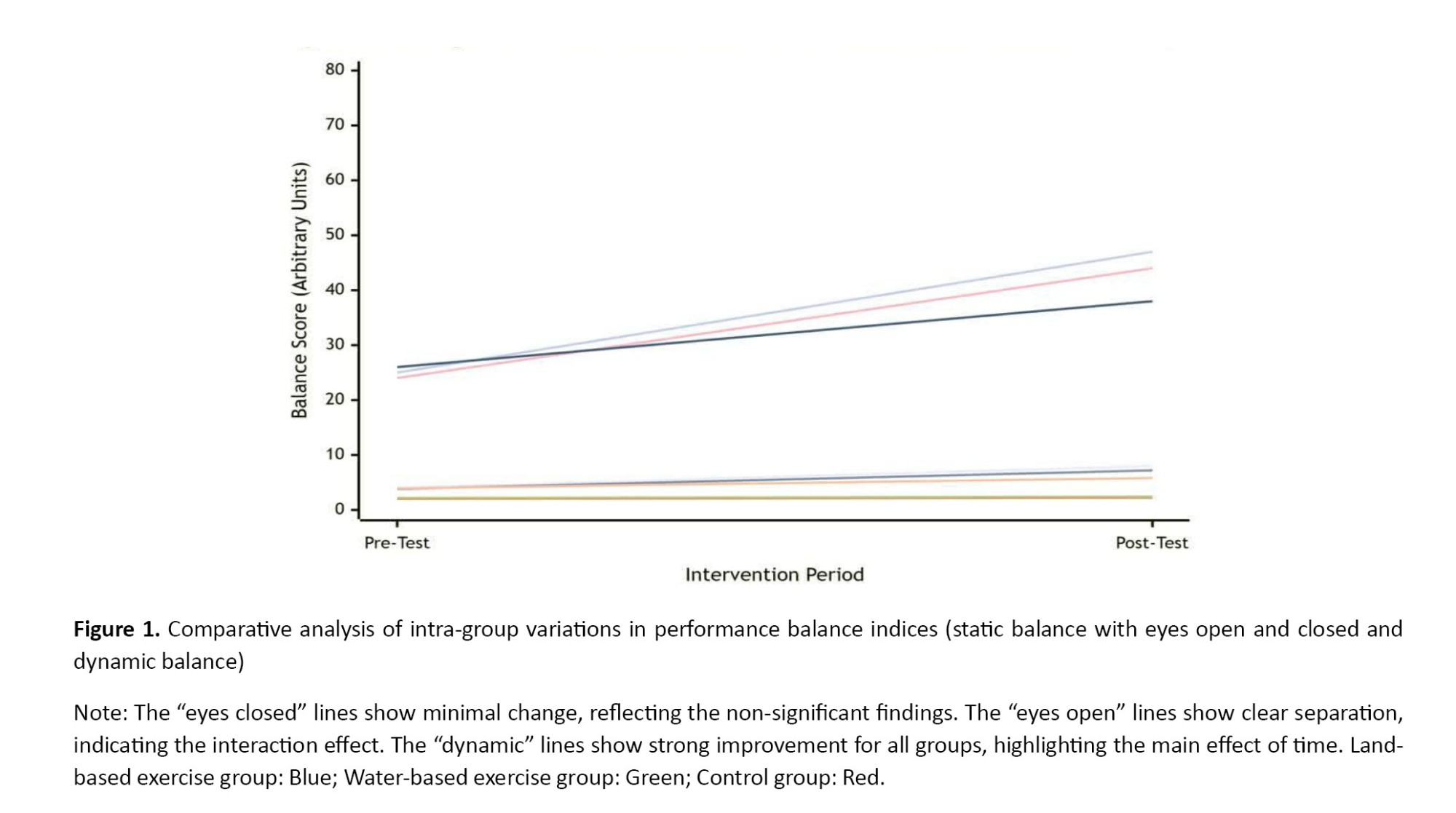

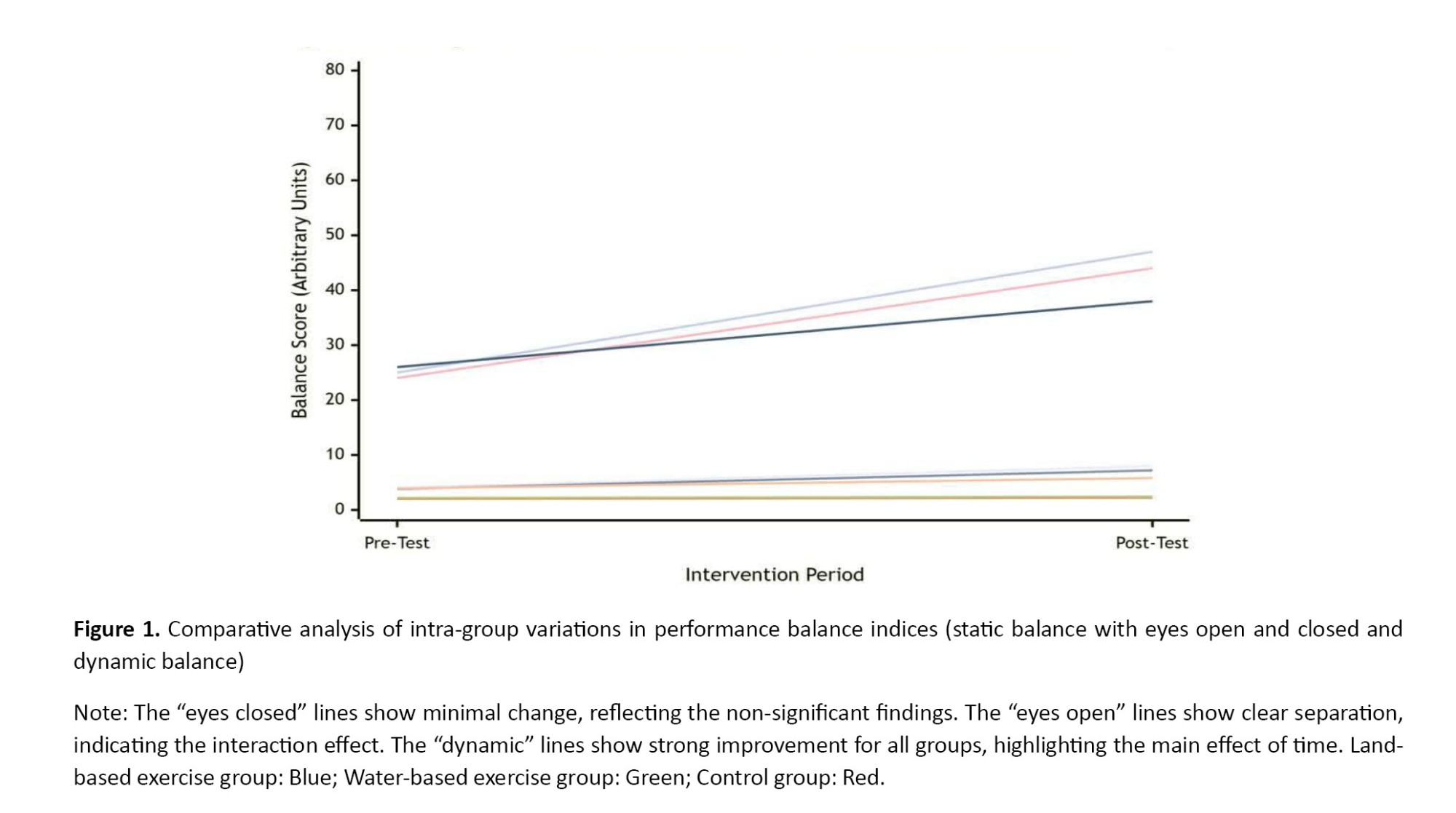

Intra-group mean comparisons indicated that both dynamic balance and static balance with eyes open exhibited significant improvements in all three groups when compared to pre-test measurements (P<0.05) (Figure 1). However, the results of the post-hoc did not reveal significant differences between the groups at the two time points measured, both prior to and following the intervention; it appears that the timing of the observed changes diverged from the post-test assessment. Furthermore, no significant differences were noted between the groups concerning the other indices (P>0.05).

Graph 1 shows significant improvement in eyes-open balance in all groups from pre-test to post-test. The slopes of the different lines indicate that the rate of improvement varied across groups (significant interaction effect), with the first group (likely the land or water training group) likely improving the most (P=0.001). No significant change was observed in eyes-closed balance scores over time and between groups. This graph clearly demonstrates this lack of change (P>0.05). A significant improvement in dynamic balance scores was evident in all groups from pre-test to post-test (P=0.001). Although the group and interaction effects were not significant, the graph shows that all groups benefited from the intervention.

Discussion

The present study’s results, which indicated no statistically significant alterations in ANGPTL4 levels following exercise interventions, are consistent with the existing body of literature.

This finding aligns with that of Li et al. who reported no significant changes in serum or skeletal muscle ANGPTL4 levels following a six-month combined exercise and weight loss program in older adults with obesity. The authors attributed the lack of significant change to participants’ age, BMI, and the type of tissue analyzed, also noting the limitation of a small sample size [7]. Similarly, Banitalebi et al. found that neither sprint interval training (SIT) nor combined aerobic and resistance training (A+R) over 10 weeks induced significant changes in circulating ANGPTL4 levels in middle-aged overweight women with type 2 diabetes. Furthermore, changes in myokines were not correlated with improvements in body composition or metabolic profiles [24]. Further supporting this consensus, Karami et al. observed no significant differences in serum ANGPTL4 following an eight-week regimen of either high-intensity combined training or aerobic-only training in women with type 2 diabetes. They proposed that an exercise duration of less than three months may be insufficient to modulate the molecular mechanisms governing ANGPTL4 secretion via free fatty acid (FA) stimulation [25].

Collectively, these studies, including the present study, suggest that short- to medium-term exercise interventions (up to six months), across various modalities (aerobic, resistance, high-intensity interval, or combined), do not consistently elicit significant changes in ANGPTL4 levels in populations with obesity or type 2 diabetes. The response of this protein appears to be influenced by factors, such as intervention duration, participants’ demographics (age and BMI), and the specific tissue sampled. The consistent lack of change in ANGPTL4 following exercise, as highlighted in the summary, presents an intriguing physiological paradox. ANGPTL4 is a potent inhibitor of LPL, an enzyme crucial for hydrolyzing TG in circulating VLDL and chylomicrons for storage in adipose tissue or oxidation in muscle. During exercise, energy demand in skeletal muscle surges. A logical physiological adaptation would be to suppress ANGPTL4 to disinhibit LPL activity in muscle, thereby facilitating increased FA uptake and oxidation to meet energy needs. Concurrently, a potential increase in ANGPTL4 in adipose tissue could reduce LPL activity there, redirecting lipid flux away from storage and toward working muscle. This tissue-specific regulation is a central hypothesis in exercise metabolism [26]. The body’s energy regulation is highly redundant. Other pathways may compensate to ensure fuel delivery to muscle without requiring a significant shift in systemic ANGPTL4. For instance, exercise dramatically increases the translocation of FAT/CD36 and FABPpm FA transporters to the sarcolemma, enhancing direct FA uptake from the plasma pool independent of LPL activity. This could diminish the necessity for robust ANGPTL4 down regulation [27]. The regulation of ANGPTL4 is complex and influenced by other factors. It is strongly induced by fasting and PPAR agonists (e.g. fibrates) and suppressed by insulin. In the cited studies involving participants with obesity and type 2 diabetes (who often have insulin resistance), this hormonal milieu may blunt the exercise-induced regulation of ANGPTL4. Furthermore, the weight loss interventions (e.g. caloric restriction) can confound the pure exercise effect, as weight loss is known to influence ANGPTL4 levels [8].

In contrast to the previously cited null findings, several studies report a significant exercise-induced reduction in ANGPTL4 levels. Dastah and Babaei demonstrated that 12 weeks of water-based exercise led to a significant decrease in serum ANGPTL4 in obese women compared to a CG [19]. Similarly, Soori et al. found that 12 weeks of resistance training significantly reduced ANGPTL4 levels within a group of sedentary obese postmenopausal women [28]. These studies suggest that under specific conditions—such as certain exercise modalities (water-based, resistance) and in particular populations (postmenopausal women)—exercise can indeed modulate ANGPTL4 expression. The apparent contradiction between studies showing no change and those showing a significant decrease in ANGPTL4 post-exercise can be reconciled by examining the nuances of exercise modality, population physiology, and measurement timing. The studies by Dastah and Babaei (WE) [19] and Soori et al. [28] (resistance training) involved modalities that impose unique metabolic and hormonal demands. Resistance training, in particular, is a potent stimulator of muscle hypertrophy and anabolic hormones, like growth hormone and testosterone, which can influence lipid metabolism and ANGPTL4 expression [29]. WE, while aerobic, also provides constant resistance and may induce a different physiological stress profile compared to land-based running or cycling, potentially explaining the divergent findings [30]. The population in the Soori et al. [28] study is a critical factor. The decline in estrogen during menopause is associated with unfavorable shifts in lipid metabolism and adipose tissue distribution. Estrogen is known to influence ANGPTL4 expression [31]. Therefore, exercise in this population may have a more pronounced effect on correcting a dysregulated metabolic state, leading to a significant drop in ANGPTL4 that might not be as evident in eumenorrheic or male cohorts. The baseline metabolic health and adiposity of participants are crucial. It is hypothesized that exercise may have a more potent effect on lowering ANGPTL4 in individuals with higher initial levels or greater metabolic dysfunction [32]. The participants in the studies showing a decrease were obese, while other null-finding studies included overweight and obese individuals.

It has been reported that ANGPTL4 levels increase in resting muscles during exercise, subsequently reducing LPL activity. This mechanism appears to facilitate the preferential utilization of FAs derived from TG as fuel for active skeletal muscles [32]. Several factors are known to influence variations in ANGPTL4 levels, including advanced age—characterized by heightened inflammatory and oxidative states—BMI, shifts in the fat tissue to skeletal muscle distribution ratio, limited sample sizes in studies, and the observed impact of ANGPTL4 on short-term energy redistribution, which does not seem to manifest long-term effects [7]. In this context, the absence of increased ANGPTL4 levels in elderly individuals with metabolic syndrome may suggest favorable conditions for the reduction of liver fat accumulation and blood lipid levels, potentially achievable through both terrestrial and aquatic exercise interventions; however, additional research is necessary to validate this hypothesis.

In another part of the present study, balance performance was assessed. A significant difference was observed in the balance index with eyes open among the studied groups, but the results of the post hoc tests did not indicate a significant difference between the two time points before and after the exercises in the present groups. The results of intra-group mean comparisons showed that dynamic balance and balance with eyes open improved significantly in the exercise groups compared to the pre-test, whereas no significant changes were observed in the balance with eyes closed variable across the three groups.

In a study involving older women (n=63), participants were randomly assigned to one of three groups: Neuromuscular proprioceptive facilitation, Pilates, or a CG. An exercise program, comprising 50-minute sessions, was implemented three times per week over a duration of four weeks for both the neuromuscular facilitation and Pilates groups. The results indicated that the neuromuscular facilitation group exhibited a statistically significant reduction in most stability parameters assessed, alongside improvements in Borg balance scale scores, functional test outcomes, and timed up and go (TUG) test results compared to the CG [33].

Another study investigated the effects of integrated instability resistance training and cognitive training (IRCT) compared to isolated instability resistance training (IRT) among two groups of 18 women, focusing on balance, walking, muscle strength, and cognitive functions. The one-leg stand test with eyes closed was utilized to assess static balance, while the step test with eyes closed and the TUG test were employed for the evaluation of dynamic balance. The IRCT group demonstrated greater enhancements in dual cognitive abilities and motor skills in comparison to the IRT group. Both groups displayed improvements in walking ability [34].

A study was conducted to evaluate the long-term effects of a physical exercise program on balance and the fear of falling among elderly participants aged 60 years and older who exhibited balance issues. Participants engaged in a one-month physical exercise regimen. The FRT was utilized to assess balance, while the falls efficacy scale-international (FES-I) was employed to evaluate the fear of falling. The results indicated a significant difference in FRT and FES-I scores both before and after the intervention, as well as between pre-intervention measurements and those taken two years later. Notable improvements in balance and reductions in the fear of falling were observed one month and two years following the completion of the program [35].

In the present study, the significant improvement in eyes-open balance indicates that the exercise intervention successfully enhanced neuromuscular function and proprioceptive integration. However, the persistence of this improvement only when visual input was available suggests that participants continued to rely heavily on vision as their primary reference for stability. This is a common compensatory strategy, particularly in populations with underlying balance deficits, where vision is used to compensate for less reliable somatosensory or vestibular signals [36].

The exercise likely improved the capacity to utilize this visual information more effectively alongside strengthened motor outputs, leading to better performance in eyes-open conditions [37]. The lack of improvement in eyes-closed balance is particularly revealing. It suggests that the training stimulus was not sufficiently specific or intense to induce significant neuroplasticity within the somatosensory and vestibular systems independently. Closing the eyes removes the dominant visual reference and forces the brain to rely exclusively on proprioceptive and vestibular cues. The absence of change in this condition implies that the neural pathways dedicated to processing these non-visual signals did not undergo substantial adaptation [38]. In essence, the training enhanced the ability to use proprioception in a supported context (with vision) but not in an isolated one.

It appears that exercises conducted in both environments may serve as contributing factors to enhancements in balance with eyes open. Research suggests that a combination of strength and aerobic exercises represents the most effective strategy for concurrently improving neuromuscular and cardiovascular performance in elderly populations, thereby preserving functional capacity during the aging process. This combination is significant due to the distinct physiological effects each type of exercise has on the body. Adaptations resulting from strength training yield improvements in muscle strength and hypertrophy, neural adaptations, increased recruitment of motor units, higher firing rates of motor units, and enhanced neural excitability. Conversely, aerobic resistance training facilitates central and peripheral adaptations that enhance VO2max and the skeletal muscle’s capacity to generate energy through oxidative metabolism, without concurrently increasing muscle strength or hypertrophy [39].

With respect to the balance index assessed with eyes open, it can be concluded that enhancements in functional factors—including vestibular sense, proprioception, spatial perception, muscle strength, endurance, joint flexibility, and the central nervous system’s responses to precise stimuli [9]—have contributed to improvements in balance under these conditions as a result of exercise. However, the limitations of the present study include insufficient control over nutritional factors and ancillary activities, particularly within the CG, which may have impacted the results. Moreover, the measurement of serum ANGPTL4 rather than tissue-specific expression, and a relatively short intervention period. Serum level assessments may not have accurately reflected changes in muscle and fat tissue levels. Consequently, further research that addresses these considerations could yield more precise results. Nevertheless, the findings of this study advocate for the implementation of similar exercise programs, tailored to the conditions and physical capabilities of individuals in both land and water environments, with regard to achieving optimal improvements in balance and BMI—two significant physical and functional factors in this demographic.

Conclusion

An eight-week combined exercise program improves balance in elderly men with metabolic syndrome, regardless of the training environment. Water-based exercise appears to offer an additional benefit for reducing BMI. The serum concentration of ANGPTL4 was not significantly modulated by exercise in this population, highlighting the complexity of its regulation. Future studies with longer durations, controlled diets, and tissue-specific measurements are warranted to fully elucidate the impact of exercise on ANGPTL4 metabolism and future interventions must mandatorily include sensory-challenge components, such as performing exercises on unstable surfaces (foam pads, balance boards) with eyes closed. This is essential to force the nervous system to rely more heavily on vestibule-proprioceptive pathways and to induce specific neuroplasticity within these circuits, leading to genuine improvements in non-visual balance control.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hakim Sabzevari University, Sabzevar, Iran (Code: IR.HSU.REC.1402.001) and written informed consent was obtained from all, participants.

Funding

This study was extracted from doctoral dissertation of Arash Koujori, approved by Hakim Sabzevari University, Sabzevar, Iran.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, review & editing: Roya Askari; Investigation, writing the original draft and data analysis, data collection: Arash Koujori; Funding administration: Arash Koujori, Roya Askari; Supervition: Roya Askari ,Amir Hosein Haghighi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all participants for their time and effort.

References

The increasing prevalence of the elderly population, along with the associated health challenges faced by older individuals, represents a significant concern for the international community. Aging is often accompanied by physical frailty and a decline in cognitive function [1]. The demographic shift toward an aging global population is a critical factor contributing to the rising incidence of metabolic syndrome (MetS), as older adults frequently exhibit a combination of cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors that characterize this syndrome [2]. Key indicators of MetS include increased waist circumference, elevated fasting serum glucose levels, heightened serum triglyceride levels, hypertension, and decreased levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL). The diagnosis of MetS necessitates the presence of three or more of these specified criteria [3].

Several proteins are recognized as being exclusively or predominantly secreted by the liver, exerting a direct influence on energy metabolism. These proteins, referred to as hepatokines, are integral to the modulation of insulin resistance and the enhancement of metabolic variables in individuals with type 2 diabetes [4]. Angiopoietin-like proteins (ANGPTLs) are liver-derived factors that share structural similarities with angiopoietin. Notably, ANGPTLs 3, 4, and 8 are critical in the regulation of lipid metabolism, primarily functioning to inhibit the activity of lipoprotein lipase (LPL) in circulation through specific binding interactions [5, 6]. ANGPTL4 is predominantly released from the liver in response to exercise. Furthermore, weight gain has been associated with elevated serum levels of ANGPTL4, whereas weight loss correlates with a reduction in its levels among young and middle-aged adults [6]. Nevertheless, there is a paucity of information regarding the effects of exercise combined with weight loss on ANGPTL4 expression levels in skeletal muscle and serum among older adults with metabolic syndrome [7]. Recent studies also suggest that high systemic levels of ANGPTL4, often observed in inflammatory conditions and obesity, may contribute to muscle atrophy and reduced mitochondrial function by inducing insulin resistance and disrupting insulin signaling in muscle. This, in turn, can indirectly affect individuals’ balance [8].

Falls are recognized as a significant health issue among the aging population, with fall-related injuries—including fractures, disabilities, substantial financial burdens on governments and families, and mortality—being a primary concern for the World Health Organization (WHO). Consequently, the identification of risk factors and specific preventive strategies for falls among the elderly is of paramount importance [9]. Balance is a highly complex function that encompasses both musculoskeletal and nervous system components. Functional factors influencing balance include vision, hearing, vestibular sense, proprioception, spatial perception, environmental changes, muscular strength, endurance, joint flexibility, and the central nervous system’s response to specific stimuli [10]. Age-related physical and physiological changes are associated with diminished flexibility, agility, speed, and balance [11]. Reduced muscular strength and decreased efficiency of the cardiovascular-respiratory system with advancing age contribute to this phenomenon. Endurance and resistance training may help sustain cardiovascular-respiratory efficiency, enhance strength, and mitigate joint degeneration [12]. Aquatic exercise has been shown to be effective in maintaining and improving physical performance in healthy older adults [13]. Given that diabetic patients are susceptible to chronic complications, including peripheral neuropathy, and face an increased risk of injuries and foot lesions, water-based exercise or hydrotherapy can be particularly beneficial. When submerged, an individual experiences only 56% of his/her body weight, resulting in minimal joint pressure and a lower risk of injury. Additionally, exercising in water can enhance endurance and muscle tone by increasing pressure on the muscles [14].

However, given that access to water-based exercise may not be universally available and often necessitates costly equipment, it is important to understand the comparative effects of endurance and resistance training in both terrestrial and aquatic environments on inflammatory factors that influence the progression of metabolic syndrome indices and the maintenance of balance performance. This understanding can yield practical insights for this segment of the elderly population and healthcare professionals. Accordingly, this study assessed the impact of combined land-water exercises (WE) on ANGPTL4 expression and balance improvement in elderly patients with metabolic syndrome. It compared the differential effects of these exercises on physical performance metrics and ANGPTL4 modulation to identify optimal intervention strategies.

Materials and Methods

This quasi-experimental study utilized a pre-test/post-test design. Forty-five elderly men with MetS (defined by fasting blood sugar >100 mg/dL [15], triglycerides (TG)>150 mg/dL [16], waist circumference >90 cm) were recruited from the Toooba Clinic at Razi Hospital, Qaemshahr. Exclusion criteria were cardiovascular disease, hormonal disorders, kidney and liver diseases, recent surgery, smoking, changing the dose of medication from previous conditions, and any therapeutic intervention affecting laboratory results. Participants were selected through purposive and convenience sampling and were randomly divided into three groups (n=15 each): The WE group, the land exercise (LE) group, and the control group (CG) who maintained their usual daily activities using a computer-generated random number sequence. A questionnaire on daily calorie consumption and food type was completed by the subjects, and they were asked to adhere to their usual dietary routine during the research period.

The sample size for this study was calculated using G*Power software, version 3.1. An a priori power analysis was conducted for a repeated measures ANOVA (within-between interaction), based on the study’s primary outcome variable: The change in ANGPTL4 concentration. Drawing from previous studies on the effects of exercise training on ANGPTL4, a moderate effect size (f=0.25) was assumed. With the significance level (α) set at 0.05 and the desired statistical power set at 80% (β=0.20), the analysis revealed that a minimum of 14 participants per group was required. To account for a potential 10% attrition rate, we recruited a final sample of 15 participants per group.

The training program for the exercise groups consisted of three sessions per week for eight weeks (Tables 1 and 2). The elastic bands included colors, such as yellow (light), red (medium), green (heavy), blue (very heavy), black (special heavy), silver (very heavy), and gold (maximum) [17]. Considering the physiological reduction in muscular strength in the elderly and the physical capabilities of the participants, only three colors—red (medium), green (heavy), and blue (very heavy)—were used.

Initially, combined exercises were conducted, followed by a 10-minute active rest period, after which endurance exercises were performed. Exercise intensity was monitored using a Polar chest pulse monitor [18]. To determine the maximum heart rate (HRmax), the age-predicted formula from Fox and Haskell (220-age) was used. Blood samples were collected 24 hours prior to the first exercise session and 48 hours following the final session [19]. The serum obtained from these samples was utilized to measure serum ANGPTL4 levels. Measurements of serum ANGPTL4 levels were conducted using a human-specific Zallbio kit manufactured in Germany, which possesses a sensitivity of 3 ng/mL and employs the sandwich ELISA method [20]. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated using the formula weight (kg) divided by height (m²). Anthropometric indices were assessed utilizing a 3D scanning device (top genesis), manufactured in Iran, to evaluate height, weight, BMI, body fat percentage, and waist circumference (validity and reliability of 0.982) [21]. To assess balance performance indices, including static balance with eyes open and closed, as well as dynamic balance, established tests, such as the Sharpened Romberg test (reliability with eyes open: 0.90-0.91 and reliability with eyes closed: 0.76-0.77) [22] and the functional reach test (FRT) with a validity and reliability of 0.98 [23] were employed. To ensure blinding and reduce the use of subjective judgment, all members of the evaluation team (blood sampling and functional testing) with the exception of the principal investigator, were blinded to the group allocation of the participants.

To evaluate the normality of the data, the Shapiro-Wilk test was used, and to ensure the homogeneity of variances, the Levene’s test was used. Also, before performing repeated measures analysis of variance, the sphericity of the variance difference between the subject groups was evaluated using the Mauchly’s Sphericity test. Considering the results of the Shapiro-Wilk test and the normality of all data except for weight, data analysis using repeated measures ANOVA was used for normal data, and the Friedman test was used for weight. After confirming the normality of the data and before comparing between groups, the Levene’s test was used to ensure the homogeneity of variances. According to the results of the Levene’s test and homogeneity of variance for all data except for the blindfolded balance test, the Bonferroni test was used for other data and the Games-Howell test was used for the blindfolded balance test. A significance threshold of P<0.05 was considered for statistical analysis. To calculate the percentage change, the difference between the final value (post-test) and the initial value (pre-test) was calculated. This result was then divided by the initial value. Finally, the outcome was multiplied by 100 to obtain the percentage (Equation 1):

1. Percentage change=Pre-test mean(Post-test Mean−Pre-test Mean)×100

Results

At baseline, the Mean±SD values for the aquatic exercise, land-based exercise, and CGs, respectively, were as follows: Weight: 84.07±15.76 kg, 78.36±9.76 kg, and 83.32±12.73 kg; BMI: 28.46±4.87 kg/m², 26.25±2.78 kg/m², and 28.33±3.34 kg/m², and body fat percentage: 24.92±7.44%, 23.90±4.80%, and 27.76±6.90%.

The results of the descriptive statistics concerning the anthropometric characteristics are presented in Table 3. The percentage changes indicated a decrease in weight and body fat percentage in both exercise groups, as well as a decrease in BMI in the aquatic exercise group.

Considering that all indices, with the exception of weight, exhibited a normal distribution (P>0.05), the Games-Howell post-hoc test was employed to identify the specific locations of weight differences. The Levene’s test confirmed homogeneity in body composition variables (BMI and body fat percentage), ANGPTL4 levels, and performance assessments (static balance with eyes open and dynamic balance) (P>0.05). Consequently, when deemed necessary, the Bonferroni post-hoc test was applied (Table 4).

Based on the results presented in Table 5, it is evident that the interaction effect of time within the group for the ANGPTL4 variable (P=0.303) was not statistically significant. This finding suggests that there were no meaningful changes among the three groups examined.

In Table 6, the results of the comparison of mean introversion indicate that, despite the observed decrease in ANGPTL4 levels in the training groups and an increase in the CGs, no statistically significant difference was found among the three study groups.

According to the results of Table 7, in the assessment of static balance with eyes open, a statistically significant difference was identified among the study groups (P=0.01). The post-hoc test results did not show significant differences between the groups at the two time points, before and after the study; it appears that the timing of the changes differed from the post-test time. No differences were observed between the groups for the other indices (P>0.05). However, the results of the post-hoc tests did not reveal significant differences between the groups at the two time points measured, both prior to and following the intervention; it seems that the timing of the observed changes diverged from the post-test assessment. Furthermore, no significant differences were noted between the groups concerning the other indices (P=0.24).

Intra-group mean comparisons indicated that both dynamic balance and static balance with eyes open exhibited significant improvements in all three groups when compared to pre-test measurements (P<0.05) (Figure 1). However, the results of the post-hoc did not reveal significant differences between the groups at the two time points measured, both prior to and following the intervention; it appears that the timing of the observed changes diverged from the post-test assessment. Furthermore, no significant differences were noted between the groups concerning the other indices (P>0.05).

Graph 1 shows significant improvement in eyes-open balance in all groups from pre-test to post-test. The slopes of the different lines indicate that the rate of improvement varied across groups (significant interaction effect), with the first group (likely the land or water training group) likely improving the most (P=0.001). No significant change was observed in eyes-closed balance scores over time and between groups. This graph clearly demonstrates this lack of change (P>0.05). A significant improvement in dynamic balance scores was evident in all groups from pre-test to post-test (P=0.001). Although the group and interaction effects were not significant, the graph shows that all groups benefited from the intervention.

Discussion

The present study’s results, which indicated no statistically significant alterations in ANGPTL4 levels following exercise interventions, are consistent with the existing body of literature.

This finding aligns with that of Li et al. who reported no significant changes in serum or skeletal muscle ANGPTL4 levels following a six-month combined exercise and weight loss program in older adults with obesity. The authors attributed the lack of significant change to participants’ age, BMI, and the type of tissue analyzed, also noting the limitation of a small sample size [7]. Similarly, Banitalebi et al. found that neither sprint interval training (SIT) nor combined aerobic and resistance training (A+R) over 10 weeks induced significant changes in circulating ANGPTL4 levels in middle-aged overweight women with type 2 diabetes. Furthermore, changes in myokines were not correlated with improvements in body composition or metabolic profiles [24]. Further supporting this consensus, Karami et al. observed no significant differences in serum ANGPTL4 following an eight-week regimen of either high-intensity combined training or aerobic-only training in women with type 2 diabetes. They proposed that an exercise duration of less than three months may be insufficient to modulate the molecular mechanisms governing ANGPTL4 secretion via free fatty acid (FA) stimulation [25].

Collectively, these studies, including the present study, suggest that short- to medium-term exercise interventions (up to six months), across various modalities (aerobic, resistance, high-intensity interval, or combined), do not consistently elicit significant changes in ANGPTL4 levels in populations with obesity or type 2 diabetes. The response of this protein appears to be influenced by factors, such as intervention duration, participants’ demographics (age and BMI), and the specific tissue sampled. The consistent lack of change in ANGPTL4 following exercise, as highlighted in the summary, presents an intriguing physiological paradox. ANGPTL4 is a potent inhibitor of LPL, an enzyme crucial for hydrolyzing TG in circulating VLDL and chylomicrons for storage in adipose tissue or oxidation in muscle. During exercise, energy demand in skeletal muscle surges. A logical physiological adaptation would be to suppress ANGPTL4 to disinhibit LPL activity in muscle, thereby facilitating increased FA uptake and oxidation to meet energy needs. Concurrently, a potential increase in ANGPTL4 in adipose tissue could reduce LPL activity there, redirecting lipid flux away from storage and toward working muscle. This tissue-specific regulation is a central hypothesis in exercise metabolism [26]. The body’s energy regulation is highly redundant. Other pathways may compensate to ensure fuel delivery to muscle without requiring a significant shift in systemic ANGPTL4. For instance, exercise dramatically increases the translocation of FAT/CD36 and FABPpm FA transporters to the sarcolemma, enhancing direct FA uptake from the plasma pool independent of LPL activity. This could diminish the necessity for robust ANGPTL4 down regulation [27]. The regulation of ANGPTL4 is complex and influenced by other factors. It is strongly induced by fasting and PPAR agonists (e.g. fibrates) and suppressed by insulin. In the cited studies involving participants with obesity and type 2 diabetes (who often have insulin resistance), this hormonal milieu may blunt the exercise-induced regulation of ANGPTL4. Furthermore, the weight loss interventions (e.g. caloric restriction) can confound the pure exercise effect, as weight loss is known to influence ANGPTL4 levels [8].

In contrast to the previously cited null findings, several studies report a significant exercise-induced reduction in ANGPTL4 levels. Dastah and Babaei demonstrated that 12 weeks of water-based exercise led to a significant decrease in serum ANGPTL4 in obese women compared to a CG [19]. Similarly, Soori et al. found that 12 weeks of resistance training significantly reduced ANGPTL4 levels within a group of sedentary obese postmenopausal women [28]. These studies suggest that under specific conditions—such as certain exercise modalities (water-based, resistance) and in particular populations (postmenopausal women)—exercise can indeed modulate ANGPTL4 expression. The apparent contradiction between studies showing no change and those showing a significant decrease in ANGPTL4 post-exercise can be reconciled by examining the nuances of exercise modality, population physiology, and measurement timing. The studies by Dastah and Babaei (WE) [19] and Soori et al. [28] (resistance training) involved modalities that impose unique metabolic and hormonal demands. Resistance training, in particular, is a potent stimulator of muscle hypertrophy and anabolic hormones, like growth hormone and testosterone, which can influence lipid metabolism and ANGPTL4 expression [29]. WE, while aerobic, also provides constant resistance and may induce a different physiological stress profile compared to land-based running or cycling, potentially explaining the divergent findings [30]. The population in the Soori et al. [28] study is a critical factor. The decline in estrogen during menopause is associated with unfavorable shifts in lipid metabolism and adipose tissue distribution. Estrogen is known to influence ANGPTL4 expression [31]. Therefore, exercise in this population may have a more pronounced effect on correcting a dysregulated metabolic state, leading to a significant drop in ANGPTL4 that might not be as evident in eumenorrheic or male cohorts. The baseline metabolic health and adiposity of participants are crucial. It is hypothesized that exercise may have a more potent effect on lowering ANGPTL4 in individuals with higher initial levels or greater metabolic dysfunction [32]. The participants in the studies showing a decrease were obese, while other null-finding studies included overweight and obese individuals.

It has been reported that ANGPTL4 levels increase in resting muscles during exercise, subsequently reducing LPL activity. This mechanism appears to facilitate the preferential utilization of FAs derived from TG as fuel for active skeletal muscles [32]. Several factors are known to influence variations in ANGPTL4 levels, including advanced age—characterized by heightened inflammatory and oxidative states—BMI, shifts in the fat tissue to skeletal muscle distribution ratio, limited sample sizes in studies, and the observed impact of ANGPTL4 on short-term energy redistribution, which does not seem to manifest long-term effects [7]. In this context, the absence of increased ANGPTL4 levels in elderly individuals with metabolic syndrome may suggest favorable conditions for the reduction of liver fat accumulation and blood lipid levels, potentially achievable through both terrestrial and aquatic exercise interventions; however, additional research is necessary to validate this hypothesis.

In another part of the present study, balance performance was assessed. A significant difference was observed in the balance index with eyes open among the studied groups, but the results of the post hoc tests did not indicate a significant difference between the two time points before and after the exercises in the present groups. The results of intra-group mean comparisons showed that dynamic balance and balance with eyes open improved significantly in the exercise groups compared to the pre-test, whereas no significant changes were observed in the balance with eyes closed variable across the three groups.

In a study involving older women (n=63), participants were randomly assigned to one of three groups: Neuromuscular proprioceptive facilitation, Pilates, or a CG. An exercise program, comprising 50-minute sessions, was implemented three times per week over a duration of four weeks for both the neuromuscular facilitation and Pilates groups. The results indicated that the neuromuscular facilitation group exhibited a statistically significant reduction in most stability parameters assessed, alongside improvements in Borg balance scale scores, functional test outcomes, and timed up and go (TUG) test results compared to the CG [33].

Another study investigated the effects of integrated instability resistance training and cognitive training (IRCT) compared to isolated instability resistance training (IRT) among two groups of 18 women, focusing on balance, walking, muscle strength, and cognitive functions. The one-leg stand test with eyes closed was utilized to assess static balance, while the step test with eyes closed and the TUG test were employed for the evaluation of dynamic balance. The IRCT group demonstrated greater enhancements in dual cognitive abilities and motor skills in comparison to the IRT group. Both groups displayed improvements in walking ability [34].

A study was conducted to evaluate the long-term effects of a physical exercise program on balance and the fear of falling among elderly participants aged 60 years and older who exhibited balance issues. Participants engaged in a one-month physical exercise regimen. The FRT was utilized to assess balance, while the falls efficacy scale-international (FES-I) was employed to evaluate the fear of falling. The results indicated a significant difference in FRT and FES-I scores both before and after the intervention, as well as between pre-intervention measurements and those taken two years later. Notable improvements in balance and reductions in the fear of falling were observed one month and two years following the completion of the program [35].

In the present study, the significant improvement in eyes-open balance indicates that the exercise intervention successfully enhanced neuromuscular function and proprioceptive integration. However, the persistence of this improvement only when visual input was available suggests that participants continued to rely heavily on vision as their primary reference for stability. This is a common compensatory strategy, particularly in populations with underlying balance deficits, where vision is used to compensate for less reliable somatosensory or vestibular signals [36].

The exercise likely improved the capacity to utilize this visual information more effectively alongside strengthened motor outputs, leading to better performance in eyes-open conditions [37]. The lack of improvement in eyes-closed balance is particularly revealing. It suggests that the training stimulus was not sufficiently specific or intense to induce significant neuroplasticity within the somatosensory and vestibular systems independently. Closing the eyes removes the dominant visual reference and forces the brain to rely exclusively on proprioceptive and vestibular cues. The absence of change in this condition implies that the neural pathways dedicated to processing these non-visual signals did not undergo substantial adaptation [38]. In essence, the training enhanced the ability to use proprioception in a supported context (with vision) but not in an isolated one.

It appears that exercises conducted in both environments may serve as contributing factors to enhancements in balance with eyes open. Research suggests that a combination of strength and aerobic exercises represents the most effective strategy for concurrently improving neuromuscular and cardiovascular performance in elderly populations, thereby preserving functional capacity during the aging process. This combination is significant due to the distinct physiological effects each type of exercise has on the body. Adaptations resulting from strength training yield improvements in muscle strength and hypertrophy, neural adaptations, increased recruitment of motor units, higher firing rates of motor units, and enhanced neural excitability. Conversely, aerobic resistance training facilitates central and peripheral adaptations that enhance VO2max and the skeletal muscle’s capacity to generate energy through oxidative metabolism, without concurrently increasing muscle strength or hypertrophy [39].

With respect to the balance index assessed with eyes open, it can be concluded that enhancements in functional factors—including vestibular sense, proprioception, spatial perception, muscle strength, endurance, joint flexibility, and the central nervous system’s responses to precise stimuli [9]—have contributed to improvements in balance under these conditions as a result of exercise. However, the limitations of the present study include insufficient control over nutritional factors and ancillary activities, particularly within the CG, which may have impacted the results. Moreover, the measurement of serum ANGPTL4 rather than tissue-specific expression, and a relatively short intervention period. Serum level assessments may not have accurately reflected changes in muscle and fat tissue levels. Consequently, further research that addresses these considerations could yield more precise results. Nevertheless, the findings of this study advocate for the implementation of similar exercise programs, tailored to the conditions and physical capabilities of individuals in both land and water environments, with regard to achieving optimal improvements in balance and BMI—two significant physical and functional factors in this demographic.

Conclusion

An eight-week combined exercise program improves balance in elderly men with metabolic syndrome, regardless of the training environment. Water-based exercise appears to offer an additional benefit for reducing BMI. The serum concentration of ANGPTL4 was not significantly modulated by exercise in this population, highlighting the complexity of its regulation. Future studies with longer durations, controlled diets, and tissue-specific measurements are warranted to fully elucidate the impact of exercise on ANGPTL4 metabolism and future interventions must mandatorily include sensory-challenge components, such as performing exercises on unstable surfaces (foam pads, balance boards) with eyes closed. This is essential to force the nervous system to rely more heavily on vestibule-proprioceptive pathways and to induce specific neuroplasticity within these circuits, leading to genuine improvements in non-visual balance control.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hakim Sabzevari University, Sabzevar, Iran (Code: IR.HSU.REC.1402.001) and written informed consent was obtained from all, participants.

Funding

This study was extracted from doctoral dissertation of Arash Koujori, approved by Hakim Sabzevari University, Sabzevar, Iran.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, review & editing: Roya Askari; Investigation, writing the original draft and data analysis, data collection: Arash Koujori; Funding administration: Arash Koujori, Roya Askari; Supervition: Roya Askari ,Amir Hosein Haghighi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all participants for their time and effort.

References

- Li X, Zhang Y, Tian Y, Cheng Q, Gao Y, Gao M. Exercise interventions for older people with cognitive frailty-a scoping review. BMC Geriatrics 2022; 22(1):721. [DOI:10.1186/s12877-022-03370-3] [PMID]

- Dominguez LJ, Barbagallo M. The biology of the metabolic syndrome and aging. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care. 2016; 19(1):5-11. [DOI:10.1097/MCO.0000000000000243] [PMID]

- َAzali Alamdari K, Khodaei O. The effect of high intensity interval training on serum adiponectin, insulin resistance and markers of metabolic syndrome in men with metabolic syndrome. Journal of Applied Health Studies in Sport Physiology. 2018; 5(1):69-76. [DOI:10.22049/jassp.2019.26518.1196]

- Vizvari E, Abbas Zade HJMLJ. Effect of moderate aerobic exercise on serum levels of FGF21 and fetuin A in women with type 2 diabetes. Medical Laboratory Journal. 2020; 14(6):17-22. [DOI:10.52547/mlj.14.6.17]

- Barchetta I, Chiappetta C, Ceccarelli V, Cimini FA, Bertoccini L, Gaggini M, et al. Angiopoietin-like protein 4 overexpression in visceral adipose tissue from obese subjects with impaired glucose metabolism and relationship with lipoprotein lipase. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020; 21(19):7197. [DOI:10.3390/ijms21197197] [PMID]

- Barja‐Fernandez S, Moreno‐Navarrete JM, Folgueira C, Xifra G, Sabater M, Castelao C, et al. Plasma ANGPTL‐4 is associated with obesity and glucose tolerance: Cross‐sectional and longitudinal findings. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research. 2018; 62(10):1800060. [DOI:10.1002/mnfr.201800060] [PMID]

- Li G, Zhang H, Ryan ASJM. Skeletal muscle angiopoietin-like protein 4 and glucose metabolism in older adults after exercise and weight loss. Metabolites. 2020; 10(9):354. [DOI:10.3390/metabo10090354] [PMID]

- Kersten S. Role and mechanism of the action of angiopoietin-like protein ANGPTL4 in plasma lipid metabolism. Journal of Lipid Research. 2021; 62:100150. [DOI:10.1016/j.jlr.2021.100150] [PMID]

- Rajabi H, Sabouri M, Hatami EJCnE. Associations between physical activity levels with nutritional status, physical fitness and biochemical indicators in older adults. Clinical Nutrition ESPEN. 2021; 45:389-98. [DOI:10.1016/j.clnesp.2021.07.014] [PMID]

- Cui Z, Tang YY, Lee MH, Kim MKJM. The effects of gaze stability exercises on balance, gait ability, and fall efficacy in patients with chronic stroke: A 2-week follow-up from a randomized controlled trial. Medicine. 2024; 103(32):e39221. [DOI:10.1097/MD.0000000000039221] [PMID]

- Park JHJ. geriatrics. The effects of eyeball exercise on balance ability and falls efficacy of the elderly who have experienced a fall: A single-blind, randomized controlled trial. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2017; 68:181-5. [DOI:10.1016/j.archger.2016.10.006] [PMID]

- Leitão L, Venturini GR, Junior RP, Monteiro ER, Telles LG, Araújo G, et al. Impact of different resistance training protocols on balance, quality of life and physical activity level of older women. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(18):11765. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph191811765] [PMID]

- Waller B, Ogonowska-Słodownik A, Vitor M, Rodionova K, Lambeck J, Heinonen A, et al. The effect of aquatic exercise on physical functioning in the older adult: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Age and Ageing. 2016; 45(5):593-601. [DOI:10.1093/ageing/afw102] [PMID]

- Rees JL, Johnson ST, Boulé NGJAd. Aquatic exercise for adults with type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis. Acta Diabetologica. 2017; 54(10):895-904. [DOI:10.1007/s00592-017-1023-9] [PMID]

- Gradinaru D, Borsa C, Ionescu C, Margina D, Prada GI, Jansen EJAc, et al. Vitamin D status and oxidative stress markers in the elderly with impaired fasting glucose and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research. 2012; 24(6):595-602. [DOI:10.1007/BF03654842] [PMID]

- Assuncao N, Sudo FK, Drummond C, de Felice FG, Mattos P. Metabolic syndrome and cognitive decline in the elderly: A systematic review. Plos One. 2018; 13(3):e0194990. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0194990] [PMID]

- Andersen LL, Vinstrup J, Jakobsen MD, Sundstrup EJSjom, sports si. Validity and reliability of elastic resistance bands for measuring shoulder muscle strength. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports. 2017; 27(8):887-94. [DOI:10.1111/sms.12695] [PMID]

- Schubert MM, Clark A, De La Rosa AB. The Polar ® OH1 Optical Heart Rate Sensor is Valid during Moderate-Vigorous Exercise. Sports Medicine International Open. 2018; 2(3):E67-70. [DOI:10.1055/a-0631-0920] [PMID]

- Dastah S, Babaei S. [Effect of aquatic training on serum Fetuin-A, ANGPTL4 and FGF21 levels in type 2 diabetic obese women (Persian)]. Journal of Applied Health Studies in Sport Physiology. 2021; 8(2):51-60. [DOI:10.22049/jahssp.2021.27436.1390]

- Chang HC, Wang X, Gu X, Jiang S, Wang W, Wu T, et al. Correlation of serum VEGF-C, ANGPTL4, and activin A levels with frailty. Experimental Gerontology. 2024; 185:112345. [DOI:10.1016/j.exger.2023.112345] [PMID]

- Gharakhanlou BJ, Bonab SBJIJoDiDC. The effect of 12 weeks of training in water on serum levels of SIRT1 and FGF-21, glycemic index, and lipid profile in patients with type 2 diabetes. International Journal of Diabetes in Developing Countries. 2022; 42(4):727-34. [DOI:10.1007/s13410-021-01032-5]

- El-gohary TJIJHRS. Romberg test is a good indicator to reflect the performance of functional outcome measures among elderly: A Saudi experience along with simple biomechanical analysis. International Journal of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences. 2017; 6(4):192-9. [DOI:10.5455/ijhrs.0000000137]

- Różańska-Kirschke A, Kocur P, Wilk M, Dylewicz PJMR. The Fullerton Fitness Test as an index of fitness in the elderly. Medical Rehabilitation. 2006; 10:15-9. [Link]

- Banitalebi E, Kazemi A, Faramarzi M, Nasiri S, Haghighi MMJLs. Effects of sprint interval or combined aerobic and resistance training on myokines in overweight women with type 2 diabetes: A randomized controlled trial. Life Science. 2019; 217:101-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.lfs.2018.11.062] [PMID]

- Karami M, Ghafari M, Banitalebi E. Comparison of the effect of two personalized low volume-high intensity and combined (strength-aerobic) exercises on angiopoietin-like protein 4 (ANGPTL4) serum levels in women with type 2 diabetes: A short report. Journal of Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences. 2020; 19(1):97-106. [DOI:10.29252/jrums.19.1.97]

- Jia D, Zhang H, Liu T, Wang RJM. Exercise alleviates aging of adipose tissue through adipokine regulation. Metabolites. 2024; 14(3):135. [DOI:10.3390/metabo14030135] [PMID]

- Catoire M, Alex S, Paraskevopulos N, Mattijssen F, Evers-van Gogh I, Schaart G, et al. Fatty acid-inducible ANGPTL4 governs lipid metabolic response to exercise. Proceeding National Academy Science USA. 2014; 111(11):E1043-52. [DOI:10.1073/pnas.1400889111] [PMID]

- Soori R, Khosravi N, Mirshafiey SA, Gholijani F, Rezaeian N. [Effects of resistance training on angiopoietin-like protein 4 and lipids profile levels in postmenopausal obese women (Persian)]. Sport Physiology. 2018; 9(36):39-58. [DOI:10.22089/spj.2018.1974.1257]

- Tomeleri CM, Ribeiro AS, Nunes JP, Schoenfeld BJ, Souza MF, Schiavoni D, et al. Influence of resistance training exercise order on muscle strength, hypertrophy, and anabolic hormones in older women: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2020; 34(11):3103-9. [DOI:10.1519/JSC.0000000000003147] [PMID]

- Clemente-Suárez VJ, Fuentes-García JP, Fernandes RJ, Vilas-Boas JP. Psychological and physiological features associated with swimming performance. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(9):4561. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph18094561] [PMID]

- Deng M, Kersten S. Characterization of sexual dimorphism in ANGPTL4 levels and function. Journal of Lipid Research. 2024; 65(4):100526. [DOI:10.1016/j.jlr.2024.100526] [PMID]

- Hoffmann WG, Chen YQ, Schwartz CS, Barber JL, Dev PK, Reasons RJ, et al. Effects of exercise training on ANGPTL3/8 and ANGPTL4/8 and their associations with cardiometabolic traits. Journal of Lipid Research. 2024; 65(2):100495. [DOI:10.1016/j.jlr.2023.100495] [PMID]

- Mesquita LSdA, de Carvalho FT, Freire LSdA, Neto OP, Zângaro R. Effects of two exercise protocols on postural balance of elderly women: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatrics. 2015; 15(1):61. [DOI:10.1186/s12877-015-0059-3] [PMID]

- Wang Y, Zhang C, Wang B, Zhang D, Song X. Comparative effects of cognitive and instability resistance training versus instability resistance training on balance and cognition in elderly women. Scientific Reports. 2024; 14(1):26045. [DOI:10.1038/s41598-024-77536-x] [PMID]

- Perdamaian TKJJKM. Long-term effects of exercise on balance and fear of falling in community-dwelling elderly. Jurnal Kesehatan Masyarakat. 19(3):361-7. [DOI:10.15294/kemas.v19i3.44079]

- Smedes F, Heidmann M, Schäfer C, Fischer N, Stępień AJPTR. The proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation-concept; the state of the evidence, A narrative review. Physical Therapy Reviews. 2016; 21(1):17-31. [DOI:10.1080/10833196.2016.1216764]

- Africa EK, Van Deventer KJJECD, Care. A motor-skills programme to enhance visual motor integration of selected pre-school learners. Early Child Development and Care. 2017; 187(12):1960-70. [DOI:10.1080/03004430.2016.1201478]

- Qin W, Yu CJNp. Neural pathways conveying novisual information to the visual cortex. Neural plasticity. 2013; 2013(1):864920. [DOI:10.1155/2013/864920] [PMID]

- Zhang W, Liu X, Liu H, Zhang X, Song T, Gao B, et al. Effects of aerobic and combined aerobic-resistance exercise on motor function in sedentary older adults: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Back and Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation. 2024; 37(1):25-36. [DOI:10.3233/BMR-220414] [PMID]

Type of Study: Original Article |

Subject:

Health

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |