Volume 10, Issue 4 (Autumn 2022)

Iran J Health Sci 2022, 10(4): 1-10 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Mahdavinoor S M M, Mollaei A, Mahdavinoor S H. Meaning in Life of Medical Sciences Students During COVID-19 Outbreak: A Cross-sectional Study. Iran J Health Sci 2022; 10 (4) :1-10

URL: http://jhs.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-815-en.html

URL: http://jhs.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-815-en.html

Department of Islamic Theology, Yadegar-e-Imam Khomeini, Shahr-e Rey Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran. , hmahdavinoor@yahoo.com

Full-Text [PDF 1003 kb]

(898 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2249 Views)

Full-Text: (605 Views)

1. Introduction

In 2019, Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) turned into the greatest widespread infectious pneumonia in the world. Given the high prevalence of the disease, World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 pneumonia a pandemic. The virus quickly spread to all world countries and led to outbreaks in countries such as South Korea, Iran, and Italy [1, 2]. The disease affected many people worldwide and posed unique challenges in all aspects of life [3]. Restrictions imposed by the outbreak of COVID-19 affected people’s lifestyles and mental health status [4, 5]. Students were exposed to the psychological problems caused by this epidemic more than the general population due to their special status. Therefore, there is an urgent need to assess and monitor the unprecedented burden of mental health on students [6, 7, 8, 9]. The damage to students’ mental health can be prevented by addressing the underlying cause of the problem and implementing effective prevention programs [8].

The concept of “meaning in life” is directly related to mental health [10, 11, 12]. The meaning in life refers to the main purpose and concept of each person’s life. Many consider life’s meaning as the purpose of life [13, 14]. The meaning in life is the basic reason for human existence. Why does a human being not commit suicide despite all the hardships in life? Why do humans endure so much suffering? Why do people with incurable diseases such as cancer have to tolerate the adversities of the disease and its treatment? Is life worth all this suffering? The answer to these questions is related to the meaning of each person’s life. The reason for people’s existence is the meaning of their life; namely, the answer people give to the question of why they do not commit suicide.

The question of meaning in life arises when human beings are confronted with negative, bitter, painful, and gloomy aspects of their life. Is it natural for a person to think that life is worthwhile when faced with bitter moments of failure? Or what is it that makes life worth living [15]?

Usually, humans just try to enjoy life when they are not in a difficult situation. However, when the degree of suffering is greater than that of pleasure, a man asks whether it is worth living. Why should I not kill myself now that life’s suffering is more than its pleasure to free myself from pain and grief [16]? In this situation, humans seek a meaning that gives value to their life. The meaning in life is a vital psychological element for resilience to injury and disaster, which gives people the feeling that their life is important even in difficult times [17]. If people find such a meaning, they can endure suffering and sorrows, surviving the hardships and extremely difficult conditions of life [18]. However, if people fail to find meaning in their lives, they will undergo an existential vacuum. An existential vacuum is created in a person who has no meaning in life. This vacuity is a sensation of complete emptiness and lack of purpose to continue living. Therefore, suicide may seem appropriate to alleviate this distressing situation [19].

Meaning in life has two aspects [20]:

The Presence of meaning (POM) indicates whether people consider their lives important and purposeful. The term refers to understanding oneself and the world, including awareness of how to fit into the world [13].

Search for meaning (SFM) refers to the activity, intensity, and power of people’s efforts to develop or increase their knowledge of the meaning and purpose of their life [13].

POM helps alleviate anxiety and decrease the overreaction of the autonomic nervous system to emotional stress [21]. It has an inverse relationship with risk factors like substance abuse [22, 23]. The search for meaning positively correlates to factors such as depression, neurosis, and negative emotions [20]. Given the importance of meaning in life for human psychological well-being to overcome difficult living conditions, it should be constantly monitored to make the necessary interventions, such as meaning therapy in case of emptiness. This issue is especially important in difficult times and in stressed groups. Admission to university causes a change in social, family, and individual life, and hence it is considered a highly sensitive stage.

Along with these changes, new expectations and roles are formulated simultaneously with admission to the university. Such conditions are often accompanied by pressure and worry, affecting people’s performance and productivity [24]. Such exhausting conditions often pose questions about the meaning of life [25]. If students cannot find meaning in their lives, they will suffer from existential emptiness and may commit suicide to alleviate this situation [19].

Considering the importance of meaning in life for students’ mental health and suicide prevention, it should be continuously monitored in this group. This task is especially important in difficult situations like the COVID-19 pandemic. Students are one of the groups whose mental health has been affected and damaged more than the general population during this pandemic [6, 26, 27]. Therefore, in this research, we decided to evaluate the meaning of life of students during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted between September 12 and September 24, 2021, at the Tehran University of Medical Sciences (TUMS), in the capital of Iran. The statistical population of this study included all students who were studying at the University of Medical Sciences at the time of filling out the questionnaire. According to Mahdavinoor et al. [16], the mean overall score of meaning in life in four age groups of 18 to 21, 22 to 24, 25 to 27, and over 27 years old were 23.47, 24.06, 20.76, and 19.50, respectively (the standard deviation was 4.5 in each group). Therefore, with a confidence level of 1% and a test power of 90%, using G-power software, our minimum sample size for this study was calculated as 241 people. By including 10 more people to compensate for the possible dropout, the sample size was set at 251.

The questionnaire link was sent to university student groups on social networks such as Telegram and WhatsApp, and students who wished to complete the questionnaire filled it out. Due to the prevalence of the COVID-19 pandemic at the time of sampling, we had no face-to-face contact for sample collection.

A total of 325 students clicked on the questionnaire link, but only 251 students completed it (response rate: 91%). Forty-three students who filled out the questionnaires were from other universities, so we excluded them from the study. Finally, 208 questionnaires were reviewed.

The inclusion criteria were being a student of the Tehran University of Medical Sciences and being willing to participate in this study. The exclusion criterion was the incomplete filling of the questionnaire.

The data collection tool consisted of two sections. The first section assessed participants’ demographic information, including gender, age, marital status, belief in God, study major, name of the university, economic status of the family (high, medium, low), smoking habit, having a sibling, and history of mental disorder with 10 items. The second section was the meaning in life questionnaire (MLQ), the most widely used scale to measure the meaning of life in a variety of populations and cultures [17]. This questionnaire consists of two dimensions, including the POM and SOM in life. Each dimension has 5 items, which makes a total of 10 items. MLQ was developed and validated by Steger et al. [20]. Also, the validity and reliability of MLQ have been reviewed and approved by Naghiyaee et al. [17] and Mesrabadi et al. [28] in the general population. The questions are scored on a 7-point Likert scale (absolutely untrue, mostly untrue, somewhat untrue, cannot say true or false, somewhat true, mostly true, and absolutely true). The minimum and maximum scores for each dimension were 5 and 35, respectively. Higher scores in dimensions indicate that they are actively searching for meaning or have more meaning in their life.

The obtained data were analyzed by SPSS v. 26.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) using descriptive (frequency, mean, standard deviation) and inferential (Fisher exact-test, independent t-test, and 1-way ANOVA) statistics, and P<0.05 was considered as the significance level. We also examined the normal distribution of data by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test.

The Ethics Review Committee of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences approved this study with code No. IR.MAZUMA.REC.1400.205. The participants voluntarily took part in the study. In this research, no personal information was obtained from the participants, and their identities remained confidential.

3. Results

This study recruited 208 students from the Tehran University of Medical Sciences, 62 (29.8%) were male, and 146 (70.2%) were female. The mean±SD age of participants in this study was 21.50±2.74 years. The youngest subject was 19 years, and the oldest was 42 years old. Most participants (64.4%) were in the age range of 18-21 years. About 96.2% of the subjects were single, and 3.8% were married. Also, 92.8% of participants believed in God, and 7.2% were atheists. Besides, 52%9 were undergraduate students, and the remaining 47.1% were postgraduate. In terms of exercise, we divided subjects into two groups: <6 hours and >6 hours of exercise per week. Most participants (67.8%) did more than 6 hours of exercise per week. Thirteen participants (6.3%) were smokers. Regarding economic conditions, 84.6% of students had a moderate economic status. In our opinion, having a sibling was one of the variables affecting the meaning of life of students. About 55% of students had sisters, and 62.5% had brothers. Approximately 39% of students had a mental disorder, but the rest had no mental problems (Table 1).

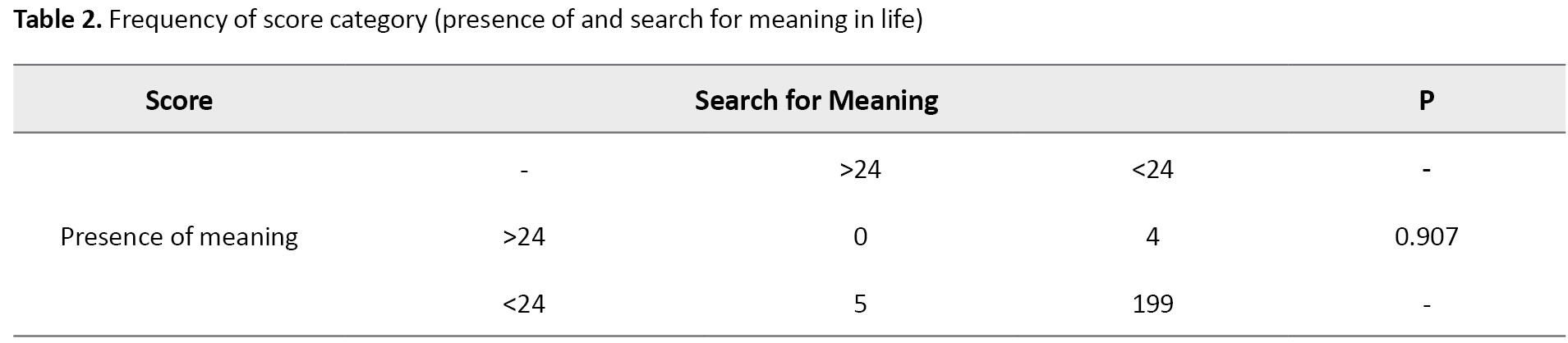

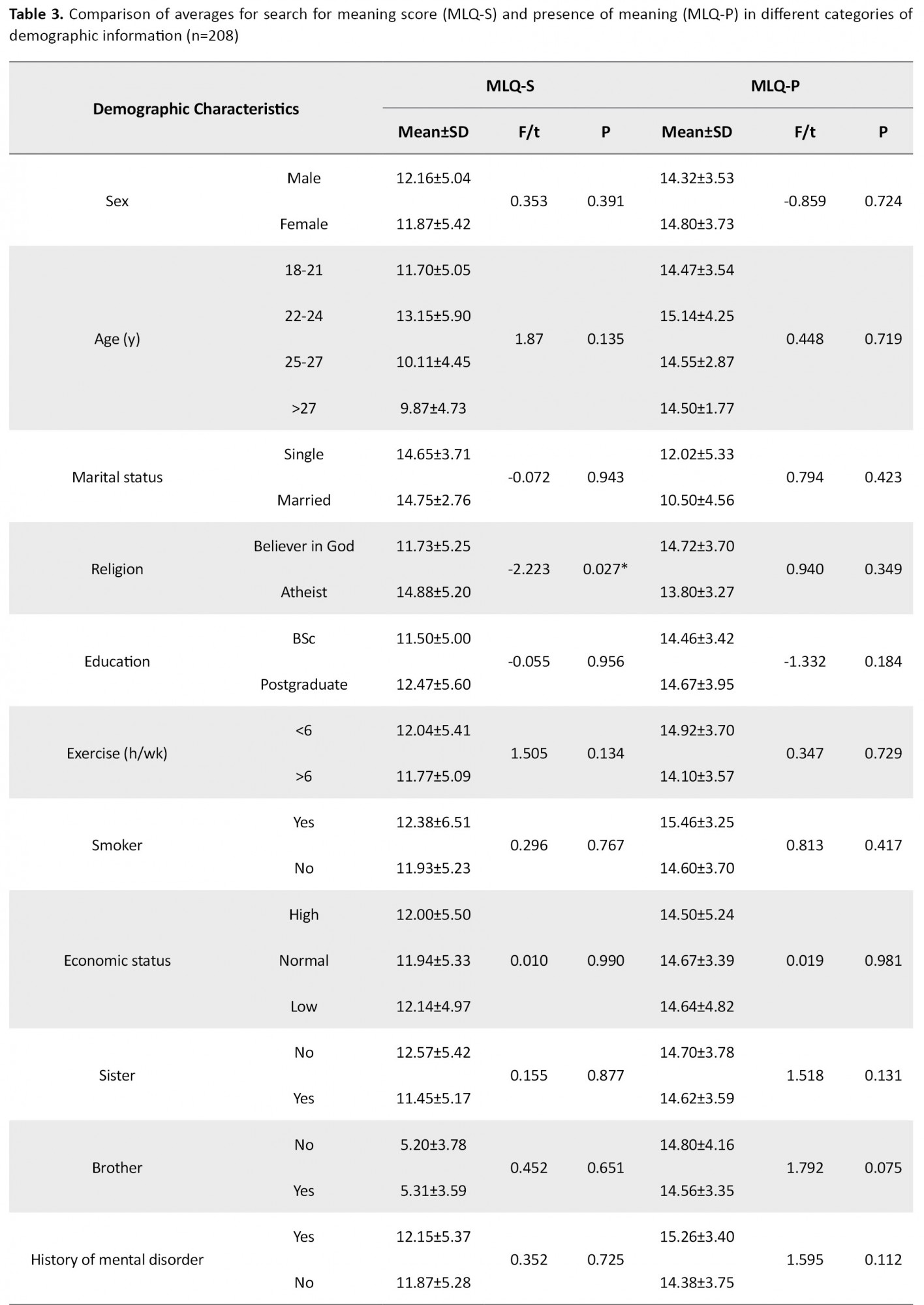

According to Table 2, 199 out of 208 students scored less than 24 in the POM in life and less than 24 in the SFM in life.

These findings indicate that they do not have a valuable meaning in life and do not search for meaning in life [29].

Five students scored more than 24 in SFM in life but less than 24 in POM in life. Perhaps they have no meaning in life but are looking for something or someone to give meaning or purpose to their life [30, 31, 32].

The remaining four students were those for whom the SFM in life score was less than 24 and the POM in life score was more than 24. This finding indicates that these students probably have a meaning that gives worth to their lives and therefore do not seek meaning in life [30, 31, 32].

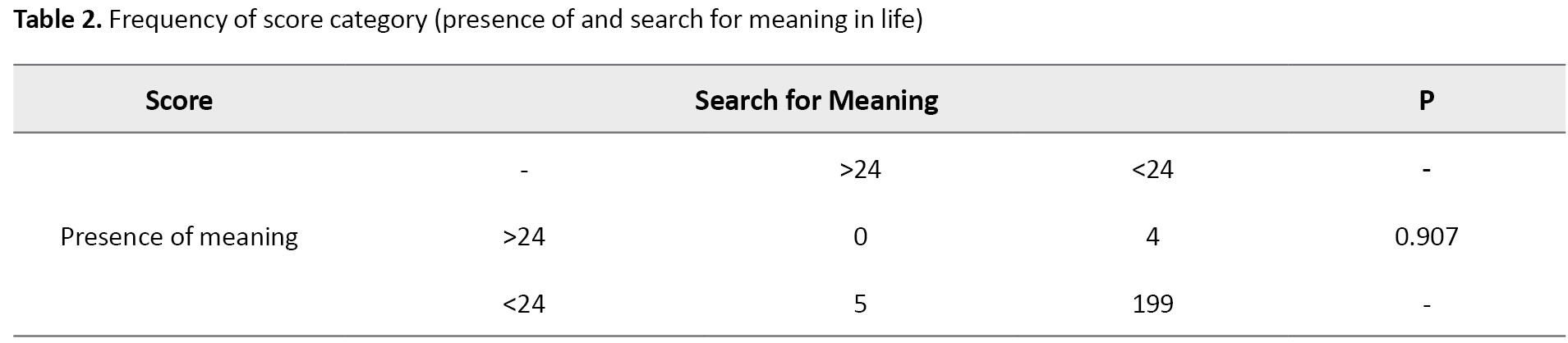

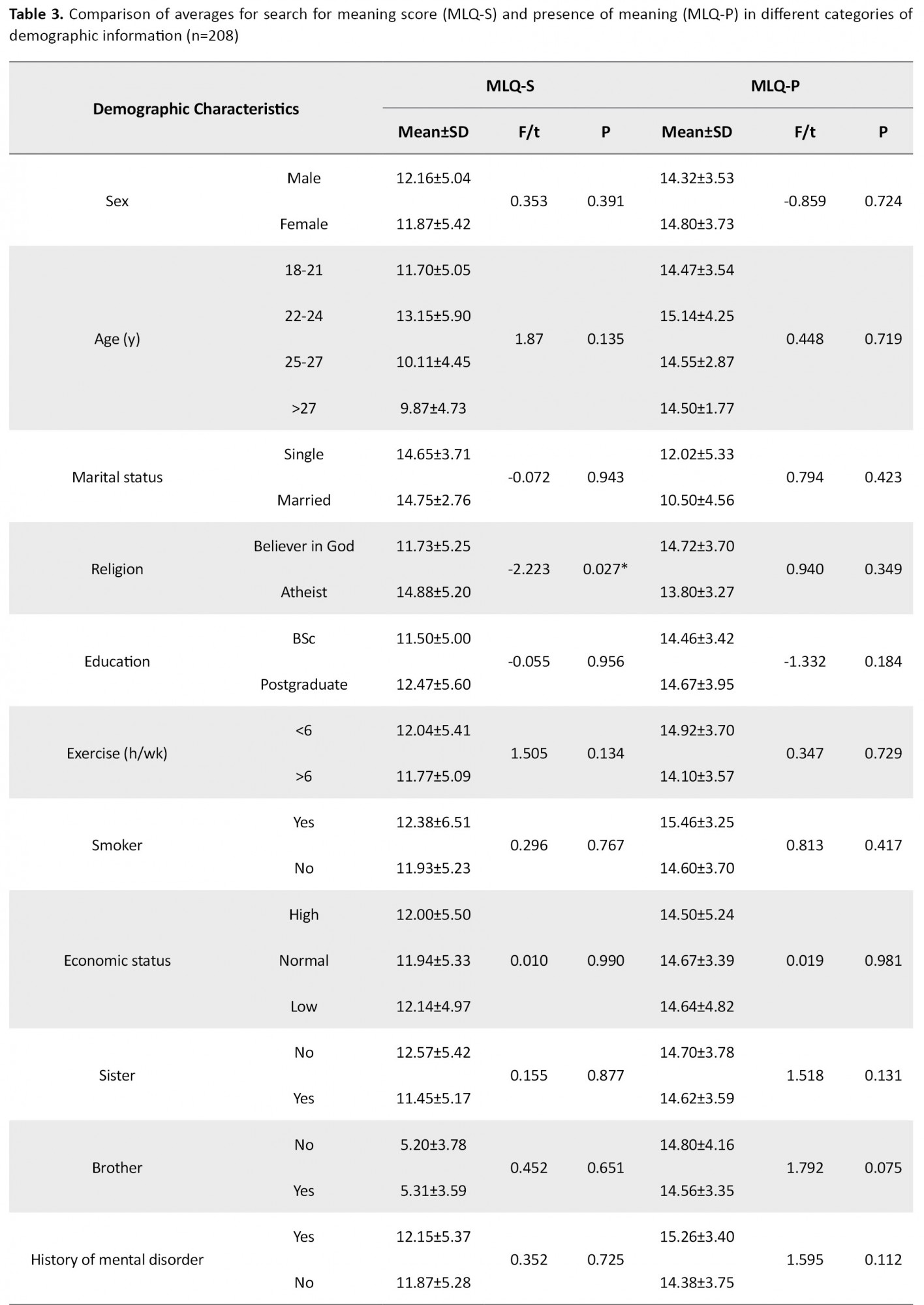

If the scores of POM in life and SFM in life for some people are more than 24, they feel that their lives have a valuable meaning and purpose, yet they are also looking for meaning. In this study, no individual experienced this condition (Figure 1) [30, 31, 32]. The Independent t-test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used to compare the mean scores of the SFM and POM in life components among different categories of demographic information variables. The results of these tests showed that the mean of these two scores was significantly different between men and women. Also, the scores of the SFM in life component and the POM in life were not significantly different between various age groups. These scores were also not significant in terms of marital status, level of education, physical activity, smoking, economic status, having a sister and brother, and history of mental disorder. However, the score of the SFM in life component was significantly different between the group who believed in God and the atheist group (P=0.027), so the average score of this index in the group of students who were atheists was higher than in those who believed in God. At the same time, the mean score of the POM in life between the two groups of believers and atheists was not significant (Table 3).

By examining the correlation between the score of the POM in the life component with the SFM in the life component, we found no significant relationship between these two components (r=0.045, P=0.517) (Figure 2). 4. Discussion

In this study, we assessed the meaning of life of students from Tehran University of Medical Sciences to predict their mental health status. The results showed that approximately 95% of students scored less than 24 in both dimensions of SFM and POM. This finding indicates that they not only lack a valuable meaning in life but also refuse to search for meaning in life. This condition is the worst psychological state a person can experience. These students have no hope for the future and are not optimistic about it, and they may feel depressed [30]. Such a situation is highly alarming. People who fail to find worthy meaning in life will experience an existential vacuum. Therefore, they may commit suicide to mitigate this distressing situation [31]. In a study by Sarokhani et al. [32] during the COVID-19 outbreak in a province of Iran, it was found that more than 24% of students had suicidal thoughts. When living conditions become difficult, one wonders whether this life is worth living. Why do I have to endure so much suffering? In this situation, if a person lacks a reason and purpose to continue living, s/he may think of committing suicide to get rid of all this sorrow. As indicated by Lew et al. [29] in a study on 2074 Chinese students, the meaning in life can be a protective factor against suicide. Viktor Frankl, the founder of logotherapy, was long detained in Nazi concentration camps. He recounts in his memoirs that only those who had meaning and purpose in life did manage to survive the harsh conditions of Nazi concentration camps [29, 30].

As a result, several interventions must be considered to help students find meaning in their life. Firstly, the reasons why students have no meaning in life and do not search for meaning in their life must be clarified. Secondly, there must be interventions to treat this emptiness. As mentioned earlier, logotherapy can positively affect meaning in life and quality of life [19]. Low scores in the two dimensions of the SFM in life and the POM in life among students of Tehran University of Medical Sciences can be due to different reasons. For example, high school students in Iran usually choose their field of study and future jobs under the pressure of family, the opinion of others, and the needs of society, not based on their interests and talents. Recently, it has been found that “socially prescribed” perfectionism, in which individuals try to meet and be satisfied with the standards of others, is associated with job burnout, depression, and lack of understanding of the meaning [33, 34, 35]. Modern lifestyle can also distract people from the true meaning of life, so many people can hardly define their purpose in life [18]. Further research is needed to identify other reasons why students do not feel meaning in their life.

In this study, there was no significant relationship between the presence of meaning in life and the search for meaning in life. According to previous research, the relationship between the SFM in life and the POM has been different in various cultures [36]. Several studies have shown that in individualistic cultures such as America, the search for and the presence of meaning are negatively correlated, and in collectivist cultures such as Japan, they are positively correlated [37]. However, in some studies, no correlation was found between the POM in life and the SFM in life [38] quoted from [39], which can perhaps be attributed to their cultural traits. Tehran University of Medical Sciences is located in the capital of Iran, has a high-quality education and research, and studying at it is free of charge. Therefore, many young people from all over Iran with different cultures come to study at this university. This cultural difference may be a factor in the lack of correlation between the search for meaning in life and the presence of meaning in life in this research.

Also, in this study, there was no association between the SFM in life or the POM in life with demographic information, including gender, age, marital status, level of education, smoking, physical activity, economic status, having a sibling, and history of mental disorder. Given that only 8 participants were married, perhaps the lack of connection between marital status and meaning in life could be explained. As Schnell showed, the meaning in life is higher among married people than single people [38]. This alignment of marriage and meaning in life can be justified by the existence of a sense of belonging in the family. Marriage can be considered the main source of receiving meaning [40, 41]. Regarding other variables, different research results are different, which can be attributed to cultural differences.

There was no significant difference in scores between believers in God and atheists in the POM in life. However, in the dimension of SFM, the score of atheists was higher than that of believers, and the difference was significant. Given that religion gives meaning to human life, this conclusion contradicts the previous presumptions of the authors. Religion makes people believe that the hardships and difficulties they endure in the world are in vain. Pious humans have a goal that makes them endure all the hardships to achieve it [42]. Religion may be a source that meets several needs for meaning in life. Religion forms a solid foundation of values and organizes daily activities, which directs decision-making in daily life, promotes desirable coping strategies, and provides social support for a religious community [40]. Of course, this result may be due to two reasons. First, religion is one of the sources of meaning in life. Family, nature, beloved ones, and other things can all play a role in meaning in life.

Given that the sample size of this study was small, it may not properly reflect the differences in this area. Second, in this study, students were asked whether or not they believed in God, and their religiosity or commitment was not evaluated. Certainly, people who believe in God differ in their religiosity and commitment to religion, and not all of them can be considered at the same level. Some people claim to believe in God because of the publicity and religiosity of the family, while this belief in God is not evident in their behavior. Future studies should assess the relationship between religiosity or religious commitment with meaning in life.

This study showed that the examined students would probably be highly vulnerable to mental illnesses due to lacking a valuable meaning in life. The concept of meaning in life may be the roadmap to overcoming a mental health crisis in difficult conditions such as epidemics, and it can probably play a role in this regard. Logotherapy can also positively affect the meaning and quality of life and may also be effective in preventing nihilism [34].

Study limitations

The small sample size of this study downgrades the generalizability of its findings. Depending on the type of data collection, students may not have been willing to fill out a questionnaire for various reasons, including a feeling of depression or isolation, which can affect the generalization of results.

5. Conclusion

The results of this study can indicate the catastrophe occurring at the Tehran University of Medical Sciences. More than 95% of students had no meaning in life and were not looking for a meaning to give value to their lives. According to the results, depression and suicidal ideation are probably high among these students. Despite the difficult living conditions in Iran and the psychological pressure on students, those studying at other universities are likely to be in a similar situation to students from the University of Tehran. In this regard, it is necessary to assess the meaning of life of students in other universities. Determining other dimensions of students’ mental health status in future research is also recommended. Policymakers must think about resolving this crisis as soon as possible; otherwise, student suicide rates will likely increase.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The Ethics Review Committee of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences approved this study (Code No. IR.MAZUMS.REC.1400.205). The participants voluntarily took part in the study. In this research, no personal information was obtained from the participants, and their identities remained confidential.

Funding

This study was funded by the Student Research Committee of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences.

Authors' contributions

Conceived the idea, designed the study, and collected the data: Seyyed Muhammad Mahdi Mahdavinoor; Statistical analysis: Aghil Mollaei; Wrote the final report and article: Seyyed Muhammad Mahdi Mahdavinoor and Seyyed Hatam Mahdavinoor; All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

In 2019, Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) turned into the greatest widespread infectious pneumonia in the world. Given the high prevalence of the disease, World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 pneumonia a pandemic. The virus quickly spread to all world countries and led to outbreaks in countries such as South Korea, Iran, and Italy [1, 2]. The disease affected many people worldwide and posed unique challenges in all aspects of life [3]. Restrictions imposed by the outbreak of COVID-19 affected people’s lifestyles and mental health status [4, 5]. Students were exposed to the psychological problems caused by this epidemic more than the general population due to their special status. Therefore, there is an urgent need to assess and monitor the unprecedented burden of mental health on students [6, 7, 8, 9]. The damage to students’ mental health can be prevented by addressing the underlying cause of the problem and implementing effective prevention programs [8].

The concept of “meaning in life” is directly related to mental health [10, 11, 12]. The meaning in life refers to the main purpose and concept of each person’s life. Many consider life’s meaning as the purpose of life [13, 14]. The meaning in life is the basic reason for human existence. Why does a human being not commit suicide despite all the hardships in life? Why do humans endure so much suffering? Why do people with incurable diseases such as cancer have to tolerate the adversities of the disease and its treatment? Is life worth all this suffering? The answer to these questions is related to the meaning of each person’s life. The reason for people’s existence is the meaning of their life; namely, the answer people give to the question of why they do not commit suicide.

The question of meaning in life arises when human beings are confronted with negative, bitter, painful, and gloomy aspects of their life. Is it natural for a person to think that life is worthwhile when faced with bitter moments of failure? Or what is it that makes life worth living [15]?

Usually, humans just try to enjoy life when they are not in a difficult situation. However, when the degree of suffering is greater than that of pleasure, a man asks whether it is worth living. Why should I not kill myself now that life’s suffering is more than its pleasure to free myself from pain and grief [16]? In this situation, humans seek a meaning that gives value to their life. The meaning in life is a vital psychological element for resilience to injury and disaster, which gives people the feeling that their life is important even in difficult times [17]. If people find such a meaning, they can endure suffering and sorrows, surviving the hardships and extremely difficult conditions of life [18]. However, if people fail to find meaning in their lives, they will undergo an existential vacuum. An existential vacuum is created in a person who has no meaning in life. This vacuity is a sensation of complete emptiness and lack of purpose to continue living. Therefore, suicide may seem appropriate to alleviate this distressing situation [19].

Meaning in life has two aspects [20]:

The Presence of meaning (POM) indicates whether people consider their lives important and purposeful. The term refers to understanding oneself and the world, including awareness of how to fit into the world [13].

Search for meaning (SFM) refers to the activity, intensity, and power of people’s efforts to develop or increase their knowledge of the meaning and purpose of their life [13].

POM helps alleviate anxiety and decrease the overreaction of the autonomic nervous system to emotional stress [21]. It has an inverse relationship with risk factors like substance abuse [22, 23]. The search for meaning positively correlates to factors such as depression, neurosis, and negative emotions [20]. Given the importance of meaning in life for human psychological well-being to overcome difficult living conditions, it should be constantly monitored to make the necessary interventions, such as meaning therapy in case of emptiness. This issue is especially important in difficult times and in stressed groups. Admission to university causes a change in social, family, and individual life, and hence it is considered a highly sensitive stage.

Along with these changes, new expectations and roles are formulated simultaneously with admission to the university. Such conditions are often accompanied by pressure and worry, affecting people’s performance and productivity [24]. Such exhausting conditions often pose questions about the meaning of life [25]. If students cannot find meaning in their lives, they will suffer from existential emptiness and may commit suicide to alleviate this situation [19].

Considering the importance of meaning in life for students’ mental health and suicide prevention, it should be continuously monitored in this group. This task is especially important in difficult situations like the COVID-19 pandemic. Students are one of the groups whose mental health has been affected and damaged more than the general population during this pandemic [6, 26, 27]. Therefore, in this research, we decided to evaluate the meaning of life of students during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted between September 12 and September 24, 2021, at the Tehran University of Medical Sciences (TUMS), in the capital of Iran. The statistical population of this study included all students who were studying at the University of Medical Sciences at the time of filling out the questionnaire. According to Mahdavinoor et al. [16], the mean overall score of meaning in life in four age groups of 18 to 21, 22 to 24, 25 to 27, and over 27 years old were 23.47, 24.06, 20.76, and 19.50, respectively (the standard deviation was 4.5 in each group). Therefore, with a confidence level of 1% and a test power of 90%, using G-power software, our minimum sample size for this study was calculated as 241 people. By including 10 more people to compensate for the possible dropout, the sample size was set at 251.

The questionnaire link was sent to university student groups on social networks such as Telegram and WhatsApp, and students who wished to complete the questionnaire filled it out. Due to the prevalence of the COVID-19 pandemic at the time of sampling, we had no face-to-face contact for sample collection.

A total of 325 students clicked on the questionnaire link, but only 251 students completed it (response rate: 91%). Forty-three students who filled out the questionnaires were from other universities, so we excluded them from the study. Finally, 208 questionnaires were reviewed.

The inclusion criteria were being a student of the Tehran University of Medical Sciences and being willing to participate in this study. The exclusion criterion was the incomplete filling of the questionnaire.

The data collection tool consisted of two sections. The first section assessed participants’ demographic information, including gender, age, marital status, belief in God, study major, name of the university, economic status of the family (high, medium, low), smoking habit, having a sibling, and history of mental disorder with 10 items. The second section was the meaning in life questionnaire (MLQ), the most widely used scale to measure the meaning of life in a variety of populations and cultures [17]. This questionnaire consists of two dimensions, including the POM and SOM in life. Each dimension has 5 items, which makes a total of 10 items. MLQ was developed and validated by Steger et al. [20]. Also, the validity and reliability of MLQ have been reviewed and approved by Naghiyaee et al. [17] and Mesrabadi et al. [28] in the general population. The questions are scored on a 7-point Likert scale (absolutely untrue, mostly untrue, somewhat untrue, cannot say true or false, somewhat true, mostly true, and absolutely true). The minimum and maximum scores for each dimension were 5 and 35, respectively. Higher scores in dimensions indicate that they are actively searching for meaning or have more meaning in their life.

The obtained data were analyzed by SPSS v. 26.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) using descriptive (frequency, mean, standard deviation) and inferential (Fisher exact-test, independent t-test, and 1-way ANOVA) statistics, and P<0.05 was considered as the significance level. We also examined the normal distribution of data by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test.

The Ethics Review Committee of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences approved this study with code No. IR.MAZUMA.REC.1400.205. The participants voluntarily took part in the study. In this research, no personal information was obtained from the participants, and their identities remained confidential.

3. Results

This study recruited 208 students from the Tehran University of Medical Sciences, 62 (29.8%) were male, and 146 (70.2%) were female. The mean±SD age of participants in this study was 21.50±2.74 years. The youngest subject was 19 years, and the oldest was 42 years old. Most participants (64.4%) were in the age range of 18-21 years. About 96.2% of the subjects were single, and 3.8% were married. Also, 92.8% of participants believed in God, and 7.2% were atheists. Besides, 52%9 were undergraduate students, and the remaining 47.1% were postgraduate. In terms of exercise, we divided subjects into two groups: <6 hours and >6 hours of exercise per week. Most participants (67.8%) did more than 6 hours of exercise per week. Thirteen participants (6.3%) were smokers. Regarding economic conditions, 84.6% of students had a moderate economic status. In our opinion, having a sibling was one of the variables affecting the meaning of life of students. About 55% of students had sisters, and 62.5% had brothers. Approximately 39% of students had a mental disorder, but the rest had no mental problems (Table 1).

According to Table 2, 199 out of 208 students scored less than 24 in the POM in life and less than 24 in the SFM in life.

These findings indicate that they do not have a valuable meaning in life and do not search for meaning in life [29].

Five students scored more than 24 in SFM in life but less than 24 in POM in life. Perhaps they have no meaning in life but are looking for something or someone to give meaning or purpose to their life [30, 31, 32].

The remaining four students were those for whom the SFM in life score was less than 24 and the POM in life score was more than 24. This finding indicates that these students probably have a meaning that gives worth to their lives and therefore do not seek meaning in life [30, 31, 32].

If the scores of POM in life and SFM in life for some people are more than 24, they feel that their lives have a valuable meaning and purpose, yet they are also looking for meaning. In this study, no individual experienced this condition (Figure 1) [30, 31, 32]. The Independent t-test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used to compare the mean scores of the SFM and POM in life components among different categories of demographic information variables. The results of these tests showed that the mean of these two scores was significantly different between men and women. Also, the scores of the SFM in life component and the POM in life were not significantly different between various age groups. These scores were also not significant in terms of marital status, level of education, physical activity, smoking, economic status, having a sister and brother, and history of mental disorder. However, the score of the SFM in life component was significantly different between the group who believed in God and the atheist group (P=0.027), so the average score of this index in the group of students who were atheists was higher than in those who believed in God. At the same time, the mean score of the POM in life between the two groups of believers and atheists was not significant (Table 3).

By examining the correlation between the score of the POM in the life component with the SFM in the life component, we found no significant relationship between these two components (r=0.045, P=0.517) (Figure 2). 4. Discussion

In this study, we assessed the meaning of life of students from Tehran University of Medical Sciences to predict their mental health status. The results showed that approximately 95% of students scored less than 24 in both dimensions of SFM and POM. This finding indicates that they not only lack a valuable meaning in life but also refuse to search for meaning in life. This condition is the worst psychological state a person can experience. These students have no hope for the future and are not optimistic about it, and they may feel depressed [30]. Such a situation is highly alarming. People who fail to find worthy meaning in life will experience an existential vacuum. Therefore, they may commit suicide to mitigate this distressing situation [31]. In a study by Sarokhani et al. [32] during the COVID-19 outbreak in a province of Iran, it was found that more than 24% of students had suicidal thoughts. When living conditions become difficult, one wonders whether this life is worth living. Why do I have to endure so much suffering? In this situation, if a person lacks a reason and purpose to continue living, s/he may think of committing suicide to get rid of all this sorrow. As indicated by Lew et al. [29] in a study on 2074 Chinese students, the meaning in life can be a protective factor against suicide. Viktor Frankl, the founder of logotherapy, was long detained in Nazi concentration camps. He recounts in his memoirs that only those who had meaning and purpose in life did manage to survive the harsh conditions of Nazi concentration camps [29, 30].

As a result, several interventions must be considered to help students find meaning in their life. Firstly, the reasons why students have no meaning in life and do not search for meaning in their life must be clarified. Secondly, there must be interventions to treat this emptiness. As mentioned earlier, logotherapy can positively affect meaning in life and quality of life [19]. Low scores in the two dimensions of the SFM in life and the POM in life among students of Tehran University of Medical Sciences can be due to different reasons. For example, high school students in Iran usually choose their field of study and future jobs under the pressure of family, the opinion of others, and the needs of society, not based on their interests and talents. Recently, it has been found that “socially prescribed” perfectionism, in which individuals try to meet and be satisfied with the standards of others, is associated with job burnout, depression, and lack of understanding of the meaning [33, 34, 35]. Modern lifestyle can also distract people from the true meaning of life, so many people can hardly define their purpose in life [18]. Further research is needed to identify other reasons why students do not feel meaning in their life.

In this study, there was no significant relationship between the presence of meaning in life and the search for meaning in life. According to previous research, the relationship between the SFM in life and the POM has been different in various cultures [36]. Several studies have shown that in individualistic cultures such as America, the search for and the presence of meaning are negatively correlated, and in collectivist cultures such as Japan, they are positively correlated [37]. However, in some studies, no correlation was found between the POM in life and the SFM in life [38] quoted from [39], which can perhaps be attributed to their cultural traits. Tehran University of Medical Sciences is located in the capital of Iran, has a high-quality education and research, and studying at it is free of charge. Therefore, many young people from all over Iran with different cultures come to study at this university. This cultural difference may be a factor in the lack of correlation between the search for meaning in life and the presence of meaning in life in this research.

Also, in this study, there was no association between the SFM in life or the POM in life with demographic information, including gender, age, marital status, level of education, smoking, physical activity, economic status, having a sibling, and history of mental disorder. Given that only 8 participants were married, perhaps the lack of connection between marital status and meaning in life could be explained. As Schnell showed, the meaning in life is higher among married people than single people [38]. This alignment of marriage and meaning in life can be justified by the existence of a sense of belonging in the family. Marriage can be considered the main source of receiving meaning [40, 41]. Regarding other variables, different research results are different, which can be attributed to cultural differences.

There was no significant difference in scores between believers in God and atheists in the POM in life. However, in the dimension of SFM, the score of atheists was higher than that of believers, and the difference was significant. Given that religion gives meaning to human life, this conclusion contradicts the previous presumptions of the authors. Religion makes people believe that the hardships and difficulties they endure in the world are in vain. Pious humans have a goal that makes them endure all the hardships to achieve it [42]. Religion may be a source that meets several needs for meaning in life. Religion forms a solid foundation of values and organizes daily activities, which directs decision-making in daily life, promotes desirable coping strategies, and provides social support for a religious community [40]. Of course, this result may be due to two reasons. First, religion is one of the sources of meaning in life. Family, nature, beloved ones, and other things can all play a role in meaning in life.

Given that the sample size of this study was small, it may not properly reflect the differences in this area. Second, in this study, students were asked whether or not they believed in God, and their religiosity or commitment was not evaluated. Certainly, people who believe in God differ in their religiosity and commitment to religion, and not all of them can be considered at the same level. Some people claim to believe in God because of the publicity and religiosity of the family, while this belief in God is not evident in their behavior. Future studies should assess the relationship between religiosity or religious commitment with meaning in life.

This study showed that the examined students would probably be highly vulnerable to mental illnesses due to lacking a valuable meaning in life. The concept of meaning in life may be the roadmap to overcoming a mental health crisis in difficult conditions such as epidemics, and it can probably play a role in this regard. Logotherapy can also positively affect the meaning and quality of life and may also be effective in preventing nihilism [34].

Study limitations

The small sample size of this study downgrades the generalizability of its findings. Depending on the type of data collection, students may not have been willing to fill out a questionnaire for various reasons, including a feeling of depression or isolation, which can affect the generalization of results.

5. Conclusion

The results of this study can indicate the catastrophe occurring at the Tehran University of Medical Sciences. More than 95% of students had no meaning in life and were not looking for a meaning to give value to their lives. According to the results, depression and suicidal ideation are probably high among these students. Despite the difficult living conditions in Iran and the psychological pressure on students, those studying at other universities are likely to be in a similar situation to students from the University of Tehran. In this regard, it is necessary to assess the meaning of life of students in other universities. Determining other dimensions of students’ mental health status in future research is also recommended. Policymakers must think about resolving this crisis as soon as possible; otherwise, student suicide rates will likely increase.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The Ethics Review Committee of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences approved this study (Code No. IR.MAZUMS.REC.1400.205). The participants voluntarily took part in the study. In this research, no personal information was obtained from the participants, and their identities remained confidential.

Funding

This study was funded by the Student Research Committee of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences.

Authors' contributions

Conceived the idea, designed the study, and collected the data: Seyyed Muhammad Mahdi Mahdavinoor; Statistical analysis: Aghil Mollaei; Wrote the final report and article: Seyyed Muhammad Mahdi Mahdavinoor and Seyyed Hatam Mahdavinoor; All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- Mahdavinoor SMM, Rafiei MH, Mahdavinoor SH. Mental health status of students during coronavirus pandemic outbreak: A cross-sectional study. Annals of Medicine and Surgery. 2022; 78:103739. [PMID]

- Kargar-Soleimanabad S, Dehbozorgi R, Mahdi Mahdavinoor SM. Psychosis due to anxiety related to COVID-19: A case report. Annals of Medicine and Surgery. 2022; 78:103795. [PMID]

- Esterwood E, Saeed SA. Past epidemics, natural disasters, covid19, and mental health: Learning from history as we deal with the present and prepare for the future. The Psychiatric Quarterly. 2020; 91(4):1121-33. [PMID]

- Bueno-Notivol J, Gracia-García P, Olaya B, Lasheras I, López-Antón R, Santabárbara J. Prevalence of depression during the COVID-19 outbreak: A meta-analysis of community-based studies. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology. 2021; 21(1):100196. [PMID]

- Ghafari R, Mirghafourvand M, Rouhi M, Osouli Tabrizi S. Mental health and its relationship with social support in Iranian students during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Psychology. 2021; 9(1):81. [PMID]

- Li Y, Wang A, Wu Y, Han N, Huang H. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of college students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology. 2021; 12:669119. [PMID]

- Naser AY, Dahmash EZ, Al-Rousan R, Alwafi H, Alrawashdeh HM, Ghoul I, et al. Mental health status of the general population, healthcare professionals, and university students during 2019 coronavirus disease outbreak in Jordan: A cross-sectional study. Brain and Behavior. 2020; 10(8):e01730. [PMID]

- Adhikari A, Sujakhu E, G C S, Zoowa S. Depression among Medical Students of a Medical College in Nepal during COVID-19 Pandemic: A descriptive cross-sectional study. JNMA; Journal of the Nepal Medical Association. 2021; 59(239):645-8. [PMID]

- Mishra J, Samanta P, Panigrahi A, Dash K, Behera MR, Das R. Mental health status, coping strategies during covid-19 pandemic among undergraduate students of healthcare profession. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 2021; 1-13. [PMID]

- Hedayati M, Khazaei M. An investigation of the relationship between depression, meaning in life and adult hope. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2014; 114:598-601. [DOI:10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.12.753]

- Zika S, Chamberlain K. On the relation between meaning in life and psychological well-being. British Journal of Psychology (London, England : 1953). 1992; 83( Pt 1):133-45. [PMID]

- Brassai L, Piko BF, Steger MF. Meaning in life: Is it a protective factor for adolescents’ psychological health? International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2011; 18(1):44-51. [PMID]

- Dezutter J, Casalin S, Wachholtz A, Luyckx K, Hekking J, Vandewiele W. Meaning in life: An important factor for the psychological well-being of chronically ill patients? Rehabilitation Psychology. 2013; 58(4):334-41. [PMID]

- Mahdavinoor SH, Alizadeh B. Meaning of Life in Islam, Christian, and Judaism. 1st ed. Golestan Province: Islamic Azad University of Aliabad-e Katoul; 2016. 217. [Link]

- Alizamani AA. [The meaning of meaning of life. philosophy of religion research (Persian)]. (Namah-i Hikmat). 2012; 5(1):59-89. [Link]

- Mahdavinoor SMM, Mollaei A, Abaresh Z, Mahdavinoor SH. [The meaning in life and its related factors in medical sciences students (Persian)]. Avicenna Interdisciplinary Journal of Religion and Health. 2022; 1(1):50-6. [Link]

- Naghiyaee M, Bahmani B, Asgari A. The Psychometric Properties of the Meaning in Life Questionnaire (MLQ) in patients with life-threatening illnesses. The Scientific World Journal. 2020; 2020:8361602. [PMID]

- Hill CE, Bowers G, Costello A, England J, Houston-Ludlam A, Knowlton G, et al. What’s what’s it all about? A qualitative study of undergraduate students’ students’ beliefs about meaning of life. Journal of Humanistic Psychology. 2013; 53(3):386-414. [DOI:10.1177/0022167813477733]

- Edwards MJ, Holden RR. Coping, meaning in life, and suicidal manifestations: Examining gender differences. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2001; 57(12):1517-34. [PMID]

- Steger MF, Frazier P, Oishi S, Kaler M. The meaning in life questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2006; 53(1):80. [DOI:10.1037/t01074-000]

- Ishida R, Okada M. Effects of a firm purpose in life on anxiety and sympathetic nervous activity caused by emotional stress: Assessment by psycho-physiological method. Stress and Health: Journal of the International Society for the Investigation of Stress. 2006; 22(4):275-81. [DOI:10.1002/smi.1095]

- Nicholson T, Higgins W, Turner P, James S, Stickle F, Pruitt T. The relation between meaning in life and the occurrence of drug abuse: A retrospective study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1994; 8(1):24-8. [DOI:10.1037/0893-164X.8.1.24]

- Shean GD, Fechtmann F. Purpose in life scores of student marihuana users. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1971; 27(1):112-3. [DOI:10.1002/1097-4679(197101)27:1<112::AID-JCLP2270270128>3.0.CO;2-D]

- Alizadeh-Navaei R, Hosseini SH. [Mental health status of Iranian students until 2011: A systematic review. (Persian)]. Clinical Excellence. 2014; 2(1):1-10. [Link]

- Carlin N. The meaning of life. Pastoral Psychology. 2016; 65(5):611-30. [DOI:10.1007/s11089-016-0704-6]

- Lee J, Solomon M, Stead T, Kwon B, Ganti L. Impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of US college students. BMC Psychology. 2021; 9(1):95. [PMID]

- Lyons Z, Wilcox H, Leung L, Dearsley O. COVID-19 and the mental well-being of Australian medical students: Impact, concerns and coping strategies used. Australasian Psychiatry. 2020; 28(6):649-52. [PMID]

- Mesrabadi J, Jafariyan S, Ostovar N. [Discriminative and construct validity of meaning in life questionnaire for Iranian students (Persian)]. International Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2013; 7(1):83-90. [Link]

- Steger M. MLQ-description-scoring-and-feedback-packet 2010

- Majdabadi Z. [The Meaning in Life Questionnaire (MLQ) (Persian)]. Jiurnal of Developmental Psychology (Iranian Psychologists). 2017; 13(51):331-3. [Link]

- Rose LM, Zask A, Burton LJ. Psychometric properties of the Meaning in Life Questionnaire (MLQ) in a sample of Australian adolescents. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth. 2017; 22(1):68-77. [DOI:10.1080/02673843.2015.1124791]

- Sarokhani M, Sayehmiri K, Ahmadi V, Mami S. Predicting suicidal thoughts using depression, anxiety and premenstrual syndrome patterns in female students of Ilam universities. Journal of Basic Research in Medical Sciences. 2021; 8(3):24-31. [Link]

- Lew B, Chistopolskaya K, Osman A, Huen JMY, Abu Talib M, Leung ANM. Meaning in life as a protective factor against suicidal tendencies in Chinese University students. BMC Psychiatry. 2020; 20(1):73. [PMID]

- Frankl VE. The Will to Meaning: Foundations and Applications of Logotherapy: Meridian; 1988. [Link]

- Kang KA, Shim JS, Jeon DG, Koh MS. [The effects of logotherapy on meaning in life and quality of life of late adolescents with terminal cancer (Korean)]. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing. 2009; 39(6):759-68. [PMID]

- Stoeber J, Childs JH. The assessment of self-oriented and socially prescribed perfectionism: Subscales make a difference. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2010; 92(6):577-85. [PMID]

- Schippers MC, Ziegler N. Life crafting as a way to find purpose and meaning in life. Frontiers in Psychology. 2019; 10:2778. [PMID]

- Birch H, Riby LM, McGann D. Perfectionism and PERMA: The benefits of otheroriented perfectionism. International Journal of Wellbeing. 2019; 9(1):20-42. [DOI:10.5502/ijw.v9i1.749]

- Xin-qiang W, Xiao-xin H, Fan Y, Da-jun Z. Structure and levels of meaning in life and its relationship with mental health in Chinese students aged 10 to 25. Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology. 2016; 10:1-12. [DOI:10.1017/prp.2016.7]

- Steger MF, Kawabata Y, Shimai S, Otake K. The meaningful life in Japan and the United States: Levels and correlates of meaning in life. Journal of Research in Personality. 2008; 42(3):660-78. [DOI:10.1016/j.jrp.2007.09.003]

- Gan Y. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the Meaning in Life Questionnaire. Chinese Journal of Mental Health. 2010; 24. [Link]

- Schnell T. The Sources of Meaning and Meaning in Life Questionnaire (SoMe): Relations to demographics and well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2009; 4(6):483-99. [DOI:10.1080/17439760903271074]

- Lambert NM, Stillman TF, Hicks JA, Kamble S, Baumeister RF, Fincham FD. To belong is to matter: Sense of belonging enhances meaning in life. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2013; 39(11):1418-27. [PMID]

Type of Study: Original Article |

Subject:

Education and Islamic Sciences

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |