Volume 12, Issue 2 (Spring 2024)

Iran J Health Sci 2024, 12(2): 79-88 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Sharifi S, Rostami F, Khorzoughi K B, Rahmati M. Palliative Care Models for Dementia in Nursing Homes: A Systematic Review. Iran J Health Sci 2024; 12 (2) :79-88

URL: http://jhs.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-915-en.html

URL: http://jhs.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-915-en.html

Department of Geriatric and Psychiatric Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran. , sharefesina8@gmail.com

Full-Text [PDF 843 kb]

(978 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (3082 Views)

Full-Text: (1078 Views)

Introduction

Dementia stands as a formidable challenge in the background of healthcare, particularly within the aging population [1]. With the aging of societies worldwide, the incidence and prevalence of dementia have witnessed a concerning upsurge [2]. According to a 2023 World Health Organization (WHO) report, 55 million people globally live with dementia, a number projected to increase substantially in the coming decades [3]. Understanding and addressing dementia is crucial for promoting successful aging and ensuring the well-being of older adults worldwide [4].

Nursing homes are pivotal in providing care and support to individuals with advanced dementia [5]. These facilities offer an environment tailored to individuals’ unique needs, requiring specialized attention, constant supervision, and comprehensive care [6]. Nursing homes serve as living spaces and therapeutic settings where trained professionals can deliver person-centered care, promote social engagement, and address the complex physical and emotional challenges that accompany dementia [5].

Palliative care represents a paradigm shift in healthcare, prioritizing quality of life (QoL) and holistic well-being for individuals facing severe illnesses, including dementia [7]. Rooted in a multidisciplinary approach, palliative care encompasses symptom management, psychosocial support, communication enhancement, and comprehensive care coordination [8]. The overarching goal is to alleviate suffering, enhance comfort, and empower individuals and their families to make informed decisions about care options [9].

For individuals with dementia, palliative care assumes a particularly vital role, as the disease’s progressive nature brings about unique challenges that extend beyond physical symptoms [10]. Cognitive decline, emotional distress, and communication difficulties can exacerbate the experience of both the individual and their caregivers. Palliative care in dementia focuses on addressing these complexities, tailoring interventions to preserve dignity, manage symptoms, foster emotional connection, and enhance the overall QoL [11].

Palliative care’s significance within nursing homes lies in its capacity to provide a comprehensive and compassionate framework for addressing the intricate needs of residents with advanced dementia [12, 13]. With their structured and supportive environment, nursing homes offer an ideal setting for implementing palliative care principles [14]. By integrating palliative care, these institutions can ensure that residents receive care that aligns with their preferences, values, and goals, fostering a sense of comfort and security [15].

The provision of palliative care within nursing homes for individuals with dementia presents a constellation of complex challenges that demand careful consideration. As dementia progresses, cognitive decline and communication impairments often hinder the effective assessment and management of pain and other distressing symptoms, leading to under-recognition and undertreatment of discomfort [16, 17]. Furthermore, the dynamic and fluctuating nature of dementia symptoms complicates care planning and necessitates an adaptable approach to symptom management [18]. Difficulties in accurately gauging residents’ preferences and goals of care, coupled with ethical dilemmas surrounding end-of-life decision-making, further accentuate the intricacies of delivering person-centered palliative care [12, 19].

This study aims to fill a critical need by conducting a systematic review of palliative care models in nursing homes specifically tailored for individuals with dementia. Recognizing the significant importance of this endeavor, our review seeks to identify and evaluate various applied models, assess their successes and challenges, and provide a comprehensive synthesis of the findings. By synthesizing existing research, we aim to offer crucial guidance to clinicians, policymakers, and researchers, thereby facilitating informed decisions that optimize palliative care provision in nursing homes. Ultimately, the main objective is to enhance the QoL for people with dementia by identifying effective palliative care models.

Materials and Methods

Our search for this systematic review was conducted without a specified time limit. We utilized four databases (PubMed, ScienceDirect, Web of Science, and Scopus) and the scientific search engine Google Scholar. We employed keywords such as “palliative care”, “palliative”, “dementia”, and “nursing home” to retrieve relevant articles. To expand the search results, we set no restrictions on the publication year of the articles. Subsequently, we imported the results into Endnote (an information management program). Finally, the reference lists of the identified articles were reviewed to identify pertinent literature.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were studies focusing on individuals with dementia residing in nursing homes, using palliative care models or interventions specifically designed for individuals with dementia in nursing homes, studies with full access to the entire text, with experimental (e.g. randomized controlled trials) and non-experimental study designs (e.g. observational studies, qualitative research), studies reporting outcomes related to the characteristics or efficacy of palliative care models for dementia in nursing homes, such as QoL, symptom management, caregiver burden, or healthcare resource utilization, and finally studies in English.

Exclusion criteria

We rejected review studies, studies on the implementation of a palliative care approach rather than those that specifically describe or evaluate a comprehensive palliative care model, duplicate studies, and non-English studies.

Study selection

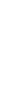

The study’s selection process followed the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. At first, duplicate studies were excluded. Then, the remaining articles were screened based on their Titles and Abstracts to meet the inclusion criteria. Afterward, the main texts of selected articles underwent a thorough review. To ensure consistent results, two researchers independently performed all selection process and extraction stages. When there was disagreement between researchers, a third reviewer was consulted as an arbitrator.

The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) checklist was employed to evaluate and determine the quality of articles based on observational studies. This checklist monitors 6 parts of “title”, “abstract”, “introduction”, “methods”, “results”, and “discussion” with 32 items and assesses various aspects of the study methodology. These elements cover the problem statement, objectives, study type, statistical population under investigation, sampling method and size determination, the definition of variables and procedures used for data collection, and analysis methods to derive statistical findings. Articles with a score of 16 or higher on the STROBE checklist earn medium to high methodological quality. On the other hand, articles with scores below 16 are regarded as having low methodological quality and thus excluded from further consideration.

Concurrently, the consolidated standards of reporting trials (CONSORT) tool was used for trial studies. The tool has a structured framework to evaluate the reporting quality of randomized controlled trials. We systematically evaluated the rigor and transparency of the trial studies by examining various components of the CONSORT checklist. These components include trial design, participant recruitment, interventions, outcome assessments, statistical analyses, and results presentation.

Data extraction

Two authors conducted the data extraction process using a pre-determined checklist, which included criteria such as the primary author’s identity, publication year, study site, sample size, palliative model, outcome measures, and summary of notable findings. Due to substantial heterogeneity observed in the palliative models, outcome measures employed, and analytical methodologies applied across studies reviewed, conducting a meta-analysis was deemed inappropriate for drawing significant conclusions. This decision aligns with the guidelines outlined in section 9 of the Cochrane handbook [20].

Results

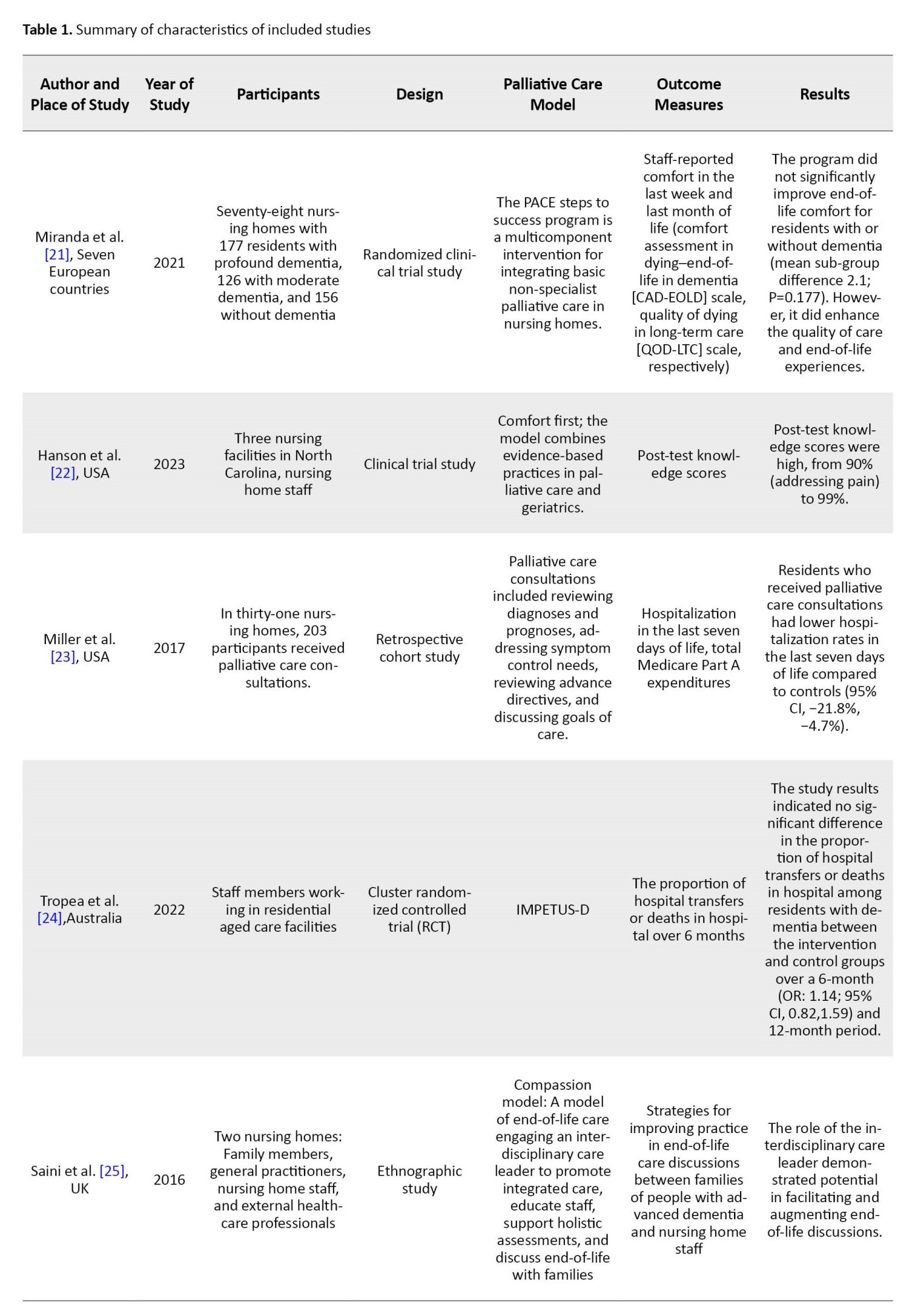

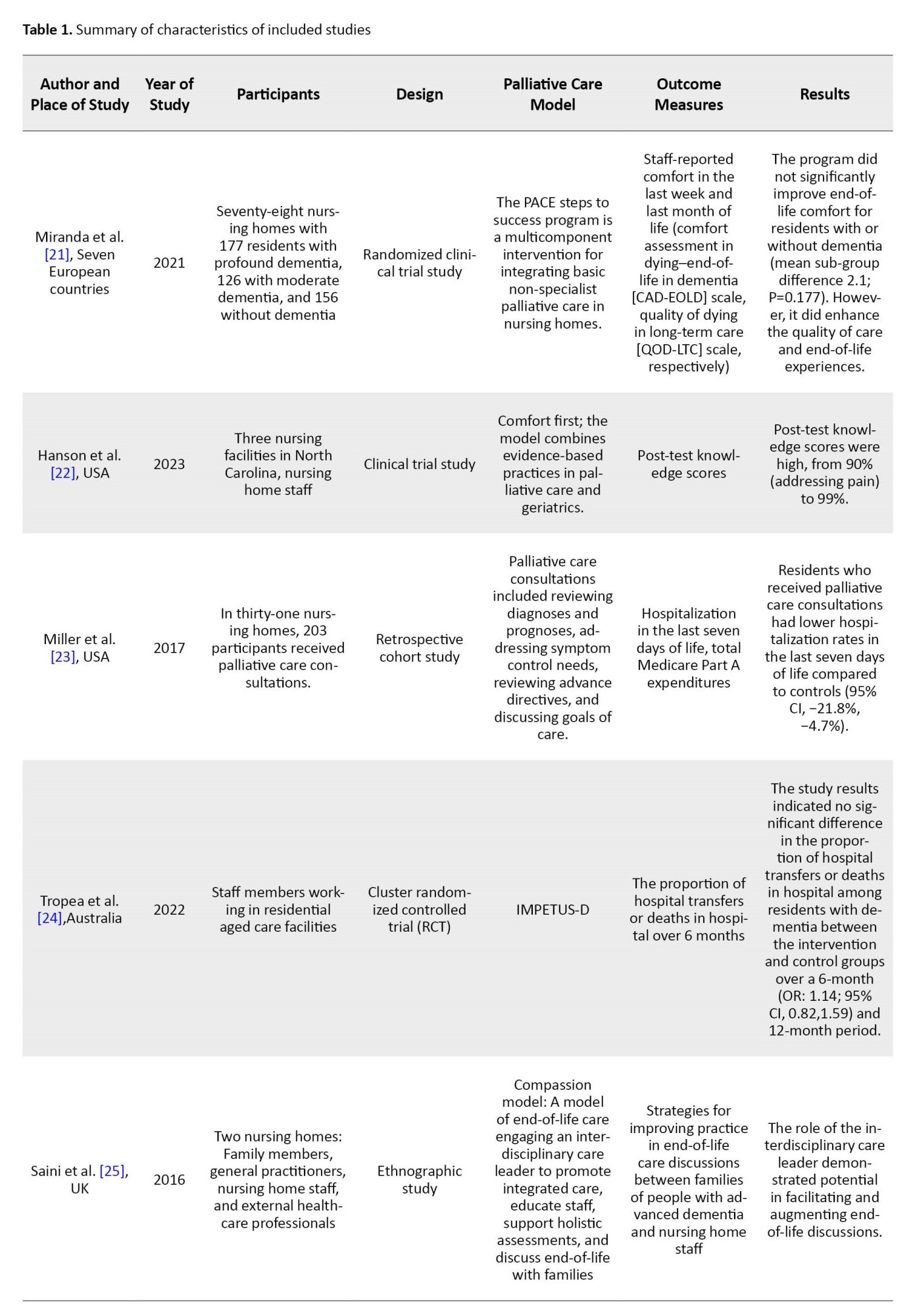

A total of 1880 articles were initially identified and managed using Endnote software. Then, 842 duplicates were excluded during the selection stage. Next, the “titles” and “abstracts” of the remaining articles were checked against the inclusion and exclusion criteria, excluding 992 articles. During the full review stage, 46 studies were evaluated, with 40 additional articles eliminated based on inclusion/exclusion criteria. One study was not written in English and thus excluded. Ultimately, 5 eligible articles remained for final evaluation (Figure 1), and their detailed information is presented in Table 1.

The PACE steps to success program

In a recent study by Miranda et al. (2021) [21], the effectiveness of implementing the palliative care for older people in Europe (PACE) steps to success program in nursing homes for individuals with dementia was examined concerning its impact on the quality of care and end-of-life experiences during the final month of life. The findings revealed that this multi-component program, which utilizes a train-the-trainer approach encompassing six steps, enhanced the overall quality of care provided (mean difference=2.7, 95% CI=−0.4, 5.9). However, it is essential to note that no statistically significant evidence was found indicating an improvement in comfort among residents at end-of-life stages, regardless of whether or not they had dementia. The PACE steps to success program integrates general and non-disease-specific palliative care into nursing home settings. It trains staff members to render high-quality palliative care throughout all stages, from advanced care planning and comprehensive support to pre-death phases.

The PACE steps to success program was developed to enhance the quality of care and end-of-life experience for residents in nursing homes. The program encompassed six sequential steps:

Advance care planning involving active engagement with both residents and their families,

Thorough assessment, comprehensive care planning, and periodic resident needs and challenges evaluation,

Facilitation of coordinated care through regular interdisciplinary palliative care review meetings on a monthly basis,

Provision of high-quality palliative care services that prioritize effective management of pain and depression symptoms,

Implementation of specialized care during the final days leading up to an individual’s passing and, delivery of post-death support and bereavement services.

Within this framework, the program specifically incorporated three elements tailored towards individuals affected by dementia, including training in communication strategies for advanced stages of dementia. It targeted approaches for symptom control in both dementia-afflicted and non-dementia-afflicted residents alike [26].

Comfort first

Hanson et al. (2023) executed a comfort-focused model in nursing homes and significantly improved post-test knowledge scores across multiple domains. Their findings showed notably high average scores, ranging from 90% in the domain of “addressing pain” to 99% in both “promoting QoL and comfort” and “making comfort first a reality” [22].

The comfort first training program promotes integrating palliative care and geriatric care principles employed in comfort matters dementia care. Its primary objective is to optimize comfort and boost the quality of care provided to individuals diagnosed with Alzheimer disease and related dementias (ADRD) within nursing home settings.

The program consists of a web-based training toolkit with six video modules that cover various topics related to dementia care, such as understanding the person with dementia, promoting QoL and comfort, working as a team in comfort-focused care, responding to distress in people with dementia, addressing pain in individuals with dementia, and making comfort first a reality in person-directed care plans. These modules feature professional narration, onscreen text graphics, and video demonstrations of best practices. The program provides an implementation manual with detailed instructions on implementing and sustaining the comfort first program. It includes guidance on engaging administrative and clinical leaders, delivering training as in-service programs, and recommending procedures for performance improvement.

Palliative care consultations

In a study by Miller et al. in 2017, individuals who received counseling services related to palliative care exhibited a lower frequency of hospitalizations within the final seven days before their death [23]. These consultations, led by nurse practitioner palliative care specialists under the supervision of certified palliative care physicians, comprised a comprehensive assessment and support framework. They involved a thorough review of diagnoses and prognoses, assessment of symptom control, examination of advance directives, and facilitated discussions regarding goals of care. In addition, these consultations often included family meetings to ensure alignment and understanding of the care plan. The study’s main findings indicated a significant reduction in hospitalizations during the final days of life among individuals who received these specialized palliative care consultations, underscoring the importance of proactive and multidisciplinary approaches in end-of-life care.

Improving palliative care education and training using simulation in dementia (IMPETUS-D)

According to the Tropea et al. study (2022), the findings indicate that the IMPETUS-D training program does not demonstrate any significant impact on hospital transfer rates or mortality outcomes among residents diagnosed with dementia over the 6- and 12-month periods [24].

The primary objective of the IMPETUS-D program is to enhance the quality of palliative care delivery and improve outcomes for individuals with dementia residing in nursing homes. This comprehensive program comprises 11 modules that encompass essential elements of optimal palliative and end-of-life care for this population. These modules incorporate case studies and concise video scenarios filmed within genuine care home environments, facilitating practical application and contextual understanding.

Compassion model

Saini et al. study (2016) findings demonstrate the influential role of the compassion model in promoting and facilitating discussions pertaining to end-of-life care [25].

The compassion intervention, developed as part of a research program on end-of-life care in advanced dementia, consists of two core components. Firstly, it focuses on facilitating integrated care for individuals with advanced dementia. This issue involves promoting engagement with healthcare professionals from various disciplines to address the diverse needs of residents. The intervention identifies barriers nursing home residents face in accessing healthcare services. It employs an integrated care leader (ICL) who conducts holistic assessments, collaborates with nursing home nurses and general practitioners, attends multidisciplinary team meetings, and discusses with family members to ensure comprehensive care planning.

Secondly, the intervention provides training and support for families and caregivers caring for individuals with advanced dementia. The ICL conducts formal training sessions for staff members covering topics such as behavioral symptoms management, pain management, and end-of-life care. Family sessions focus on enhancing their understanding of dementia progression, common end-of-life symptoms experienced by individuals with dementia, and sharing personal experiences related to caregiving. In addition to formal training sessions, ICL provides informal on-the-job advice and support [27].

Discussion

This systematic review examined different palliative care models for individuals with dementia in nursing homes. Another objective was to probe the characteristics and efficacy of models. The review identified five distinct models: The compassion model, IMPETUS-D, palliative care consultations, comfort first, and the PACE steps to success program. These models have been specifically designed to address the unique needs of people with dementia residing in nursing homes.

The efficacy of these palliative care models varies based on their objectives and approaches. For example, the PACE steps to success program enhances the overall quality of care for individuals with dementia in nursing homes [21]. Similarly, the comfort first model significantly improves post-test knowledge scores across multiple domains [22]. However, the IMPETUS-D training program has no significant impact on hospital transfer rates or mortality outcomes among residents with dementia [24]. Also, the compassion intervention model highlighted the significance of an integrated care approach for individuals with advanced dementia [25].

Dementia care principles are vital in providing optimal care for individuals with dementia residing in nursing homes. Person-centered care is a fundamental approach, focusing on tailoring the environment and interventions to meet individuals’ unique needs and preferences [28]. This issue includes promoting autonomy, maintaining dignity, and fostering meaningful social engagement [29]. In addition, staff training programs that emphasize a person-centered approach and equip caregivers with the necessary knowledge and skills are essential for delivering quality dementia care within nursing home settings [30]. Notably, the principles of person-centered care are seen across all models under discussion. Each model uniquely strives to align with these principles by enhancing personalized care, minimizing distress, and maintaining a dignified and engaging care environment.

The nursing home environment presents a multifaceted context characterized by intricate contextual barriers outlined in prior research, including prominent factors like high staff turnover and heavy workloads [31]. These barriers encompass diverse aspects, ranging from staff-oriented concerns such as turnover and workload to organizational dynamics like time limitations and communication gaps [32]. Moreover, the intricate and voluntary nature of the training intervention contributes to further challenges. These complex hurdles are notably evident within palliative care models that rely on training nursing home staff, exemplified by initiatives like IMPETUS-D and comfort first.

In this context, the insufficiency of specialized palliative care services becomes a notable challenge in nursing homes. The limited availability of palliative care experts within healthcare systems hampers consistent consultation access, partly due to staffing constraints and geographical limitations [33]. This challenge is particularly relevant in models centered around consultation-based palliative care interventions.

Similarly, within the scope of the comfort first model, engaging family members and caregivers in the process proves to be challenging due to various factors such as logistical constraints, differing expectations, or emotional distress [34]. Moreover, fostering robust social support networks for family caregivers of Alzheimer patients is essential [35], as it can mitigate the multifaceted challenges encountered in implementing palliative care initiatives within nursing home settings, where diverse obstacles, both internal and external, influence the effectiveness of models designed to enhance care provision for individuals with dementia.

One notable limitation of this systematic review is its restriction to English-language articles. By exclusively focusing on literature written in English, the review may have overlooked valuable contributions and perspectives from non-English sources, potentially limiting the inclusivity and diversity of the findings. However, despite this limitation, the systematic review offers a significant foundation for comprehending the landscape of palliative care models tailored to individuals with dementia residing in nursing homes.

In summation, this systematic review has provided valuable insights into palliative care models in dementia care in nursing homes. It emphasizes the significance of person-centered principles, explores the nuances of integration, and underscores the multifaceted challenges inherent in delivering comprehensive care to this vulnerable population. Looking ahead, our study calls for future research to explore innovative approaches, evaluate long-term outcomes, and embark on cross-cultural comparisons. These findings offer practical implications for healthcare practitioners seeking to implement effective palliative care models, fostering a holistic and dignified care journey for individuals with dementia in nursing homes.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this systematic review has shed light on the landscape of palliative care models for individuals with dementia residing in nursing homes. Through the comprehensive examination of 5 distinct models (compassion, IMPETUS-D, palliative care consultations, comfort first, and the PACE steps to success program), this study explored the successes and challenges inherent in enhancing care quality for this vulnerable population. The review underscores the significance of person-centered care principles as a guiding force within these models, emphasizing the tailored, dignified, and holistic approach they collectively advocate. However, it is noteworthy that the compassion model and palliative care consultations demonstrate comparatively better outcomes in terms of effectiveness. Nonetheless, these models’ varying degrees of effectiveness reflect the complex interplay between their objectives, strategies, and the intricate nursing home environment.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This article is a meta-analysis with no human or animal sample.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization and supervision: Sina Sharifi and Mahmoud Rahmati; Methodology: Sina Sharifi and Fatemeh Rostami; Data collection: Kimia Babaei Khorzoughi; Data analysis: Sina Sharifi and Fatemeh Rostami; Funding acquisition and resources: Mahmoud Rahmati; Investigation and writing: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Student Research Committee of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences for its assistance in supporting this research.

References

Dementia stands as a formidable challenge in the background of healthcare, particularly within the aging population [1]. With the aging of societies worldwide, the incidence and prevalence of dementia have witnessed a concerning upsurge [2]. According to a 2023 World Health Organization (WHO) report, 55 million people globally live with dementia, a number projected to increase substantially in the coming decades [3]. Understanding and addressing dementia is crucial for promoting successful aging and ensuring the well-being of older adults worldwide [4].

Nursing homes are pivotal in providing care and support to individuals with advanced dementia [5]. These facilities offer an environment tailored to individuals’ unique needs, requiring specialized attention, constant supervision, and comprehensive care [6]. Nursing homes serve as living spaces and therapeutic settings where trained professionals can deliver person-centered care, promote social engagement, and address the complex physical and emotional challenges that accompany dementia [5].

Palliative care represents a paradigm shift in healthcare, prioritizing quality of life (QoL) and holistic well-being for individuals facing severe illnesses, including dementia [7]. Rooted in a multidisciplinary approach, palliative care encompasses symptom management, psychosocial support, communication enhancement, and comprehensive care coordination [8]. The overarching goal is to alleviate suffering, enhance comfort, and empower individuals and their families to make informed decisions about care options [9].

For individuals with dementia, palliative care assumes a particularly vital role, as the disease’s progressive nature brings about unique challenges that extend beyond physical symptoms [10]. Cognitive decline, emotional distress, and communication difficulties can exacerbate the experience of both the individual and their caregivers. Palliative care in dementia focuses on addressing these complexities, tailoring interventions to preserve dignity, manage symptoms, foster emotional connection, and enhance the overall QoL [11].

Palliative care’s significance within nursing homes lies in its capacity to provide a comprehensive and compassionate framework for addressing the intricate needs of residents with advanced dementia [12, 13]. With their structured and supportive environment, nursing homes offer an ideal setting for implementing palliative care principles [14]. By integrating palliative care, these institutions can ensure that residents receive care that aligns with their preferences, values, and goals, fostering a sense of comfort and security [15].

The provision of palliative care within nursing homes for individuals with dementia presents a constellation of complex challenges that demand careful consideration. As dementia progresses, cognitive decline and communication impairments often hinder the effective assessment and management of pain and other distressing symptoms, leading to under-recognition and undertreatment of discomfort [16, 17]. Furthermore, the dynamic and fluctuating nature of dementia symptoms complicates care planning and necessitates an adaptable approach to symptom management [18]. Difficulties in accurately gauging residents’ preferences and goals of care, coupled with ethical dilemmas surrounding end-of-life decision-making, further accentuate the intricacies of delivering person-centered palliative care [12, 19].

This study aims to fill a critical need by conducting a systematic review of palliative care models in nursing homes specifically tailored for individuals with dementia. Recognizing the significant importance of this endeavor, our review seeks to identify and evaluate various applied models, assess their successes and challenges, and provide a comprehensive synthesis of the findings. By synthesizing existing research, we aim to offer crucial guidance to clinicians, policymakers, and researchers, thereby facilitating informed decisions that optimize palliative care provision in nursing homes. Ultimately, the main objective is to enhance the QoL for people with dementia by identifying effective palliative care models.

Materials and Methods

Our search for this systematic review was conducted without a specified time limit. We utilized four databases (PubMed, ScienceDirect, Web of Science, and Scopus) and the scientific search engine Google Scholar. We employed keywords such as “palliative care”, “palliative”, “dementia”, and “nursing home” to retrieve relevant articles. To expand the search results, we set no restrictions on the publication year of the articles. Subsequently, we imported the results into Endnote (an information management program). Finally, the reference lists of the identified articles were reviewed to identify pertinent literature.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were studies focusing on individuals with dementia residing in nursing homes, using palliative care models or interventions specifically designed for individuals with dementia in nursing homes, studies with full access to the entire text, with experimental (e.g. randomized controlled trials) and non-experimental study designs (e.g. observational studies, qualitative research), studies reporting outcomes related to the characteristics or efficacy of palliative care models for dementia in nursing homes, such as QoL, symptom management, caregiver burden, or healthcare resource utilization, and finally studies in English.

Exclusion criteria

We rejected review studies, studies on the implementation of a palliative care approach rather than those that specifically describe or evaluate a comprehensive palliative care model, duplicate studies, and non-English studies.

Study selection

The study’s selection process followed the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. At first, duplicate studies were excluded. Then, the remaining articles were screened based on their Titles and Abstracts to meet the inclusion criteria. Afterward, the main texts of selected articles underwent a thorough review. To ensure consistent results, two researchers independently performed all selection process and extraction stages. When there was disagreement between researchers, a third reviewer was consulted as an arbitrator.

The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) checklist was employed to evaluate and determine the quality of articles based on observational studies. This checklist monitors 6 parts of “title”, “abstract”, “introduction”, “methods”, “results”, and “discussion” with 32 items and assesses various aspects of the study methodology. These elements cover the problem statement, objectives, study type, statistical population under investigation, sampling method and size determination, the definition of variables and procedures used for data collection, and analysis methods to derive statistical findings. Articles with a score of 16 or higher on the STROBE checklist earn medium to high methodological quality. On the other hand, articles with scores below 16 are regarded as having low methodological quality and thus excluded from further consideration.

Concurrently, the consolidated standards of reporting trials (CONSORT) tool was used for trial studies. The tool has a structured framework to evaluate the reporting quality of randomized controlled trials. We systematically evaluated the rigor and transparency of the trial studies by examining various components of the CONSORT checklist. These components include trial design, participant recruitment, interventions, outcome assessments, statistical analyses, and results presentation.

Data extraction

Two authors conducted the data extraction process using a pre-determined checklist, which included criteria such as the primary author’s identity, publication year, study site, sample size, palliative model, outcome measures, and summary of notable findings. Due to substantial heterogeneity observed in the palliative models, outcome measures employed, and analytical methodologies applied across studies reviewed, conducting a meta-analysis was deemed inappropriate for drawing significant conclusions. This decision aligns with the guidelines outlined in section 9 of the Cochrane handbook [20].

Results

A total of 1880 articles were initially identified and managed using Endnote software. Then, 842 duplicates were excluded during the selection stage. Next, the “titles” and “abstracts” of the remaining articles were checked against the inclusion and exclusion criteria, excluding 992 articles. During the full review stage, 46 studies were evaluated, with 40 additional articles eliminated based on inclusion/exclusion criteria. One study was not written in English and thus excluded. Ultimately, 5 eligible articles remained for final evaluation (Figure 1), and their detailed information is presented in Table 1.

The PACE steps to success program

In a recent study by Miranda et al. (2021) [21], the effectiveness of implementing the palliative care for older people in Europe (PACE) steps to success program in nursing homes for individuals with dementia was examined concerning its impact on the quality of care and end-of-life experiences during the final month of life. The findings revealed that this multi-component program, which utilizes a train-the-trainer approach encompassing six steps, enhanced the overall quality of care provided (mean difference=2.7, 95% CI=−0.4, 5.9). However, it is essential to note that no statistically significant evidence was found indicating an improvement in comfort among residents at end-of-life stages, regardless of whether or not they had dementia. The PACE steps to success program integrates general and non-disease-specific palliative care into nursing home settings. It trains staff members to render high-quality palliative care throughout all stages, from advanced care planning and comprehensive support to pre-death phases.

The PACE steps to success program was developed to enhance the quality of care and end-of-life experience for residents in nursing homes. The program encompassed six sequential steps:

Advance care planning involving active engagement with both residents and their families,

Thorough assessment, comprehensive care planning, and periodic resident needs and challenges evaluation,

Facilitation of coordinated care through regular interdisciplinary palliative care review meetings on a monthly basis,

Provision of high-quality palliative care services that prioritize effective management of pain and depression symptoms,

Implementation of specialized care during the final days leading up to an individual’s passing and, delivery of post-death support and bereavement services.

Within this framework, the program specifically incorporated three elements tailored towards individuals affected by dementia, including training in communication strategies for advanced stages of dementia. It targeted approaches for symptom control in both dementia-afflicted and non-dementia-afflicted residents alike [26].

Comfort first

Hanson et al. (2023) executed a comfort-focused model in nursing homes and significantly improved post-test knowledge scores across multiple domains. Their findings showed notably high average scores, ranging from 90% in the domain of “addressing pain” to 99% in both “promoting QoL and comfort” and “making comfort first a reality” [22].

The comfort first training program promotes integrating palliative care and geriatric care principles employed in comfort matters dementia care. Its primary objective is to optimize comfort and boost the quality of care provided to individuals diagnosed with Alzheimer disease and related dementias (ADRD) within nursing home settings.

The program consists of a web-based training toolkit with six video modules that cover various topics related to dementia care, such as understanding the person with dementia, promoting QoL and comfort, working as a team in comfort-focused care, responding to distress in people with dementia, addressing pain in individuals with dementia, and making comfort first a reality in person-directed care plans. These modules feature professional narration, onscreen text graphics, and video demonstrations of best practices. The program provides an implementation manual with detailed instructions on implementing and sustaining the comfort first program. It includes guidance on engaging administrative and clinical leaders, delivering training as in-service programs, and recommending procedures for performance improvement.

Palliative care consultations

In a study by Miller et al. in 2017, individuals who received counseling services related to palliative care exhibited a lower frequency of hospitalizations within the final seven days before their death [23]. These consultations, led by nurse practitioner palliative care specialists under the supervision of certified palliative care physicians, comprised a comprehensive assessment and support framework. They involved a thorough review of diagnoses and prognoses, assessment of symptom control, examination of advance directives, and facilitated discussions regarding goals of care. In addition, these consultations often included family meetings to ensure alignment and understanding of the care plan. The study’s main findings indicated a significant reduction in hospitalizations during the final days of life among individuals who received these specialized palliative care consultations, underscoring the importance of proactive and multidisciplinary approaches in end-of-life care.

Improving palliative care education and training using simulation in dementia (IMPETUS-D)

According to the Tropea et al. study (2022), the findings indicate that the IMPETUS-D training program does not demonstrate any significant impact on hospital transfer rates or mortality outcomes among residents diagnosed with dementia over the 6- and 12-month periods [24].

The primary objective of the IMPETUS-D program is to enhance the quality of palliative care delivery and improve outcomes for individuals with dementia residing in nursing homes. This comprehensive program comprises 11 modules that encompass essential elements of optimal palliative and end-of-life care for this population. These modules incorporate case studies and concise video scenarios filmed within genuine care home environments, facilitating practical application and contextual understanding.

Compassion model

Saini et al. study (2016) findings demonstrate the influential role of the compassion model in promoting and facilitating discussions pertaining to end-of-life care [25].

The compassion intervention, developed as part of a research program on end-of-life care in advanced dementia, consists of two core components. Firstly, it focuses on facilitating integrated care for individuals with advanced dementia. This issue involves promoting engagement with healthcare professionals from various disciplines to address the diverse needs of residents. The intervention identifies barriers nursing home residents face in accessing healthcare services. It employs an integrated care leader (ICL) who conducts holistic assessments, collaborates with nursing home nurses and general practitioners, attends multidisciplinary team meetings, and discusses with family members to ensure comprehensive care planning.

Secondly, the intervention provides training and support for families and caregivers caring for individuals with advanced dementia. The ICL conducts formal training sessions for staff members covering topics such as behavioral symptoms management, pain management, and end-of-life care. Family sessions focus on enhancing their understanding of dementia progression, common end-of-life symptoms experienced by individuals with dementia, and sharing personal experiences related to caregiving. In addition to formal training sessions, ICL provides informal on-the-job advice and support [27].

Discussion

This systematic review examined different palliative care models for individuals with dementia in nursing homes. Another objective was to probe the characteristics and efficacy of models. The review identified five distinct models: The compassion model, IMPETUS-D, palliative care consultations, comfort first, and the PACE steps to success program. These models have been specifically designed to address the unique needs of people with dementia residing in nursing homes.

The efficacy of these palliative care models varies based on their objectives and approaches. For example, the PACE steps to success program enhances the overall quality of care for individuals with dementia in nursing homes [21]. Similarly, the comfort first model significantly improves post-test knowledge scores across multiple domains [22]. However, the IMPETUS-D training program has no significant impact on hospital transfer rates or mortality outcomes among residents with dementia [24]. Also, the compassion intervention model highlighted the significance of an integrated care approach for individuals with advanced dementia [25].

Dementia care principles are vital in providing optimal care for individuals with dementia residing in nursing homes. Person-centered care is a fundamental approach, focusing on tailoring the environment and interventions to meet individuals’ unique needs and preferences [28]. This issue includes promoting autonomy, maintaining dignity, and fostering meaningful social engagement [29]. In addition, staff training programs that emphasize a person-centered approach and equip caregivers with the necessary knowledge and skills are essential for delivering quality dementia care within nursing home settings [30]. Notably, the principles of person-centered care are seen across all models under discussion. Each model uniquely strives to align with these principles by enhancing personalized care, minimizing distress, and maintaining a dignified and engaging care environment.

The nursing home environment presents a multifaceted context characterized by intricate contextual barriers outlined in prior research, including prominent factors like high staff turnover and heavy workloads [31]. These barriers encompass diverse aspects, ranging from staff-oriented concerns such as turnover and workload to organizational dynamics like time limitations and communication gaps [32]. Moreover, the intricate and voluntary nature of the training intervention contributes to further challenges. These complex hurdles are notably evident within palliative care models that rely on training nursing home staff, exemplified by initiatives like IMPETUS-D and comfort first.

In this context, the insufficiency of specialized palliative care services becomes a notable challenge in nursing homes. The limited availability of palliative care experts within healthcare systems hampers consistent consultation access, partly due to staffing constraints and geographical limitations [33]. This challenge is particularly relevant in models centered around consultation-based palliative care interventions.

Similarly, within the scope of the comfort first model, engaging family members and caregivers in the process proves to be challenging due to various factors such as logistical constraints, differing expectations, or emotional distress [34]. Moreover, fostering robust social support networks for family caregivers of Alzheimer patients is essential [35], as it can mitigate the multifaceted challenges encountered in implementing palliative care initiatives within nursing home settings, where diverse obstacles, both internal and external, influence the effectiveness of models designed to enhance care provision for individuals with dementia.

One notable limitation of this systematic review is its restriction to English-language articles. By exclusively focusing on literature written in English, the review may have overlooked valuable contributions and perspectives from non-English sources, potentially limiting the inclusivity and diversity of the findings. However, despite this limitation, the systematic review offers a significant foundation for comprehending the landscape of palliative care models tailored to individuals with dementia residing in nursing homes.

In summation, this systematic review has provided valuable insights into palliative care models in dementia care in nursing homes. It emphasizes the significance of person-centered principles, explores the nuances of integration, and underscores the multifaceted challenges inherent in delivering comprehensive care to this vulnerable population. Looking ahead, our study calls for future research to explore innovative approaches, evaluate long-term outcomes, and embark on cross-cultural comparisons. These findings offer practical implications for healthcare practitioners seeking to implement effective palliative care models, fostering a holistic and dignified care journey for individuals with dementia in nursing homes.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this systematic review has shed light on the landscape of palliative care models for individuals with dementia residing in nursing homes. Through the comprehensive examination of 5 distinct models (compassion, IMPETUS-D, palliative care consultations, comfort first, and the PACE steps to success program), this study explored the successes and challenges inherent in enhancing care quality for this vulnerable population. The review underscores the significance of person-centered care principles as a guiding force within these models, emphasizing the tailored, dignified, and holistic approach they collectively advocate. However, it is noteworthy that the compassion model and palliative care consultations demonstrate comparatively better outcomes in terms of effectiveness. Nonetheless, these models’ varying degrees of effectiveness reflect the complex interplay between their objectives, strategies, and the intricate nursing home environment.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This article is a meta-analysis with no human or animal sample.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization and supervision: Sina Sharifi and Mahmoud Rahmati; Methodology: Sina Sharifi and Fatemeh Rostami; Data collection: Kimia Babaei Khorzoughi; Data analysis: Sina Sharifi and Fatemeh Rostami; Funding acquisition and resources: Mahmoud Rahmati; Investigation and writing: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Student Research Committee of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences for its assistance in supporting this research.

References

- Prince M, Bryce R, Albanese E, Wimo A, Ribeiro W, Ferri CP. The global prevalence of dementia: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Alzheimer's & Dementia. 2013; 9(1):63-75.e2. [DOI:10.1016/j.jalz.2012.11.007] [PMID]

- Cao Q, Tan CC, Xu W, Hu H, Cao XP, Dong Q, et al. The prevalence of dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 2020; 73(3):1157-66. [DOI:10.3233/JAD-191092] [PMID]

- WHO. Dementia. Geneva: WHO;2023. [Link]

- Irwin K, Sexton C, Daniel T, Lawlor B, Naci L. Healthy aging and dementia: Two roads diverging in midlife? Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience. 2018; 10:275. [DOI:10.3389/fnagi.2018.00275] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Gaugler JE, Yu F, Davila HW, Shippee T. Alzheimer’s disease and nursing homes. Health Affairs (Project Hope). 2014; 33(4):650-7. [DOI:10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1268] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Sanford AM, Orrell M, Tolson D, Abbatecola AM, Arai H, Bauer JM, et al. An international definition for “nursing home”. Journal of The American Medical Directors Association. 2015; 16(3):181-4. [DOI:10.1016/j.jamda.2014.12.013] [PMID]

- Stewart JT, Schultz SK. Palliative care for dementia. Psychiatric Clinics. 2018; 41(1):141-51. [DOI:10.1016/j.psc.2017.10.011] [PMID]

- Ryan S, Wong J, Chow R, Zimmermann C. Evolving definitions of palliative care: Upstream migration or confusion? Current Treatment Options in Oncology. 2020; 21(3):20. [DOI:10.1007/s11864-020-0716-4] [PMID]

- Rome RB, Luminais HH, Bourgeois DA, Blais CM. The role of palliative care at the end of life. Ochsner Journal. 2011; 11(4):348-52. [PMID]

- Cerejeira J, Lagarto L, Mukaetova-Ladinska EB. Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Frontiers in Neurology. 2012; 3:73. [DOI:10.3389/fneur.2012.00073] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Eisenmann Y, Golla H, Schmidt H, Voltz R, Perrar KM. Palliative care in advanced dementia. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2020; 11:699. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00699] [PMID] [PMCID]

- van der Steen JT, Radbruch L, Hertogh CM, de Boer ME, Hughes JC, Larkin P, et al. White paper defining optimal palliative care in older people with dementia: A Delphi study and recommendations from the European Association for Palliative Care. Palliative Medicine. 2014; 28(3):197-209. [DOI:10.1177/0269216313493685] [PMID]

- Bolt SR, Meijers JMM, van der Steen JT, Schols JMGA, Zwakhalen SMG. Nursing staff needs in providing palliative care for persons with dementia at home or in nursing homes: A survey. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2020; 52(2):164-73. [DOI:10.1111/jnu.12542] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Carlson MD, Lim B, Meier DE. Strategies and innovative models for delivering palliative care in nursing homes. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2011; 12(2):91-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.jamda.2010.07.016] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Meier DE, Lim B, Carlson MD. Raising the standard: Palliative care in nursing homes. Health Affairs. 2010; 29(1):136-40. [DOI:10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0912] [PMID]

- Horgas AL, Elliott AF. Pain assessment and management in persons with dementia. The Nursing Clinics of North America. 2004; 39(3):593-606. [DOI:10.1016/j.cnur.2004.02.013] [PMID]

- Husebo BS, Ballard C, Aarsland D. Pain treatment of agitation in patients with dementia: A systematic review. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2011; 26(10):1012-8. [DOI:10.1002/gps.2649] [PMID]

- van der Steen JT, Lemos Dekker N, Gijsberts MHE, Vermeulen LH, Mahler MM, The BA. Palliative care for people with dementia in the terminal phase: A mixed-methods qualitative study to inform service development. BMC Palliative Care. 2017; 16(1):28. [DOI:10.1186/s12904-017-0201-4] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Goodman C, Froggatt K, Amador S, Mathie E, Mayrhofer A. End of life care interventions for people with dementia in care homes: Addressing uncertainty within a framework for service delivery and evaluation. BMC Palliative Care. 2015; 14:42. [DOI:10.1186/s12904-015-0040-0] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Higgins JP and Green s. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Hoboken: Wiley; 2008. [Link]

- Miranda R, Smets T, Van Den Noortgate N, van der Steen JT, Deliens L, Payne S, et al. No difference in effects of ‘PACE steps to success’ palliative care program for nursing home residents with and without dementia: A pre-planned subgroup analysis of the seven-country PACE trial. BMC Palliative Care. 2021; 20(1):39. [DOI:10.1186/s12904-021-00734-1] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Hanson LC, Meeks N, Guo J, Alonzo TRM, Mitchell KM, Gallagher M, et al. Comfort First: Development and pilot testing of a web-based video training to disseminate Comfort Matters dementia care. Journal Of The American Geriatrics Society. 2023; 71(8):2564-70. [DOI:10.1111/jgs.18346] [PMID]

- Miller SC, Lima JC, Intrator O, Martin E, Bull J, Hanson LC. Specialty palliative care consultations for nursing home residents with dementia. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2017; 54(1):9-16.e5. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.03.005] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Tropea J, Nestel D, Johnson C, Hayes BJ, Hutchinson AF, Brand C, et al. Evaluation of improving palliative care education and training using simulation in dementia (IMPETUS-D) a staff simulation training intervention to improve palliative care of people with advanced dementia living in nursing homes: A cluster randomised controlled trial. BMC Geriatrics. 2022; 22(1):127. [DOI:10.1186/s12877-022-02809-x] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Saini G, Sampson EL, Davis S, Kupeli N, Harrington J, Leavey G, et al. An ethnographic study of strategies to support discussions with family members on end-of-life care for people with advanced dementia in nursing homes. BMC Palliative Care. 2016; 15:55. [DOI:10.1186/s12904-016-0127-2] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Smets T, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BBD, Miranda R, Pivodic L, Tanghe M, van Hout H, et al. Integrating palliative care in long-term care facilities across Europe (PACE): Protocol of a cluster randomized controlled trial of the ‘PACE Steps to Success’ intervention in seven countries. BMC Palliative Care. 2018; 17(1):47. [DOI:10.1186/s12904-018-0297-1] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Elliott M, Harrington J, Moore K, Davis S, Kupeli N, Vickerstaff V, et al. A protocol for an exploratory phase I mixed-methods study of enhanced integrated care for care home residents with advanced dementia: The Compassion Intervention. BMJ open. 2014; 4(6):e005661. [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005661] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Fazio S, Pace D, Flinner J, Kallmyer B. The fundamentals of person-centered care for individuals with dementia. The Gerontologist. 2018; 58(suppl_1):S10-9. [DOI:10.1093/geront/gnx122] [PMID]

- Brooker D, Latham I. Person-centred dementia care: Making services better with the VIPS framework. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2015. [Link]

- Chenoweth L, Jeon YH, Stein-Parbury J, Forbes I, Fleming R, Cook J, et al. PerCEN trial participant perspectives on the implementation and outcomes of person-centered dementia care and environments. International Psychogeriatrics. 2015; 27(12):2045-57. [DOI:10.1017/S1041610215001350] [PMID]

- Low LF, Fletcher J, Goodenough B, Jeon YH, Etherton-Beer C, MacAndrew M, et al. A systematic review of interventions to change staff care practices in order to improve resident outcomes in nursing homes. Plos One. 2015; 10(11):e0140711. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0140711] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Park YH, Bang HL, Kim GH, Oh S, Jung YI, Kim H. Current status and barriers to health care services for nursing home residents: Perspectives of staffs in Korean nursing homes. Korean Journal of Adult Nursing. 2015; 27(4):418-27. [Link]

- Schenker Y, Arnold R. The next era of palliative care. JAMA. 2015; 314(15):1565-6. [DOI:10.1001/jama.2015.11217] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Alam S, Hannon B, Zimmermann C. Palliative care for family caregivers. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2020; 38(9):926-36. [DOI:10.1200/JCO.19.00018] [PMID]

- Dadashi-Tonkaboni N, Peyman N. Social support on family caregivers of alzheimer patients: A systematic review. Iranian Journal of Health Sciences. 2023; 11(3):157-64. [DOI:10.32598/ijhs.11.3.933.1]

Type of Study: Review Article |

Subject:

Geriatrics

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |