Volume 13, Issue 4 (Autumn 2025)

Iran J Health Sci 2025, 13(4): 297-306 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: IR.ZAUMS.REC.1403.150

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Khosravi S, Yadegary M A, Aliabadi A, Arbabisarjou A, Ansari H. Relationship Between Depression and Daily Activities Among Older Adults in Zahedan, Iran, 2024. Iran J Health Sci 2025; 13 (4) :297-306

URL: http://jhs.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-1039-en.html

URL: http://jhs.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-1039-en.html

Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, Health Promotion Research Center, School of Health, Zahedan University of Medical Sciences, Zahedan, Iran. , Ansarih88@gmail.com

Keywords: Elderly, Depression, Activities of daily living (ADL), Instrumental activities of daily living (IADL)

Full-Text [PDF 898 kb]

(6 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (416 Views)

Full-Text: (3 Views)

Introduction

Aging is a natural, inevitable, gradual, and progressive process that encompasses the lives of all humans. At this stage of life, cell proliferation decreases and eventually stops [1]. Estimates show that the global population aged 65 and over will increase by 6% from 2022 to 2050, while the population aged 80 and over will increase by 283 million from 2019 to 2025 [2]. Iran is also facing an aging phenomenon due to demographic transition and declining birth rates, such that by 2050, the population aged 60 and over will reach 31% [3].

Given this growing trend, it is important to pay attention to the major problems of aging, including mental disorders, such as anxiety, depression, and stress [4]. Factors, such as chronic illnesses, the death of friends and acquaintances, physical weakness, decreased vision and hearing, inability to perform daily activities, and financial problems due to inability to work can cause or exacerbate emotions, such as stress, anxiety, sadness, hopelessness, and depression [5]. The prevalence of depression fluctuates across different regions due to a combination of factors, including varying risk factors, divergent study methodologies, dissimilar data collection instruments, and distinct geographical and population characteristics [6]. In a meta-analysis conducted in 2024, its rates in Africa, Europe, Australia and Asia was reported to be 26.3%, 12.3%, 27.8% and 28.3%, respectively [7]. According to a study by Jafari et al. in 2021, 52% of older adults experienced depression [8].

Physical functioning is a factor that can affect the mental health of older adults [9]. This index is used to assess the level of quality and health of life among older adults, which is measured and evaluated by concepts, such as activities of daily living (ADL) that refers to routine daily activities, such as eating, transportation, self-care, using the toilet, bathing, walking, climbing stairs, dressing and undressing, and controlling urination and defecation [10], and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), which include using the telephone, shopping, cooking, taking care of housework, doing laundry, taking medication, and controlling income and expenses. The conceptual framework distinguishes IADLs from ADLs by their engagement with more complex activities [11]. The inability to perform these activities can have detrimental effects, such as reduced quality of life and social participation, and is a risk factor for anxiety and depression [9]. Therefore, given the negative and significant correlation between performing these activities and multiple mental disorders [12], and given the importance of the health status of the elderly, there is a pressing need to understand these relationships in specific sociocultural contexts.

While previous studies have addressed different aspects of elderly well-being, there is a significant research gap in comprehensively examining depression and its multifaceted relationship with ADL and IADL, particularly among the elderly in Zahedan. Existing research may be limited due to its geographical scope, focus on only one type of activity (ADL or IADL), or failure to fully consider the unique demographic and socioeconomic factors prevalent in this particular region. Therefore, this study aimed to determine the relationship between depression and ADL and IADL among older adults in Zahedan in 2024. The innovation of this research lies in its comprehensive approach to examining these associated factors in a previously understudied population, thereby providing essential data for targeted health interventions and policies in the region. Specifically, this study sought to answer the following research questions: 1) What is the prevalence of depression among older adults in Zahedan? 2) Is there a significant relationship between depression and ADL among older adults in Zahedan? 3) Is there a significant relationship between depression and IADL among older adults in Zahedan? 4) Is there a significant relationship between depression and socio-demographic among older adults in Zahedan?

Materials and Methods

Type of study

The present study is cross-sectional and was conducted using a descriptive-analytical method.

Participants

The study population consisted of 324 older adults (aged 60 years and above) who were attendees at health centers located in Zahedan city.

Sampling method and sample size

Based on a reported prevalence of 22% for dependence in ADL in the study by Chauhan et al. [13], and considering a significance level of 0.05 and a maximum allowable error of 0.05, the minimum required sample size was calculated to be approximately 270 participants using the prevalence estimation formula [14]. Furthermore, accounting for the multi-stage cluster sampling method and incorporating a design effect of 1.2 to adjust for potential intra-cluster correlation, the final determined sample size was increased to 324 individuals.

The sampling method employed was multi-stage cluster sampling. Initially, the health and treatment centers in Zahedan city were considered as clusters (57 clusters). Subsequently, 8 clusters were selected using a simple random sampling method. These selected clusters demonstrated a relatively uniform distribution across different postal areas of the city. According to statistics from the Deputy of Health, there was no significant difference in the population covered by each cluster, and given the high intra-cluster correlation coefficient, it is believed that the sample selection from the clusters was without bias. Consequently, approximately 40 samples were selected from each cluster. On one or more consecutive days, visitors to the health and treatment centers were requested to introduce elderly individuals from their households who met the study’s inclusion criteria. Following their agreement and consent, the researcher visited the elderly individuals’ homes to complete the questionnaires. It is noteworthy that to ensure randomness in sample selection, the researcher randomly chose one day of the week to visit each health and treatment center. The data collection method involved face-to-face interviews, and the data collection tool was a written questionnaire. Data were collected via face-to-face interviews conducted by a trained interviewer with a master’s degree in epidemiology.

Instrument

The used questionnaire consisted of 4 parts. The first part, the socio-demographic questionnaire, included questions about age, gender, marital status, education level, physical activity, smoking, insurance coverage, and socioeconomic status. It should be noted that sufficient physical activity was defined as engaging in aerobic activity, such as walking for at least 30 minutes on 5 days a week. Smoking was also considered as follows: If the person did not smoke, he/she was classified in the never group; if the person smoked at least once a month, he/she was classified in the sometimes group; if the person smoked at least once a week, he/she was classified in the often group; and if the person smoked every day, he/she was classified in the always group. However, due to the small number of samples in the sometimes, often, and always groups, these groups were merged. Socioeconomic status was determined using variables, such as literacy level, occupation, and household assets (such as car, television, refrigerator, etc.) using the principal component analysis categorical principal component analysis (CAT PCA) method. Given that there is a correlation between these variables, to avoid collinearity in the model using the variables mentioned in the questionnaire, the subjects were classified into one of the levels of low, moderate, and high socioeconomic status based on the 33rd and 66th percentiles.

The second part, the ADL Questionnaire with the modified Barthel scale (10-item version) [15], was completed to assess the level of ability and independence in performing ADL for the desired samples. This tool includes 10 questions, including “eating”, “moving and commuting”, “going up and down stairs”, “changing clothes”, “bathing”, “defecating”, “moving and getting out of bed”, “personal hygiene”, “going to the bathroom” and “urinating”. The total score is 0-100. Dependency levels were categorized as follows: Scores of 0 to 66 indicated dependence, while scores of 67 to 100 indicated independence.

The third part, the IADL Questionnaire, is based on the Lawton and Brody [16] criteria. This questionnaire has 7 items: “Using the telephone”, “taking medication”, “preparing food”, “doing housework”, “shopping for necessities”, “using vehicles”, and “controlling income and expenditure”. The total score ranges from 0 to 14. Scores of 0 to 10 are classified as dependent and 11 to 14 as independent. In 2016, Taheri Tanjani et al. [17] found the sensitivity and specificity for ADL to be 0.75 and 0.96, respectively, and for IADL to be 0.71 and 0.77. They also reported that Cronbach’s α and intraclass correlation for both questionnaires were >0.75. Also, in the study by Mehraban et al. [18], it was found that the Lawton Scale has very good reliability and validity.

The fourth part, depression, was measured using the geriatric depression scale–15 (GDS-15). Yesavage and Sheikh [19] extracted this scale in 1986 from the 30-question version of the depression questionnaire. This questionnaire has 15 yes or no questions, and the classification of individuals is as follows: If an individual receives a score of less than 5, he/she is normal, a score of 5-9 indicates moderate depression, and a score of 10-15 indicates severe depression. In Iran, Malakouti et al. [20] reported their alpha coefficient and reliability as 0.96 and 0.85, respectively. Also, in the study by Soltaninejad et al. [21] in 2025, the GDS-15 was used to measure depression. The Persian version of this questionnaire had very high reliability, with Cronbach’s α of 0.94 and ICC of 0.92.

To confirm the reliability of the questionnaires, a pilot study was conducted with 30 older adults. The cronbach’s α coefficients for the ADL questionnaire, IADLquestionnaire, and GDS-15 were 0.90, 0.83, and 0.87, respectively.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria included individuals aged 60 years and older, willingness of the elderly to cooperate in the study, ability to communicate verbally, non-dependence of the elderly on bed rest, and absence of Alzheimer’s disease. The exclusion criteria included failure to complete some parts of the questionnaire. Depression status was not an inclusion or exclusion criterion; rather, depression levels were measured as a primary variable of interest in all participants.

Data analysis method

In the analyses of this study, STATA software, version 17 was utilized. To examine the normality of quantitative data, the Shapiro–Wilk test was used, and the data were presented as Mean±SD or frequency (percentage). The chi-square test, Pearson correlation coefficient, and regression analysis were used to examine the relationship and correlation between variables. The significance level for all statistical analyses was set at P<0.05.

Ethical consideration

Prior to data collection, all participants provided written informed consent, thereby ensuring their voluntary involvement and comprehensive understanding of the study’s nature and procedures. Participants were explicitly informed of their right to refuse participation or withdraw at any point without penalty, and their decisions were fully respected. Confidentiality was strictly maintained for all collected data. No compensation was provided to avoid any undue influence on participation, thus upholding the impartiality and accuracy of the data. The informed consent process also ensured participants understood their rights regarding personal data processing and their ability to object or withdraw consent at any stage, reinforcing their control over their information and privacy.

Results

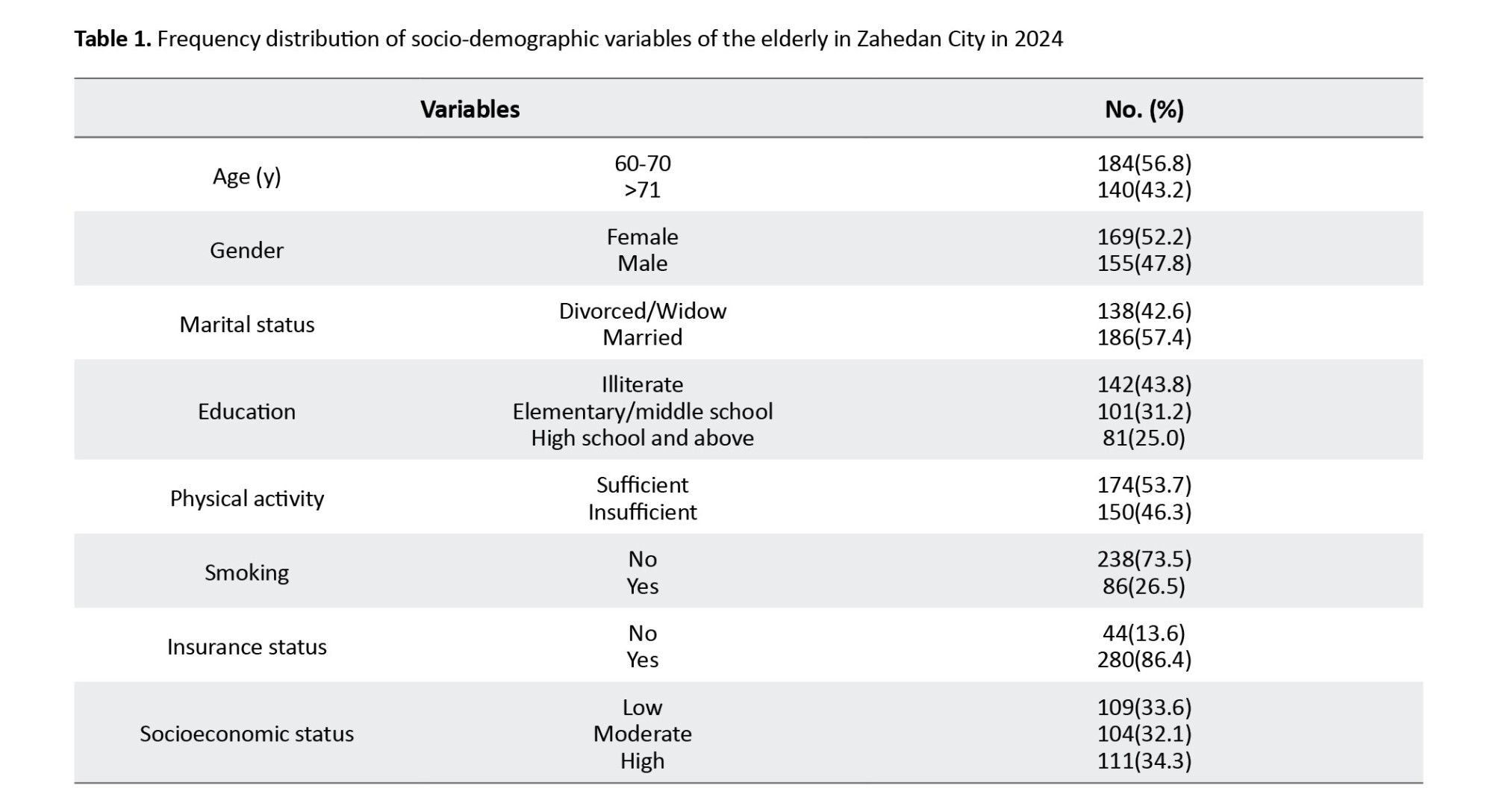

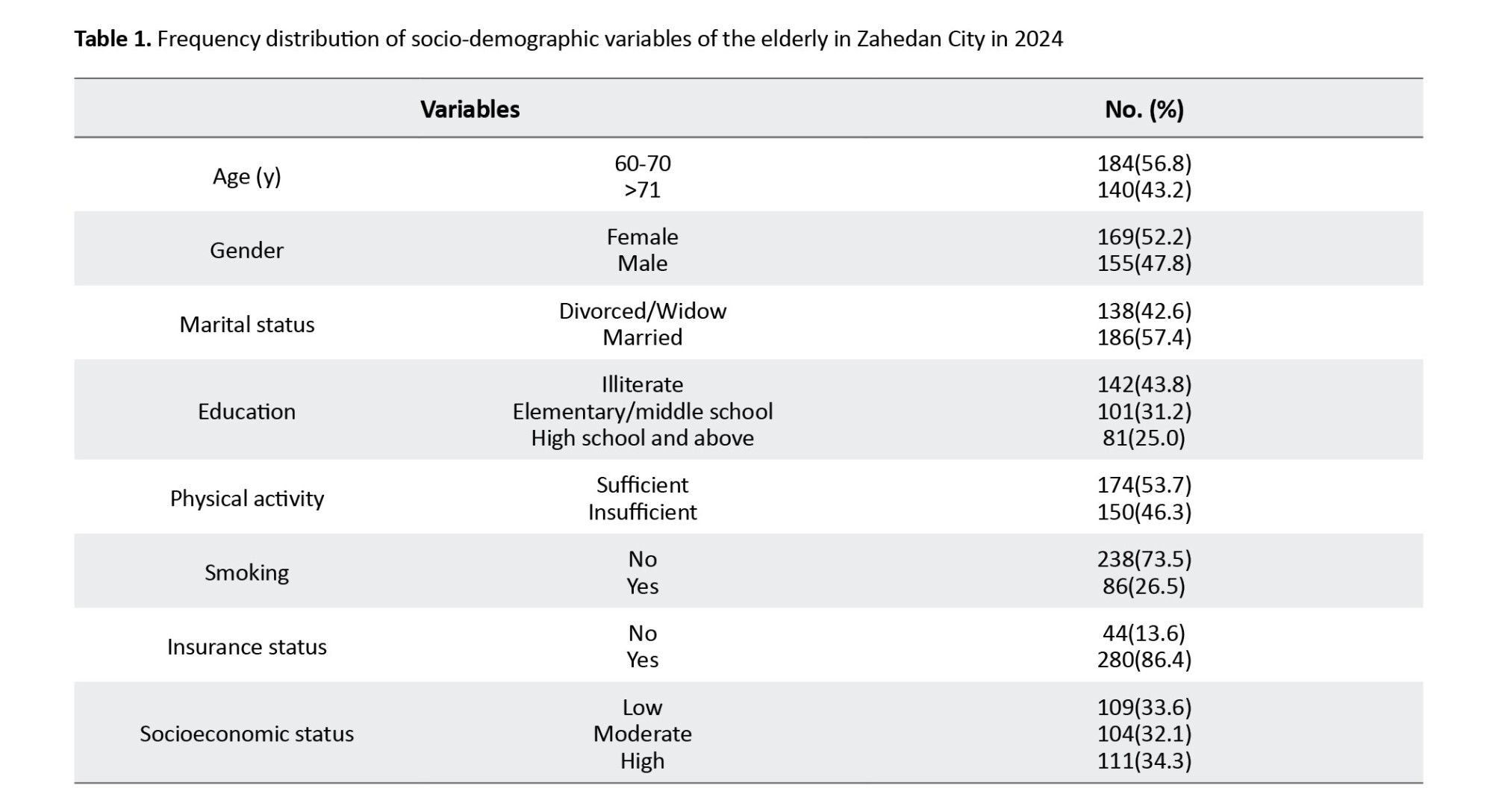

The mean age of the participants in this study was 70.84±18.8 with an age range of 60 to 99 years. In terms of age frequency distribution, 184 participants (56.8%) were between 60 and 70 years, and 140(43.2%) were 71 years and older. Also, 169 participants (52.2%) were female. In terms of marital status, 186 cases (57.4%) were married, and the rest of the older adults were widowed or divorced. In terms of education level, 142 cases (43.8%) were illiterate, 101(31.2%) had completed elementary and middle school, while the others were in high school or above. Regarding physical activity, 174 subjects (53.7%) were physically active. Also, in terms of smoking, 238 subjects (73.5%) did not smoke, and regarding insurance coverage, 280 subjects (86.4%) had insurance. Furthermore, 111 participants (34.3%) belonged to the high socioeconomic status category (Table 1).

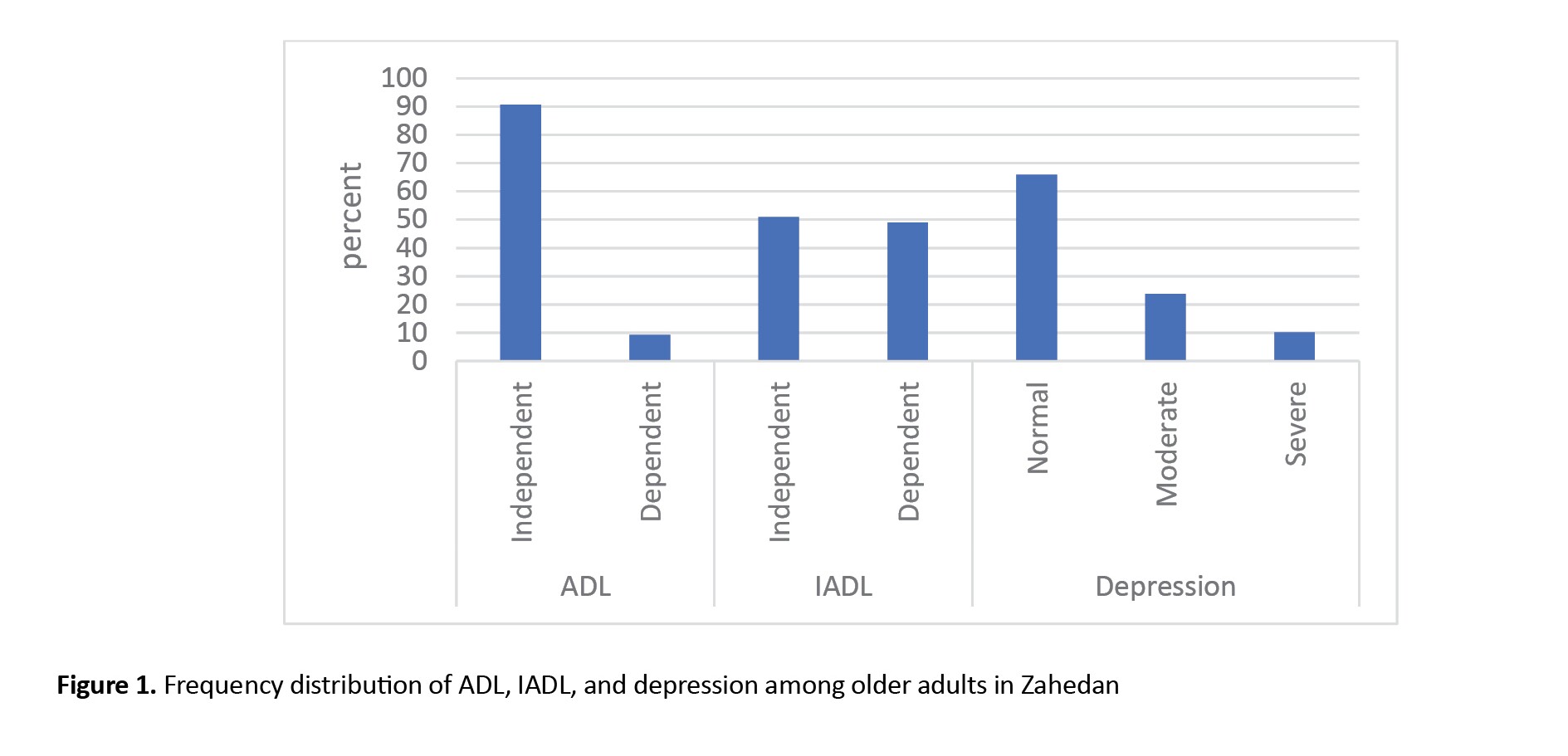

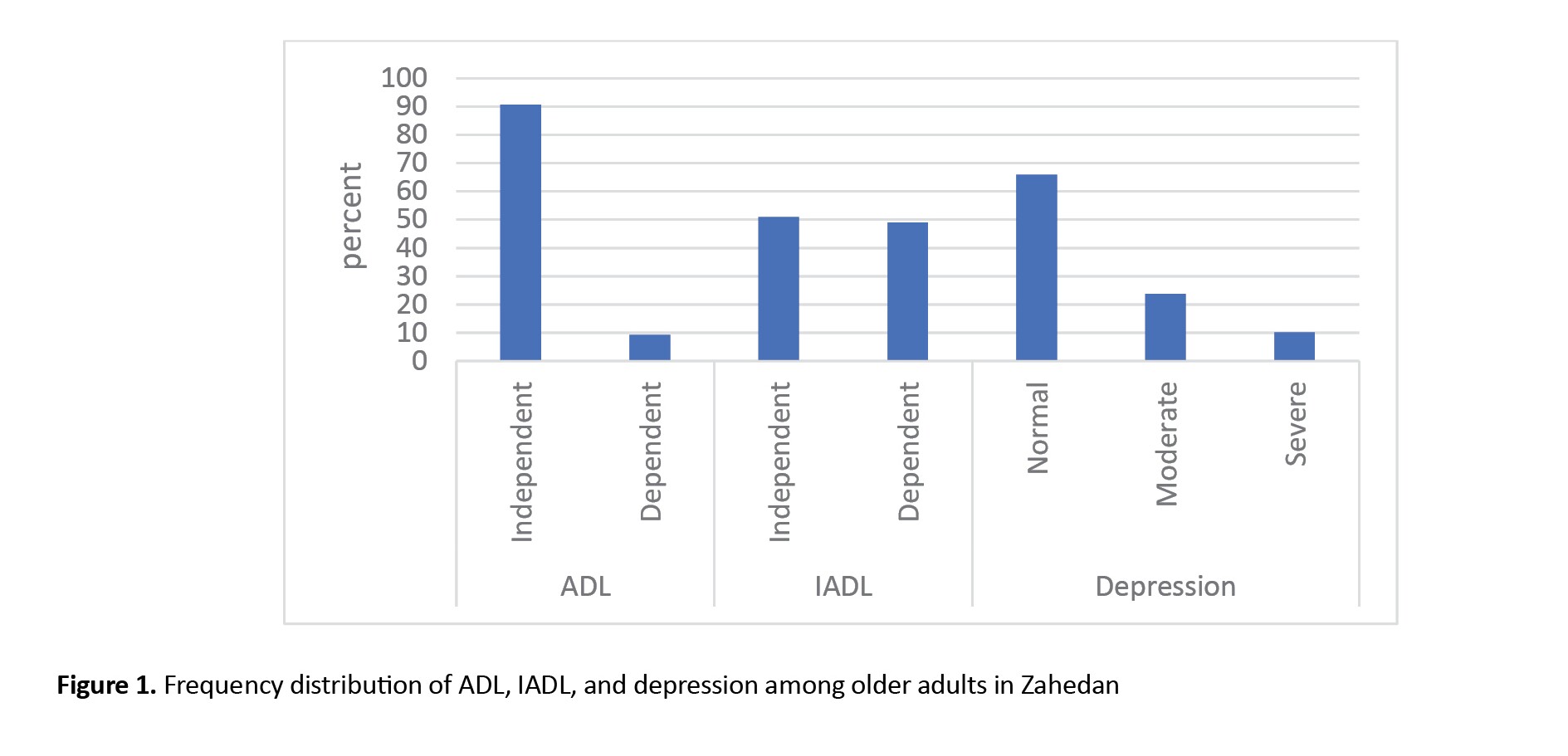

The present study showed that, in general, 30 participants (9.3%) of the older adults surveyed were dependent in terms of ADL, and 159 participants (49.1%) were dependent in terms of IADL, indicating they performed daily life tasks and affairs on their own.

Additionally, 33 participants (10.19%) had severe depression, and 77 participants (23.77%) had moderate depression, while the rest were considered healthy in this regard (Figure 1).

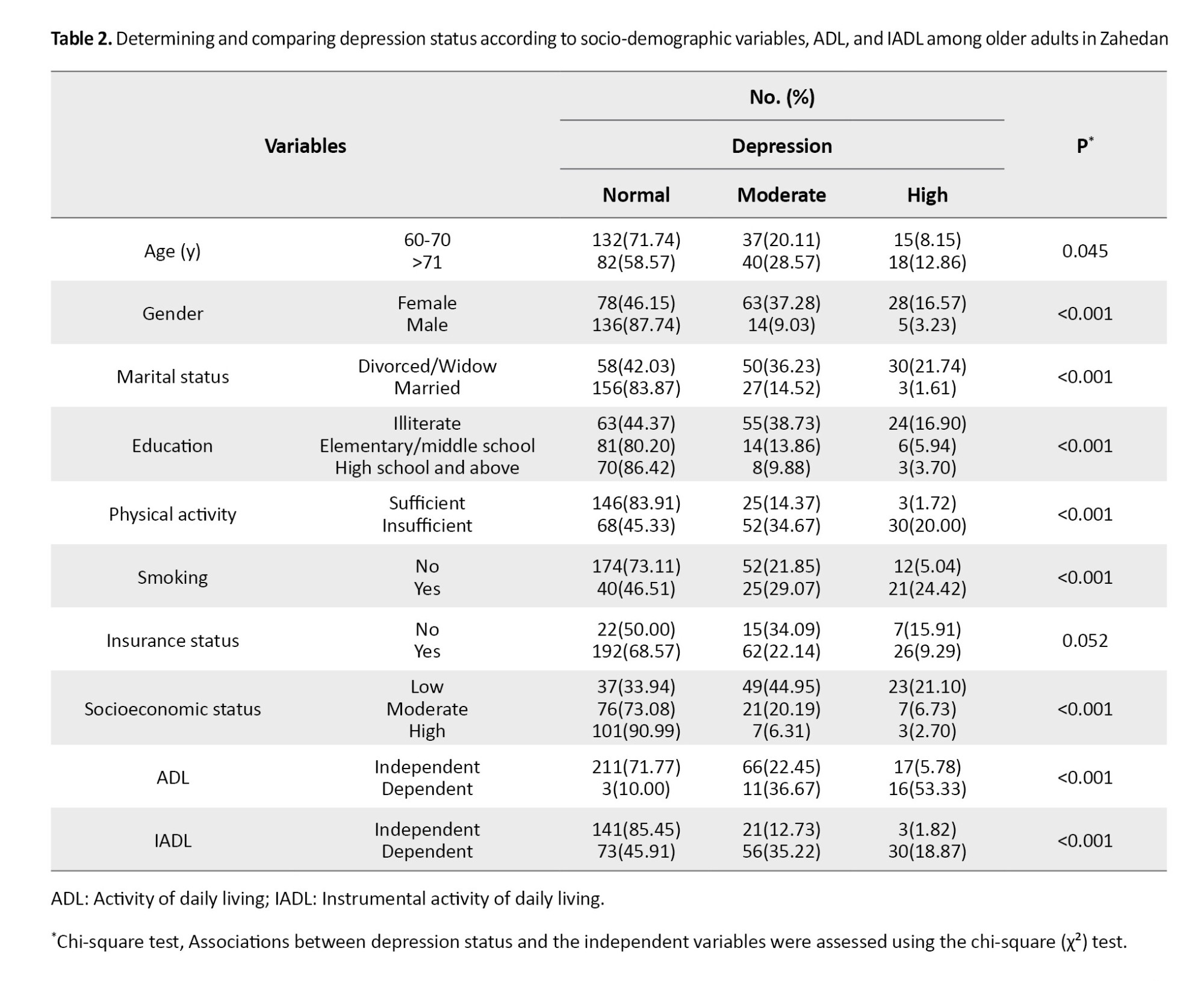

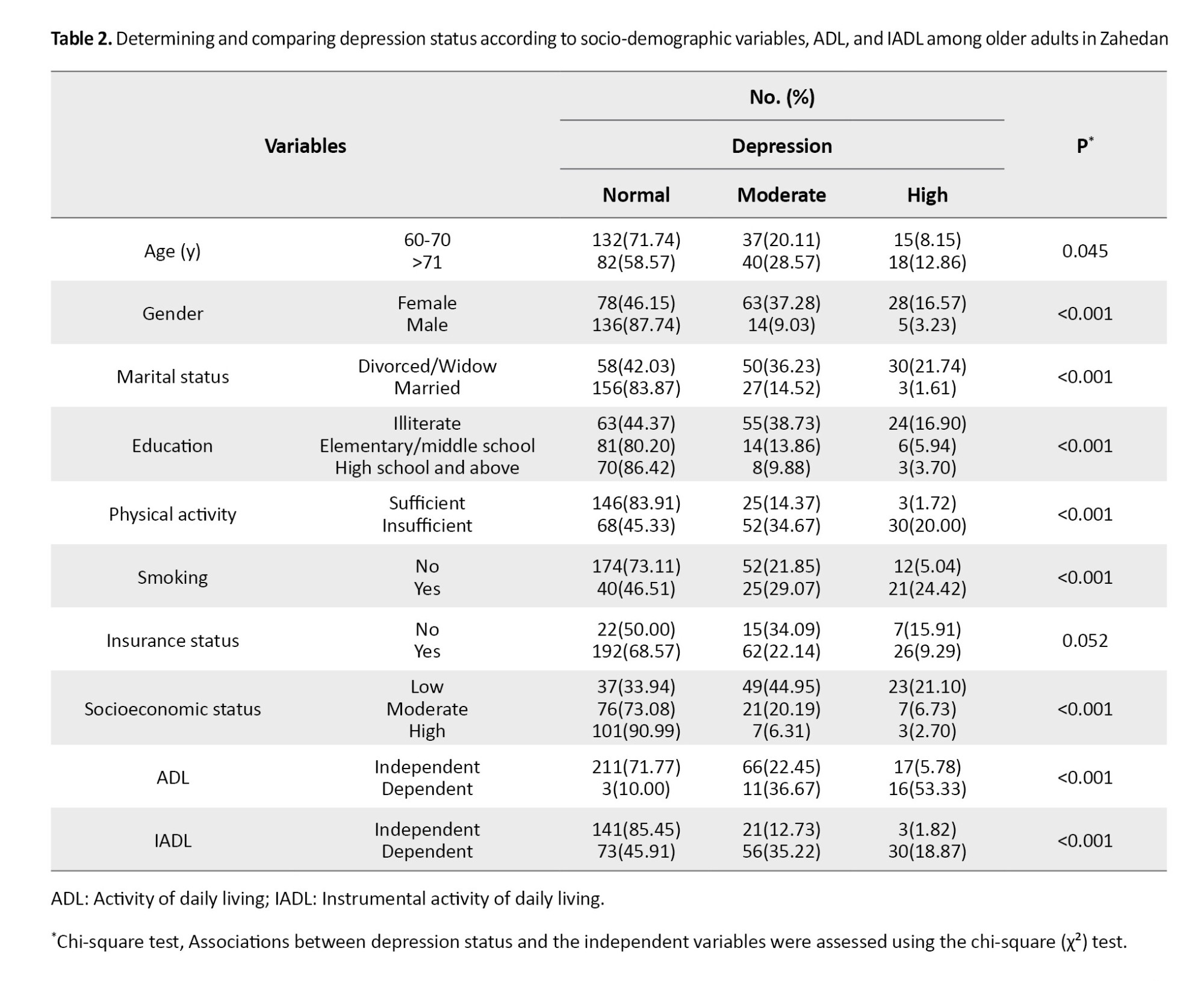

Individuals aged over 71 years exhibited a higher prevalence of severe and moderate depression compared to those aged 60-70 years (P=0.045). Similarly, severe and moderate depression were significantly more common in elderly women, divorced/widowed, those with low education, those with insufficient physical activity, smokers, those without health insurance, those with low socioeconomic status, and those dependent in terms of performing ADL and IADL (P<0.05) (Table 2).

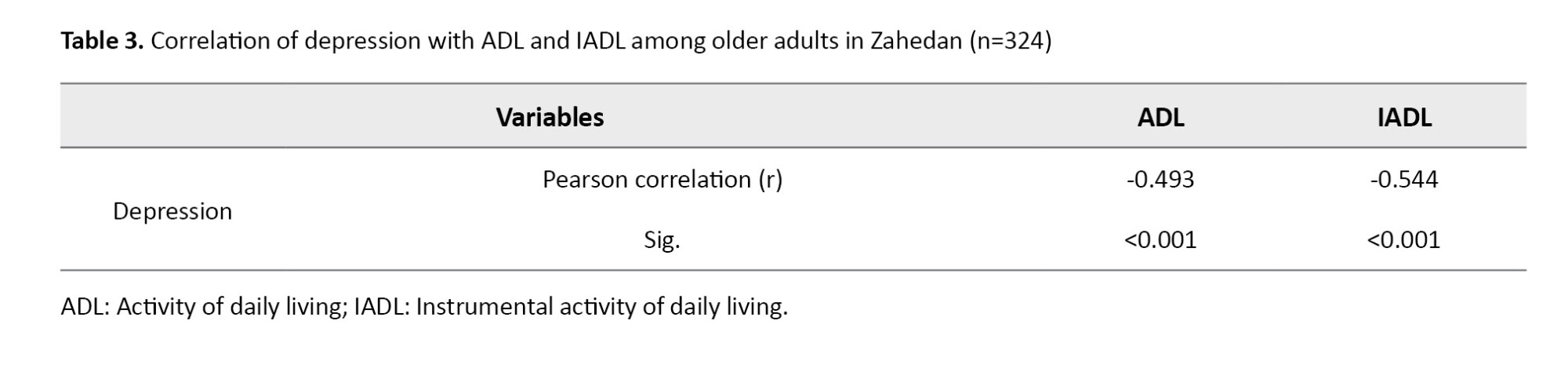

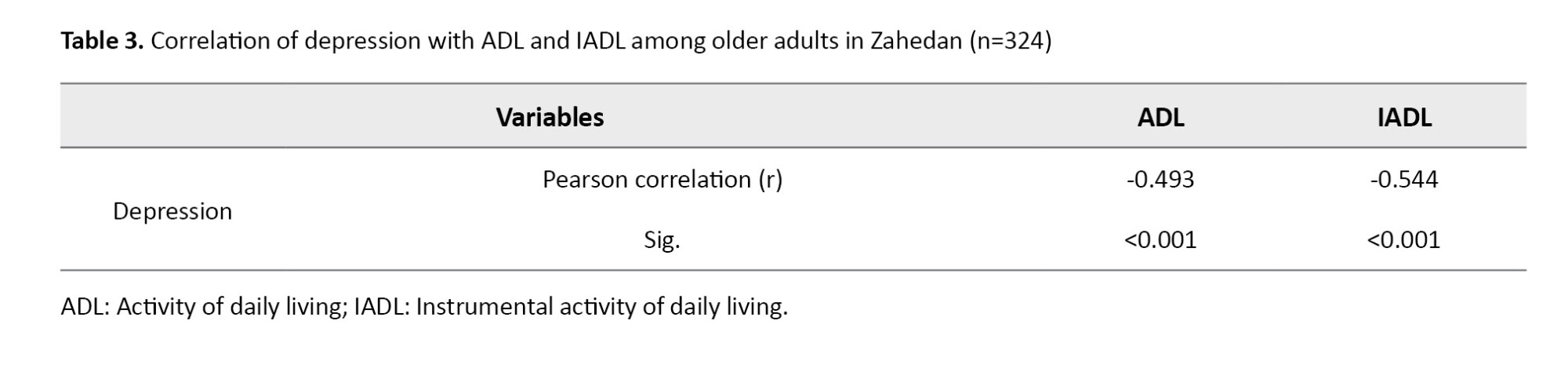

The normality of the data was confirmed using the Shapiro–Wilk test, and to examine the relationship between depression, ADL, and IADL, the Pearson correlation coefficient was used. There was a significant negative relationship between depression and ADL (r=-0.493, P<0.001), and between depression and IADL (r=-0.544, P<0.001) among older adults. This indicates that higher levels of depression are associated with greater limitations in both ADL, IADL. The Pearson correlation coefficients (r) represent the effect sizes for these associations, suggesting a moderate-to-strong relationship in both cases (Table 3).

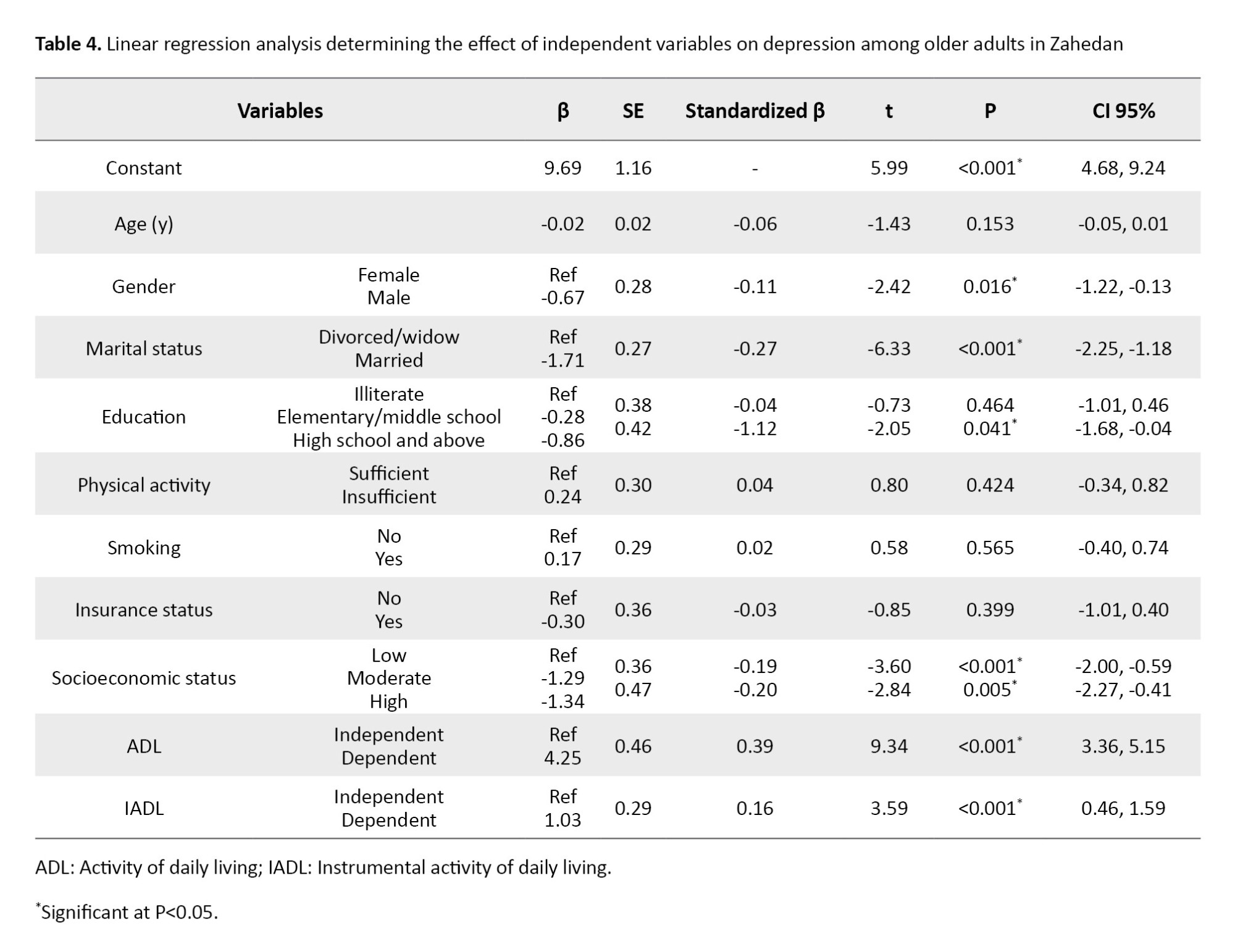

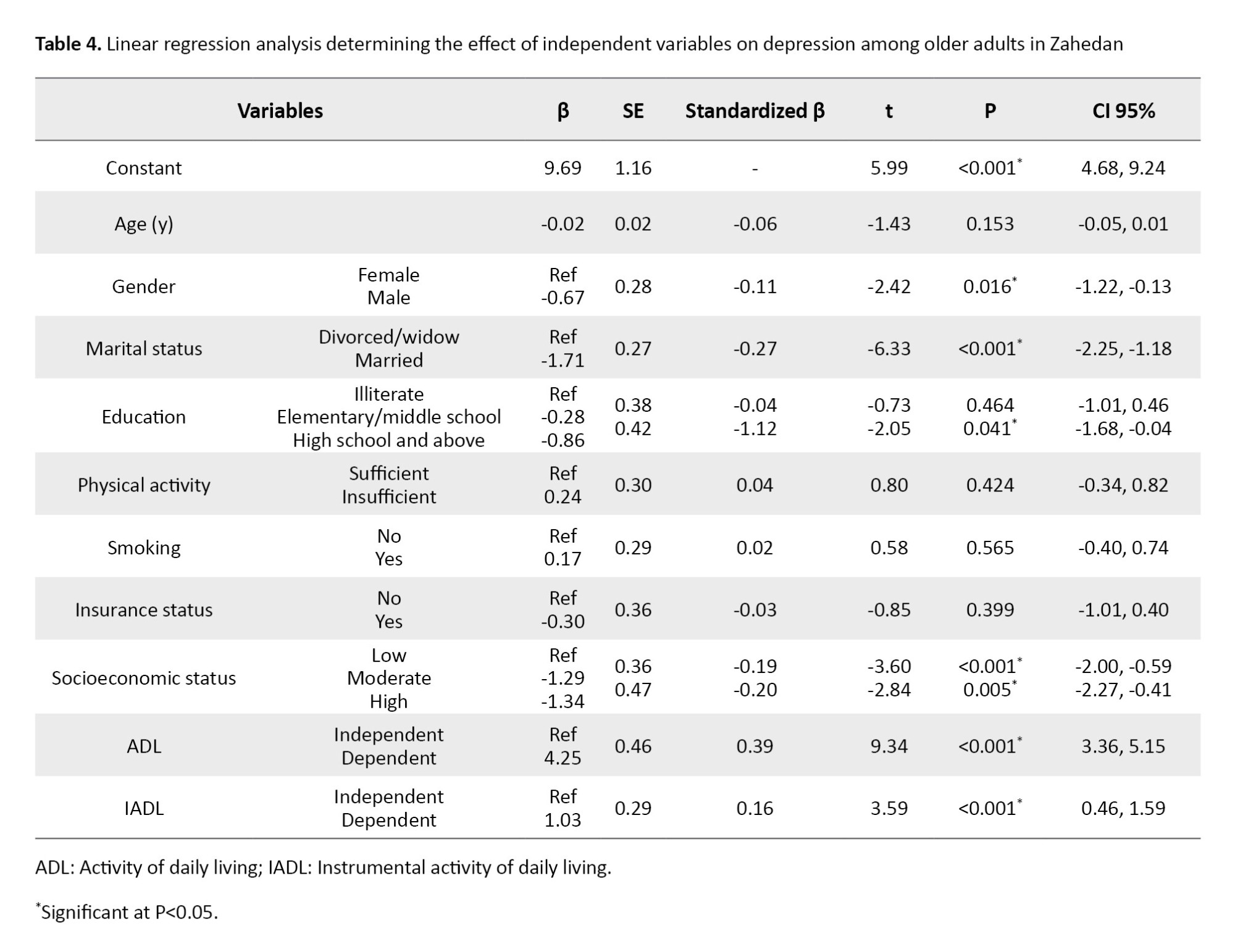

To determine the predictor variables of depression, a linear regression model was utilized, with depression as the response variable and other relevant variables as predictors. Prior to the analysis, all critical assumptions for linear regression were thoroughly assessed: the dependent variable (depression score) exhibited a normal distribution as confirmed by the Shapiro-Wilk test, residuals also followed a normal distribution with a mean of zero and constant variance, their independence was verified, and multicollinearity among independent variables was assessed using variance inflation factor (VIF). The mean VIF was calculated to be 1.81, which is well below typical thresholds, suggesting no significant multicollinearity issues. Upon confirmation of these assumptions, the overall regression model was found to be statistically significant (F=38.17, P<0.001). However, gender, marital status, education, socioeconomic status, ADL, and IADL remained in the model as predictors of individual depression. This study showed that, with other variables held constant, the depression score in men was on average 0.67 points lower than that of women (β=-0.67, t=-2.42, P=0.016), and the depression score in married people was on average 1.71 points lower than that of widows/divorced older adults (β= -1.71, t=-6.33, P<0.001). The depression score in participants with a high level of education was, on average, 0.86 points lower than that of illiterate older adults (β= -0.86, t=-2.05, P=0.041). Similarly, the depression scores in participants with high and moderate socioeconomic status were, on average, 1.34 points and 1.29 points lower than those of participants with low socioeconomic status, respectively.

Also, under constant conditions, the depression scores in participants who were dependent on ADL and IADL were on average 4.25 and 1.03 points higher than the depression scores in people who were independent on ADL and IADL. The goodness of fit for this model (adjusted R-square) was 0.58, indicating that 58% of the observed dispersion in this model was explained by these variables, and the variables of gender, high education, socioeconomic status, ADL, and IADL were significant (Table 4).

Discussion

This study aimed to determine the relationship between depression and IADL and IADL among older adults in Zahedan in 2024. The study included a sample of 324 older adults from Zahedan. Our study found the prevalence of severe and moderate depression to be 10.2% and 23.8% respectively, resulting in an overall depression rate of 34.0%. These findings align with previous research by Kang et al. and Feng et al. [22, 23]. Additionally, our observed rate of severe depression (9.5%) is largely consistent with the results reported by Mohamadzadeh et al. [24]. However, a notable contrast emerges when comparing our findings with those of other studies that report significantly higher prevalence rates of depression. For example, studies by karami et al. Mostfa et al. and Xue et al. which were conducted on 8,526 elderly individuals in Shanxi Province, reported general depression prevalences as high as 67.6%, 82%, and 62.1%, respectively [25-27]. From a methodological standpoint, these discrepancies can arise from several key areas. Firstly, variations in the specific diagnostic instruments or questionnaires employed across studies can significantly impact reported prevalence rates, as different tools may vary in their sensitivity, specificity, and the particular constructs of depression they capture. Secondly, differences in sample characteristics, including sample size and demographic profiles (e.g. age range, socioeconomic status), can also play a crucial role in shaping study outcomes. Furthermore, cultural and socio-ethnic factors exert a profound influence on the manifestation and reporting of depression. Cultural norms and the pervasive stigma often associated with mental health issues can lead to considerable underreporting of symptoms in certain contexts, whereas in others, expressions of psychological distress might be more readily recognized as depressive symptoms [28]. This divergence likely stems from variations in social, cultural, and economic factors.

Our study showed that 9.3% of the older adults were dependent in terms of performing ADL. Studies by Patel et al. in 2021 and Mobasseri et al. in 2024 are almost in line with our study [29, 30]. Our study also showed that 49.1% of participants are dependent in terms of performing IADL, which aligns with the studies of Chauhan et al. in India and Hosseini et al. in Iran [13, 31]. However, in relation to these findings, the results were contradictory. For example, in the study by Villarreal et al. in 2018, the prevalence of disability in ADL and IADL was 53.5% and 66.8%, respectively [32], and in the study by Burman et al. these values were also not consistent with our findings [33]. It has been suggested that differences in definitions of disability, variations in care and health systems at different levels, cultural differences, and diverse methodologies in studies are reasons for these contradictory results [11, 33].

There was a negative and inverse relationship between ADL and IADL and depression, which is consistent with several studies [22-24]. However, it was not consistent with the study by Nakamura et al. in 2017 [34]. The observed relationship between the inability to perform ADL/IADL and increased depression in older adults can be understood through several potential mechanisms. Firstly, the loss of independence and self-efficacy stemming from dependency can significantly impact mental well-being [26]. Secondly, the diminished capacity to engage in daily activities often leads to reduced social interaction and potential isolation, which are well-established risk factors for depression [35].

The results of our regression model showed that depression scores were higher in women. This finding is consistent with the results of Xue et al. and Yang et al. [27, 36]. Women are more susceptible to depression than men due to financial dependence and psychological stress caused by childbirth and postpartum care, being more emotional, and having a longer life expectancy [36-38]. Also, recent research indicates that biological factors, such as fluctuations in ovarian hormone levels and specifically reduced estrogen, may play a role in the heightened incidence of depression and anxiety among women [39].

The findings showed that depression was less common in married people, which is consistent with many studies [36, 40]. Although the study by Nakamura et al. of the elderly in Kurabuchi Town did not find an association between marriage and depression [34], people without a spouse are more likely to develop depression due to less emotional support, feelings of loneliness, and lack of companionship [36].

The results indicated that higher education and higher socioeconomic status were effective in reducing depression, which aligns with the findings of Xue et al. and Srivastava et al. [27, 40]. Studies have shown that these two factors have a great impact on people’s lifestyles. Also, older adults with poor economic and social status are more prone to risky behaviors and endanger their health, and this decrease in people’s health is a reason for mental disorders, including depression. Furthermore, individuals with lower education levels are more likely to have lower incomes and, due to their low social status, participate less in social activities, thereby increasing their chances of depression [27, 36].

On the other hand, as emphasized in the study by Papi et al. educational attainment acts as a robust protective factor against cognitive decline and enhances cognitive functional capacity. Considering this finding and the established reciprocal relationship between cognitive impairment and depression, increasing levels of education can serve as an effective preventative strategy, directly impacting the reduction in the prevalence of depression in older age [35, 41].

Conclusion

The ability of the elderly to perform ADL and IADL, gender, marital status, education, and socioeconomic status are good predictors of depression in older adults. Therefore, attention to improving daily activities, promoting education, and providing financial and social support is essential. Facilitating the creation of flexible part-time job opportunities tailored to the abilities of seniors through local job placements, activating retirement centers for social programs and volunteer activities, and providing free or subsidized specialized assistive devices (e.g. walkers, bathroom equipment) can help reduce depression in this group.Establishing social groups for the elderly, educational programs to increase the level of education and skills of the elderly, and group activities, such as art classes, workshops, or discussion sessions can be beneficial in increasing social connections and reducing feelings of loneliness. These programs can also help increase self-confidence and improve their socio-economic status. Therefore, by creating a supportive environment and providing appropriate opportunities, the quality of life of the elderly can be improved, increasing their sense of satisfaction and happiness, and reducing depression. While this study identifies significant associations, it is recommended that future longitudinal research be conducted to definitively establish causal relationships between the aforementioned factors and depression in older adults.

Study limitations

This study had some limitations, including the cross-sectional design of the study, which made it difficult to interpret causal results. Also, data were collected through a questionnaire, which may have made participants reluctant to respond due to the large number of questions. However, the researcher made every effort to convince the elderly and motivate them to answer the questions. Additionally, as an observational study, there is an inherent risk of residual confounding, which occurs when unmeasured or inadequately controlled factors could affect the observed relationships.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Zahedan University of Medical Sciences, Zahedan, Iran (Code: IR.ZAUMS.REC.1403.150). Informed consent was obtained from all participants before their inclusion in the study.

Funding

This article was extracted from the master thesis of Shima Khosravi, approved by Zahedan University of Medical Sciences, Zahedan, Iran.

Authors contributions

All authors participated in the design, implementation, and writing of all parts of the present study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to the respected elderly individuals and to all those who provided the necessary cooperation in carrying out this research project.

References

Aging is a natural, inevitable, gradual, and progressive process that encompasses the lives of all humans. At this stage of life, cell proliferation decreases and eventually stops [1]. Estimates show that the global population aged 65 and over will increase by 6% from 2022 to 2050, while the population aged 80 and over will increase by 283 million from 2019 to 2025 [2]. Iran is also facing an aging phenomenon due to demographic transition and declining birth rates, such that by 2050, the population aged 60 and over will reach 31% [3].

Given this growing trend, it is important to pay attention to the major problems of aging, including mental disorders, such as anxiety, depression, and stress [4]. Factors, such as chronic illnesses, the death of friends and acquaintances, physical weakness, decreased vision and hearing, inability to perform daily activities, and financial problems due to inability to work can cause or exacerbate emotions, such as stress, anxiety, sadness, hopelessness, and depression [5]. The prevalence of depression fluctuates across different regions due to a combination of factors, including varying risk factors, divergent study methodologies, dissimilar data collection instruments, and distinct geographical and population characteristics [6]. In a meta-analysis conducted in 2024, its rates in Africa, Europe, Australia and Asia was reported to be 26.3%, 12.3%, 27.8% and 28.3%, respectively [7]. According to a study by Jafari et al. in 2021, 52% of older adults experienced depression [8].

Physical functioning is a factor that can affect the mental health of older adults [9]. This index is used to assess the level of quality and health of life among older adults, which is measured and evaluated by concepts, such as activities of daily living (ADL) that refers to routine daily activities, such as eating, transportation, self-care, using the toilet, bathing, walking, climbing stairs, dressing and undressing, and controlling urination and defecation [10], and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), which include using the telephone, shopping, cooking, taking care of housework, doing laundry, taking medication, and controlling income and expenses. The conceptual framework distinguishes IADLs from ADLs by their engagement with more complex activities [11]. The inability to perform these activities can have detrimental effects, such as reduced quality of life and social participation, and is a risk factor for anxiety and depression [9]. Therefore, given the negative and significant correlation between performing these activities and multiple mental disorders [12], and given the importance of the health status of the elderly, there is a pressing need to understand these relationships in specific sociocultural contexts.

While previous studies have addressed different aspects of elderly well-being, there is a significant research gap in comprehensively examining depression and its multifaceted relationship with ADL and IADL, particularly among the elderly in Zahedan. Existing research may be limited due to its geographical scope, focus on only one type of activity (ADL or IADL), or failure to fully consider the unique demographic and socioeconomic factors prevalent in this particular region. Therefore, this study aimed to determine the relationship between depression and ADL and IADL among older adults in Zahedan in 2024. The innovation of this research lies in its comprehensive approach to examining these associated factors in a previously understudied population, thereby providing essential data for targeted health interventions and policies in the region. Specifically, this study sought to answer the following research questions: 1) What is the prevalence of depression among older adults in Zahedan? 2) Is there a significant relationship between depression and ADL among older adults in Zahedan? 3) Is there a significant relationship between depression and IADL among older adults in Zahedan? 4) Is there a significant relationship between depression and socio-demographic among older adults in Zahedan?

Materials and Methods

Type of study

The present study is cross-sectional and was conducted using a descriptive-analytical method.

Participants

The study population consisted of 324 older adults (aged 60 years and above) who were attendees at health centers located in Zahedan city.

Sampling method and sample size

Based on a reported prevalence of 22% for dependence in ADL in the study by Chauhan et al. [13], and considering a significance level of 0.05 and a maximum allowable error of 0.05, the minimum required sample size was calculated to be approximately 270 participants using the prevalence estimation formula [14]. Furthermore, accounting for the multi-stage cluster sampling method and incorporating a design effect of 1.2 to adjust for potential intra-cluster correlation, the final determined sample size was increased to 324 individuals.

The sampling method employed was multi-stage cluster sampling. Initially, the health and treatment centers in Zahedan city were considered as clusters (57 clusters). Subsequently, 8 clusters were selected using a simple random sampling method. These selected clusters demonstrated a relatively uniform distribution across different postal areas of the city. According to statistics from the Deputy of Health, there was no significant difference in the population covered by each cluster, and given the high intra-cluster correlation coefficient, it is believed that the sample selection from the clusters was without bias. Consequently, approximately 40 samples were selected from each cluster. On one or more consecutive days, visitors to the health and treatment centers were requested to introduce elderly individuals from their households who met the study’s inclusion criteria. Following their agreement and consent, the researcher visited the elderly individuals’ homes to complete the questionnaires. It is noteworthy that to ensure randomness in sample selection, the researcher randomly chose one day of the week to visit each health and treatment center. The data collection method involved face-to-face interviews, and the data collection tool was a written questionnaire. Data were collected via face-to-face interviews conducted by a trained interviewer with a master’s degree in epidemiology.

Instrument

The used questionnaire consisted of 4 parts. The first part, the socio-demographic questionnaire, included questions about age, gender, marital status, education level, physical activity, smoking, insurance coverage, and socioeconomic status. It should be noted that sufficient physical activity was defined as engaging in aerobic activity, such as walking for at least 30 minutes on 5 days a week. Smoking was also considered as follows: If the person did not smoke, he/she was classified in the never group; if the person smoked at least once a month, he/she was classified in the sometimes group; if the person smoked at least once a week, he/she was classified in the often group; and if the person smoked every day, he/she was classified in the always group. However, due to the small number of samples in the sometimes, often, and always groups, these groups were merged. Socioeconomic status was determined using variables, such as literacy level, occupation, and household assets (such as car, television, refrigerator, etc.) using the principal component analysis categorical principal component analysis (CAT PCA) method. Given that there is a correlation between these variables, to avoid collinearity in the model using the variables mentioned in the questionnaire, the subjects were classified into one of the levels of low, moderate, and high socioeconomic status based on the 33rd and 66th percentiles.

The second part, the ADL Questionnaire with the modified Barthel scale (10-item version) [15], was completed to assess the level of ability and independence in performing ADL for the desired samples. This tool includes 10 questions, including “eating”, “moving and commuting”, “going up and down stairs”, “changing clothes”, “bathing”, “defecating”, “moving and getting out of bed”, “personal hygiene”, “going to the bathroom” and “urinating”. The total score is 0-100. Dependency levels were categorized as follows: Scores of 0 to 66 indicated dependence, while scores of 67 to 100 indicated independence.

The third part, the IADL Questionnaire, is based on the Lawton and Brody [16] criteria. This questionnaire has 7 items: “Using the telephone”, “taking medication”, “preparing food”, “doing housework”, “shopping for necessities”, “using vehicles”, and “controlling income and expenditure”. The total score ranges from 0 to 14. Scores of 0 to 10 are classified as dependent and 11 to 14 as independent. In 2016, Taheri Tanjani et al. [17] found the sensitivity and specificity for ADL to be 0.75 and 0.96, respectively, and for IADL to be 0.71 and 0.77. They also reported that Cronbach’s α and intraclass correlation for both questionnaires were >0.75. Also, in the study by Mehraban et al. [18], it was found that the Lawton Scale has very good reliability and validity.

The fourth part, depression, was measured using the geriatric depression scale–15 (GDS-15). Yesavage and Sheikh [19] extracted this scale in 1986 from the 30-question version of the depression questionnaire. This questionnaire has 15 yes or no questions, and the classification of individuals is as follows: If an individual receives a score of less than 5, he/she is normal, a score of 5-9 indicates moderate depression, and a score of 10-15 indicates severe depression. In Iran, Malakouti et al. [20] reported their alpha coefficient and reliability as 0.96 and 0.85, respectively. Also, in the study by Soltaninejad et al. [21] in 2025, the GDS-15 was used to measure depression. The Persian version of this questionnaire had very high reliability, with Cronbach’s α of 0.94 and ICC of 0.92.

To confirm the reliability of the questionnaires, a pilot study was conducted with 30 older adults. The cronbach’s α coefficients for the ADL questionnaire, IADLquestionnaire, and GDS-15 were 0.90, 0.83, and 0.87, respectively.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria included individuals aged 60 years and older, willingness of the elderly to cooperate in the study, ability to communicate verbally, non-dependence of the elderly on bed rest, and absence of Alzheimer’s disease. The exclusion criteria included failure to complete some parts of the questionnaire. Depression status was not an inclusion or exclusion criterion; rather, depression levels were measured as a primary variable of interest in all participants.

Data analysis method

In the analyses of this study, STATA software, version 17 was utilized. To examine the normality of quantitative data, the Shapiro–Wilk test was used, and the data were presented as Mean±SD or frequency (percentage). The chi-square test, Pearson correlation coefficient, and regression analysis were used to examine the relationship and correlation between variables. The significance level for all statistical analyses was set at P<0.05.

Ethical consideration

Prior to data collection, all participants provided written informed consent, thereby ensuring their voluntary involvement and comprehensive understanding of the study’s nature and procedures. Participants were explicitly informed of their right to refuse participation or withdraw at any point without penalty, and their decisions were fully respected. Confidentiality was strictly maintained for all collected data. No compensation was provided to avoid any undue influence on participation, thus upholding the impartiality and accuracy of the data. The informed consent process also ensured participants understood their rights regarding personal data processing and their ability to object or withdraw consent at any stage, reinforcing their control over their information and privacy.

Results

The mean age of the participants in this study was 70.84±18.8 with an age range of 60 to 99 years. In terms of age frequency distribution, 184 participants (56.8%) were between 60 and 70 years, and 140(43.2%) were 71 years and older. Also, 169 participants (52.2%) were female. In terms of marital status, 186 cases (57.4%) were married, and the rest of the older adults were widowed or divorced. In terms of education level, 142 cases (43.8%) were illiterate, 101(31.2%) had completed elementary and middle school, while the others were in high school or above. Regarding physical activity, 174 subjects (53.7%) were physically active. Also, in terms of smoking, 238 subjects (73.5%) did not smoke, and regarding insurance coverage, 280 subjects (86.4%) had insurance. Furthermore, 111 participants (34.3%) belonged to the high socioeconomic status category (Table 1).

The present study showed that, in general, 30 participants (9.3%) of the older adults surveyed were dependent in terms of ADL, and 159 participants (49.1%) were dependent in terms of IADL, indicating they performed daily life tasks and affairs on their own.

Additionally, 33 participants (10.19%) had severe depression, and 77 participants (23.77%) had moderate depression, while the rest were considered healthy in this regard (Figure 1).

Individuals aged over 71 years exhibited a higher prevalence of severe and moderate depression compared to those aged 60-70 years (P=0.045). Similarly, severe and moderate depression were significantly more common in elderly women, divorced/widowed, those with low education, those with insufficient physical activity, smokers, those without health insurance, those with low socioeconomic status, and those dependent in terms of performing ADL and IADL (P<0.05) (Table 2).

The normality of the data was confirmed using the Shapiro–Wilk test, and to examine the relationship between depression, ADL, and IADL, the Pearson correlation coefficient was used. There was a significant negative relationship between depression and ADL (r=-0.493, P<0.001), and between depression and IADL (r=-0.544, P<0.001) among older adults. This indicates that higher levels of depression are associated with greater limitations in both ADL, IADL. The Pearson correlation coefficients (r) represent the effect sizes for these associations, suggesting a moderate-to-strong relationship in both cases (Table 3).

To determine the predictor variables of depression, a linear regression model was utilized, with depression as the response variable and other relevant variables as predictors. Prior to the analysis, all critical assumptions for linear regression were thoroughly assessed: the dependent variable (depression score) exhibited a normal distribution as confirmed by the Shapiro-Wilk test, residuals also followed a normal distribution with a mean of zero and constant variance, their independence was verified, and multicollinearity among independent variables was assessed using variance inflation factor (VIF). The mean VIF was calculated to be 1.81, which is well below typical thresholds, suggesting no significant multicollinearity issues. Upon confirmation of these assumptions, the overall regression model was found to be statistically significant (F=38.17, P<0.001). However, gender, marital status, education, socioeconomic status, ADL, and IADL remained in the model as predictors of individual depression. This study showed that, with other variables held constant, the depression score in men was on average 0.67 points lower than that of women (β=-0.67, t=-2.42, P=0.016), and the depression score in married people was on average 1.71 points lower than that of widows/divorced older adults (β= -1.71, t=-6.33, P<0.001). The depression score in participants with a high level of education was, on average, 0.86 points lower than that of illiterate older adults (β= -0.86, t=-2.05, P=0.041). Similarly, the depression scores in participants with high and moderate socioeconomic status were, on average, 1.34 points and 1.29 points lower than those of participants with low socioeconomic status, respectively.

Also, under constant conditions, the depression scores in participants who were dependent on ADL and IADL were on average 4.25 and 1.03 points higher than the depression scores in people who were independent on ADL and IADL. The goodness of fit for this model (adjusted R-square) was 0.58, indicating that 58% of the observed dispersion in this model was explained by these variables, and the variables of gender, high education, socioeconomic status, ADL, and IADL were significant (Table 4).

Discussion

This study aimed to determine the relationship between depression and IADL and IADL among older adults in Zahedan in 2024. The study included a sample of 324 older adults from Zahedan. Our study found the prevalence of severe and moderate depression to be 10.2% and 23.8% respectively, resulting in an overall depression rate of 34.0%. These findings align with previous research by Kang et al. and Feng et al. [22, 23]. Additionally, our observed rate of severe depression (9.5%) is largely consistent with the results reported by Mohamadzadeh et al. [24]. However, a notable contrast emerges when comparing our findings with those of other studies that report significantly higher prevalence rates of depression. For example, studies by karami et al. Mostfa et al. and Xue et al. which were conducted on 8,526 elderly individuals in Shanxi Province, reported general depression prevalences as high as 67.6%, 82%, and 62.1%, respectively [25-27]. From a methodological standpoint, these discrepancies can arise from several key areas. Firstly, variations in the specific diagnostic instruments or questionnaires employed across studies can significantly impact reported prevalence rates, as different tools may vary in their sensitivity, specificity, and the particular constructs of depression they capture. Secondly, differences in sample characteristics, including sample size and demographic profiles (e.g. age range, socioeconomic status), can also play a crucial role in shaping study outcomes. Furthermore, cultural and socio-ethnic factors exert a profound influence on the manifestation and reporting of depression. Cultural norms and the pervasive stigma often associated with mental health issues can lead to considerable underreporting of symptoms in certain contexts, whereas in others, expressions of psychological distress might be more readily recognized as depressive symptoms [28]. This divergence likely stems from variations in social, cultural, and economic factors.

Our study showed that 9.3% of the older adults were dependent in terms of performing ADL. Studies by Patel et al. in 2021 and Mobasseri et al. in 2024 are almost in line with our study [29, 30]. Our study also showed that 49.1% of participants are dependent in terms of performing IADL, which aligns with the studies of Chauhan et al. in India and Hosseini et al. in Iran [13, 31]. However, in relation to these findings, the results were contradictory. For example, in the study by Villarreal et al. in 2018, the prevalence of disability in ADL and IADL was 53.5% and 66.8%, respectively [32], and in the study by Burman et al. these values were also not consistent with our findings [33]. It has been suggested that differences in definitions of disability, variations in care and health systems at different levels, cultural differences, and diverse methodologies in studies are reasons for these contradictory results [11, 33].

There was a negative and inverse relationship between ADL and IADL and depression, which is consistent with several studies [22-24]. However, it was not consistent with the study by Nakamura et al. in 2017 [34]. The observed relationship between the inability to perform ADL/IADL and increased depression in older adults can be understood through several potential mechanisms. Firstly, the loss of independence and self-efficacy stemming from dependency can significantly impact mental well-being [26]. Secondly, the diminished capacity to engage in daily activities often leads to reduced social interaction and potential isolation, which are well-established risk factors for depression [35].

The results of our regression model showed that depression scores were higher in women. This finding is consistent with the results of Xue et al. and Yang et al. [27, 36]. Women are more susceptible to depression than men due to financial dependence and psychological stress caused by childbirth and postpartum care, being more emotional, and having a longer life expectancy [36-38]. Also, recent research indicates that biological factors, such as fluctuations in ovarian hormone levels and specifically reduced estrogen, may play a role in the heightened incidence of depression and anxiety among women [39].

The findings showed that depression was less common in married people, which is consistent with many studies [36, 40]. Although the study by Nakamura et al. of the elderly in Kurabuchi Town did not find an association between marriage and depression [34], people without a spouse are more likely to develop depression due to less emotional support, feelings of loneliness, and lack of companionship [36].

The results indicated that higher education and higher socioeconomic status were effective in reducing depression, which aligns with the findings of Xue et al. and Srivastava et al. [27, 40]. Studies have shown that these two factors have a great impact on people’s lifestyles. Also, older adults with poor economic and social status are more prone to risky behaviors and endanger their health, and this decrease in people’s health is a reason for mental disorders, including depression. Furthermore, individuals with lower education levels are more likely to have lower incomes and, due to their low social status, participate less in social activities, thereby increasing their chances of depression [27, 36].

On the other hand, as emphasized in the study by Papi et al. educational attainment acts as a robust protective factor against cognitive decline and enhances cognitive functional capacity. Considering this finding and the established reciprocal relationship between cognitive impairment and depression, increasing levels of education can serve as an effective preventative strategy, directly impacting the reduction in the prevalence of depression in older age [35, 41].

Conclusion

The ability of the elderly to perform ADL and IADL, gender, marital status, education, and socioeconomic status are good predictors of depression in older adults. Therefore, attention to improving daily activities, promoting education, and providing financial and social support is essential. Facilitating the creation of flexible part-time job opportunities tailored to the abilities of seniors through local job placements, activating retirement centers for social programs and volunteer activities, and providing free or subsidized specialized assistive devices (e.g. walkers, bathroom equipment) can help reduce depression in this group.Establishing social groups for the elderly, educational programs to increase the level of education and skills of the elderly, and group activities, such as art classes, workshops, or discussion sessions can be beneficial in increasing social connections and reducing feelings of loneliness. These programs can also help increase self-confidence and improve their socio-economic status. Therefore, by creating a supportive environment and providing appropriate opportunities, the quality of life of the elderly can be improved, increasing their sense of satisfaction and happiness, and reducing depression. While this study identifies significant associations, it is recommended that future longitudinal research be conducted to definitively establish causal relationships between the aforementioned factors and depression in older adults.

Study limitations

This study had some limitations, including the cross-sectional design of the study, which made it difficult to interpret causal results. Also, data were collected through a questionnaire, which may have made participants reluctant to respond due to the large number of questions. However, the researcher made every effort to convince the elderly and motivate them to answer the questions. Additionally, as an observational study, there is an inherent risk of residual confounding, which occurs when unmeasured or inadequately controlled factors could affect the observed relationships.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Zahedan University of Medical Sciences, Zahedan, Iran (Code: IR.ZAUMS.REC.1403.150). Informed consent was obtained from all participants before their inclusion in the study.

Funding

This article was extracted from the master thesis of Shima Khosravi, approved by Zahedan University of Medical Sciences, Zahedan, Iran.

Authors contributions

All authors participated in the design, implementation, and writing of all parts of the present study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to the respected elderly individuals and to all those who provided the necessary cooperation in carrying out this research project.

References

- Flint B, Tadi P. Physiology, aging. StatPearls. Treasure Island: StatPearls Publishing; 2025. [Link]

- Marbaniang SP, Chungkham HS. Latent class of multidimensional dependency in community-dwelling older adults: Evidence from the longitudinal ageing study in India. BMC Geriatrics. 2024; 24(1):203. [DOI:10.1186/s12877-024-04813-9] [PMID]

- Mehri N, Messkoub M, Kunkel S. Trends, Determinants and the Implications of Population Aging in Iran. Ageing International. 2020;45(4):327-43. [DOI:10.1007/s12126-020-09364-z]

- Piadehkouhsar M, Ahmadi F, Khoshknab MF, Rasekhi AA. The effect of orientation program based on activities of daily living on depression, anxiety, and stress in the elderly. International Journal of Community Based Nursing and Midwifery. 2019; 7(3):170. [DOI:10.30476/IJCBNM.2019.44992] [PMID]

- Mohamadabad M, Hoseinzade Y. [The role of health locus of control in predicting depression symptoms in a sample of iranian older adults with chronic diseases (Persian)]. Journal of Geriatric Nursing. 2016; 2(4):35-48. [DOI:10.21859/jgn.2.4.35]

- Abdoli N, Salari N, Darvishi N, Jafarpour S, Solaymani M, Mohammadi M, et al. The global prevalence of major depressive disorder (MDD) among the elderly: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2022; 132:1067-73. [DOI:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.10.041] [PMID]

- Jalali A, Ziapour A, Karimi Z, Rezaei M, Emami B, Kalhori RP, et al. Global prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress in the elderly population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatrics. 2024; 24(1):809. [DOI:10.1186/s12877-024-05311-8] [PMID]

- Jafari H, Ghasemi-Semeskandeh D, Goudarzian AH, Heidari T, Jafari-Koulaee A. Depression in the Iranian elderly: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Aging Research. 2021; 2021(1):9305624. [DOI:10.1155/2021/9305624] [PMID]

- Zheng J, Xu J, Liu D. The effect of activities of daily living on anxiety in older adult people: The mediating role of social participation. Frontiers in Public Health. 2024; 12:1450826. [DOI:10.3389/fpubh.2024.1450826] [PMID]

- Storeng SH, Sund ER, Krokstad S. Factors associated with basic and instrumental activities of daily living in elderly participants of a population-based survey: The Nord-trøndelag health study, norway. BMJ Open. 2018; 8(3):e018942. [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018942] [PMID]

- Beltz S, Gloystein S, Litschko T, Laag S, van den Berg N. Multivariate analysis of independent determinants of ADL/IADL and quality of life in the elderly. BMC Geriatrics. 2022; 22(1):894. [DOI:10.1186/s12877-022-03621-3] [PMID]

- Mirshekar S, Ahmadi V, Valizadeh H. [The relationship between activities of daily living and psychological distress in older adults: The mediating role of loneliness (Persian)]. Aging Psychology. 2023; 9(3):241-23. [DOI:10.22126/jap.2023.9166.1708]

- Chauhan S, Kumar S, Bharti R, Patel R. Prevalence and determinants of activity of daily living and instrumental activity of daily living among elderly in India. BMC Geriatrics. 2022; 22(1):64. [DOI:10.1186/s12877-021-02659-z] [PMID]

- Chow SC, Shao J, Wang H, Lokhnygina Y. Sample size calculations in clinical research. New York: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2017. [DOI:10.1201/9781315183084]

- Shah S, Vanclay F, Cooper B. Improving the sensitivity of the barthel index for stroke rehabilitation. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1989; 42(8):703-9. [DOI:10.1016/0895-4356(89)90065-6] [PMID]

- Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969; 9(3):179-86. [DOI:10.1093/geront/9.3_Part_1.179] [PMID]

- Taheri Tanjani, Azadbakht M. [Psychometric properties of the persian version of the activities of daily living scale and instrumental activities of daily living scale in elderly (Persian)]. Journal of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences. 2016; 25(132):103-12. [Link]

- Mehraban AH, Soltanmohamadi Y, Akbarfahimi M, Taghizadeh G. Validity and reliability of the persian version of lawton instrumental activities of daily living scale in patients with dementia. Medical Journal of the Islamic Republic of Iran. 2014; 28:25. [PMID]

- Yesavage JA, Sheikh JI. 9/Geriatric depression scale (GDS) recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clinical Gerontologist. 1986; 5(1-2):165-73. [DOI:10.1300/J018v05n01_09]

- Malakouti SK, Fatollahi P, Mirabzadeh A, Salavati M, Zandi T. Reliability, validity and factor structure of the GDS‐15 in Iranian elderly. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2006; 21(6):588-93. [DOI:10.1002/gps.1533] [PMID]

- Soltaninejad H, Taghizadeh G, Habibi SAH, Bayat M, Fendereski F, Akbari R, et al. Validity and reliability of the Persian version of the geriatric depression scale-15 in older adults with parkinson’s disease. Applied Neuropsychology: Adult. 2025; 1-8. [DOI:10.1080/23279095.2025.2547311]

- Kang HJ, Bae KY, Kim SW, Shin HY, Shin IS, Yoon JS, et al. Impact of anxiety and depression on physical health condition and disability in an elderly Korean population. Psychiatry Investigation. 2017; 14(3):240-8. [DOI:10.4306/pi.2017.14.3.240] [PMID]

- Feng Z, Li Q, Zhou L, Chen Z, Yin W. The relationship between depressive symptoms and activity of daily living disability among the elderly: results from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). Public Health. 2021; 198:75-81. [DOI:10.1016/j.puhe.2021.06.023] [PMID]

- Mohamadzadeh M, Rashedi V, Hashemi M, Borhaninejad V. [Relationship between activities of daily living and depression in older adults (Persian)]. Salmand. 2020; 15(2):200-11. [DOI:10.32598/sija.13.10.180]

- karami N, Rezai J, Jozanifar Y, Abdi M, Aghaei A, Astanegi S, Karami M. [A survey of the depression rate among the elderly in Kermanshah, 2012(Persian)]. Journal of Clinical Research in Paramedical Sciences. 2016; 5(1):e81443. [Link]

- Mostfa MA, Mohamed NA. Depression, self-esteem and daily living activities among geriatric home residence people. Egyptian Journal of Health Care. 2019; 10(3):535-43. [DOI:10.21608/ejhc.2019.259466]

- Xue Y, Lu J, Zheng X, Zhang J, Lin H, Qin Z, et al. The relationship between socioeconomic status and depression among the older adults: the mediating role of health promoting lifestyle. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2021; 285:22-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2021.01.085] [PMID]

- Eylem O, de Wit L, van Straten A, Steubl L, Melissourgaki Z, Danışman GT, et al. Stigma for common mental disorders in racial minorities and majorities a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2020; 20(1):879. [DOI:10.1186/s12889-020-09199-y] [PMID]

- Patel R, Srivastava S, Kumar P, Chauhan S, Govindu M. Socio-economic inequality in functional disability and impairments with focus on instrumental activity of daily living: a study on older adults in India. BMC Public Health. 2021; 21(1):1541. [DOI:10.1186/s12889-021-11591-1] [PMID]

- Mobasseri K, Matlabi H, Allahverdipour H, Kousha A. Home-based supportive and health care services based on functional ability in older adults in Iran. Journal of Education and Health Promotion. 2024;13(1):124. [DOI:10.4103/jehp.jehp_422_23] [PMID]

- Hosseini S, Zabihi A, Jafarian Amiri S, Bijani A. [The relationship between chronic diseases and disability in daily activities and instrumental activities of daily living in the elderly(Persian)]. Journal of Babol University of Medical Sciences. 2018; 20(5):23-9. [DOI:10.18869/acadpub.jbums.20.5.23]

- Villarreal AE, Grajales S, López L, Oviedo DC, Carreira MB, Gómez LA, et al. Limitations in activities of daily living among dementia-free older adults in Panama. Ageing International. 2018; 43(2):237-53. [DOI:10.1007/s12126-018-9321-2]

- Burman J, Sembiah S, Dasgupta A, Paul B, Pawar N, Roy A. Assessment of poor functional status and its predictors among the elderly in a rural area of West Bengal. Journal of Mid-Life Health. 2019; 10(3):123-30. [DOI:10.4103/jmh.JMH_154_18] [PMID]

- Nakamura T, Michikawa T, Imamura H, Takebayashi T, Nishiwaki Y. Relationship between depressive symptoms and activity of daily living dependence in older Japanese: The Kurabuchi study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2017; 65(12):2639-45. [DOI:10.1111/jgs.15107] [PMID]

- Zhao Y, Huo X, Du H, Lai X, Li Z, Zhang Z, et al. Moderating effect of instrumental activities of daily living on the relationship between loneliness and depression in people with cognitive frailty. BMC geriatrics. 2025; 25(1):121. [DOI:10.1186/s12877-025-05700-7] [PMID]

- Yang F. Widowhood and loneliness among Chinese older adults: The role of education and gender. Aging & Mental Health. 2021; 25(7):1214-23. [DOI:10.1080/13607863.2020.1732293] [PMID]

- Yang H, Zheng X, Zhou R, Shen Z, Huang X. Fertility behavior and depression among women: Evidence from China. Frontiers in Psychology. 2020; 11:565508. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.565508] [PMID]

- Girgus JS, Yang K, Ferri CV. The gender difference in depression: Are elderly women at greater risk for depression than elderly men? Geriatrics. 2017; 2(4):35. [DOI:10.3390/geriatrics2040035] [PMID]

- Kundakovic M, Rocks D. Sex hormone fluctuation and increased female risk for depression and anxiety disorders: From clinical evidence to molecular mechanisms. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 2022; 66:101010. [DOI:10.1016/j.yfrne.2022.101010] [PMID]

- Srivastava S, Debnath P, Shri N, Muhammad T. The association of widowhood and living alone with depression among older adults in India. Scientific Reports. 2021; 11(1):21641. [DOI:10.1038/s41598-021-01238-x] [PMID]

- Papi S, Hosseini SV, Bahadori F, Rezapour V, Moghadasi AM, FadayeVatan R. Oral problems and psychological status of older adults referred to hospital and its relationship with cognition status, stress, anxiety, and depression. Iranian Journal of Health Sciences. 2022; 10(4):19-26. [DOI:10.32598/ijhs.10.4.909.1]

Type of Study: Original Article |

Subject:

Geriatrics

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |