Volume 13, Issue 4 (Autumn 2025)

Iran J Health Sci 2025, 13(4): 319-328 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: IR.ZAUMS.REC. 1402.241 .

Clinical trials code: IR.ZAUMS.REC. 1402.241 .

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Izadirad H, Masoudy G, tamandani S. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Willingness Toward Organ Donation Among Adults in Southeast Iran. Iran J Health Sci 2025; 13 (4) :319-328

URL: http://jhs.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-1031-en.html

URL: http://jhs.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-1031-en.html

Health Promotion Research Center, Zahedan University of Medical Sciences, Zahedan, Iran. , remasoudy64@gmail.com

Full-Text [PDF 1057 kb]

(24 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (485 Views)

Full-Text: (5 Views)

Introduction

Organ donation is the act of removing healthy organs and tissues from a deceased or living donor for transplantation purposes to recipients who are experiencing organ failure [1]. The process of organ donation is fundamentally affected by factors, such as norms, values, and personal beliefs, and the shortage of organ donors is a critical global issue [2]. In Iran, despite being a leading transplant community in the Middle East [3-5], a significant gap persists between the supply of organs and patient demand. For instance, in 2019, there were over 12,000 patients on the transplant waiting list, but an average of fewer than 1,000 organ donations occur annually, leading to 7-10 daily deaths among those waiting [6]. While extensive research has addressed barriers in deceased donation, the challenges faced by living donors—whose complex decision-making is influenced by concerns related to personal life, family, employment, and the recipient [7] remain less studied, representing a significant research gap. A better understanding of the factors influencing organ donation could make a significant contribution to this issue, as a detailed understanding would allow them to be addressed and, consequently, organ donation would be more widespread [6]. Acceptance of organ donation is deeply shaped by cultural, ethnic, and religious factors [8], underscoring the vital role of public knowledge, attitudes, and willingness in the decision-making process [9].

Given the critical organ donation shortage in Southeastern Iran [2] and the high local prevalence of non-communicable diseases and road accidents in Khash City [10, 11], this study was designed to assess the knowledge, attitudes, and willingness regarding organ donation among adults in Khash. The findings will provide essential insights for healthcare policymakers, transplant organizations, and educational institutions to develop targeted strategies, educational programs, and policies aimed at increasing donor rates, addressing cultural barriers, and ultimately reducing waiting list mortality in this region and similar contexts.

Materials and Methods

Study setting and subjects

The present cross-sectional study was conducted over 4 months from June to September 2023 among adults in Khash city, after obtaining the ethics code from the Vice-Chancellor for Research of Zahedan University of Medical Sciences. Khash is located in Sistan and Baluchistan Province, in southeast Iran. The study population consisted of adult residents of Khash.

Sample size

Sample size calculation was conducted using G*Power software, version 3.1.9.7 [12]. The calculation was performed for the primary analysis using a linear multiple regression model (F-tests: Fixed model, R² deviation from zero), which was designed to identify factors associated with the willingness score. An effect size of f²=0.15, representing a small effect according to Cohen’s conventions [13], was chosen as a conservative estimate due to the exploratory nature of the study within this specific socio-cultural context and the absence of prior precise estimates in the target population, a standard significance level of α=0.05 was employed to maintain a 95% confidence level, consistent with conventional practice in biomedical and social science research [14, 15], and a statistical power of 1-β=0.99, exceeding the conventional 0.80 standard, was selected to maximize the probability of detecting true effects, minimize the risk of type II errors, and enhance the robustness of the findings, particularly given the anticipated small effect size and potential model complexity [14].

The following parameters were entered into G*Power, version 3.1.9.7 to calculate the sample size for the linear multiple regression (F-tests: Fixed model, R² deviation from zero): Effect size: 0.15, α error probability: 0.05, power (1-β error probability): 0.99, and number of predictors: 8. The analysis indicated a minimum required sample size of 395 participants. To account for potential non-response or incomplete questionnaires, the target sample size was set at 400.

Study setting

This cross-sectional study was conducted at four comprehensive urban health service centers in Khash city, selected as study sites. A total of 400 participants were recruited using a multi-center convenience sampling method. A predetermined quota of 100 participants was set for each center to ensure proportional representation. Participants were selected from the centers’ visitors based on the following inclusion criteria: 1) being a resident of Khash city, 2) age above 18 years, and 3) willingness to provide informed consent. Exclusion criteria comprised having a known psychological or mental health disorder (as documented in medical records or self-reported during recruitment) and submitting an incomplete questionnaire.

Sampling method

Despite the non-probability nature of convenience sampling, attempts were made to enhance the diversity of the sample. Recruitment was carried out at different times of the day and on different days of the week across all four centers to include individuals with varying ages, genders, and educational backgrounds.

Data collection tools

To collect data, a researcher-made questionnaire was used. This questionnaire consisted of two sections: demographic information and main questions assessing awareness, attitude, and willingness regarding organ donation. The demographic questions included age, gender, marital status, educational level, economic status, and occupation.

A structured self-administered questionnaire was developed based on an extensive literature review, comprising three distinct sections: (a) knowledge, which contained 11 items with response options of ‘true,’ ‘false,’ and ‘don’t know,’ where correct answers were scored 2 points, “don’t know” responses 1 point, and incorrect answers 0 points, yielding a total score range of 0–22; (b) attitude, which included 18 items measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “completely disagree” (0 points) to “completely agree” (4 points), with a total score range of 0–72; and © Willingness, which consisted of 6 items. “Yes” or “no” responses were scored 1 point if they represented the desired answer and 0 points if they did not, resulting in a total score range of 0–6.

Validity: Content validity was assessed by a panel of 8 experts specializing in health education (n=4), health psychology (n=1), Islamic studies (n=1), and transplant surgery (n=2). The content validity ratio (CVR) and content validity index (CVI) were calculated for each item and section. The final questionnaire achieved acceptable CVR and CVI scores, with section-specific results as follows: Knowledge (CVR=0.85, CVI=0.89), attitude (CVR=0.80, CVI=0.91), and willingness (CVR=0.83, CVI=0.86). Furthermore, construct validity was established through exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with Varimax rotation on a sample of 150 participants, which confirmed the anticipated three-factor structure.

Reliability: The reliability of the questionnaire was evaluated for each section separately. Internal consistency was measured using Cronbach’s α, and temporal stability was assessed via the test-re-test method with a two-week interval on a sub-sample of 30 participants. The results demonstrated good reliability across all sections: Knowledge section (α=0.81, test-re-test ICC=0.82), attitude section (α=0.87, test-re-test ICC=0.91), and willingness section (α=0.80, test-re-test ICC=0.79).

After obtaining the ethical code and an official letter, the research team visited the Khash Health Network and coordinated with four comprehensive urban health service centers. Eligible individuals were enrolled in the study following a detailed explanation of the research objectives and the acquisition of written informed consent. Data collection commenced thereafter. The questionnaire was self-administered by literate participants. For those who were illiterate or had limited education, it was administered orally by trained interviewers to ensure accurate data collection.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS software, version 22. Descriptive statistics, such as frequencies, percentages, Mean±SD, were employed to present demographic characteristics and the levels of awareness, attitudes, and willingness of participants regarding organ donation. To determine the factors influencing participants’ willingness to donate organs, a multiple linear regression analysis was performed. The assumptions of linear regression analysis were thoroughly assessed before interpreting the final model. The Durbin-Watson statistic was 1.92 (within the acceptable range of 1.5 to 2.5), indicating independence of residuals. Examination of residual plots (standardized residuals vs predicted values) revealed no clear patterns, confirming homoscedasticity and linearity. Furthermore, the normality of residuals was confirmed via the Shapiro-Wilk test and visual inspection of the Q-Q plot. No significant multicollinearity was detected, as all variance inflation factor (VIF) values were below 5. Based on these diagnostics, the model was deemed appropriate for the data. Statistical significance was considered at P<0.05.

Results

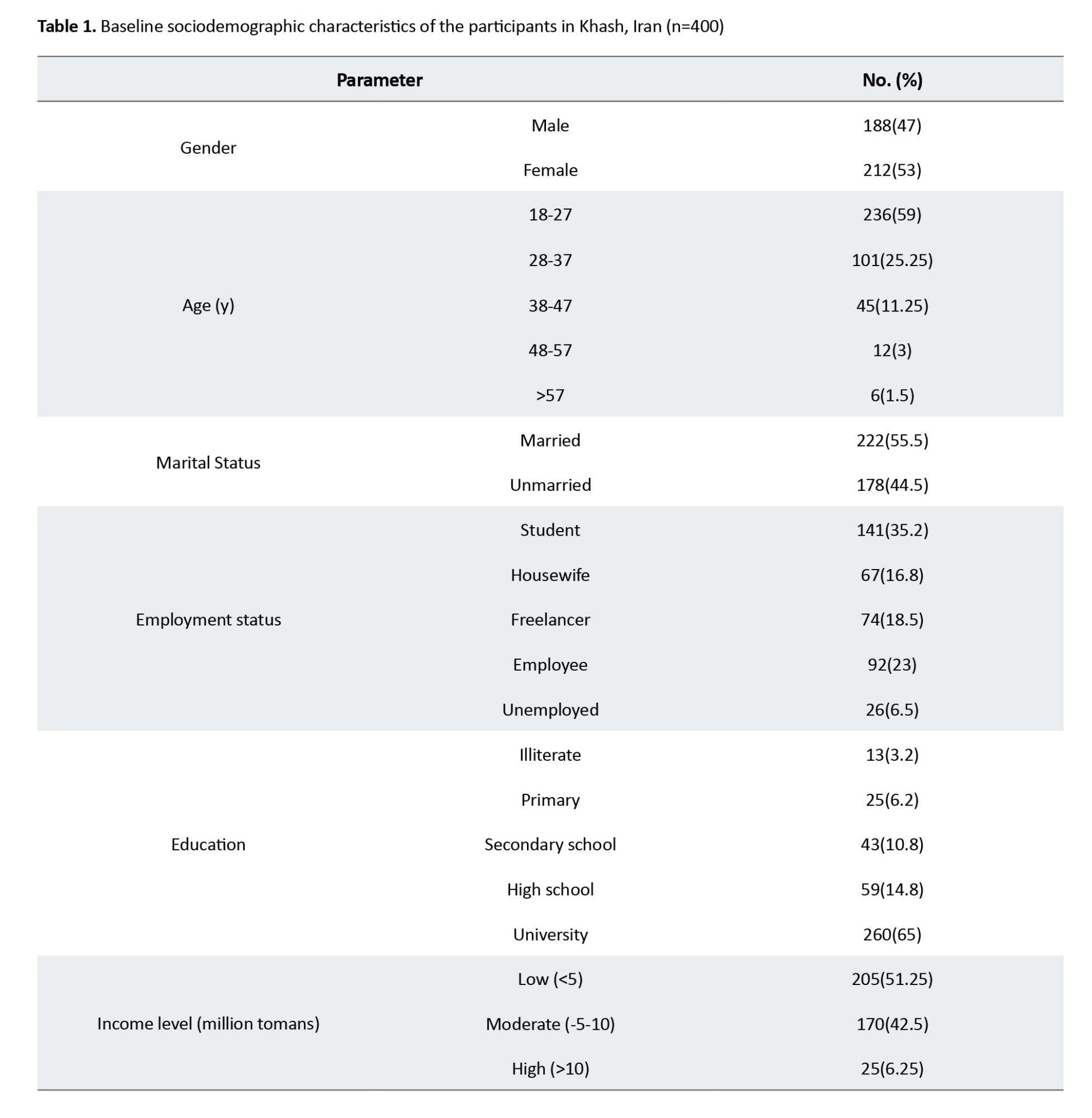

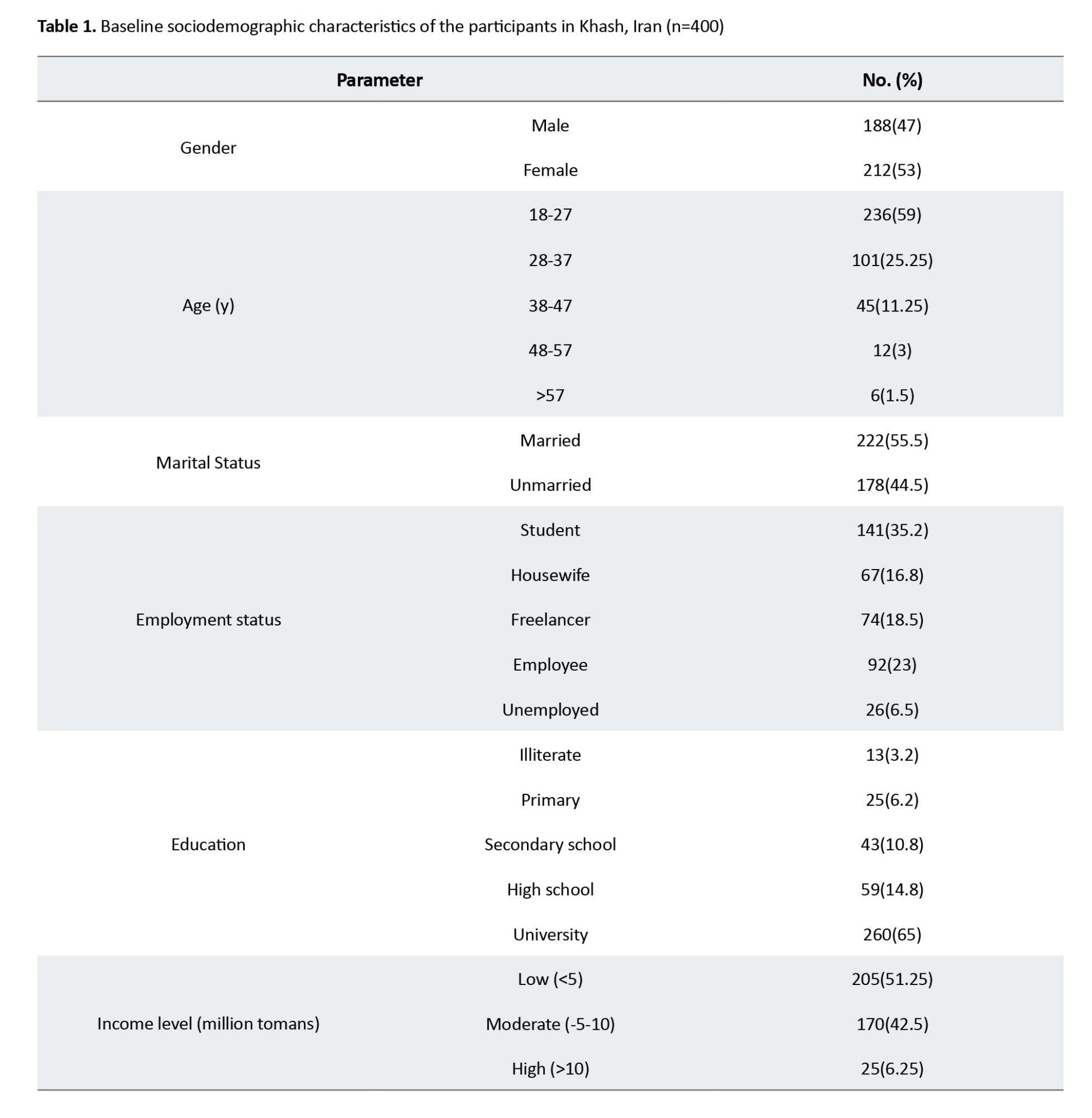

Out of 400 participants, 47% were male. The mean age of the participants was 28.39±9.07 years. A total of 55.5% of participants were married, and the 18–27 age group accounted for the highest frequency (Table 1). A significantly higher proportion of women (60.82%, n=163) expressed willingness compared to men (39.18%, n=105) (χ²=12.34, df=1, P=0.002).

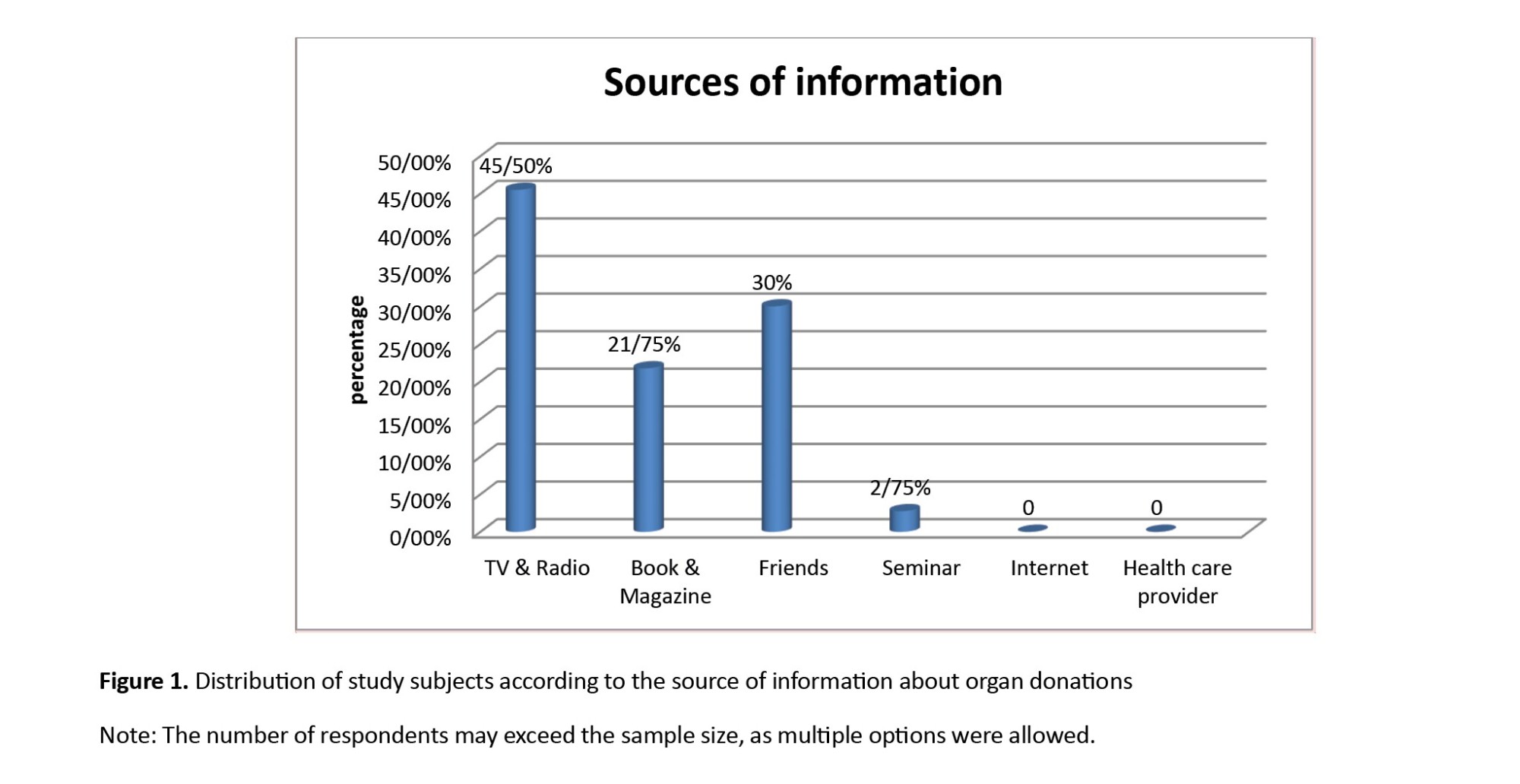

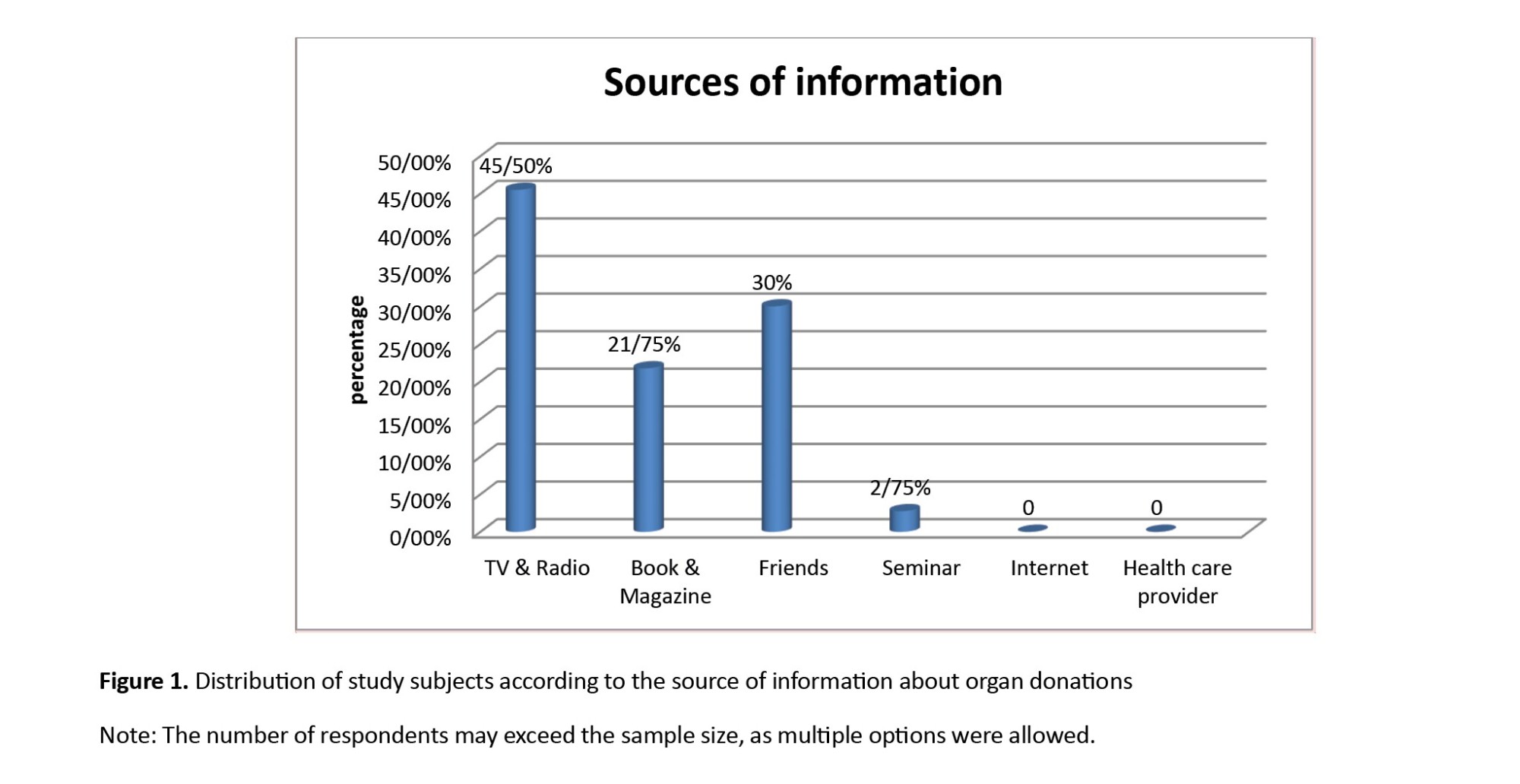

The primary sources of information regarding organ donation among the participants are presented in Figure 1.

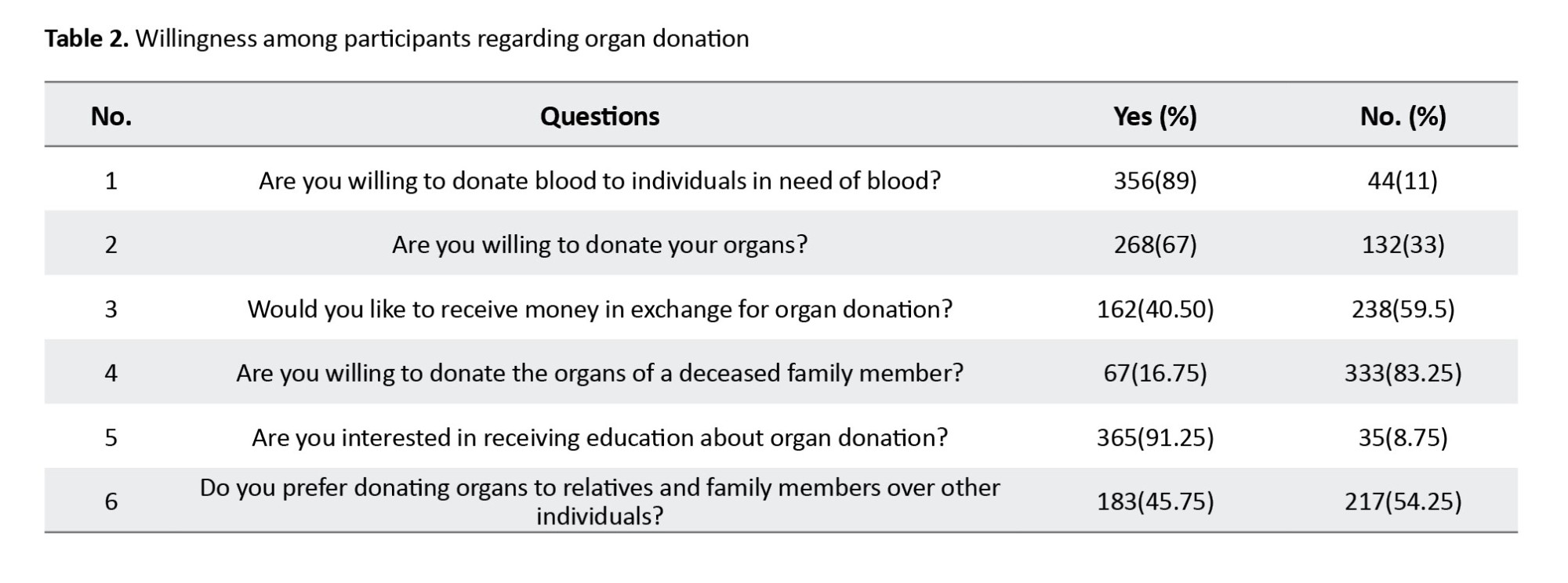

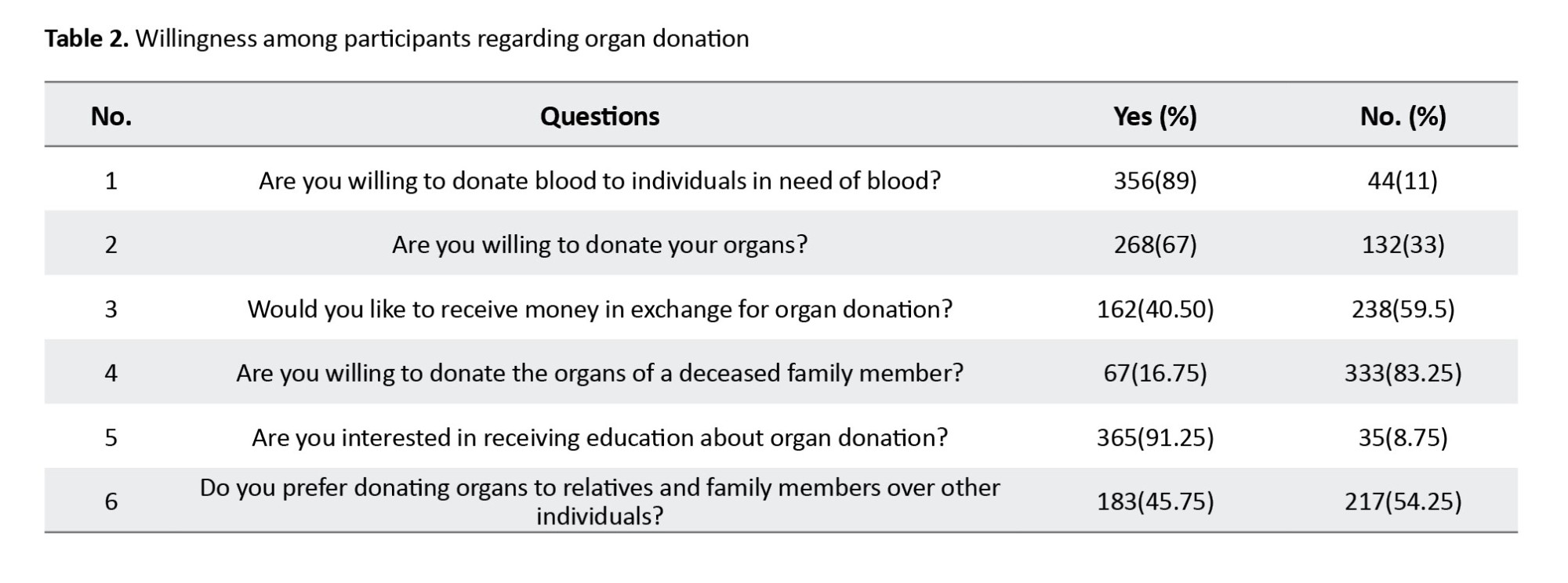

According to our findings, 67% of the participants were willing to donate their own organs, and 16.75% expressed a willingness to donate the organs of a deceased family member. Most of the individuals studied (59.50%) did not favor receiving money for organ donation. Additionally, 89% of the participants were willing to donate blood, and 91.25% were open to receiving education about organ donation (Table 2).

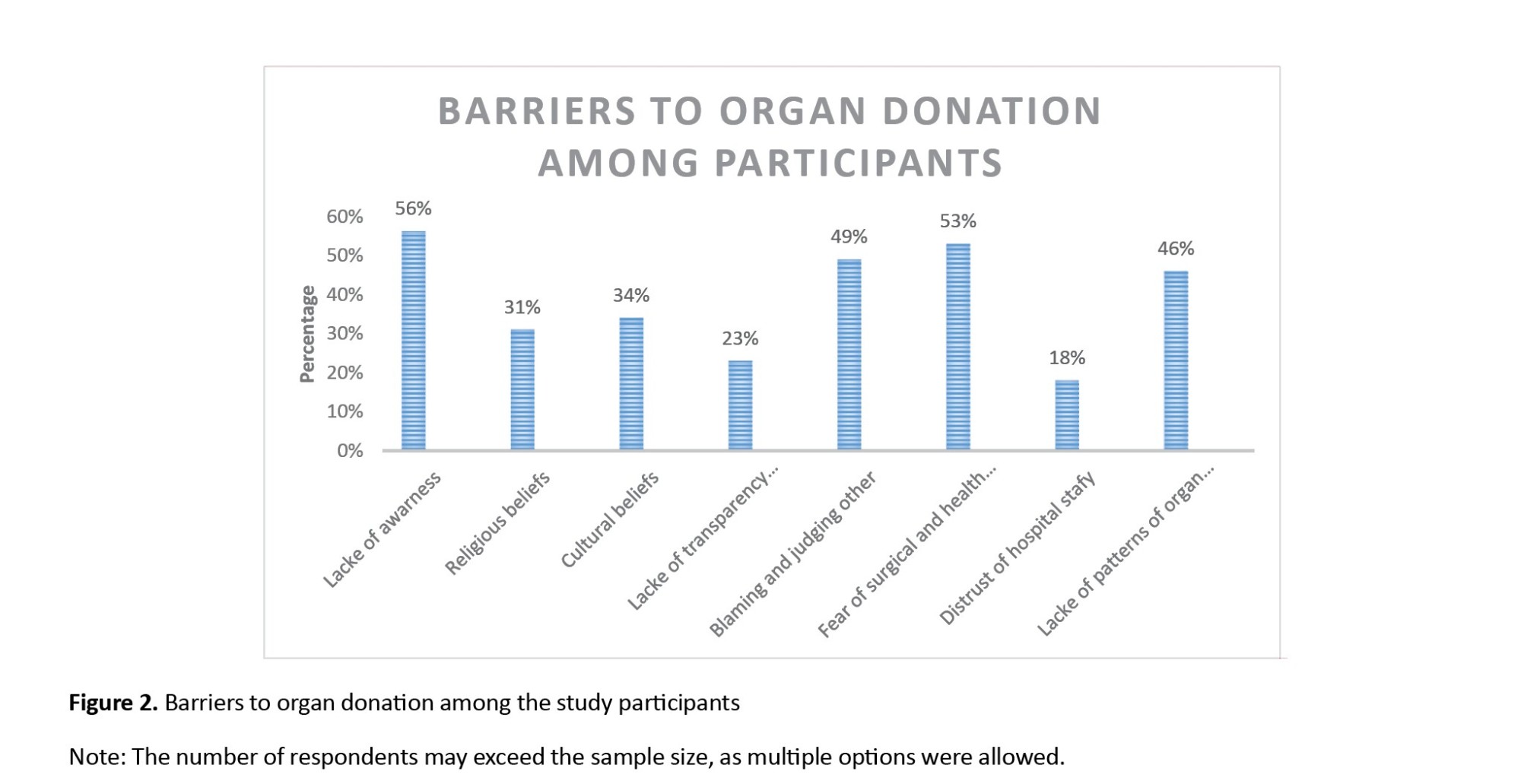

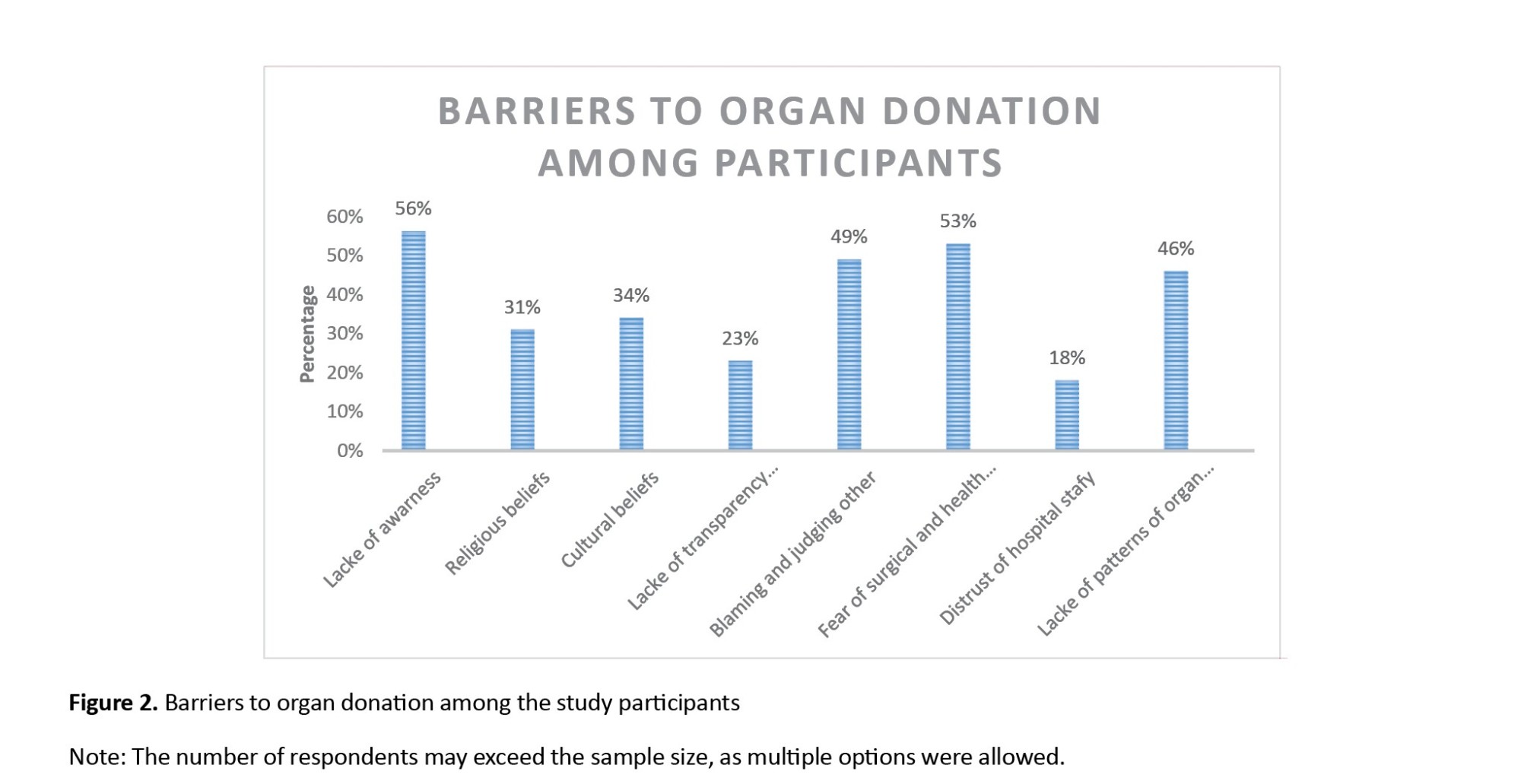

The most significant barriers to organ donation among the study participants are presented in Figure 2.

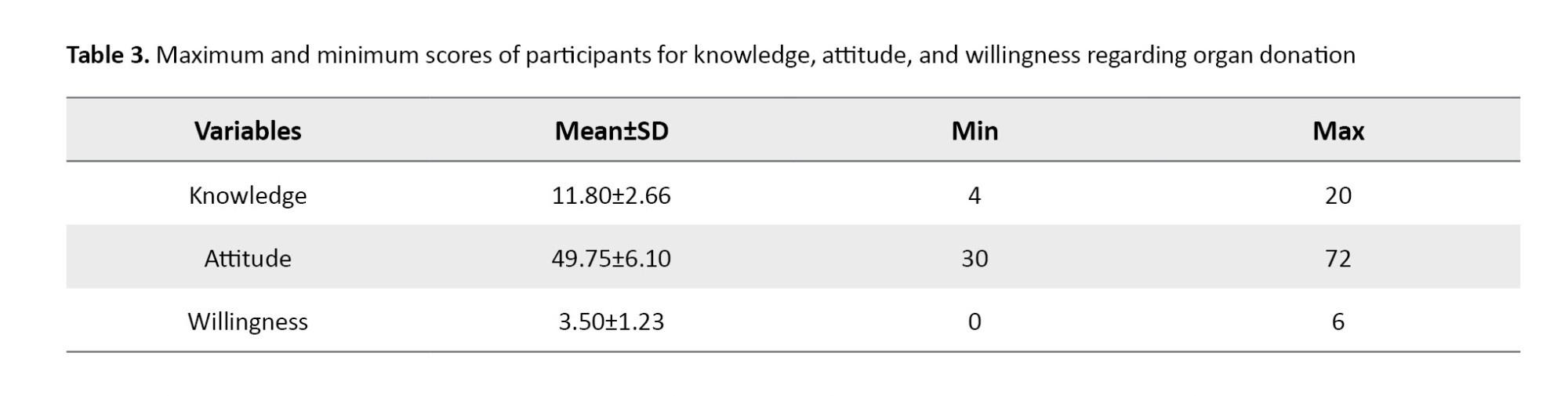

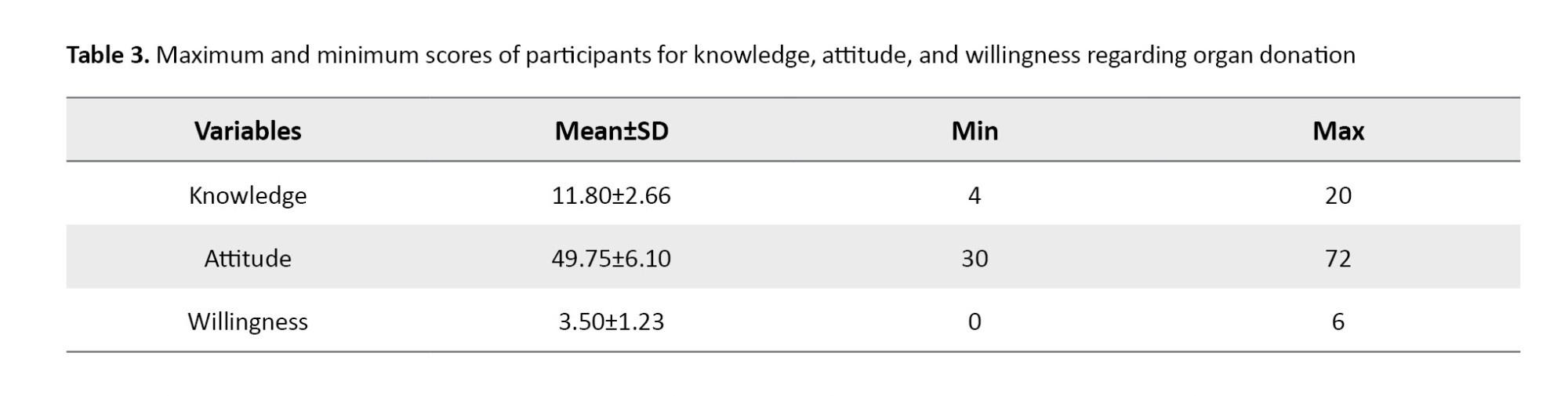

The mean knowledge score of participants regarding organ donation was 11.80 (out of a maximum possible score of 22). Detailed analysis revealed significant gaps in specific knowledge areas: Only 38 participants (9.5%) were aware that organ donation is possible from both living individuals and cadavers, and the knowledge of 382 participants (95.50%) regarding the religious ruling on organ donation was incorrect. In contrast, participants’ attitude and willingness scores were relatively higher, with mean scores of 49.75 (out of 72) and 3.50 (out of 6), respectively (Table 3).

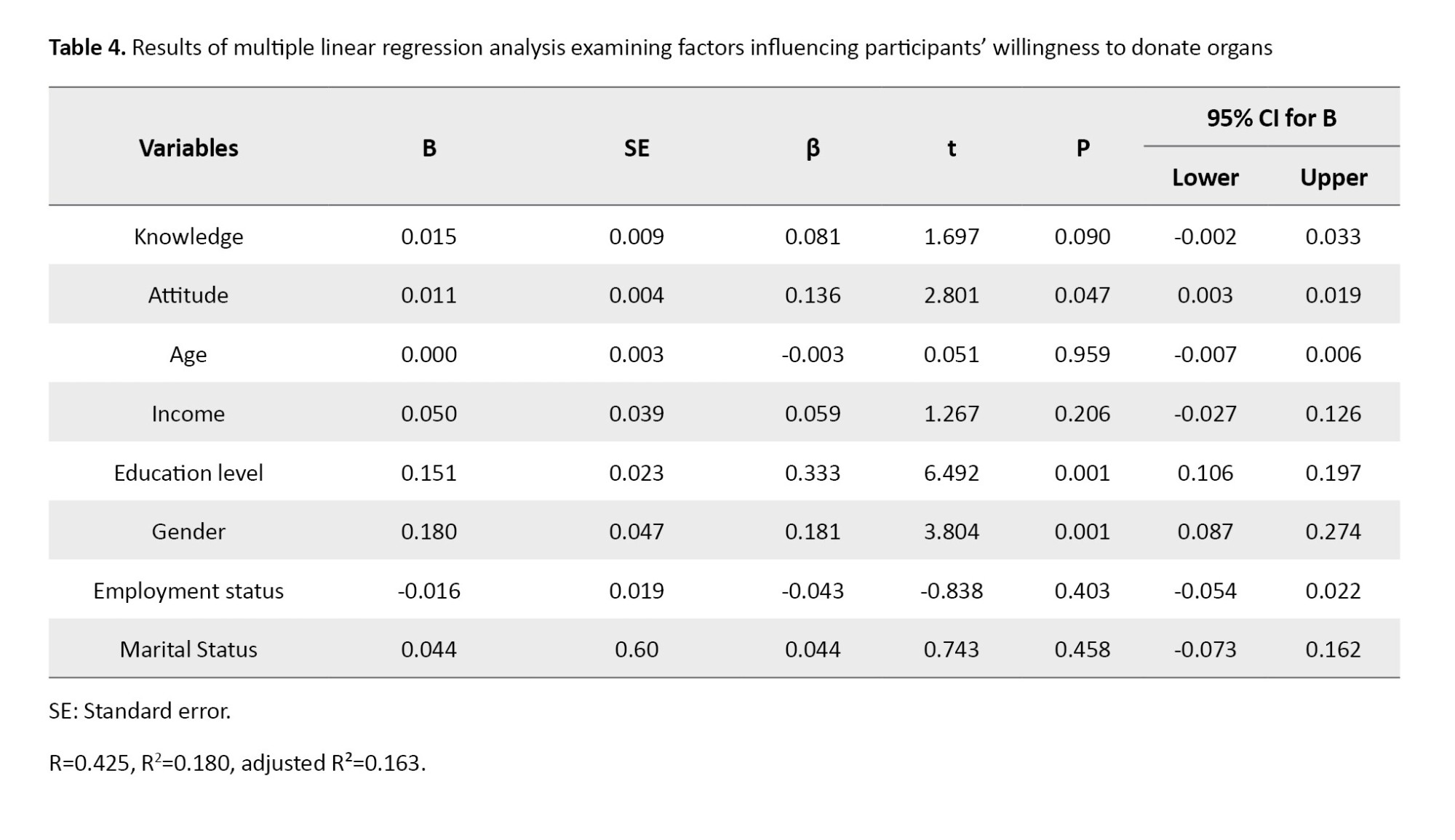

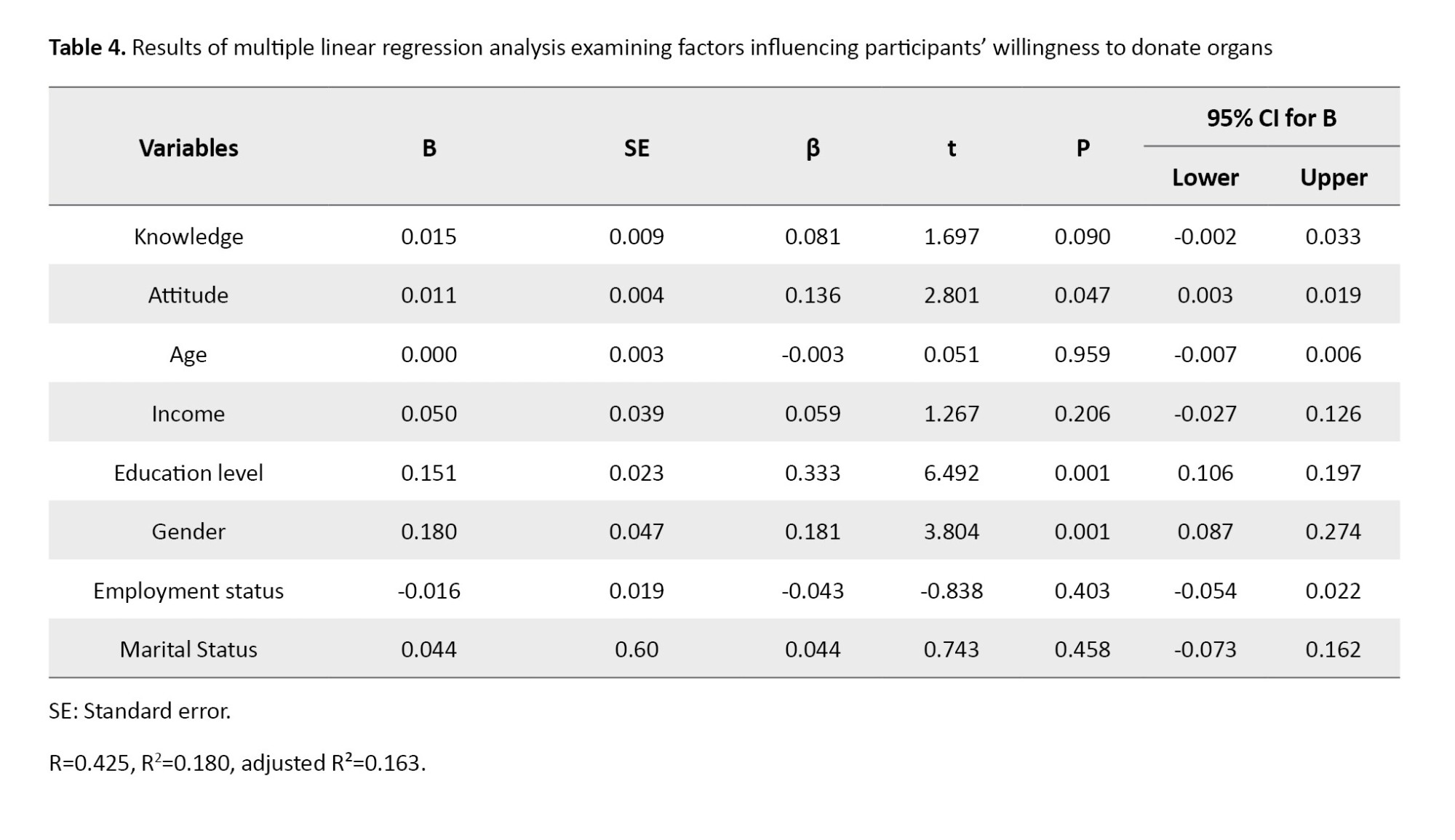

According to Table 4, awareness, attitudes, and demographic factors collectively predicted 18% of the variance in willingness to donate organs in the studied population. Among these factors, attitudes, education level, and gender had a significant impact on the willingness to donate organs.

Discussion

We aimed to investigate the status of knowledge, attitudes, and willingness toward organ donation among the adult population in Khash, Iran. Our analysis revealed a compelling set of findings. Organ donation and transplantation provide thousands of people a second chance at life and have become an indispensable part of advanced healthcare systems globally. Not only do transplant recipients benefit, but donor families and society as a whole also derive profound satisfaction from this humanitarian act.

Our study results indicated that the overall awareness about organ donation among adults in Khash, Iran, was measured at a mean score of 11.80 out of a maximum possible score of 22. This level is higher compared to the findings reported by Paul et al. [16] regarding Indian adults, who described the awareness level as unsatisfactory. This difference may stem from variations in cultural, religious, social, and value-based characteristics between the two populations, as well as differences in knowledge-assessment methodologies.

A substantial majority (67%) of participants expressed willingness to donate organs in the future, aligning with the findings by Shah [17] and Paul et al. [16] among students. This proportion was significantly higher than that reported among teachers in Sanandaj by Valiee et al. [18], where only 9.2% possessed an organ donation card compared to 19.8% in our sample. The observed disparity appears to stem from both cultural and social differences and more positive attitudes toward organ donation among Khash adults.

However, this stated intent often fails to materialize into concrete action due to numerous obstacles. Key barriers include limited awareness, apprehensions about surgery and social stigma, a lack of influential advocates, and deeply held religious or cultural views. The disparity is clearly quantified by the fact that less than 30% of those willing actually held an organ donation card.

The study found no significant association between awareness levels and willingness to donate organs. Despite this, organ donation appears familiar within the community, as evidenced by 19.8% of participants possessing donation cards and 10% reporting relatives who had undergone transplantation. Notably, 74.75% identified altruism as a critical motivating factor, a finding more favorable than those reported by Valiee et al. [18] among teachers and Van Buren et al. [19] among adults in the Netherlands.

On the other hand, the current study revealed that only 2% of the participants had a weak attitude toward organ donation. This contrasts with similar studies conducted in Saudi Arabia by Somaili et al. [20] and Khushaim et al. [21], which showed that 5.5% and 28% of participants, respectively, had negative attitudes toward organ donation. This discrepancy may be attributed to the strong altruistic attitudes of the current study’s participants toward organ donation, as well as their intense tribal and ethnic lifestyles and relationships.

Radio and television of the Islamic Republic of Iran emerged as the primary information sources, consistent with Valiee et al. [18] and Baghi et al. [22], though contrasting with Somaili et al. [20] where Internet and healthcare workers were predominant. This highlights both the effectiveness of mass media and the potential for utilizing additional channels, such as healthcare systems and digital platforms.

In the present study, more than two-thirds of the participants were willing to donate organs, which was higher than the results of the studies by Valiee et al. (57.6%) [18], Fan (47.45%) [23], a study from Northwest China (29.5%) [24], Japan (49.9%) [25], and the Middle East (49.8%) [5]. It is noteworthy that the results were somewhat similar to those of Tarzi et al. in Syria [26], where 62% of participants were willing to donate organs.

Our findings revealed no significant correlation between knowledge levels and willingness to donate organs. These results align with studies from the United Kingdom [27], Australia [28], Niger [29], and China [23], but contrast with Figueroa et al.’s findings [30], which reported a significant association. The observed discrepancies may stem from differences in knowledge assessment methods, cultural contexts, and socio-religious factors. Given that participants’ mean knowledge score represented approximately 50% of the total possible score, there remains substantial potential to enhance organ donation rates in southeastern Iran through improved educational initiatives. Further research is warranted to better understand the knowledge-willingness relationship in this cultural setting.

Our results demonstrated a significant positive association between attitudes toward organ donation and willingness to donate, consistent with the findings of Fontana et al. [31] and Fan et al. [23]. This suggests that interventions targeting attitude modification may effectively enhance donation willingness. The findings underscore the importance of implementing comprehensive educational strategies involving healthcare workers, applying evidence-based behavior change models, and utilizing digital platforms and social networks to foster positive attitudes and increase community participation in organ donation programs.

Approximately 41% of participants expressed acceptance of financial compensation for organ donation, aligning with findings by Gordon et al. [32] and Fan et al. [23]. This proportion markedly exceeds rates reported in comparable research in the Netherlands [19], suggesting that financial incentives may significantly influence donation willingness in the southeastern Iranian context. These results indicate the potential value of incorporating structured compensation mechanisms within ethical frameworks to enhance organ donation rates.

Gender emerged as a significant predictor of donation willingness, with attitudes showing a stronger correlation with willingness among women than men, consistent with the findings of Fan et al. [23] and Alghalyini et al. [33]. This gender effect may reflect socially constructed caregiving roles and heightened empathy, as 74.75% of participants cited altruism as their primary motivation. While education level also predicted willingness in our study—aligning with Alghalyini et al. [33]—this finding contrasts with that of Somaili et al. [20], highlighting the potential influence of cultural and methodological variables across contexts.

Conclusion

This study identified gender, education, and attitudes as key predictors of willingness toward organ donation among adults in southeastern Iran, with women and highly educated individuals demonstrating greater willingness, likely due to increased empathy, altruism, and health literacy. Despite generally positive attitudes, practical commitment remained low, as evidenced by the scarce number of actual organ donor cardholders, with major barriers, including limited public awareness, fear of medical outcomes, social stigma, and cultural-religious misconceptions. To address these challenges, we recommend implementing structured educational programs through primary healthcare centers, engaging religious and community leaders in awareness campaigns, and conducting further research to explore the ethical implications and potential role of regulated financial incentive models in this specific context. Ultimately, future efforts should focus on translating positive attitudes into actionable commitments through culturally sensitive interventions and policy improvements.

Limitations of the study

This study has several limitations that should be considered. The use of a non-standardized questionnaire, developed specifically for this study, may affect the validity and reliability of the measured constructs. While every effort was made to ensure content validity through literature review, the absence of established psychometric properties remains a constraint. Additionally, the convenience sampling method limits the generalizability of the findings to the broader population, as it may introduce selection bias and underrepresent certain demographic groups. The cross-sectional design precludes causal inferences, and self-reported data may be subject to social desirability bias. Lastly, the urban-focused sampling restricts the applicability of results to rural communities, where cultural and socioeconomic factors may differ significantly. Future studies should employ validated instruments, randomized sampling techniques, and mixed-methods approaches to address these limitations.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Zahedan University of Medical Sciences, Zahedan, iRAN (cODE:IR.ZAUMS.REC. 1402.241). Permission for data collection was granted with a formal letter from Zahedan University of Medical Sciences. The purpose and protocol of this study were explained, and participants signed informed written consent.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

Study design: Hossein Izadirad and Gholamreza Masoudy; Statistical analysis: Hossein Izadirad and Gholamreza Masoudy; Data collection: Gholamreza Masoudy and Somaye Tamandani; Reading and final approval: all authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors hereby extend their sincere gratitude and appreciation to all the respected participants in this study, whose dedication of time and sincere cooperation made this research possible.

References

Organ donation is the act of removing healthy organs and tissues from a deceased or living donor for transplantation purposes to recipients who are experiencing organ failure [1]. The process of organ donation is fundamentally affected by factors, such as norms, values, and personal beliefs, and the shortage of organ donors is a critical global issue [2]. In Iran, despite being a leading transplant community in the Middle East [3-5], a significant gap persists between the supply of organs and patient demand. For instance, in 2019, there were over 12,000 patients on the transplant waiting list, but an average of fewer than 1,000 organ donations occur annually, leading to 7-10 daily deaths among those waiting [6]. While extensive research has addressed barriers in deceased donation, the challenges faced by living donors—whose complex decision-making is influenced by concerns related to personal life, family, employment, and the recipient [7] remain less studied, representing a significant research gap. A better understanding of the factors influencing organ donation could make a significant contribution to this issue, as a detailed understanding would allow them to be addressed and, consequently, organ donation would be more widespread [6]. Acceptance of organ donation is deeply shaped by cultural, ethnic, and religious factors [8], underscoring the vital role of public knowledge, attitudes, and willingness in the decision-making process [9].

Given the critical organ donation shortage in Southeastern Iran [2] and the high local prevalence of non-communicable diseases and road accidents in Khash City [10, 11], this study was designed to assess the knowledge, attitudes, and willingness regarding organ donation among adults in Khash. The findings will provide essential insights for healthcare policymakers, transplant organizations, and educational institutions to develop targeted strategies, educational programs, and policies aimed at increasing donor rates, addressing cultural barriers, and ultimately reducing waiting list mortality in this region and similar contexts.

Materials and Methods

Study setting and subjects

The present cross-sectional study was conducted over 4 months from June to September 2023 among adults in Khash city, after obtaining the ethics code from the Vice-Chancellor for Research of Zahedan University of Medical Sciences. Khash is located in Sistan and Baluchistan Province, in southeast Iran. The study population consisted of adult residents of Khash.

Sample size

Sample size calculation was conducted using G*Power software, version 3.1.9.7 [12]. The calculation was performed for the primary analysis using a linear multiple regression model (F-tests: Fixed model, R² deviation from zero), which was designed to identify factors associated with the willingness score. An effect size of f²=0.15, representing a small effect according to Cohen’s conventions [13], was chosen as a conservative estimate due to the exploratory nature of the study within this specific socio-cultural context and the absence of prior precise estimates in the target population, a standard significance level of α=0.05 was employed to maintain a 95% confidence level, consistent with conventional practice in biomedical and social science research [14, 15], and a statistical power of 1-β=0.99, exceeding the conventional 0.80 standard, was selected to maximize the probability of detecting true effects, minimize the risk of type II errors, and enhance the robustness of the findings, particularly given the anticipated small effect size and potential model complexity [14].

The following parameters were entered into G*Power, version 3.1.9.7 to calculate the sample size for the linear multiple regression (F-tests: Fixed model, R² deviation from zero): Effect size: 0.15, α error probability: 0.05, power (1-β error probability): 0.99, and number of predictors: 8. The analysis indicated a minimum required sample size of 395 participants. To account for potential non-response or incomplete questionnaires, the target sample size was set at 400.

Study setting

This cross-sectional study was conducted at four comprehensive urban health service centers in Khash city, selected as study sites. A total of 400 participants were recruited using a multi-center convenience sampling method. A predetermined quota of 100 participants was set for each center to ensure proportional representation. Participants were selected from the centers’ visitors based on the following inclusion criteria: 1) being a resident of Khash city, 2) age above 18 years, and 3) willingness to provide informed consent. Exclusion criteria comprised having a known psychological or mental health disorder (as documented in medical records or self-reported during recruitment) and submitting an incomplete questionnaire.

Sampling method

Despite the non-probability nature of convenience sampling, attempts were made to enhance the diversity of the sample. Recruitment was carried out at different times of the day and on different days of the week across all four centers to include individuals with varying ages, genders, and educational backgrounds.

Data collection tools

To collect data, a researcher-made questionnaire was used. This questionnaire consisted of two sections: demographic information and main questions assessing awareness, attitude, and willingness regarding organ donation. The demographic questions included age, gender, marital status, educational level, economic status, and occupation.

A structured self-administered questionnaire was developed based on an extensive literature review, comprising three distinct sections: (a) knowledge, which contained 11 items with response options of ‘true,’ ‘false,’ and ‘don’t know,’ where correct answers were scored 2 points, “don’t know” responses 1 point, and incorrect answers 0 points, yielding a total score range of 0–22; (b) attitude, which included 18 items measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “completely disagree” (0 points) to “completely agree” (4 points), with a total score range of 0–72; and © Willingness, which consisted of 6 items. “Yes” or “no” responses were scored 1 point if they represented the desired answer and 0 points if they did not, resulting in a total score range of 0–6.

Validity: Content validity was assessed by a panel of 8 experts specializing in health education (n=4), health psychology (n=1), Islamic studies (n=1), and transplant surgery (n=2). The content validity ratio (CVR) and content validity index (CVI) were calculated for each item and section. The final questionnaire achieved acceptable CVR and CVI scores, with section-specific results as follows: Knowledge (CVR=0.85, CVI=0.89), attitude (CVR=0.80, CVI=0.91), and willingness (CVR=0.83, CVI=0.86). Furthermore, construct validity was established through exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with Varimax rotation on a sample of 150 participants, which confirmed the anticipated three-factor structure.

Reliability: The reliability of the questionnaire was evaluated for each section separately. Internal consistency was measured using Cronbach’s α, and temporal stability was assessed via the test-re-test method with a two-week interval on a sub-sample of 30 participants. The results demonstrated good reliability across all sections: Knowledge section (α=0.81, test-re-test ICC=0.82), attitude section (α=0.87, test-re-test ICC=0.91), and willingness section (α=0.80, test-re-test ICC=0.79).

After obtaining the ethical code and an official letter, the research team visited the Khash Health Network and coordinated with four comprehensive urban health service centers. Eligible individuals were enrolled in the study following a detailed explanation of the research objectives and the acquisition of written informed consent. Data collection commenced thereafter. The questionnaire was self-administered by literate participants. For those who were illiterate or had limited education, it was administered orally by trained interviewers to ensure accurate data collection.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS software, version 22. Descriptive statistics, such as frequencies, percentages, Mean±SD, were employed to present demographic characteristics and the levels of awareness, attitudes, and willingness of participants regarding organ donation. To determine the factors influencing participants’ willingness to donate organs, a multiple linear regression analysis was performed. The assumptions of linear regression analysis were thoroughly assessed before interpreting the final model. The Durbin-Watson statistic was 1.92 (within the acceptable range of 1.5 to 2.5), indicating independence of residuals. Examination of residual plots (standardized residuals vs predicted values) revealed no clear patterns, confirming homoscedasticity and linearity. Furthermore, the normality of residuals was confirmed via the Shapiro-Wilk test and visual inspection of the Q-Q plot. No significant multicollinearity was detected, as all variance inflation factor (VIF) values were below 5. Based on these diagnostics, the model was deemed appropriate for the data. Statistical significance was considered at P<0.05.

Results

Out of 400 participants, 47% were male. The mean age of the participants was 28.39±9.07 years. A total of 55.5% of participants were married, and the 18–27 age group accounted for the highest frequency (Table 1). A significantly higher proportion of women (60.82%, n=163) expressed willingness compared to men (39.18%, n=105) (χ²=12.34, df=1, P=0.002).

The primary sources of information regarding organ donation among the participants are presented in Figure 1.

According to our findings, 67% of the participants were willing to donate their own organs, and 16.75% expressed a willingness to donate the organs of a deceased family member. Most of the individuals studied (59.50%) did not favor receiving money for organ donation. Additionally, 89% of the participants were willing to donate blood, and 91.25% were open to receiving education about organ donation (Table 2).

The most significant barriers to organ donation among the study participants are presented in Figure 2.

The mean knowledge score of participants regarding organ donation was 11.80 (out of a maximum possible score of 22). Detailed analysis revealed significant gaps in specific knowledge areas: Only 38 participants (9.5%) were aware that organ donation is possible from both living individuals and cadavers, and the knowledge of 382 participants (95.50%) regarding the religious ruling on organ donation was incorrect. In contrast, participants’ attitude and willingness scores were relatively higher, with mean scores of 49.75 (out of 72) and 3.50 (out of 6), respectively (Table 3).

According to Table 4, awareness, attitudes, and demographic factors collectively predicted 18% of the variance in willingness to donate organs in the studied population. Among these factors, attitudes, education level, and gender had a significant impact on the willingness to donate organs.

Discussion

We aimed to investigate the status of knowledge, attitudes, and willingness toward organ donation among the adult population in Khash, Iran. Our analysis revealed a compelling set of findings. Organ donation and transplantation provide thousands of people a second chance at life and have become an indispensable part of advanced healthcare systems globally. Not only do transplant recipients benefit, but donor families and society as a whole also derive profound satisfaction from this humanitarian act.

Our study results indicated that the overall awareness about organ donation among adults in Khash, Iran, was measured at a mean score of 11.80 out of a maximum possible score of 22. This level is higher compared to the findings reported by Paul et al. [16] regarding Indian adults, who described the awareness level as unsatisfactory. This difference may stem from variations in cultural, religious, social, and value-based characteristics between the two populations, as well as differences in knowledge-assessment methodologies.

A substantial majority (67%) of participants expressed willingness to donate organs in the future, aligning with the findings by Shah [17] and Paul et al. [16] among students. This proportion was significantly higher than that reported among teachers in Sanandaj by Valiee et al. [18], where only 9.2% possessed an organ donation card compared to 19.8% in our sample. The observed disparity appears to stem from both cultural and social differences and more positive attitudes toward organ donation among Khash adults.

However, this stated intent often fails to materialize into concrete action due to numerous obstacles. Key barriers include limited awareness, apprehensions about surgery and social stigma, a lack of influential advocates, and deeply held religious or cultural views. The disparity is clearly quantified by the fact that less than 30% of those willing actually held an organ donation card.

The study found no significant association between awareness levels and willingness to donate organs. Despite this, organ donation appears familiar within the community, as evidenced by 19.8% of participants possessing donation cards and 10% reporting relatives who had undergone transplantation. Notably, 74.75% identified altruism as a critical motivating factor, a finding more favorable than those reported by Valiee et al. [18] among teachers and Van Buren et al. [19] among adults in the Netherlands.

On the other hand, the current study revealed that only 2% of the participants had a weak attitude toward organ donation. This contrasts with similar studies conducted in Saudi Arabia by Somaili et al. [20] and Khushaim et al. [21], which showed that 5.5% and 28% of participants, respectively, had negative attitudes toward organ donation. This discrepancy may be attributed to the strong altruistic attitudes of the current study’s participants toward organ donation, as well as their intense tribal and ethnic lifestyles and relationships.

Radio and television of the Islamic Republic of Iran emerged as the primary information sources, consistent with Valiee et al. [18] and Baghi et al. [22], though contrasting with Somaili et al. [20] where Internet and healthcare workers were predominant. This highlights both the effectiveness of mass media and the potential for utilizing additional channels, such as healthcare systems and digital platforms.

In the present study, more than two-thirds of the participants were willing to donate organs, which was higher than the results of the studies by Valiee et al. (57.6%) [18], Fan (47.45%) [23], a study from Northwest China (29.5%) [24], Japan (49.9%) [25], and the Middle East (49.8%) [5]. It is noteworthy that the results were somewhat similar to those of Tarzi et al. in Syria [26], where 62% of participants were willing to donate organs.

Our findings revealed no significant correlation between knowledge levels and willingness to donate organs. These results align with studies from the United Kingdom [27], Australia [28], Niger [29], and China [23], but contrast with Figueroa et al.’s findings [30], which reported a significant association. The observed discrepancies may stem from differences in knowledge assessment methods, cultural contexts, and socio-religious factors. Given that participants’ mean knowledge score represented approximately 50% of the total possible score, there remains substantial potential to enhance organ donation rates in southeastern Iran through improved educational initiatives. Further research is warranted to better understand the knowledge-willingness relationship in this cultural setting.

Our results demonstrated a significant positive association between attitudes toward organ donation and willingness to donate, consistent with the findings of Fontana et al. [31] and Fan et al. [23]. This suggests that interventions targeting attitude modification may effectively enhance donation willingness. The findings underscore the importance of implementing comprehensive educational strategies involving healthcare workers, applying evidence-based behavior change models, and utilizing digital platforms and social networks to foster positive attitudes and increase community participation in organ donation programs.

Approximately 41% of participants expressed acceptance of financial compensation for organ donation, aligning with findings by Gordon et al. [32] and Fan et al. [23]. This proportion markedly exceeds rates reported in comparable research in the Netherlands [19], suggesting that financial incentives may significantly influence donation willingness in the southeastern Iranian context. These results indicate the potential value of incorporating structured compensation mechanisms within ethical frameworks to enhance organ donation rates.

Gender emerged as a significant predictor of donation willingness, with attitudes showing a stronger correlation with willingness among women than men, consistent with the findings of Fan et al. [23] and Alghalyini et al. [33]. This gender effect may reflect socially constructed caregiving roles and heightened empathy, as 74.75% of participants cited altruism as their primary motivation. While education level also predicted willingness in our study—aligning with Alghalyini et al. [33]—this finding contrasts with that of Somaili et al. [20], highlighting the potential influence of cultural and methodological variables across contexts.

Conclusion

This study identified gender, education, and attitudes as key predictors of willingness toward organ donation among adults in southeastern Iran, with women and highly educated individuals demonstrating greater willingness, likely due to increased empathy, altruism, and health literacy. Despite generally positive attitudes, practical commitment remained low, as evidenced by the scarce number of actual organ donor cardholders, with major barriers, including limited public awareness, fear of medical outcomes, social stigma, and cultural-religious misconceptions. To address these challenges, we recommend implementing structured educational programs through primary healthcare centers, engaging religious and community leaders in awareness campaigns, and conducting further research to explore the ethical implications and potential role of regulated financial incentive models in this specific context. Ultimately, future efforts should focus on translating positive attitudes into actionable commitments through culturally sensitive interventions and policy improvements.

Limitations of the study

This study has several limitations that should be considered. The use of a non-standardized questionnaire, developed specifically for this study, may affect the validity and reliability of the measured constructs. While every effort was made to ensure content validity through literature review, the absence of established psychometric properties remains a constraint. Additionally, the convenience sampling method limits the generalizability of the findings to the broader population, as it may introduce selection bias and underrepresent certain demographic groups. The cross-sectional design precludes causal inferences, and self-reported data may be subject to social desirability bias. Lastly, the urban-focused sampling restricts the applicability of results to rural communities, where cultural and socioeconomic factors may differ significantly. Future studies should employ validated instruments, randomized sampling techniques, and mixed-methods approaches to address these limitations.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Zahedan University of Medical Sciences, Zahedan, iRAN (cODE:IR.ZAUMS.REC. 1402.241). Permission for data collection was granted with a formal letter from Zahedan University of Medical Sciences. The purpose and protocol of this study were explained, and participants signed informed written consent.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

Study design: Hossein Izadirad and Gholamreza Masoudy; Statistical analysis: Hossein Izadirad and Gholamreza Masoudy; Data collection: Gholamreza Masoudy and Somaye Tamandani; Reading and final approval: all authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors hereby extend their sincere gratitude and appreciation to all the respected participants in this study, whose dedication of time and sincere cooperation made this research possible.

References

- Moorlock G, Ives J, Draper H. Altruism in organ donation: An unnecessary requirement? Journal of Medical Ethics. 2014; 40(2):134-8. [DOI:10.1136/medethics-2012-100528]

- Rochelle TL, Ng JS. Examining behavioural intention towards organ donation in Hong Kong. Journal of Health Psychology. 2023; 28(1):17-29. [DOI:10.1177/13591053221092857] [PMID]

- Dhakate NN, Joshi R. Analysing process of organ donation and transplantation services in India at hospital level: SAP-LAP model. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management. 2020; 21(4):323-39. [DOI:10.1007/s40171-020-00251-9]

- Danaei G, Farzadfar F, Kelishadi R, Rashidian A, Rouhani OM, Ahmadnia S, et al. Iran in transition. The Lancet. 2019; 393(10184):1984-2005. [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)33197-0] [PMID]

- Mekkodathil A, El-Menyar A, Sathian B, Singh R, Al-Thani H. Knowledge and willingness for organ donation in the middle eastern region: A meta-analysis. Journal of Religion and Health. 2020; 59(1):1-14. [DOI:10.1007/s10943-019-00883-x] [PMID]

- Pourhosein E, Bagherpour F, Latif M, Pourhosein M, Pourmand G, Namdari F, et al. The influence of socioeconomic factors on deceased organ donation in Iran. Korean Journal of Transplantation. 2022; 36(1):54-60. [DOI:10.4285/kjt.21.0034] [PMID]

- Bahador RS, Farokhzadian J, Mangolian P, Nouhi E. Concerns and challenges of living donors when making decisions on organ donation: A qualitative study. Iranian Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Research. 2022; 27(2):149-56. [DOI:10.4103/ijnmr.ijnmr_158_21] [PMID]

- Farid MS, Mou TB. Religious, cultural and legal barriers to organ donation: The case of Bangladesh. Bangladesh Journal of Bioethics. 2021; 12(1):1-13. [DOI:10.3329/bioethics.v12i1.50654]

- Ruck JM, Rasmussen SE, Henderson ML, Massie AB, Segev DL. Interviews of living kidney donors to assess donation-related concerns and information-gathering practices. BMC Nephrology. 2018; 19(1):130. [DOI:10.1186/s12882-018-0935-0] [PMID]

- Taherian MR, Maleki F, Talebi M, Ainy E, Soori H, Ghadirzadeh MR, et al. Rising trend in traffic accident mortality in Iran after a decade of decline (2006-2022): Time to raise the alarm. BMC Public Health. 2025; 25(1):1808. [DOI:10.1186/s12889-025-22905-y] [PMID]

- Nozarian MH, Rajaie S, Karimi F. The intra-city/extra-city paradox in iran's road safety: Disparities in accident frequency and fatality rates. Science Journal Rescue and Relief. 2025; 17(4):217-27.

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods. 2007; 39(2):175-91. [DOI:10.3758/BF03193146] [PMID]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Link]

- Hulley SB, Cummings SR, Browner WS, Grady DG, Newman TB. Designing clinical research. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013. [Link]

- Pourhoseingholi MA, Vahedi M, Rahimzadeh M. Sample size calculation in medical studies. Gastroenterology and Hepatology from Bed to Bench. 2013; 6(1):14-7. [PMID]

- Paul S, Som TK, Saha I, Ghose G, Bera A, Singh A. Knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding organ donation among adult population of an urban field practice area of a medical college in durgapur, West Bengal, India. Indian Journal of Transplantation. 2019; 13(1):15-9. [DOI:10.4103/ijot.ijot_36_18]

- Shah R, Patel A, Ramanuj V, Solanki N. Knowledge and attitudes about organ donation among commerce college students. National Journal of Community Medicine. 2015; 6(4):533-5. [Link]

- Valiee S, Mohammadi S, Dehghani S, Khanpour F. Knowledge and attitude of teachers in Sanandaj city towards organ donation. Iranian Journal of Medical Ethics and History of Medicine. 2019; 12:14-28. [DOI:10.18502/npt.v6i2.912]

- Van Buren MC, Massey EK, Maasdam L, Zuidema WC, Hilhorst MT, IJzermans JN, et al. For love or money? Attitudes toward financial incentives among actual living kidney donors. American Journal of Transplantation. 2010; 10(11):2488-92. [DOI:10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03278.x] [PMID]

- Somaili M, Masmali A, Haqawi I, Al-Hulaibi M, AlHabji AA, Salami A, et al. Knowledge and attitude toward organ donation among the adult population in Jazan, Saudi Arabia. Cureus. 2022; 14(7):e27002. [DOI:10.7759/cureus.27002]

- Khushaim L, Al Ghamdi R, Al-Husayni F, Al-Zahrani A, Khan A, Al Zahrani A. The knowledge, perception and attitudes towards organ donation among general population-Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Advanced Research. 2018; 6(1):1255-69. [DOI:10.21474/IJAR01/6345]

- Baghi V, Dalvand S, Farajzadeh M, Nazari M, Ghanei Gheshlagh R. Evaluation of knowledge and attitude towards organ donation among the residents of Sanandaj City, iran. Iranian Journal of Rehabilitation Research in Nursing. 2017; 4(1):1-8. [Link]

- Fan X, Li M, Rolker H, Li Y, Du J, Wang D, et al. Knowledge, attitudes and willingness to organ donation among the general public: A cross-sectional survey in China. BMC Public Health. 2022; 22(1):918. [DOI:10.1186/s12889-022-13173-1] [PMID]

- Huang P, Luo A, Xie W, Xu Z, Li C. Factors influencing families' decision-making for organ donation in Hunan Province, China. Transplant Proceeding. 2019; 51(3):619-24. [DOI:10.1016/j.transproceed.2019.01.052] [PMID]

- Cabinet Office, Government of Japan. Cabinet office, government of Japan (2017) survey on organ transplantation (August 2017 survey). Tokyo: Cabinet Office; 2017. [Link]

- Tarzi M, Asaad M, Tarabishi J, Zayegh O, hamza R, Alhamid A, et al. Attitudes towards organ donation in Syria: A cross-sectional study. BMC Medical Ethics. 2020; 21(1):123. [DOI:10.1186/s12910-020-00565-4] [PMID]

- Wale J, Arthur A, Faull C. An analysis of knowledge and attitudes of hospice staff towards organ and tissue donation. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care. 2014; 4(1):98-103. [DOI:10.1136/bmjspcare-2012-000416] [PMID]

- Marck CH, Weiland TJ, Neate SL, Hickey BB, Jelinek GA. Australian emergency doctors’ and nurses’ acceptance and knowledge regarding brain death: A national survey. Clinical Transplantation. 2012; 26(3):E254-60. [DOI:10.1111/j.1399-0012.2012.01659.x] [PMID]

- Ibrahim M, Randhawa G. Knowledge, attitudes, and behavior of nigerian students toward organ donation. Transplantation Proceedings. 2017; 49(7):1691-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.transproceed.2017.04.011] [PMID]

- Figueroa CA, Mesfum ET, Acton NT, Kunst AE. Medical students’ knowledge and attitudes toward organ donation: Results of a Dutch survey. Transplantation Proceedings. 2013; 45(6):2093-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.transproceed.2013.02.135] [PMID]

- Fontana F, Massari M, Giovannini L, Alfano G, Cappelli G. Knowledge and attitudes toward organ donation in health care undergraduate students in Italy. Transplantation Proceedings. 2017; 49(9):1982-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.transproceed.2017.09.029] [PMID]

- Gordon EJ, Patel CH, Sohn MW, Hippen B, Sherman LA. Does financial compensation for living kidney donation change willingness to donate? American Journal of Transplantation. 2015; 15(1):265-73. [DOI:10.1111/ajt.13004] [PMID]

- Alghalyini B, Zaidi ARZ, Faroog Z, Khan MS, Ambia SR, Mahamud G, et al. Awareness and willingness towards organ donation among riyadh residents: A cross-sectional study. Healthcare. 2024; 12(14):1422. [DOI:10.3390/healthcare12141422] [PMID]

Type of Study: Original Article |

Subject:

Health

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |