Volume 13, Issue 3 (Summer 2025)

Iran J Health Sci 2025, 13(3): 203-212 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: IR.SSU.SPH.REC.1402.099

Clinical trials code: Not applicable

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Abbasi Shavazi M, Morowati Sharifabad M A, Jambarsang S, Rahimian M, Nasiri Z. Afghan Refugee Men’s Perspectives on Intimate Partner Violence Against Women: A Qualitative Study Using the PRECEDE-PROCEED Model. Iran J Health Sci 2025; 13 (3) :203-212

URL: http://jhs.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-1044-en.html

URL: http://jhs.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-1044-en.html

Masoumeh Abbasi Shavazi

, Mohammad Ali Morowati Sharifabad

, Mohammad Ali Morowati Sharifabad

, Sara Jambarsang

, Sara Jambarsang

, Mohammad Rahimian *

, Mohammad Rahimian *

, Zohreh Nasiri

, Zohreh Nasiri

, Mohammad Ali Morowati Sharifabad

, Mohammad Ali Morowati Sharifabad

, Sara Jambarsang

, Sara Jambarsang

, Mohammad Rahimian *

, Mohammad Rahimian *

, Zohreh Nasiri

, Zohreh Nasiri

Department of Health Education and Promotion, School of Public Health, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran. , rahimianm7@gmail.com

Full-Text [PDF 795 kb]

(449 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1206 Views)

Full-Text: (300 Views)

Introduction

Violence against women is a significant public health concern and a grave violation of human rights. The most prevalent form is intimate partner violence (IPV), often described as an epidemic—and sometimes even referred to as a silent epidemic [1-3]. One in three women experiences IPV at some point in their lives [1]. IPV profoundly affects women’s physical and mental health, leading to numerous adverse outcomes [1, 4]. It significantly heightens the risk of psychological disorders such as depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and suicidal ideation. Additionally, it contributes to challenges such as health complications, financial hardships, and housing instability [5]. Studies have identified factors driving men’s violence against women, including addiction, personality disorders, unmet needs, economic problems, negative beliefs about women, spousal conflicts, and age gaps [6-8]. Some men attempt to justify their violence against women in specific situations, such as perceived infidelity, acts of disobedience, or showing disrespect toward their parents and relatives [9]. Immigrant women, especially those affected by conflicts or displacement, face higher risks of IPV and are often unaware of support services or domestic violence laws, leading to low reporting rates [10-12]. Afghanistan, burdened by wars and cultural patriarchy, has one of the highest domestic violence rates in the world, with 90% of women experiencing IPV. These issues, accompanied by ongoing conflicts, famine, and drought, have led to widespread migration [13-17]. Afghan migrants and refugees often live in camps [18]. Iran serves as a primary refuge country for individuals escaping Afghanistan; however, most of them stay in the country for an extended duration. The second generation of children born to Afghan refugees in Iran now outnumbers the population of those originally born in Afghanistan [19]. Various theories and models have been implemented globally to address and mitigate IPV against women [20]. An influential and common model is the predisposing, reinforcing, and enabling constructs in educational diagnosis and evaluation - policy, regulatory, and organizational constructs in educational and environmental development (PRECEDE-PROCEED) model [21-23]. The predisposing, reinforcing, and enabling constructs within this model have been instrumental for over 30 years in advancing health programs, offering a robust theoretical framework for planning, implementing, and evaluating health promotion initiatives. This model seamlessly integrates policy, regulatory, and organizational dimensions into educational and environmental development efforts. Originally developed by Green, the PRECEDE component emphasizes health diagnosis and educational needs analysis, while the PROCEED component addresses policy, regulation, organizational dynamics, and environmental factors to underscore ecological influences. The model is structured into eight phases: Social assessment, epidemiological assessment, educational/ecological assessment, administrative/policy assessment and intervention planning, implementation, process evaluation, impact evaluation, and outcome evaluation. This comprehensive and phased approach enables the creation and execution of highly effective health promotion programs [24]. A significant number of studies have employed the PRECEDE-PROCEED model mainly during the planning, implementation, and evaluation phases of diverse health promotion programs across different populations and settings [25-27].

Considering the elevated incidence of IPV among female Afghan immigrants and the significant population of Afghan immigrants residing in Iran, this study aims to elucidate the perspectives of Afghan men residing in Torbat-E Jam Refugee Camp, regarding the factors contributing to IPV against women, utilizing the constructs of the PRECED-PROCEED model. The Torbat-E Jam Refugee Camp, located 10 kilometers from Torbat Jam city in Iran and 120 kilometers from the center of Khorasan province, has been operational since 1994. This facility accommodates approximately 5,000 Afghan refugees, providing them with housing and essential services. Spanning an area of 1,000,000 square meters (100 hectares), the camp is equipped with administrative offices, healthcare clinics, educational institutions, residential units, a commercial marketplace, and self-employment workshops [28]. It is anticipated that the findings will contribute to the development of targeted interventions and policies aimed at addressing gender-based violence within refugee communities. Furthermore, given the shared cultural and geographical ties between Torbat Jam city and Afghanistan, these insights may serve as a valuable resource for broader applications within Iranian society, fostering cross-border collaboration in tackling this critical issue.

Materials and Methods

This is a qualitative phenomenological study using a thematic analysis approach that was conducted on Afghan men residing in Torbat-E Jam Refugee Camp with a documented history of spousal abuse in the past two months. Participants were selected using a purposive sampling method to capture diverse age ranges, age gaps between spouses, and varying durations of residence in Iran. The sampling was continued until theoretical saturation, i.e. no new information was obtained [29]. In this study, theoretical saturation was reached after interviewing 17 individuals. Their lived experiences were surveyed through in-depth, face-to-face semi-structured interviews. These interviews took place in a private and secure room in a clinic of the camp. The questions were formulated after a pilot study to ensure their precision and relevance to the study objectives. Core questions included:

Can you share your experiences of engaging in violent behavior against your wife? How do you usually feel when you act violently against your wife? Based on your personal experience, what kinds of situations or factors drive you to have violent behavior against your wife? From your perspective, what circumstances or influences have helped or could help you reduce violent behavior against your wife? Is there anything else that you think is important to share with us?

Interviews, lasting for 20-45 minutes, were audio-recorded in addition to field note-taking with the informed consent of participants, and transcribed verbatim on the same day to ensure accuracy and preserve contextual detail. The participants’ demographic information was also collected. Additional questions emerged during the interviews, influenced by initial answers, developing thematic patterns, and the research objectives.

To analyze the content, thematic analysis was used, which is a widely utilized technique in qualitative research, enabling the identification, analysis, and reporting of patterns or themes within the data. This method provides researchers with valuable insights into the key concepts and overarching themes embedded in the data [30]. It is a flexible approach that can be applied using either inductive (data-driven) or deductive (theory-driven) methods [31]. For this study, a deductive approach was taken, utilizing the constructs of the PRECEDE-PROCEED model. The analysis was performed in MAXQDA software, version 18. The analysis involved a systematic line-by-line review of each transcript, identification of key words and phrases, development of succinct codes, and subsequent categorization of these codes within the framework of the PRECEDE-PROCEED model. Specifically, codes were first grouped into relevant subcategories aligned with the model’s constructs, and then these subcategories were organized under the main categories of predisposing, enabling, and reinforcing factors.

The trustworthiness of the data was assessed using Lincoln and Guba’s four criteria: Dependability, credibility, confirmability, and transferability [31]. To determine dependability, the duration of data collection (i.e. interviews) was minimized to reduce participant fatigue and ensure consistency. All participants were asked a standardized set of guiding questions related to the study topic. The research procedures and methods were explicitly and systematically documented. In addition, data were periodically reviewed by the research team to ensure coherence and alignment with the study objectives. To determine credibility, participants were invited to review the transcripts and the corresponding extracted codes, providing feedback on their accuracy and intended meaning (member checking). Purposeful sampling aimed at maximizing diversity was employed, and the research process involved prolonged engagement with the data and continuous immersion to enhance depth and authenticity of interpretation. To establish confirmability, the research process and analytical procedures were shared with colleagues for methodological verification. Furthermore, transcripts and their associated codes were independently reviewed by academic experts with expertise in qualitative research to assess the integrity and consistency of the coding process. To support transferability, rich and detailed descriptions of participants’ demographics, data collection strategies, and analytic procedures were provided. Illustrative quotations from participants were also included, allowing readers and future researchers to assess the relevance and applicability of the findings to other contexts.

Results

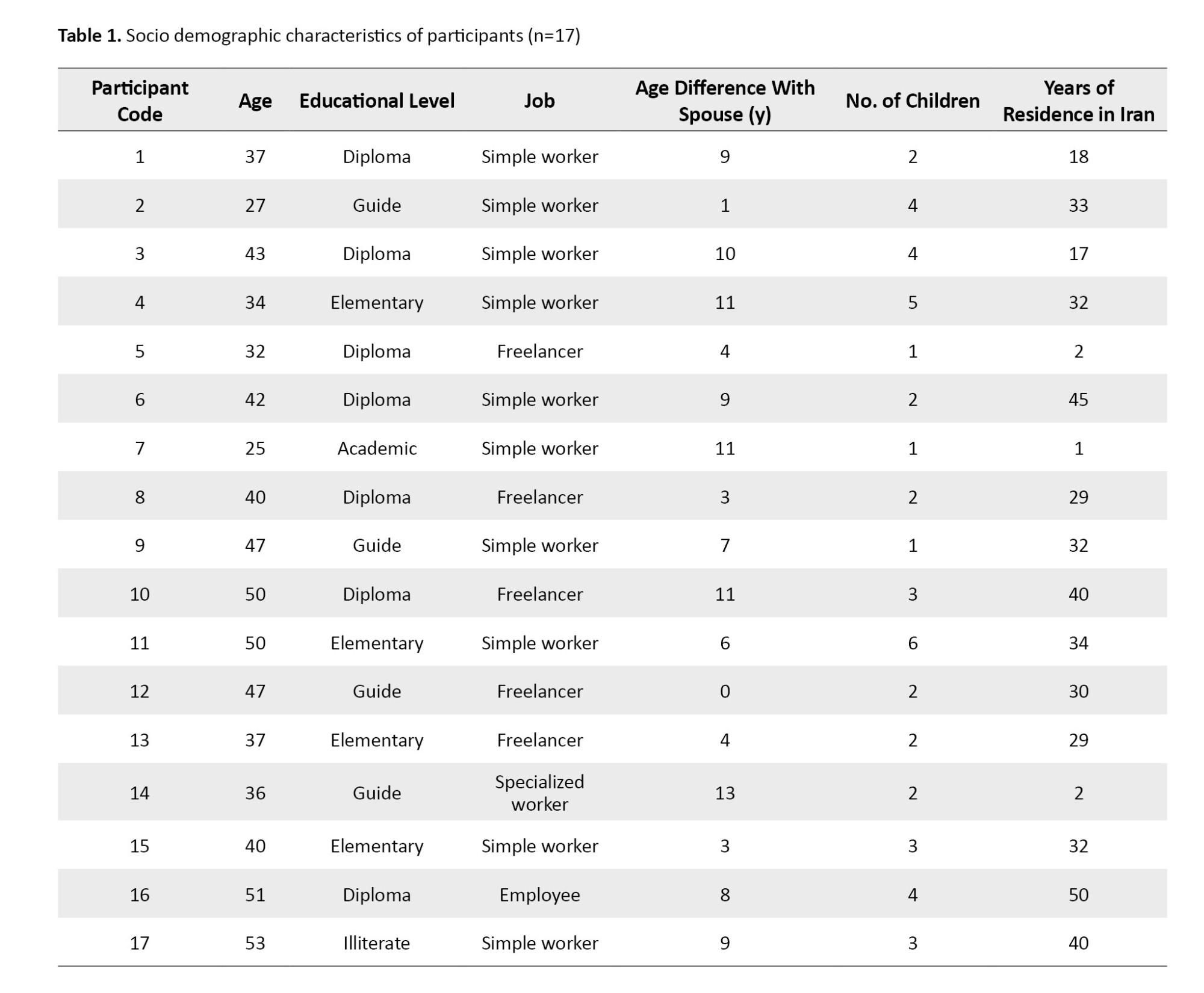

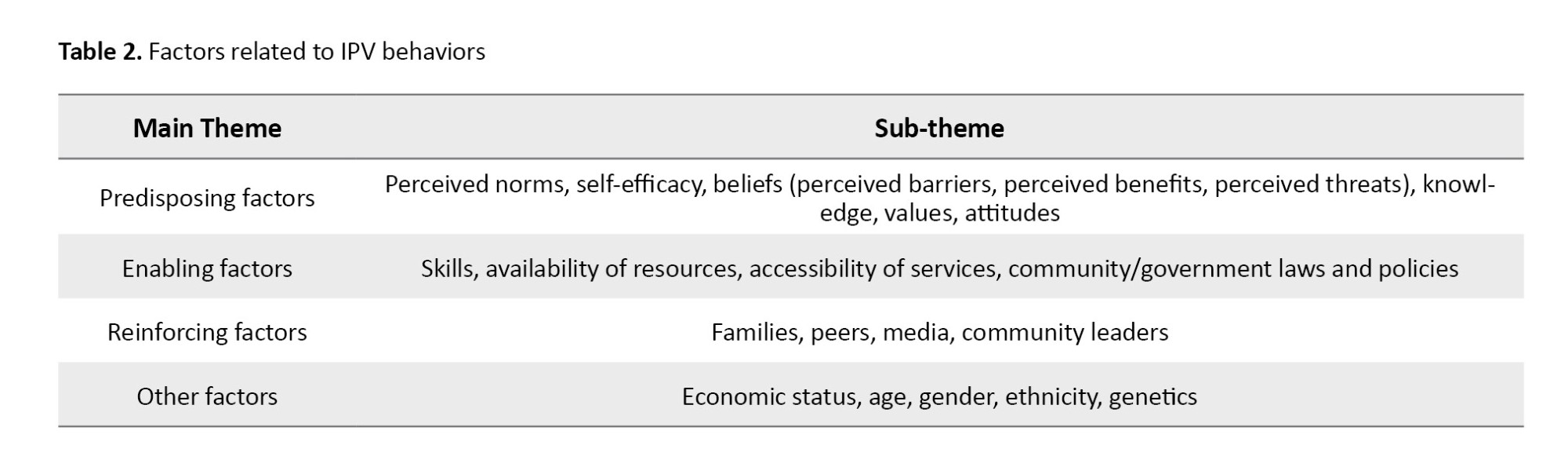

A total of 17 Afghan men participated in the study, with a mean age of 40.6±8.1 years. The majority of them (53%) had primary or secondary education and were simple workers (Table 1).

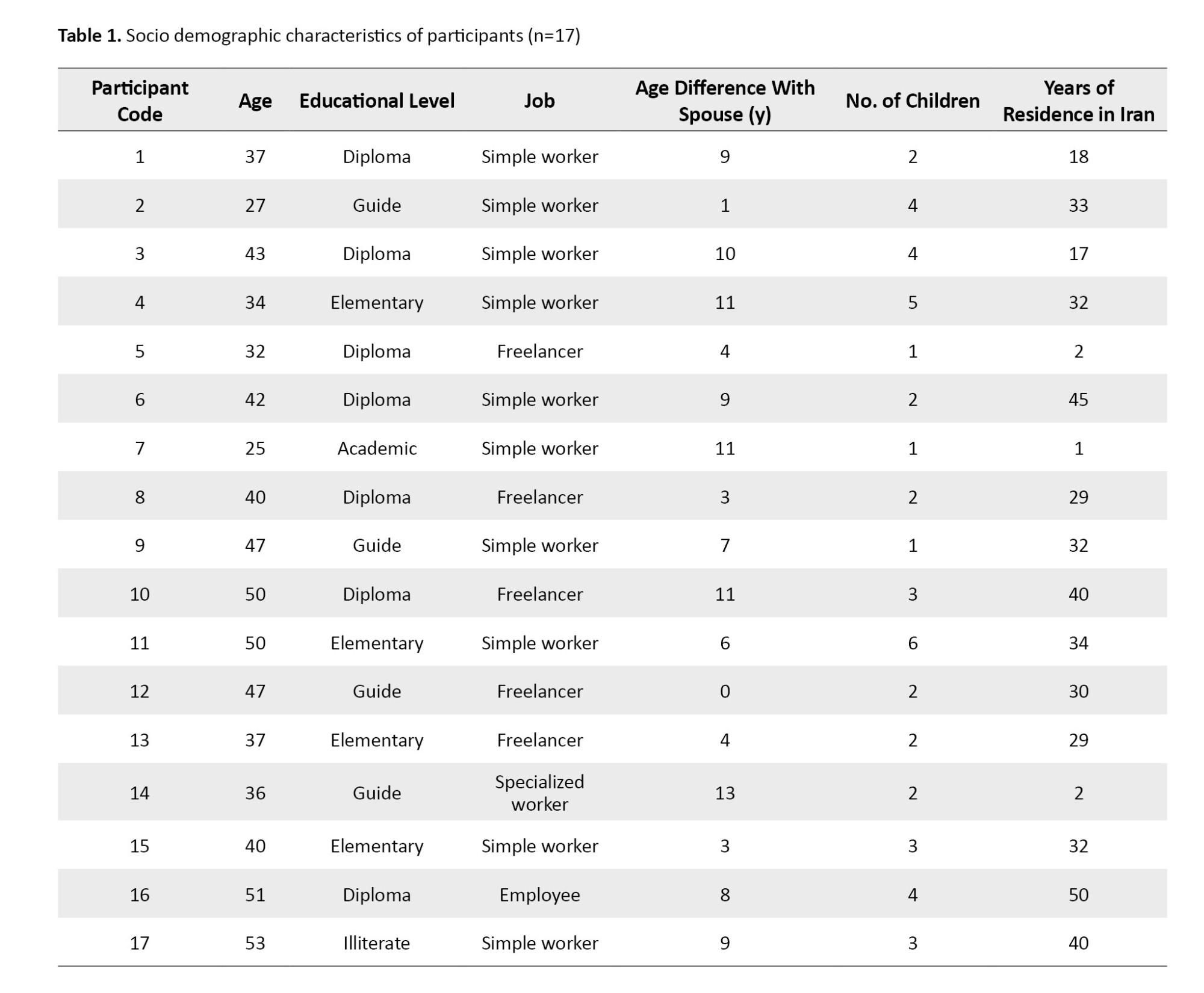

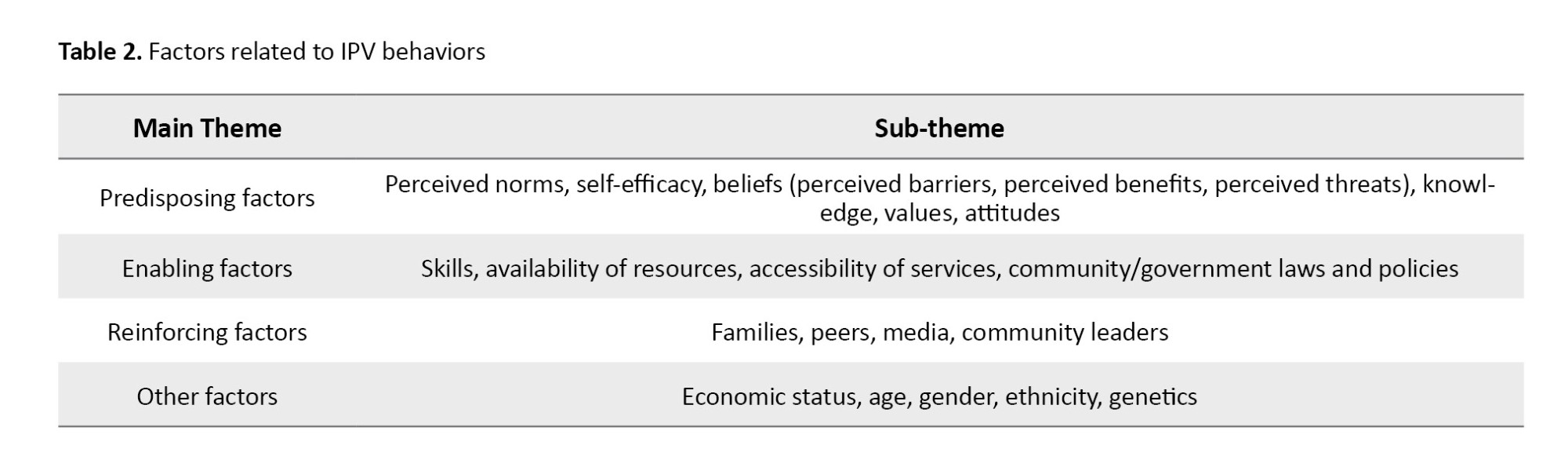

A total of 328 codes were extracted, categorized into four main themes (predisposing, enabling, reinforcing, other factors) and 21 sub-themes. Of the 328 codes, 252 were related to the predisposing factors, 24 to the enabling factors, 3 to the reinforcing factors, and 49 to other factors (Table 2).

Predisposing factors

Predisposing factors are characteristics or conditions that make an individual more susceptible to developing a specific problem, such as a disease, behavior, or condition [24]. This theme included perceived norms, self-efficacy, beliefs (perceived barriers, perceived benefits, perceived threats), knowledge, values, and attitudes.

Perceived norms

Perceived norms refer to individuals’ beliefs regarding what significant others approve or disapprove of, or perceptions of what peers typically do [32].

Witnessing violence in the parental family: Reports from men revealed witnessing paternal violence against mothers, which may establish behavioral patterns of either perpetrating or tolerating violence: “My father had a volatile temper and often found excuses to mistreat my mother. Whenever my brothers and I tried to step in, he would stop us.” (Participant No. 14 [P. 14]). “My father frequently abused and insulted my mother, creating a tense and hostile environment at home. The constant arguments and negativity left a lasting impact on our family, shaping much of my childhood experience” (P. 12).

Interference of others: The encouragement and involvement of others, especially family members, were identified as key factors predisposing Afghan men to engage in violent acts: “The influence of people around is also significant, with mothers-in-law often intervening. My mother tends to intervene sometimes” (P. 9). “Another concern is family culture, where parents tend to be nurturing and supportive but often end up interfering, even if they don’t recognize or admit it” (P. 7).

Self-efficacy

Self-efficacy, a key determinant of behavior, focuses on empowering individuals with a sense of control over their health. Rooted in Bandura’s social learning theory, it highlights an individual’s cognitive perception of control, where they feel confident in influencing their environment and taking purposeful action [32]. “After a tiring day at work, when I come home, I feel exhausted sometimes. Even if she says something upsetting, I try to stay calm” (P. 13). “I persuaded myself to avoid violence because the more I resorted to it, the worse the situation became instead of improving” (P. 9).

Beliefs

Belief refers to the conviction of the truth or reality of a phenomenon or object [32]. This sub-theme included the following components:

Perceived barriers: Factors such as the divorce stigma, fear of social disgrace, significant age gaps between spouses, familial marriages, lack of mutual understanding, absence of harmony, and challenges in child-rearing have emerged as barriers to adopting solutions or addressing violence: “Another concern is unmet sexual needs. If these needs are not addressed, it may result in frustration for the man, potentially leading to impatience and harmful behaviors such as lashing out at others, including the child or spouse” (P. 9). “Nowadays, some women may not feel motivated to wake up early to prepare breakfast if they gave a disagreement or conflict with their husbands” (P. 8).

Perceived benefits: Key benefits of managing and reducing violent behaviors include enhanced self-esteem, mutual respect, fewer challenges, improved living conditions, positive behavioral influences on children, future reflection of constructive behaviors, avoiding the negative consequences of violence, and increased marital satisfaction: “It is important to teach children to respect their elders, as this will encourage them to care for their parents when they grow older” (P. 4). “The more I resorted to violence, the worse things became instead of improving. Now I understand that violence leads to nothing” (P. 8).

Perceived threats: Perceived threats included fears of loneliness, impacts on children’s behavior, financial challenges, harm to male pride, and the influence of parental behavior on children: “When a man’s pride and passion are shattered moment by moment and day by day, nothing will be left for him” (P. 17). “Disrespecting her mother-in-law can teach the children not to respect their grandmother” (P. 4).

Knowledge

Knowledge is a fundamental component in the majority of theories [33], This study emphasized key areas of knowledge, including understanding the causes of violence, recognizing its various forms, identifying necessary actions during violent situations, and addressing the conditions that enable violence: “I’ve been married twice. My parents arranged the first marriage when I was away. The second marriage was more about convenience than anything else” (P. 17). “My wife and I are cousins, and our marriage followed a traditional path, arranged at the insistence of our fathers” (P. 6).

Values

Values are principles or beliefs that people consider significant. They are shaped by factors such as gender, culture, social affiliations, religion, and personal experiences. Once internalized, values influence motivations, thoughts, and actions, becoming a core part of an individual’s identity. They act as benchmarks for decision-making and provide a foundation for morally or ethically justifying one’s behavior [32]. The study highlighted key values, including expectations of a spouse, responses to a spouse’s behavior, children’s relationships with their fathers after violence, the balance between work and family roles, and the importance of a man’s active participation in family activities: “Being the youngest child in my family, I made it clear to my wife from the start of our marriage that it was my duty to support and care for my parents” (P. 4). “If a woman focuses on her own desires and maintains her independence, she will never face violence or abuse from his husband” (P. 12).

Attitudes

In health promotion planning, attitudes refer to value judgment of a specific behavior or task. These attitudes can vary from positive to negative and are generally shaped by internal values and beliefs developed over time [32]. “I love my wife, but women these days can become rude when they know they’re truly loved” (P. 3). “If you’re a good woman, why should I go after other women? You should know how to keep your husband” (P. 14).

Enabling factors

Enabling factors directly or indirectly influence behaviour through environmental mediators, encompassing skills, plans, and the availability/accessibility of essential resources [34]. This theme included skills, availability of resources, accessibility of services, community/government laws and policies.

Skills

Skills are an individual’s ability to perform tasks effectively. Health-promoting skills encompass controlling personal risk factors for diseases, effectively utilizing medical care, and managing or modifying environmental exposures [32, 35]. “Most of us here, including myself, were never taught how to treat a woman or have a wife” (P. 7). “When I’m under high pressure, I struggle to control my anger and often end up yelling and screaming” (P. 5).

Availability of resources

Easily accessible services are more likely to be used [35]. “I recommend focusing on the men who are currently neglected” (P. 17). “If there were a court or place to vent our emotions, it could really help“ (P. 8).

Accessibility of services

Services become less valuable when waitlists extend for years or are inaccessible to those in need [35]. “Having a doctor available here would be beneficial, as leaving the camp is both challenging and exhausting” (P. 13). “I urge authorities and families to thoroughly investigate when a woman with teary eyes reports her problems with her husband, rather than making judgments solely based on her tears” (P. 17).

Community/government laws and policies

Government laws and policies can both initiate changes in behaviour or the environment, and can be shaped by these changes [35]. “Thankfully, women are now gaining attention from the authorities. However, even when police or authorities support women, unfortunately, violence continues to rise” (P. 17).

Reinforcing factors

Reinforcing factors are the attitudes of both people and society that either encourage or impede the adoption of healthy behaviors and/or the establishment of healthy environmental conditions. These influential attitudes come from various sources, including families, peers, teachers, employers, healthcare or human service providers, media, community leaders, policymakers, and other decision-makers [35]. “My siblings are urging me to end my marriage. They believe that I deserve happiness and that my current relationship is causing harm and is not good for me! I’m trying to figure out what is best for my future” (P. 9).

Other factors

Various factors, such as personality and sociocultural components such as economic status, age, gender, ethnicity, genetics, and family size or history, can influence health-related behaviors or conditions through different mechanisms. Although these factors are considered “determinants” of behaviors and health outcomes, they are not categorized as predisposing, reinforcing, or enabling factors because they are not easily modifiable and do not directly support health promotion interventions. However, they are valuable in identifying groups that may require intervention and in determining whether distinct interventions are necessary for different groups. This information is vital in the early planning stages to pinpoint priority populations and assess the need for targeted communication or strategies [32]. “In Afghanistan, lives are unstable, exposed to violence both outside and within families. Since the Taliban’s takeover, the life challenges have been intensified, exacerbating the country’s issues and causing widespread suffering among its people” (P. 16). “Unemployment can lead to frustration and anger, contributing to IPV” (P. 11)

Discussion

The purpose of this research was to explore male Afghan refugees’ perspectives on IPV against women, who were living in refugee camp in Iran. This research surveys their living experiences, highlighting their personal experiences, sociocultural beliefs, and perceived influencing factors. Consequently, three primary themes emerged, including predisposing factors, enabling factors, and reinforcing factors.

In this study, the constructs of the PRECEDE-PROCEED model effectively elucidated the behaviors associated with IPV against women, aligning with the findings of Ekhtiari et al. [21]. In the study conducted by El-Kest et al. numerous behaviors related to domestic violence among adolescent girls were identified using the constructs of this model. These behaviors were subsequently improved through an intervention program based on the model’s constructs [23]. In our study, participants identified several predisposing factors that facilitate IPV, including the observation of paternal violence within the family, which aligns with the findings of Shaikh [36]. The intergenerational transmission of violence suggests that the tendency to engage in IPV stems from early dysfunction within the family system. Women from the families where fathers are violent toward mothers often internalize the belief that male violence against women and societal tolerance of such behavior are normal and expected [37]. Some participants in our study reported that their fathers were violent towards their mothers and likely mirrored their parents’ behavior. This is consistent with the findings of Azadeh and Dehghanfard [38]. Social learning theory suggests that children exposed to parental aggression may perceive violence as a good method for resolving conflicts. Over time, this belief can shape their understanding of interpersonal dynamics, potentially leading them to replicate similar behaviors in their own relationships. Furthermore, repeated exposure to parental aggression may normalize violent responses, diminishing their ability to develop healthier strategies for conflict resolution. This cycle can perpetuate across generations, emphasizing the critical need for positive role modeling and intervention to break the pattern [39, 40].

We identified unemployment and adverse economic conditions (non-behavioral factors) as key factors linked to IPV, consistent with the findings of Capaldi et al. [41]. Another study also highlighted that low income and unemployment are significant risk factors for IPV [37]. Poverty impacts individual health, particularly in impoverished and marginalized communities where access to healthcare is limited and gender inequality is pervasive. In these areas, women are often viewed as second-class citizens, leading to a higher prevalence of IPV against them. Unmet personal expectations and demands, such as sexual dissatisfaction or wife’s inability to cook meals (common examples of male dominance) were reported by Afghan men as reasons for IPV, a behavior that has also been analyzed and confirmed in other studies [42, 43]. Shinwari et al.’s study in Afghanistan demonstrated that defying gender norms and resisting men’s demands frequently exposes women to physical violence. Actions such as leaving the house without the husband’s permission, arguing with the husband, refusing to have sex, or even burning foods are often perceived as justifiable reasons for such violence against women [17]. In Muslim societies, patriarchal norms are prevalent and can sometimes be exploited to justify violence against women [16]. In many cultures, women are often regarded as subordinates to men or as a physically weaker gender, a perception deeply embedded in societal norms. This belief frequently leads men to view themselves as a superior gender, fostering conditions that allow them to gain advantages in various situations and contribute to an environment that perpetuates violence against women [44].

Conclusion

The findings of this study indicate that there are predisposing, enabling, and reinforcing factors that play a significant role in shaping Afghan men’s violent behaviors toward women. By implementing well-designed interventions, many of these factors—rooted primarily in cultural, social, and familial contexts—can be effectively addressed. Addressing these issues through economic empowerment, psychosocial support, and accessible resources is crucial. By modifying these factors, Afghan society can move toward a more harmonious environment, where women are empowered to thrive and fulfill their roles as mothers and wives without the burden of stress or fear. Without intervention, the consequences may deepen, leaving a lasting impact on women and perpetuating systemic gender inequalities. Systemic gender inequality not only restricts Afghan women’s access to opportunities but also actively perpetuates harmful stereotypes that impede meaningful progress toward gender equality. These biases, once normalized, become embedded in the fabric of everyday life, influencing how women are perceived and treated not only in professional environments and public spaces but also at home. It is imperative that Afghan authorities critically examine and reshape prevailing societal norms, invest in comprehensive gender equity education, and implement policies that safeguard Afghan women’s rights while enabling them to realize their full potential across all sectors of society. Only through such sustained and systemic efforts can we hope to cultivate a more just and inclusive future.

Limitations

This study had some limitations. First, the population was restricted to residents of the Torbat-E Jam Refugee Camp, which may limit the generalizability of the insights to other refugee camps in Iran or to all refugees. While qualitative studies prioritize transferability over generalizability, the concepts and themes identified here are intended to inform future research rather than serve as a prescriptive model.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran (Code: IR.SSU.SPH.REC.1402.099). All procedures adhere to the Declaration of Helsinki. All ethical principles, including voluntary participation, informed consent, anonymity, and confidentiality, were considered in this study.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection and analysis, interpretation of the results, and drafting of the manuscript. Each author approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Torbat-e Jam University of Medical Sciences, Torbat-e Jam, Iran, as well as the chief and staff of Torbat-e Jam Refuge Camp, for their cooperation in this project.

References

Violence against women is a significant public health concern and a grave violation of human rights. The most prevalent form is intimate partner violence (IPV), often described as an epidemic—and sometimes even referred to as a silent epidemic [1-3]. One in three women experiences IPV at some point in their lives [1]. IPV profoundly affects women’s physical and mental health, leading to numerous adverse outcomes [1, 4]. It significantly heightens the risk of psychological disorders such as depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and suicidal ideation. Additionally, it contributes to challenges such as health complications, financial hardships, and housing instability [5]. Studies have identified factors driving men’s violence against women, including addiction, personality disorders, unmet needs, economic problems, negative beliefs about women, spousal conflicts, and age gaps [6-8]. Some men attempt to justify their violence against women in specific situations, such as perceived infidelity, acts of disobedience, or showing disrespect toward their parents and relatives [9]. Immigrant women, especially those affected by conflicts or displacement, face higher risks of IPV and are often unaware of support services or domestic violence laws, leading to low reporting rates [10-12]. Afghanistan, burdened by wars and cultural patriarchy, has one of the highest domestic violence rates in the world, with 90% of women experiencing IPV. These issues, accompanied by ongoing conflicts, famine, and drought, have led to widespread migration [13-17]. Afghan migrants and refugees often live in camps [18]. Iran serves as a primary refuge country for individuals escaping Afghanistan; however, most of them stay in the country for an extended duration. The second generation of children born to Afghan refugees in Iran now outnumbers the population of those originally born in Afghanistan [19]. Various theories and models have been implemented globally to address and mitigate IPV against women [20]. An influential and common model is the predisposing, reinforcing, and enabling constructs in educational diagnosis and evaluation - policy, regulatory, and organizational constructs in educational and environmental development (PRECEDE-PROCEED) model [21-23]. The predisposing, reinforcing, and enabling constructs within this model have been instrumental for over 30 years in advancing health programs, offering a robust theoretical framework for planning, implementing, and evaluating health promotion initiatives. This model seamlessly integrates policy, regulatory, and organizational dimensions into educational and environmental development efforts. Originally developed by Green, the PRECEDE component emphasizes health diagnosis and educational needs analysis, while the PROCEED component addresses policy, regulation, organizational dynamics, and environmental factors to underscore ecological influences. The model is structured into eight phases: Social assessment, epidemiological assessment, educational/ecological assessment, administrative/policy assessment and intervention planning, implementation, process evaluation, impact evaluation, and outcome evaluation. This comprehensive and phased approach enables the creation and execution of highly effective health promotion programs [24]. A significant number of studies have employed the PRECEDE-PROCEED model mainly during the planning, implementation, and evaluation phases of diverse health promotion programs across different populations and settings [25-27].

Considering the elevated incidence of IPV among female Afghan immigrants and the significant population of Afghan immigrants residing in Iran, this study aims to elucidate the perspectives of Afghan men residing in Torbat-E Jam Refugee Camp, regarding the factors contributing to IPV against women, utilizing the constructs of the PRECED-PROCEED model. The Torbat-E Jam Refugee Camp, located 10 kilometers from Torbat Jam city in Iran and 120 kilometers from the center of Khorasan province, has been operational since 1994. This facility accommodates approximately 5,000 Afghan refugees, providing them with housing and essential services. Spanning an area of 1,000,000 square meters (100 hectares), the camp is equipped with administrative offices, healthcare clinics, educational institutions, residential units, a commercial marketplace, and self-employment workshops [28]. It is anticipated that the findings will contribute to the development of targeted interventions and policies aimed at addressing gender-based violence within refugee communities. Furthermore, given the shared cultural and geographical ties between Torbat Jam city and Afghanistan, these insights may serve as a valuable resource for broader applications within Iranian society, fostering cross-border collaboration in tackling this critical issue.

Materials and Methods

This is a qualitative phenomenological study using a thematic analysis approach that was conducted on Afghan men residing in Torbat-E Jam Refugee Camp with a documented history of spousal abuse in the past two months. Participants were selected using a purposive sampling method to capture diverse age ranges, age gaps between spouses, and varying durations of residence in Iran. The sampling was continued until theoretical saturation, i.e. no new information was obtained [29]. In this study, theoretical saturation was reached after interviewing 17 individuals. Their lived experiences were surveyed through in-depth, face-to-face semi-structured interviews. These interviews took place in a private and secure room in a clinic of the camp. The questions were formulated after a pilot study to ensure their precision and relevance to the study objectives. Core questions included:

Can you share your experiences of engaging in violent behavior against your wife? How do you usually feel when you act violently against your wife? Based on your personal experience, what kinds of situations or factors drive you to have violent behavior against your wife? From your perspective, what circumstances or influences have helped or could help you reduce violent behavior against your wife? Is there anything else that you think is important to share with us?

Interviews, lasting for 20-45 minutes, were audio-recorded in addition to field note-taking with the informed consent of participants, and transcribed verbatim on the same day to ensure accuracy and preserve contextual detail. The participants’ demographic information was also collected. Additional questions emerged during the interviews, influenced by initial answers, developing thematic patterns, and the research objectives.

To analyze the content, thematic analysis was used, which is a widely utilized technique in qualitative research, enabling the identification, analysis, and reporting of patterns or themes within the data. This method provides researchers with valuable insights into the key concepts and overarching themes embedded in the data [30]. It is a flexible approach that can be applied using either inductive (data-driven) or deductive (theory-driven) methods [31]. For this study, a deductive approach was taken, utilizing the constructs of the PRECEDE-PROCEED model. The analysis was performed in MAXQDA software, version 18. The analysis involved a systematic line-by-line review of each transcript, identification of key words and phrases, development of succinct codes, and subsequent categorization of these codes within the framework of the PRECEDE-PROCEED model. Specifically, codes were first grouped into relevant subcategories aligned with the model’s constructs, and then these subcategories were organized under the main categories of predisposing, enabling, and reinforcing factors.

The trustworthiness of the data was assessed using Lincoln and Guba’s four criteria: Dependability, credibility, confirmability, and transferability [31]. To determine dependability, the duration of data collection (i.e. interviews) was minimized to reduce participant fatigue and ensure consistency. All participants were asked a standardized set of guiding questions related to the study topic. The research procedures and methods were explicitly and systematically documented. In addition, data were periodically reviewed by the research team to ensure coherence and alignment with the study objectives. To determine credibility, participants were invited to review the transcripts and the corresponding extracted codes, providing feedback on their accuracy and intended meaning (member checking). Purposeful sampling aimed at maximizing diversity was employed, and the research process involved prolonged engagement with the data and continuous immersion to enhance depth and authenticity of interpretation. To establish confirmability, the research process and analytical procedures were shared with colleagues for methodological verification. Furthermore, transcripts and their associated codes were independently reviewed by academic experts with expertise in qualitative research to assess the integrity and consistency of the coding process. To support transferability, rich and detailed descriptions of participants’ demographics, data collection strategies, and analytic procedures were provided. Illustrative quotations from participants were also included, allowing readers and future researchers to assess the relevance and applicability of the findings to other contexts.

Results

A total of 17 Afghan men participated in the study, with a mean age of 40.6±8.1 years. The majority of them (53%) had primary or secondary education and were simple workers (Table 1).

A total of 328 codes were extracted, categorized into four main themes (predisposing, enabling, reinforcing, other factors) and 21 sub-themes. Of the 328 codes, 252 were related to the predisposing factors, 24 to the enabling factors, 3 to the reinforcing factors, and 49 to other factors (Table 2).

Predisposing factors

Predisposing factors are characteristics or conditions that make an individual more susceptible to developing a specific problem, such as a disease, behavior, or condition [24]. This theme included perceived norms, self-efficacy, beliefs (perceived barriers, perceived benefits, perceived threats), knowledge, values, and attitudes.

Perceived norms

Perceived norms refer to individuals’ beliefs regarding what significant others approve or disapprove of, or perceptions of what peers typically do [32].

Witnessing violence in the parental family: Reports from men revealed witnessing paternal violence against mothers, which may establish behavioral patterns of either perpetrating or tolerating violence: “My father had a volatile temper and often found excuses to mistreat my mother. Whenever my brothers and I tried to step in, he would stop us.” (Participant No. 14 [P. 14]). “My father frequently abused and insulted my mother, creating a tense and hostile environment at home. The constant arguments and negativity left a lasting impact on our family, shaping much of my childhood experience” (P. 12).

Interference of others: The encouragement and involvement of others, especially family members, were identified as key factors predisposing Afghan men to engage in violent acts: “The influence of people around is also significant, with mothers-in-law often intervening. My mother tends to intervene sometimes” (P. 9). “Another concern is family culture, where parents tend to be nurturing and supportive but often end up interfering, even if they don’t recognize or admit it” (P. 7).

Self-efficacy

Self-efficacy, a key determinant of behavior, focuses on empowering individuals with a sense of control over their health. Rooted in Bandura’s social learning theory, it highlights an individual’s cognitive perception of control, where they feel confident in influencing their environment and taking purposeful action [32]. “After a tiring day at work, when I come home, I feel exhausted sometimes. Even if she says something upsetting, I try to stay calm” (P. 13). “I persuaded myself to avoid violence because the more I resorted to it, the worse the situation became instead of improving” (P. 9).

Beliefs

Belief refers to the conviction of the truth or reality of a phenomenon or object [32]. This sub-theme included the following components:

Perceived barriers: Factors such as the divorce stigma, fear of social disgrace, significant age gaps between spouses, familial marriages, lack of mutual understanding, absence of harmony, and challenges in child-rearing have emerged as barriers to adopting solutions or addressing violence: “Another concern is unmet sexual needs. If these needs are not addressed, it may result in frustration for the man, potentially leading to impatience and harmful behaviors such as lashing out at others, including the child or spouse” (P. 9). “Nowadays, some women may not feel motivated to wake up early to prepare breakfast if they gave a disagreement or conflict with their husbands” (P. 8).

Perceived benefits: Key benefits of managing and reducing violent behaviors include enhanced self-esteem, mutual respect, fewer challenges, improved living conditions, positive behavioral influences on children, future reflection of constructive behaviors, avoiding the negative consequences of violence, and increased marital satisfaction: “It is important to teach children to respect their elders, as this will encourage them to care for their parents when they grow older” (P. 4). “The more I resorted to violence, the worse things became instead of improving. Now I understand that violence leads to nothing” (P. 8).

Perceived threats: Perceived threats included fears of loneliness, impacts on children’s behavior, financial challenges, harm to male pride, and the influence of parental behavior on children: “When a man’s pride and passion are shattered moment by moment and day by day, nothing will be left for him” (P. 17). “Disrespecting her mother-in-law can teach the children not to respect their grandmother” (P. 4).

Knowledge

Knowledge is a fundamental component in the majority of theories [33], This study emphasized key areas of knowledge, including understanding the causes of violence, recognizing its various forms, identifying necessary actions during violent situations, and addressing the conditions that enable violence: “I’ve been married twice. My parents arranged the first marriage when I was away. The second marriage was more about convenience than anything else” (P. 17). “My wife and I are cousins, and our marriage followed a traditional path, arranged at the insistence of our fathers” (P. 6).

Values

Values are principles or beliefs that people consider significant. They are shaped by factors such as gender, culture, social affiliations, religion, and personal experiences. Once internalized, values influence motivations, thoughts, and actions, becoming a core part of an individual’s identity. They act as benchmarks for decision-making and provide a foundation for morally or ethically justifying one’s behavior [32]. The study highlighted key values, including expectations of a spouse, responses to a spouse’s behavior, children’s relationships with their fathers after violence, the balance between work and family roles, and the importance of a man’s active participation in family activities: “Being the youngest child in my family, I made it clear to my wife from the start of our marriage that it was my duty to support and care for my parents” (P. 4). “If a woman focuses on her own desires and maintains her independence, she will never face violence or abuse from his husband” (P. 12).

Attitudes

In health promotion planning, attitudes refer to value judgment of a specific behavior or task. These attitudes can vary from positive to negative and are generally shaped by internal values and beliefs developed over time [32]. “I love my wife, but women these days can become rude when they know they’re truly loved” (P. 3). “If you’re a good woman, why should I go after other women? You should know how to keep your husband” (P. 14).

Enabling factors

Enabling factors directly or indirectly influence behaviour through environmental mediators, encompassing skills, plans, and the availability/accessibility of essential resources [34]. This theme included skills, availability of resources, accessibility of services, community/government laws and policies.

Skills

Skills are an individual’s ability to perform tasks effectively. Health-promoting skills encompass controlling personal risk factors for diseases, effectively utilizing medical care, and managing or modifying environmental exposures [32, 35]. “Most of us here, including myself, were never taught how to treat a woman or have a wife” (P. 7). “When I’m under high pressure, I struggle to control my anger and often end up yelling and screaming” (P. 5).

Availability of resources

Easily accessible services are more likely to be used [35]. “I recommend focusing on the men who are currently neglected” (P. 17). “If there were a court or place to vent our emotions, it could really help“ (P. 8).

Accessibility of services

Services become less valuable when waitlists extend for years or are inaccessible to those in need [35]. “Having a doctor available here would be beneficial, as leaving the camp is both challenging and exhausting” (P. 13). “I urge authorities and families to thoroughly investigate when a woman with teary eyes reports her problems with her husband, rather than making judgments solely based on her tears” (P. 17).

Community/government laws and policies

Government laws and policies can both initiate changes in behaviour or the environment, and can be shaped by these changes [35]. “Thankfully, women are now gaining attention from the authorities. However, even when police or authorities support women, unfortunately, violence continues to rise” (P. 17).

Reinforcing factors

Reinforcing factors are the attitudes of both people and society that either encourage or impede the adoption of healthy behaviors and/or the establishment of healthy environmental conditions. These influential attitudes come from various sources, including families, peers, teachers, employers, healthcare or human service providers, media, community leaders, policymakers, and other decision-makers [35]. “My siblings are urging me to end my marriage. They believe that I deserve happiness and that my current relationship is causing harm and is not good for me! I’m trying to figure out what is best for my future” (P. 9).

Other factors

Various factors, such as personality and sociocultural components such as economic status, age, gender, ethnicity, genetics, and family size or history, can influence health-related behaviors or conditions through different mechanisms. Although these factors are considered “determinants” of behaviors and health outcomes, they are not categorized as predisposing, reinforcing, or enabling factors because they are not easily modifiable and do not directly support health promotion interventions. However, they are valuable in identifying groups that may require intervention and in determining whether distinct interventions are necessary for different groups. This information is vital in the early planning stages to pinpoint priority populations and assess the need for targeted communication or strategies [32]. “In Afghanistan, lives are unstable, exposed to violence both outside and within families. Since the Taliban’s takeover, the life challenges have been intensified, exacerbating the country’s issues and causing widespread suffering among its people” (P. 16). “Unemployment can lead to frustration and anger, contributing to IPV” (P. 11)

Discussion

The purpose of this research was to explore male Afghan refugees’ perspectives on IPV against women, who were living in refugee camp in Iran. This research surveys their living experiences, highlighting their personal experiences, sociocultural beliefs, and perceived influencing factors. Consequently, three primary themes emerged, including predisposing factors, enabling factors, and reinforcing factors.

In this study, the constructs of the PRECEDE-PROCEED model effectively elucidated the behaviors associated with IPV against women, aligning with the findings of Ekhtiari et al. [21]. In the study conducted by El-Kest et al. numerous behaviors related to domestic violence among adolescent girls were identified using the constructs of this model. These behaviors were subsequently improved through an intervention program based on the model’s constructs [23]. In our study, participants identified several predisposing factors that facilitate IPV, including the observation of paternal violence within the family, which aligns with the findings of Shaikh [36]. The intergenerational transmission of violence suggests that the tendency to engage in IPV stems from early dysfunction within the family system. Women from the families where fathers are violent toward mothers often internalize the belief that male violence against women and societal tolerance of such behavior are normal and expected [37]. Some participants in our study reported that their fathers were violent towards their mothers and likely mirrored their parents’ behavior. This is consistent with the findings of Azadeh and Dehghanfard [38]. Social learning theory suggests that children exposed to parental aggression may perceive violence as a good method for resolving conflicts. Over time, this belief can shape their understanding of interpersonal dynamics, potentially leading them to replicate similar behaviors in their own relationships. Furthermore, repeated exposure to parental aggression may normalize violent responses, diminishing their ability to develop healthier strategies for conflict resolution. This cycle can perpetuate across generations, emphasizing the critical need for positive role modeling and intervention to break the pattern [39, 40].

We identified unemployment and adverse economic conditions (non-behavioral factors) as key factors linked to IPV, consistent with the findings of Capaldi et al. [41]. Another study also highlighted that low income and unemployment are significant risk factors for IPV [37]. Poverty impacts individual health, particularly in impoverished and marginalized communities where access to healthcare is limited and gender inequality is pervasive. In these areas, women are often viewed as second-class citizens, leading to a higher prevalence of IPV against them. Unmet personal expectations and demands, such as sexual dissatisfaction or wife’s inability to cook meals (common examples of male dominance) were reported by Afghan men as reasons for IPV, a behavior that has also been analyzed and confirmed in other studies [42, 43]. Shinwari et al.’s study in Afghanistan demonstrated that defying gender norms and resisting men’s demands frequently exposes women to physical violence. Actions such as leaving the house without the husband’s permission, arguing with the husband, refusing to have sex, or even burning foods are often perceived as justifiable reasons for such violence against women [17]. In Muslim societies, patriarchal norms are prevalent and can sometimes be exploited to justify violence against women [16]. In many cultures, women are often regarded as subordinates to men or as a physically weaker gender, a perception deeply embedded in societal norms. This belief frequently leads men to view themselves as a superior gender, fostering conditions that allow them to gain advantages in various situations and contribute to an environment that perpetuates violence against women [44].

Conclusion

The findings of this study indicate that there are predisposing, enabling, and reinforcing factors that play a significant role in shaping Afghan men’s violent behaviors toward women. By implementing well-designed interventions, many of these factors—rooted primarily in cultural, social, and familial contexts—can be effectively addressed. Addressing these issues through economic empowerment, psychosocial support, and accessible resources is crucial. By modifying these factors, Afghan society can move toward a more harmonious environment, where women are empowered to thrive and fulfill their roles as mothers and wives without the burden of stress or fear. Without intervention, the consequences may deepen, leaving a lasting impact on women and perpetuating systemic gender inequalities. Systemic gender inequality not only restricts Afghan women’s access to opportunities but also actively perpetuates harmful stereotypes that impede meaningful progress toward gender equality. These biases, once normalized, become embedded in the fabric of everyday life, influencing how women are perceived and treated not only in professional environments and public spaces but also at home. It is imperative that Afghan authorities critically examine and reshape prevailing societal norms, invest in comprehensive gender equity education, and implement policies that safeguard Afghan women’s rights while enabling them to realize their full potential across all sectors of society. Only through such sustained and systemic efforts can we hope to cultivate a more just and inclusive future.

Limitations

This study had some limitations. First, the population was restricted to residents of the Torbat-E Jam Refugee Camp, which may limit the generalizability of the insights to other refugee camps in Iran or to all refugees. While qualitative studies prioritize transferability over generalizability, the concepts and themes identified here are intended to inform future research rather than serve as a prescriptive model.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran (Code: IR.SSU.SPH.REC.1402.099). All procedures adhere to the Declaration of Helsinki. All ethical principles, including voluntary participation, informed consent, anonymity, and confidentiality, were considered in this study.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection and analysis, interpretation of the results, and drafting of the manuscript. Each author approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Torbat-e Jam University of Medical Sciences, Torbat-e Jam, Iran, as well as the chief and staff of Torbat-e Jam Refuge Camp, for their cooperation in this project.

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Violence against women. Geneva: WHO; 2024. [Link]

- Piccinini A, Bailo P, Barbara G, Miozzo M, Tabano S, Colapietro P, et al. Violence against women and stress-related disorders: Seeking for associated epigenetic signatures, A pilot study. Healthcare. 2023; 11(2):173. [DOI:10.3390/healthcare11020173] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Razaghi N, Parvizi s, Ramadani M, Tabatabai.Nejad SM. The consequences of violence against women in the family: A qualitative study. Iranian Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Infertility. 2013; 16(44):11-20. [Link]

- Hu R, Xue J, Wang X. Migrant women’s help-seeking decisions and use of support resources for intimate partner violence in China. Violence Against Women. 2022; 28(1):169-93. [DOI:10.1177/10778012211000133] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Chu YC, Wang HH, Chou FH, Hsu YF, Liao KL. Outcomes of trauma-informed care on the psychological health of women experiencing intimate partner violence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. 2024; 31(2):203-14. [DOI:10.1111/jpm.12976] [PMID]

- Hosseini SH, Mohseni RA, Firozjaeian AA. [The sociological explanation of violence against women (an experimental study) (Persian)]. Quarterly of Social Studies and Research in Iran. 2019; 8(2):411-32. [DOI: 10.22059/jisr.2019.250144.624]

- Hashemian M, Solhi M, Gharmaroudi G, Mehri A, Joveini H, Shahrabadi R. [Married men's experiences of domestic violence on their wives: A qualitative study (Persian)]. Journal of Qualitative Research in Health Sciences. 2018; 7(2):214-26. [Link]

- Ghazizadeh H, Zahrakar K, Kiamanesh A, Mohsenzadeh F. [Conceptual model of underlying factors in women domestic violence against men (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Psychiatric Nursing. 2018; 6(4):34-47. [DOI:10.21859/ijpn-06045]

- Aliverdinia A, Habibi M. [The study of university male students attitude toward violence against woman in family context: An empirical test of Akers social learning theory (Persian)]. Strategic Research on Social Problems in Iran. 2016; 4(3):15-38. [Link]

- Park T, Mullins A, Zahir N, Salami B, Lasiuk G, Hegadoren K. Domestic Violence And Immigrant Women: A glimpse behind a veiled door. Violence Against Women. 2021; 27(15-16):2910-26. [DOI:10.1177/1077801220984174] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Delkhosh M, Merghati Khoei E, Ardalan A, Rahimi Foroushani A, Gharavi MB. Prevalence of intimate partner violence and reproductive health outcomes among Afghan refugee women in Iran. Health care for Women International. 2019; 40(2):213-37. [DOI:10.1080/07399332.2018.1529766] [PMID]

- Dicola D, Spaar E. Intimate partner violence. American Family Physician. 2016; 94(8):646-51. [Link]

- Dashti Z. Afghan external migration movements in the historical process. Akademic Social Studies. 2022; 6(20):301-14. [DOI:10.31455/asya.1055791]

- Dadras O, Nakayama T, Kihara M, Ono-Kihara M, Dadras F. Intimate partner violence and unmet need for family planning in Afghan women: The implication for policy and practice. Reproductive Health. 2022; 19(1):52. [DOI:10.1186/s12978-022-01362-5] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Khatir AG, Ge T, Ariyo T, Jiang Q. Armed conflicts and experience of intimate partner violence among women in Afghanistan: Analysis of the 2015 Afghanistan DHS data. BMJ Open. 2024; 14(4):e075957. [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2023-075957] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Afrouz R, Crisp BR, Taket A. Seeking help in domestic violence among muslim women in muslim-majority and non-muslim-majority countries: A literature review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2020; 21(3):551-66. [DOI:10.1177/1524838018781102] [PMID]

- Shinwari R, Wilson ML, Abiodun O, Shaikh MA. Intimate partner violence among ever-married Afghan women: Patterns, associations and attitudinal acceptance. Archives of Women's Mental Health. 2022; 25(1):95-105. [DOI:10.1007/s00737-021-01143-2] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Khan A. Protracted Afghan refugee situation. Strategic Studies. 2017; 37(1):42-65. [DOI:10.53532/ss.037.01.00230]

- Hugo G, Abbasi-Shavazib MJ, Sadeghi R. Refugee movement and development-Afghan refugees in Iran. Migration and Development. 2012; 1(2):261-79. [DOI:10.1080/21632324.2012.749741]

- Abbasishavaz M, Morowati Sharifabad MA, Rahimian M, Jam-barsang S. Application of health education theories and models in intimate partner violence interventions against women in Iran: A review study. Journal of Research and Health. 2025; 15(3):217-26. [DOI:10.32598/JRH.15.3.1271.1]

- Ekhtiari YS, Shojaeizadeh D, Foroushani AR, Ghofranipour F, Ahmadi B. The effect of an intervention based on the PRECEDE-PROCEED model on preventive behaviors of domestic violence among Iranian high school girls. Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal. 2013; 15(1):21. [DOI:10.5812/ircmj.3517] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Rahimian M, Shavazi MA, Sharifabad MAM, Jam-Barsang S. Design, implementation, and evaluation of a PRECEDE-PROCEED model-based intervention to reduce Intimate Partner Violence against women in Afghan men living in refugee camp of Torbat Jam County (Iran): Protocol for an embedded study. 2024 [Unpublished]. [DOI:10.21203/rs.3.rs-4578090/v1]

- El-Kest HR, Fouda LM, Alhossiny EA, Khaton SE. The effect of an educational intervention program on prevention of domestic violence among adolescent girls. Journal of Nursing and Health Science. 2018; 7(3):73-88. [DOI:10.9790/1959-0703077382]

- Kim J, Jang J, Kim B, Lee KH. Effect of the PRECEDE-PROCEED model on health programs: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Systematic Reviews. 2022; 11(1):213. [DOI:10.1186/s13643-022-02092-2] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Solhi M, Shabani Hamedan M, Salehi M. A Precede-Proceed based educational intervention in quality of life of women-headed households in Iran. Medical Journal of the Islamic Republic of Iran. 2016; 30:417. [PMID]

- Moshki M, Dehnoalian A, Alami A. Effect of precede-proceed model on preventive behaviors for type 2 diabetes mellitus in high-risk individuals. Clinical Nursing Research. 2017; 26(2):241-53. [DOI:10.1177/1054773815621026] [PMID]

- Zendeh Talab HR. [The effect of a program designed based on PRECEDE-PROCEED model on adolescents’ mental health and their parents’ participation (Persian)]. Evidence Based Care Journal. 2012; 2(1):45-54. [DOI:10.22038/ebcj.2012.389]

- Torbat Jam Faculity of Medical Sciences. Providing health services to 11,000 people without birth certificates [Internet]. 2023 [Updated 2023 May 23]. Available from: [Link]

- Onwuegbuzie AJ, Leech NL. Sampling designs in qualitative research: Making the sampling process more public. Qualitative Report. 2007; 12(2):238-54. [DOI:10.46743/2160-3715/2007.1636]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006; 3(2):77-101. [DOI:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa]

- Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, Moules NJ. Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 2017; 16(1):1609406917733847. [DOI:10.1177/1609406917733847]

- Ottoson Judith M, Gielen A, Green Lawrence W, Kreuter Marshall W, Peterson Darleen V. Health program planning, implementation, and evaluation: Creating behavioral, environmental, and policy change/edited by Lawrence W. Green, Andrea Carlson Gielen, Judith M. Ottoson, Darleen V. Peterson, Marshall W. Kreuter; foreword by Jonathan E. Fielding. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2022. [Link]

- Langlois MA, Hallam JS. Integrating multiple health behavior theories into program planning: The PER worksheet. Health Promotion Practice. 2010; 11(2):282-8. [DOI:10.1177/1524839908317668] [PMID]

- Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice. 4, editor. New York: Jossey-Bass; 2008. [Link]

- University of Kansas. Community tool box. Section 2. PRECEDE/PROCEED [Internet] [Updated 2025 September 9]. Available from: [Link]

- Shaikh MA. Spousal violence against women in Afghanistan: Bivariate mapping of correlates. JPMA The Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association. 2022; 72(5):961-4. [DOI:10.47391/jpma.22-62] [PMID]

- Farahbod M, Masoudi Asl I, Tabibi SJ, Kamali M. [Comparing the rehabilitation structures in the health systems of Iran, Germany, Japan, Canada, Turkey, and South Africa (Persian)]. Archives of Rehabilitation. 2023; 24(1):96-113. [DOI:10.32598/rj.24.1.3582.1]

- Azam Azadeh M, Dehghanfard R. [Domestic violence on women in Tehran: the role of gender socialization, resources available for women and family relationships (Persian)]. Woman in Development and Politics Year. 2006; 4(1-2):159-79. [Link]

- Sellers CS, Cochran JK, Branch KA. Social learning theory and partner violence: A research note. Deviant Behavior. 2005; 26(4):379-95. [DOI:10.1080/016396290931669]

- Muniz CN, Zavala E. The influence of self-control on social learning regarding intimate partner violence perpetration. Victims & Offenders. 2023; 18(2):279-97. [DOI:10.1080/15564886.2021.1997845]

- Capaldi DM, Knoble NB, Shortt JW, Kim HK. A systematic review of risk factors for intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse. 2012; 3(2):231-80. [DOI:10.1891/1946-6560.3.2.231] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Raeisi S, Boostan D. [Violence against Balouch women (Persian)]. Quarterly Journal of Woman & Society. 2021; 12(46):46-65. [DOI:10.30495/jzvj.2021.22767.3014]

- Raisi SA. [Violence against women and intervening factors: A case study of Shahre Kord (Persian)]. Woman in Development and Politics. 2002; 1(3):45-66. [Link]

- Mirhashemi M, Sabori S. [Prediction of violence dimentions upon coping strategies in women of domestic violence victim (Persian)]. Family Pathology Counseling and Enrichment Journal. 2015; 1(2):1-13. [Link]

Type of Study: Original Article |

Subject:

Health Education

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |