Volume 11, Issue 4 (Autumn 2023)

Iran J Health Sci 2023, 11(4): 301-308 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Shahhosseini Z, Azizi M. Childbearing Recommendations for Women of Reproductive Age with Breast Cancer: A Policy Brief. Iran J Health Sci 2023; 11 (4) :301-308

URL: http://jhs.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-886-en.html

URL: http://jhs.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-886-en.html

Department of Midwifery, Sexual and Reproductive Health Research Center, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran. , marziehazizi70@gmail.com

Full-Text [PDF 706 kb]

(208 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (676 Views)

Full-Text: (92 Views)

1. Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) stands as the most prevalent cancer among women worldwide [1], and its incidence is increasing among childbearing‐aged women [2]. According to the National Cancer Institute Surveillance, <2.7% of BC occurred in women younger than 35 [3]. In general, BC in young women is characterized by a lower estrogen receptor expression and higher malignancy rate. So, after BC diagnosis, young women aged under 35 years are more likely to suffer from cancer-related recurrence and death than their older counterparts [4].

In recent decades, the rising trend of postponing pregnancy to the final years of the reproductive period and the growing number of young women diagnosed with BC encouraged some reproductive-aged women with BC to experience pregnancy after completing their cancer treatments [5, 6]. In addition, the declining fertility rate has recently been a substantial challenge in developing and developed countries, so many reproductive medicine and demography policymakers have attempted to address this challenge from different dimensions [7]. Studies show that the fertility rate among BC patients and survivors was considerably lower than that among general reproductive-aged women [8, 9].

Overall, cancer treatments such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy may hurt germ cells and negatively affect women’s reproductive status, causing serious concern for the healthcare community [2]. Although the results of an epidemiological study revealed no mortality increase associated with childbearing after the BC diagnosis, the fear of cancer recurrence and death is considerably high among reproductive-aged women with cancer and their families [4, 6].

In Iranian and Eastern cultures, childbearing brings joyfulness and completes women’s femininity. In some families, the childbearing issue is so vital that if women become infertile or catch diseases that lead to temporal infertility, their marital life might be threatened and ended [10]. So, young women diagnosed with BC have serious concerns regarding their childbearing status [11].

The literature review reveals no specific guidelines regarding the management of fertility status in reproductive-aged women who are diagnosed with cancer. Thus, physicians and other healthcare professionals lack enough clinical instructions or published guidelines to manage these women. Given the decline in fertility rate in Iran over recent decades and recognizing the pivotal role of young BC patients as a reproductive-aged group of women, this policy brief was conducted to assess the childbearing recommendations for these women. This policy brief emphasizes the critical need for policymakers to establish acceptable clinical guidelines regarding childbearing issues in women with BC.

2. Materials and Methods

The research question addressed in this study was to determine the childbearing recommended approaches in reproductive-aged women diagnosed with BC. To compile this policy brief study, researchers performed a comprehensive search in international databases such as Google Scholar, Scopus, Web of Sciences, Cochrane Library, UpToDate, BMJ Best Evidence, and PubMed, as well as Iranian national databases such as Scientific Information Database (SID) and Magiran. In addition, some general international health websites, including the World Health Organization (WHO), the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO), the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), and the Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs), were assessed to find published guidelines and packages in this topic. Finally, some specialized websites were explicitly searched to find related literature: American Cancer Society/American Society of Clinical Oncology Breast Cancer Survivorship Care Guideline, International Guidelines on Breast Cancer Care, European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO), National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), and Clinical Care Option (CCO).

During the search process, we considered no limitations regarding language, the study design, and publication year to enhance our accessibility to the related literature. The inclusion criteria in study selection were as follows: Each type of study that refers to childbearing or fertility issues in BC patients, studies published in valid journals or valid websites, and studies referring to fertility concerns of BC patients or BC survivors. However, studies conducted on women with other cancers were excluded from this study.

3. Results

The results are presented in three main categories: Myths, realities, and considerations surrounding childbearing among BC patients. Table 1 presents strategies with priorities and policy suggestions.

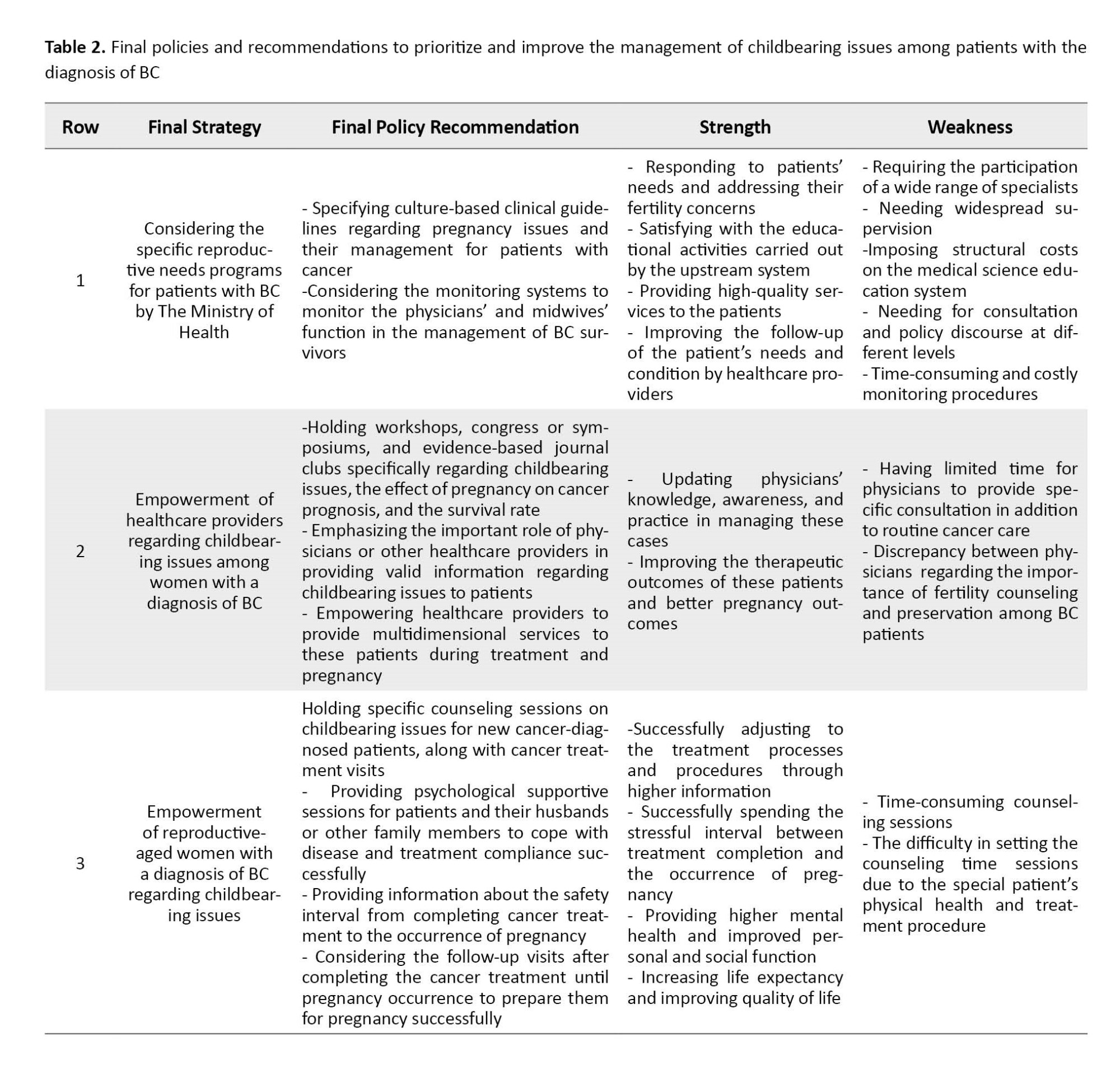

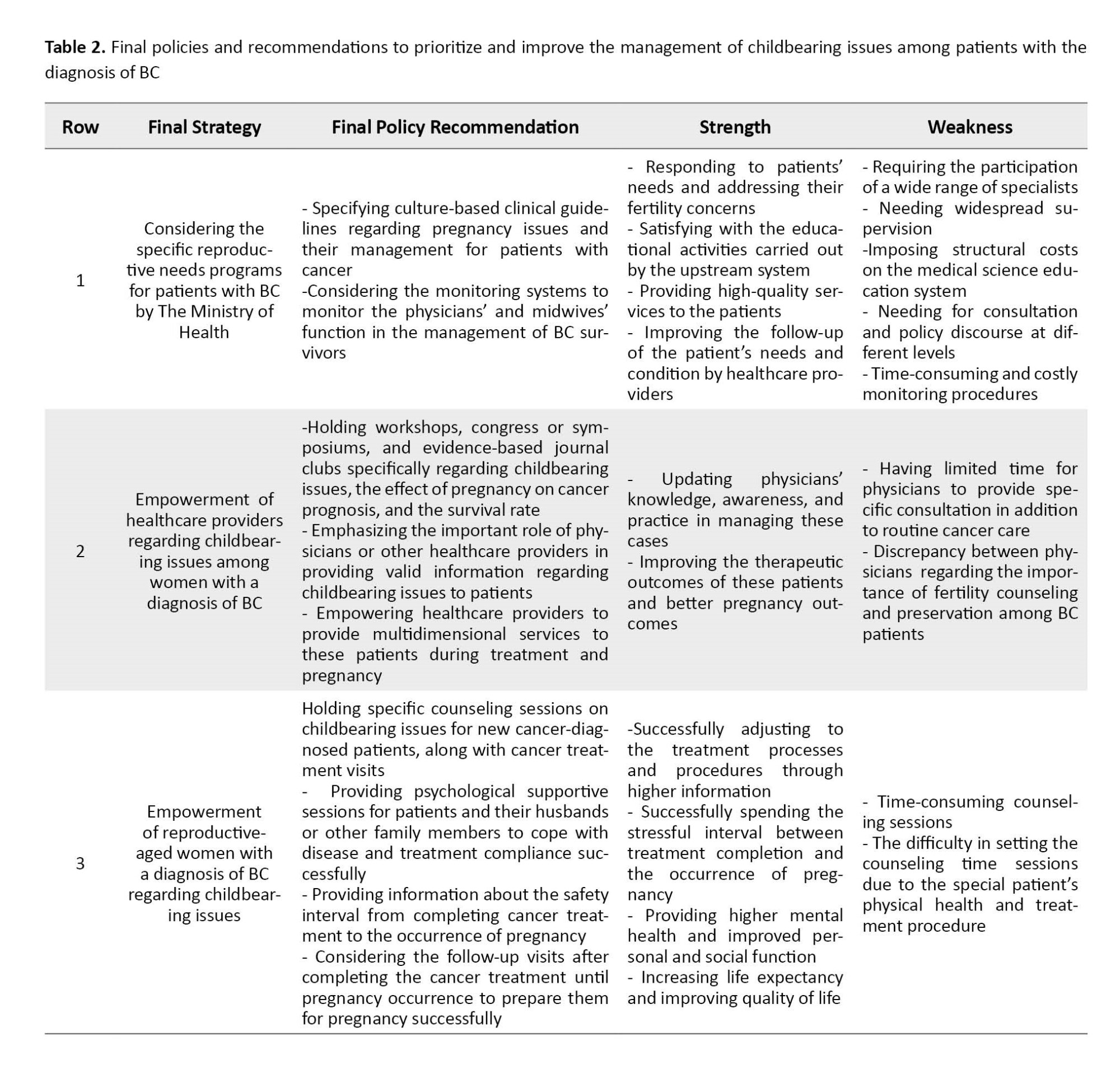

Table 2 lists strategies with higher emphasis, final policy recommendations, and their strengths and weaknesses.

Myths of childbearing in BC patients

The available information about the safety and feasibility of pregnancy after BC does not provide definitive evidence. Thus, pregnancy after BC is surrounded by myths, not facts. As the survival rate among young women with BC increases, This issue must be carefully assessed and clarified [12].

In the early 20th century, a common belief prevailed that BC conflicts with pregnancy and pregnancy in patients with BC are associated with decreased survival rates. Therapeutic abortion was a response to this belief that the hormonal response of pregnancy resulted in poor patient outcomes [13]. After all, BC is a hormonal tumor, and during pregnancy, female hormones increase. Therefore, there was a general concern that pregnancy can increase the risk of cancer recurrence among BC survivors [14]. Additionally, some psychological problems appeared in this regard. According to the results of an Iranian qualitative study to explore the psychological response of BC survivors, factors such as incompetence, despair of life, fear of disease recurrence, and fear of a child growing up without a mother had been the most common psychological reaction of BC survivors [15].

The transition to motherhood responsibilities accompanied by the fear of cancer recurrence and becoming an ill mother are some challenges among patients [16]. Concerns regarding transmitting the genes of cancer to newborns [17] and fear of losing a pregnancy and its subsequent grief were other BC patients’ challenges. Other most common challenges of BC survivors after childbirth were fear of inability to breastfeed due to mastectomy, failure to devote enough energy to taking care of the newborn and meeting the child’s needs, and the sense of dependency on family members, especially the husband’s support to perform motherhood responsibilities [18].

The wrong myths regarding the conflicts of childbearing after diagnosis of BC arise from the lack of patients’ health information regarding fertility potential. Actually, healthcare providers do not provide enough information to their patients [12].

As concerns about childbearing are added to the disease distress and its treatment challenges, the possibility of psychiatric disorders among patients rises. Therefore, counseling sessions must be held for newly diagnosed BC patients in their reproductive age to inform them about the chance of a healthy pregnancy after BC and possible disease outcomes.

Overall, the assessed studies had been conducted on a generally small sample size, and their population does not represent all young women with BC worldwide with different cultures and religions.

Realities of childbearing in BC patients

Some oncologists believe that in cases with cancer, the survival of patients is more important than preserving their fertility potential, so they do not present information about fertility preservation options and childbearing issues. Young BC patients have specific reproductive needs and concerns that physicians commonly do not satisfactorily address before initiating cancer treatment [19].

Many women experience considerable anxiety and distress regarding the possibility of infertility, conceiving, completing a healthy pregnancy, and childbirth. Overall, oncologists’ leading causes of concern were the possible effects of previous exposure to anticancer treatments on the fetus’s health, such as raising the risk of congenital abnormalities, delivery problems, or birth complications. Factors such as age and use of adjuvant chemotherapy are essential predictors of ovarian function among reproductive-aged women with BC [17].

In general, the reproductive health needs of patients as a vital survivorship issue should be assessed in the initiation of the treatment to reduce their psychological health-related fertility issues. They should be aware that, generally, the pregnancy rate may decrease after the BC treatment due to the possible effect of treatments on fertility potential. Still, this reality should not disappoint the young patients attempting to conceive after treatment, and various studies indicate that BC survivors can experience healthy pregnancies and have healthy children.

Considerations of childbearing in BC patients

In the 21st century, returning to normal life after cancer treatment should be considered an important issue in cancer care management [20]. Decisions about childbearing are complex and challenging after a BC diagnosis. Women experience a sense of uncertainty due to their indefinite disease statuses [4] and the potential long-term side effects of anticancer treatments, such as premature ovarian failure and subsequent disturbed fertility [20]. Generally, the pregnancy decision is affected by various important factors, such as the woman’s desire for more pregnancies, age, the statistical risk of early cancer recurrence, and the potential effect of estrogens on the risk of BC recurrence [21].

Despite recent studies showing that childbirth after the BC treatment is associated with no adverse effect on cancer recurrence or survival rate for early-stage BC patients, physicians advise patients to attempt to conceive at least two years after cancer treatments. However, this hypothesis is partially correct [22] because there is limited high-quality evidence to support this hypothesis. In addition, an assessment of the published guidelines showed that BC-related fertility was not assessed among these patients. Overall, studies regarding the fertility needs of patients and healthcare specialists’ knowledge and attitudes regarding the specific patient’s fertility needs are limited, and most of the available information has been retrieved through qualitative studies [23].

According to the maternal health care guideline published by the Iranian health system, no guideline exists to assess the pregnancy and childbearing issues for this high-risk population, and most of the policies have been designed for healthy women [24]. As these women generally have more than one health problem and there are no guidelines or educational packages in the primary health care units, it is necessary to prepare and validate a comprehensive service package that meets patients’ needs at different levels.

Two study authors recently cooperated with another research member’s team who designed and validated an educational pregnancy health package for BC survivors. Based on the qualitative study and literature review findings, a pregnancy health package for BC survivors was developed in seven chapters. The results of the validity or quality assessment of the package according to the six domains of the appraisal of guidelines for research and evaluation instrument II tool were reported as follows: The score for the scope and purpose domain was 95.55%, the stakeholder involvement domain was 89.16%, the score for the rigor of development domain was 92.97%, clarity of presentation domain was 94.44%, the score of applicability domain was 87.06%, and the score of editorial independence domain was calculated 93.75%. This package is a valuable resource for women who intend to get pregnant after completing BC treatment [11].

4. Discussion

This policy brief investigated the childbearing considerations among BC patients according to the most reliable evidence and reported them in three main categories: Myths, realities, and considerations. Overall, childbearing considerations are an essential issue that should be assessed in BC patients. These patients generally know little information regarding their fertility status, disease condition after pregnancy, and side effects of treatment on fertility consequences. In addition, because physicians generally ignore their information needs during treatment, these women would develop myths about fertility potentials [25]. These issues represented the lack of clinical and cultural-based guidelines regarding the management of these patients, leading to difficulty in assessing their fertility needs by physicians and other healthcare providers.

With the increasing survival rate due to improvements in screening procedures and advances in the treatment options among BC patients, they consider childbearing issues after BC treatment an essential clinical challenge [26]. In clinical practice, gynecologists and oncologists are faced with the challenge of educating about childbearing issues and cancer-related fertility matters to BC patients. In this policy brief study, the authors affirmed the necessity of considering educational courses and evidence-based journal clubs according to the latest published literature regarding pregnancy during cancer treatment and also pregnancy rate and outcomes among BC survivors.

One of the principal vital issues in reproductive-aged patients with BC who intend to experience childbearing after the treatment of BC is psychological concerns. These concerns comprise high levels of anxiety and distress regarding their ability to complete a healthy pregnancy and also fear of the possible adverse effects of adjuvant therapy on their fetus’s health and development, concerns regarding the transmission of the genes of cancer to newborn [17] and fear of stillbirth and its subsequent grief [27, 28]. In addition, fear of disease recurrence after experiencing pregnancy, fear of motherless children growing up, and concern regarding the child’s well-being after the mother’s death [18, 29] were other psychological issues reported by some of the BC survivors with experience of motherhood after treatment [18]. According to the results of an Iranian qualitative study on the psychological response of BC survivors, factors such as incompetence, despair of life, and fear of disease recurrence had been the most common psychological reaction of BC survivors [15]. The results of a qualitative study regarding the fertility concern of BC survivors during the perinatal period showed that they need more information and valuable resources about fertility and reproductive issues as they experience a higher possibility of psychological distress [30]. This policy brief also indicates the significant role of psychological counseling sessions during cancer treatment for young women with considerable distress regarding the fertility potential following cancer and its treatment.

When discussing “childbearing after BC” with the general population, many ask whether it is possible to experience pregnancy after cancer. This question shows the general population’s lack of knowledge and awareness, even women diagnosed with BC. One of the crucial actions to find these women’s concerns during cancer diagnosis is to perform a qualitative study in this regard. Also, this population’s lack of special programs is seriously felt in mass media and cyberspace. A literature review of a published qualitative study among Iranian BC patients, which assessed the perceived conflicts of BC patients, showed that the women’s concerns regarding pregnancy include fear of recurrence of cancer following pregnancy, fear of losing the pregnancy, fear of the disease’s effect on the consequences of pregnancy, all caused by their lack of knowledge about fertility issues after cancer [31]. Regarding the relationship between pregnancy after BC treatment and survival rate and disease recurrence, studies have indicated that BC survivors who conceived had higher survival and lowered BC recurrence than those who did not conceive [32, 33].

The results of this policy brief provide information about the possibility of childbearing after BC and safe delay intervals before conception [34]. For women with localized BC with a good prognosis, survival is unlikely to be compromised if pregnancy occurs within 6 months of diagnosis. To avoid the adverse effects of adjuvant treatment on birth outcomes, it is recommended to delay pregnancy for 6 to 12 months after completion of treatment because younger women have significantly lower survival rates and higher local and distant recurrence than older women. Individuals younger than 33 years are recommended to delay pregnancy for at least 3 years to reduce the risk of recurrence, while patients with lymph node involvement should postpone pregnancy for at least 5 years after treatment [22].

Conclusion

Altogether, there are no comprehensive guidelines for the management of childbearing issues among women with a diagnosis of cancer. However, in illnesses like cancer, reproductive-aged women not only need high-quality cancer treatment but also require multidimensional and multidisciplinary comprehensive supportive care regarding their fertility status to adjust to their treatment successfully. Also, as a suggestion, physicians and other healthcare providers should update their information to present complete responses to patients’ questions and main concerns regarding childbearing issues and the prognosis of illness after pregnancy.

In this current policy brief, we only reported the best evidence regarding pregnancy and childbearing issues in patients with BC with no systematic design. However, limited published evidence on this issue was another limitation that highlights the necessity for other studies in this regard. Although the authors of this study recently published a systematic review regarding the pregnancy rate and maternal and neonatal outcome among BC survivors, we suggest that other high-quality studies regarding the childbearing consideration among BC patients be performed to dispel the prevalent myths in this regard and improve the quality of life of these women.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This project tried to follow the Declaration of Helsinki as a statement of ethical principles for medical research on human subjects.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization: Zohreh Shahhosseini; Writing the original draft: Marzieh Azizi; Methodology, review and editing: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank the Sexual and Reproductive Health Research Center of the Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences.

References

Breast cancer (BC) stands as the most prevalent cancer among women worldwide [1], and its incidence is increasing among childbearing‐aged women [2]. According to the National Cancer Institute Surveillance, <2.7% of BC occurred in women younger than 35 [3]. In general, BC in young women is characterized by a lower estrogen receptor expression and higher malignancy rate. So, after BC diagnosis, young women aged under 35 years are more likely to suffer from cancer-related recurrence and death than their older counterparts [4].

In recent decades, the rising trend of postponing pregnancy to the final years of the reproductive period and the growing number of young women diagnosed with BC encouraged some reproductive-aged women with BC to experience pregnancy after completing their cancer treatments [5, 6]. In addition, the declining fertility rate has recently been a substantial challenge in developing and developed countries, so many reproductive medicine and demography policymakers have attempted to address this challenge from different dimensions [7]. Studies show that the fertility rate among BC patients and survivors was considerably lower than that among general reproductive-aged women [8, 9].

Overall, cancer treatments such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy may hurt germ cells and negatively affect women’s reproductive status, causing serious concern for the healthcare community [2]. Although the results of an epidemiological study revealed no mortality increase associated with childbearing after the BC diagnosis, the fear of cancer recurrence and death is considerably high among reproductive-aged women with cancer and their families [4, 6].

In Iranian and Eastern cultures, childbearing brings joyfulness and completes women’s femininity. In some families, the childbearing issue is so vital that if women become infertile or catch diseases that lead to temporal infertility, their marital life might be threatened and ended [10]. So, young women diagnosed with BC have serious concerns regarding their childbearing status [11].

The literature review reveals no specific guidelines regarding the management of fertility status in reproductive-aged women who are diagnosed with cancer. Thus, physicians and other healthcare professionals lack enough clinical instructions or published guidelines to manage these women. Given the decline in fertility rate in Iran over recent decades and recognizing the pivotal role of young BC patients as a reproductive-aged group of women, this policy brief was conducted to assess the childbearing recommendations for these women. This policy brief emphasizes the critical need for policymakers to establish acceptable clinical guidelines regarding childbearing issues in women with BC.

2. Materials and Methods

The research question addressed in this study was to determine the childbearing recommended approaches in reproductive-aged women diagnosed with BC. To compile this policy brief study, researchers performed a comprehensive search in international databases such as Google Scholar, Scopus, Web of Sciences, Cochrane Library, UpToDate, BMJ Best Evidence, and PubMed, as well as Iranian national databases such as Scientific Information Database (SID) and Magiran. In addition, some general international health websites, including the World Health Organization (WHO), the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO), the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), and the Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs), were assessed to find published guidelines and packages in this topic. Finally, some specialized websites were explicitly searched to find related literature: American Cancer Society/American Society of Clinical Oncology Breast Cancer Survivorship Care Guideline, International Guidelines on Breast Cancer Care, European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO), National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), and Clinical Care Option (CCO).

During the search process, we considered no limitations regarding language, the study design, and publication year to enhance our accessibility to the related literature. The inclusion criteria in study selection were as follows: Each type of study that refers to childbearing or fertility issues in BC patients, studies published in valid journals or valid websites, and studies referring to fertility concerns of BC patients or BC survivors. However, studies conducted on women with other cancers were excluded from this study.

3. Results

The results are presented in three main categories: Myths, realities, and considerations surrounding childbearing among BC patients. Table 1 presents strategies with priorities and policy suggestions.

Table 2 lists strategies with higher emphasis, final policy recommendations, and their strengths and weaknesses.

Myths of childbearing in BC patients

The available information about the safety and feasibility of pregnancy after BC does not provide definitive evidence. Thus, pregnancy after BC is surrounded by myths, not facts. As the survival rate among young women with BC increases, This issue must be carefully assessed and clarified [12].

In the early 20th century, a common belief prevailed that BC conflicts with pregnancy and pregnancy in patients with BC are associated with decreased survival rates. Therapeutic abortion was a response to this belief that the hormonal response of pregnancy resulted in poor patient outcomes [13]. After all, BC is a hormonal tumor, and during pregnancy, female hormones increase. Therefore, there was a general concern that pregnancy can increase the risk of cancer recurrence among BC survivors [14]. Additionally, some psychological problems appeared in this regard. According to the results of an Iranian qualitative study to explore the psychological response of BC survivors, factors such as incompetence, despair of life, fear of disease recurrence, and fear of a child growing up without a mother had been the most common psychological reaction of BC survivors [15].

The transition to motherhood responsibilities accompanied by the fear of cancer recurrence and becoming an ill mother are some challenges among patients [16]. Concerns regarding transmitting the genes of cancer to newborns [17] and fear of losing a pregnancy and its subsequent grief were other BC patients’ challenges. Other most common challenges of BC survivors after childbirth were fear of inability to breastfeed due to mastectomy, failure to devote enough energy to taking care of the newborn and meeting the child’s needs, and the sense of dependency on family members, especially the husband’s support to perform motherhood responsibilities [18].

The wrong myths regarding the conflicts of childbearing after diagnosis of BC arise from the lack of patients’ health information regarding fertility potential. Actually, healthcare providers do not provide enough information to their patients [12].

As concerns about childbearing are added to the disease distress and its treatment challenges, the possibility of psychiatric disorders among patients rises. Therefore, counseling sessions must be held for newly diagnosed BC patients in their reproductive age to inform them about the chance of a healthy pregnancy after BC and possible disease outcomes.

Overall, the assessed studies had been conducted on a generally small sample size, and their population does not represent all young women with BC worldwide with different cultures and religions.

Realities of childbearing in BC patients

Some oncologists believe that in cases with cancer, the survival of patients is more important than preserving their fertility potential, so they do not present information about fertility preservation options and childbearing issues. Young BC patients have specific reproductive needs and concerns that physicians commonly do not satisfactorily address before initiating cancer treatment [19].

Many women experience considerable anxiety and distress regarding the possibility of infertility, conceiving, completing a healthy pregnancy, and childbirth. Overall, oncologists’ leading causes of concern were the possible effects of previous exposure to anticancer treatments on the fetus’s health, such as raising the risk of congenital abnormalities, delivery problems, or birth complications. Factors such as age and use of adjuvant chemotherapy are essential predictors of ovarian function among reproductive-aged women with BC [17].

In general, the reproductive health needs of patients as a vital survivorship issue should be assessed in the initiation of the treatment to reduce their psychological health-related fertility issues. They should be aware that, generally, the pregnancy rate may decrease after the BC treatment due to the possible effect of treatments on fertility potential. Still, this reality should not disappoint the young patients attempting to conceive after treatment, and various studies indicate that BC survivors can experience healthy pregnancies and have healthy children.

Considerations of childbearing in BC patients

In the 21st century, returning to normal life after cancer treatment should be considered an important issue in cancer care management [20]. Decisions about childbearing are complex and challenging after a BC diagnosis. Women experience a sense of uncertainty due to their indefinite disease statuses [4] and the potential long-term side effects of anticancer treatments, such as premature ovarian failure and subsequent disturbed fertility [20]. Generally, the pregnancy decision is affected by various important factors, such as the woman’s desire for more pregnancies, age, the statistical risk of early cancer recurrence, and the potential effect of estrogens on the risk of BC recurrence [21].

Despite recent studies showing that childbirth after the BC treatment is associated with no adverse effect on cancer recurrence or survival rate for early-stage BC patients, physicians advise patients to attempt to conceive at least two years after cancer treatments. However, this hypothesis is partially correct [22] because there is limited high-quality evidence to support this hypothesis. In addition, an assessment of the published guidelines showed that BC-related fertility was not assessed among these patients. Overall, studies regarding the fertility needs of patients and healthcare specialists’ knowledge and attitudes regarding the specific patient’s fertility needs are limited, and most of the available information has been retrieved through qualitative studies [23].

According to the maternal health care guideline published by the Iranian health system, no guideline exists to assess the pregnancy and childbearing issues for this high-risk population, and most of the policies have been designed for healthy women [24]. As these women generally have more than one health problem and there are no guidelines or educational packages in the primary health care units, it is necessary to prepare and validate a comprehensive service package that meets patients’ needs at different levels.

Two study authors recently cooperated with another research member’s team who designed and validated an educational pregnancy health package for BC survivors. Based on the qualitative study and literature review findings, a pregnancy health package for BC survivors was developed in seven chapters. The results of the validity or quality assessment of the package according to the six domains of the appraisal of guidelines for research and evaluation instrument II tool were reported as follows: The score for the scope and purpose domain was 95.55%, the stakeholder involvement domain was 89.16%, the score for the rigor of development domain was 92.97%, clarity of presentation domain was 94.44%, the score of applicability domain was 87.06%, and the score of editorial independence domain was calculated 93.75%. This package is a valuable resource for women who intend to get pregnant after completing BC treatment [11].

4. Discussion

This policy brief investigated the childbearing considerations among BC patients according to the most reliable evidence and reported them in three main categories: Myths, realities, and considerations. Overall, childbearing considerations are an essential issue that should be assessed in BC patients. These patients generally know little information regarding their fertility status, disease condition after pregnancy, and side effects of treatment on fertility consequences. In addition, because physicians generally ignore their information needs during treatment, these women would develop myths about fertility potentials [25]. These issues represented the lack of clinical and cultural-based guidelines regarding the management of these patients, leading to difficulty in assessing their fertility needs by physicians and other healthcare providers.

With the increasing survival rate due to improvements in screening procedures and advances in the treatment options among BC patients, they consider childbearing issues after BC treatment an essential clinical challenge [26]. In clinical practice, gynecologists and oncologists are faced with the challenge of educating about childbearing issues and cancer-related fertility matters to BC patients. In this policy brief study, the authors affirmed the necessity of considering educational courses and evidence-based journal clubs according to the latest published literature regarding pregnancy during cancer treatment and also pregnancy rate and outcomes among BC survivors.

One of the principal vital issues in reproductive-aged patients with BC who intend to experience childbearing after the treatment of BC is psychological concerns. These concerns comprise high levels of anxiety and distress regarding their ability to complete a healthy pregnancy and also fear of the possible adverse effects of adjuvant therapy on their fetus’s health and development, concerns regarding the transmission of the genes of cancer to newborn [17] and fear of stillbirth and its subsequent grief [27, 28]. In addition, fear of disease recurrence after experiencing pregnancy, fear of motherless children growing up, and concern regarding the child’s well-being after the mother’s death [18, 29] were other psychological issues reported by some of the BC survivors with experience of motherhood after treatment [18]. According to the results of an Iranian qualitative study on the psychological response of BC survivors, factors such as incompetence, despair of life, and fear of disease recurrence had been the most common psychological reaction of BC survivors [15]. The results of a qualitative study regarding the fertility concern of BC survivors during the perinatal period showed that they need more information and valuable resources about fertility and reproductive issues as they experience a higher possibility of psychological distress [30]. This policy brief also indicates the significant role of psychological counseling sessions during cancer treatment for young women with considerable distress regarding the fertility potential following cancer and its treatment.

When discussing “childbearing after BC” with the general population, many ask whether it is possible to experience pregnancy after cancer. This question shows the general population’s lack of knowledge and awareness, even women diagnosed with BC. One of the crucial actions to find these women’s concerns during cancer diagnosis is to perform a qualitative study in this regard. Also, this population’s lack of special programs is seriously felt in mass media and cyberspace. A literature review of a published qualitative study among Iranian BC patients, which assessed the perceived conflicts of BC patients, showed that the women’s concerns regarding pregnancy include fear of recurrence of cancer following pregnancy, fear of losing the pregnancy, fear of the disease’s effect on the consequences of pregnancy, all caused by their lack of knowledge about fertility issues after cancer [31]. Regarding the relationship between pregnancy after BC treatment and survival rate and disease recurrence, studies have indicated that BC survivors who conceived had higher survival and lowered BC recurrence than those who did not conceive [32, 33].

The results of this policy brief provide information about the possibility of childbearing after BC and safe delay intervals before conception [34]. For women with localized BC with a good prognosis, survival is unlikely to be compromised if pregnancy occurs within 6 months of diagnosis. To avoid the adverse effects of adjuvant treatment on birth outcomes, it is recommended to delay pregnancy for 6 to 12 months after completion of treatment because younger women have significantly lower survival rates and higher local and distant recurrence than older women. Individuals younger than 33 years are recommended to delay pregnancy for at least 3 years to reduce the risk of recurrence, while patients with lymph node involvement should postpone pregnancy for at least 5 years after treatment [22].

Conclusion

Altogether, there are no comprehensive guidelines for the management of childbearing issues among women with a diagnosis of cancer. However, in illnesses like cancer, reproductive-aged women not only need high-quality cancer treatment but also require multidimensional and multidisciplinary comprehensive supportive care regarding their fertility status to adjust to their treatment successfully. Also, as a suggestion, physicians and other healthcare providers should update their information to present complete responses to patients’ questions and main concerns regarding childbearing issues and the prognosis of illness after pregnancy.

In this current policy brief, we only reported the best evidence regarding pregnancy and childbearing issues in patients with BC with no systematic design. However, limited published evidence on this issue was another limitation that highlights the necessity for other studies in this regard. Although the authors of this study recently published a systematic review regarding the pregnancy rate and maternal and neonatal outcome among BC survivors, we suggest that other high-quality studies regarding the childbearing consideration among BC patients be performed to dispel the prevalent myths in this regard and improve the quality of life of these women.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This project tried to follow the Declaration of Helsinki as a statement of ethical principles for medical research on human subjects.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization: Zohreh Shahhosseini; Writing the original draft: Marzieh Azizi; Methodology, review and editing: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank the Sexual and Reproductive Health Research Center of the Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences.

References

- Assi HA, Khoury KE, Dbouk H, Khalil LE, Mouhieddine TH, El Saghir NS. Epidemiology and prognosis of breast cancer in young women. Journal of Thoracic Disease. 2013; 5(Suppl 1):S2-8. [DOI:10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2013.05.24] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Huang SM, Tseng LM, Lai JC, Lien PJ, Chen PH. Infertility-related knowledge in childbearing-age women with breast cancer after chemotherapy. International Journal of Nursing Practice. 2019; 25(5):e12765. [DOI:10.1111/ijn.12765] [PMID]

- Darwish AD, Helal AM, Aly El-Din NH, Solaiman LL, Amin A. Breast cancer in women aging 35 years old and younger: The Egyptian national cancer institute (NCI) experience. Breast. 2017; 31:1-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.breast.2016.09.018] [PMID]

- Gonçalves V, Sehovic I, Quinn G. Childbearing attitudes and decisions of young breast cancer survivors: A systematic review. Human Reproduction Update. 2014; 20(2):279-92. [DOI:10.1093/humupd/dmt039] [PMID]

- Pagani O, Ruggeri M, Manunta S, Saunders C, Peccatori F, Cardoso F, et al. Pregnancy after breast cancer: Are young patients willing to participate in clinical studies? Breast. 2015; 24(3):201-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.breast.2015.01.005] [PMID]

- Ruggeri M, Pagan E, Bagnardi V, Bianco N, Gallerani E, Buser K, et al. Fertility concerns, preservation strategies and quality of life in young women with breast cancer: Baseline results from an ongoing prospective cohort study in selected European Centers. Breast. 2019; 47:85-92. [DOI:10.1016/j.breast.2019.07.001] [PMID]

- Linkeviciute A, Boniolo G, Chiavari L, Peccatori FA. Fertility preservation in cancer patients: The global framework. Cancer Treatment Reviews. 2014; 40(8):1019-27. [DOI:10.1016/j.ctrv.2014.06.001] [PMID]

- Hartman M, Liu J, Czene K, Miao H, Chia KS, Salim A, et al. Birth rates among female cancer survivors: A population-based cohort study in Sweden. Cancer. 2013; 119(10):1892-9. [DOI:10.1002/cncr.27929] [PMID]

- Lambertini M, Goldrat O, Clatot F, Demeestere I, Awada A. Controversies about fertility and pregnancy issues in young breast cancer patients: Current state of the art. Current Opinion in Oncology. 2017; 29(4):243-52. [DOI:10.1097/CCO.0000000000000380] [PMID]

- Behboodi-Moghadam Z, Salsali M, Eftekhar-Ardabily H, Vaismoradi M, Ramezanzadeh F. Experiences of infertility through the lens of Iranian infertile women: A qualitative study. Japan Journal of Nursing Science. 2013; 10(1):41-6. [DOI:10.1111/j.1742-7924.2012.00208.x] [PMID]

- Azizi M, Ebrahimi E, Moghadam ZB, Shahhosseini Z, Modarres M. Pregnancy health among breast cancer survivors: Development and validation of an educational package in Iran. Journal of Cancer Education. 2023; 38(4):1373-82. [DOI:10.1007/s13187-023-02275-y] [PMID]

- Pagani O, Azim H Jr. Pregnancy after breast cancer: Myths and facts. Breast Care. 2012; 7(3):210-4. [DOI:10.1159/000339885] [PMID]

- America Ppfo. Myths about abortion and breast cancer. 2013:1-6.

- Razeti MG, Spinaci S, Spagnolo F, Massarotti C, Lambertini M. How I perform fertility preservation in breast cancer patients. ESMO Open. 2021; 6(3):100112. [DOI:10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100112] [PMID]

- Masoomi T, Shafaroudi N, Kamali M, Hasani A, Omrani pour R. [Psychological responses to breast cancer: A qualitative study (Persian)]. Journal of Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences. 2013; 20(1):84-92. [Link]

- Arès I, Lebel S, Bielajew C. The impact of motherhood on perceived stress, illness intrusiveness and fear of cancer recurrence in young breast cancer survivors over time. Psychology & Health. 2014; 29(6):651-70. [DOI:10.1080/08870446.2014.881998] [PMID]

- Alipour S, Omranipour R. Diseases of the breast during pregnancy and lactation. Berlin: Springer; 2020. [DOI:10.1007/978-3-030-41596-9]

- Wan C, Ares I, Gareau A, Collins KA, Lebel S, Bielajew C. Motherhood and well-being in young breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Management. 2018; 7(2):BMT02. [DOI:10.2217/bmt-2017-0015]

- Camp-Sorrell D. Cancer and its treatment effect on young breast cancer survivors. Seminars in Oncology Nursing. 2009; 25(4):251-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.soncn.2009.08.002] [PMID]

- Lambertini M, Blondeaux E, Bruzzone M, Perachino M, Anderson RA, de Azambuja E, et al. Pregnancy after breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2021; 39(29):3293-305. [DOI:10.1200/JCO.21.00535] [PMID]

- Durrani S, Akbar S, Heena H. Breast cancer during pregnancy. Cureus. 2018; 10(7):e2941. [DOI:10.7759/cureus.2941] [PMID]

- Peccatori FA, Azim HA Jr, Orecchia R, Hoekstra HJ, Pavlidis N, Kesic V, et al. Cancer, pregnancy and fertility: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Annals of Oncology. 2013; 24(Suppl 6):vi160-70. [DOI:10.1093/annonc/mdt199] [PMID]

- Zhang H, Wang G, Jiang B, Cao M, Jiang Q, Yin L, et al. The knowledge, attitude, and self-reported behaviors of oncology physicians regarding fertility preservation in adult cancer patients. Journal of Cancer Education. 2020; 35(6):1119-27. [DOI:10.1007/s13187-019-01567-6] [PMID]

- Kharaghani R, Shariati M, Yunesian M, Keramat A, Moghisi A. The Iranian integrated maternal health care guideline based on evidence-based medicine and American guidelines: A comparative study. Modern Care Journal. 2016; 13(2):e9455. [DOI:10.17795/modernc.9455]

- Torres-Castaño A, Perestelo-Pérez L, Duarte-Díaz A, Toledo-Chávarri A, Ramos-García V, Álvarez-Pérez Y, et al. Information needs and research priorities for fertility preservation in women with breast cancer: Patients and experts' perspectives. European Journal of cancer Care. 2021; 30(1):e13359. [DOI:10.1111/ecc.13359] [PMID]

- Burstein HJ, Curigliano G, Loibl S, Dubsky P, Gnant M, Poortmans P, et al. Estimating the benefits of therapy for early-stage breast cancer: The St. Gallen international consensus guidelines for the primary therapy of early breast cancer 2019. Annals of Oncology. 2019; 30(10):1541-57. [DOI:10.1093/annonc/mdz235] [PMID]

- Kirkman M, Winship I, Stern C, Neil S, Mann GB, Fisher JR. Women's reflections on fertility and motherhood after breast cancer and its treatment. European Journal of Cancer Care. 2014; 23(4):502-13. [DOI:10.1111/ecc.12163] [PMID]

- Azim HA Jr, Santoro L, Pavlidis N, Gelber S, Kroman N, Azim H, Peccatori FA. Safety of pregnancy following breast cancer diagnosis: A meta-analysis of 14 studies. European Journal of Cancer. 2011; 47(1):74-83. [DOI:10.1016/j.ejca.2010.09.007] [PMID]

- Faccio F, Mascheroni E, Ionio C, Pravettoni G, Alessandro Peccatori F, Pisoni C, et al. Motherhood during or after breast cancer diagnosis: A qualitative study. European Journal of Cancer Care. 2020; 29(2):e13214. [DOI:10.1111/ecc.13214] [PMID]

- Vanstone RN, Fergus K, Ladhani NNN, Warner E. Reproductive concerns and fear of cancer recurrence: A qualitative study of women's experiences of the perinatal period after cancer. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2021; 21(1):738. [DOI:10.1186/s12884-021-04208-3] [PMID]

- Ghaemi SZ, Keshavarz Z, Tahmasebi S, Akrami M, Heydari ST. Conflicts women with breast cancer face with: A qualitative study. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care. 2019; 8(1):27-36. [DOI:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_272_18] [PMID]

- Kroman N, Jensen MB, Wohlfahrt J, Ejlertsen B; Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group. Pregnancy after treatment of breast cancer--a population-based study on behalf of Danish breast cancer cooperative group. Acta Oncologica. 2008; 47(4):545-9. [DOI:10.1080/02841860801935491] [PMID]

- Gerstl B, Sullivan E, Ives A, Saunders C, Wand H, Anazodo A. Pregnancy outcomes after a breast cancer diagnosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Breast Cancer. 2018; 18(1):e79-e88. [DOI:10.1016/j.clbc.2017.06.016] [PMID]

- Kranick JA, Schaefer C, Rowell S, Desai M, Petrek JA, Hiatt RA, et al. Is pregnancy after breast cancer safe? The Breast Journal. 2010; 16(4):404-11. [DOI:10.1111/j.1524-4741.2010.00939.x] [PMID]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |