Volume 13, Issue 2 (Spring 2025)

Iran J Health Sci 2025, 13(2): 85-96 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Habibnejad Roushan F, Azizi M, Habibi F, Khani S. Female and Male Myths about Sexuality: A Systematic Review. Iran J Health Sci 2025; 13 (2) :85-96

URL: http://jhs.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-958-en.html

URL: http://jhs.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-958-en.html

Department of Midwifery and Reproductive Health, Sexual and Reproductive Health Research Center, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran. , khanisog343@gmail.com

Full-Text [PDF 1119 kb]

(114 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (387 Views)

Full-Text: (2 Views)

Introduction

Individuals’ beliefs about sexuality are every so often established on a series of exaggerated, incorrect and unscientific concepts, symbols and emotions, such as a sense of guilt, feelings of inadequacy, anxiety, and even fear of failure regarding some sexual issues they deem to be true. These erroneous beliefs and concepts can affect mindsets and behaviors about male and female sexuality [1]. Sexual myths are also determined by various factors, including personal beliefs, attitudes and values about sex, which are fundamentally shaped by the surrounding cultures [2]. Given that, sexual beliefs are typically impacted by cultural background, educational and social influence, as well as personal experience [3]. Sexuality is currently forbidden in some Asian nations, including China, wherein sex education in schools has been historically limited, so it has been, to date, ignored by women and not taken seriously by healthcare providers (HCPs) [4].

At present, the healthcare system in Iran does not meet women’s sexual needs [5]. Notably, there are myths about sexuality altering sexual satisfaction, encompassing personal and relational components, which include the perceived compatibility of sexual desire and beliefs, values, and attitudes. The effect of sexual myths and awareness of sexual desires on the marital satisfaction of couples has been proven. Sexual compatibility in marriage is an integral part of the marital process and significantly affects the satisfaction of the marriage and the marital relationship. Although the absence of sexual function problems has a positive impact on marriage, it is argued that the experience of these problems negatively affects marriage, undermining positive feelings and marital intimacy [6, 7, 8, 9, 10]. From this perspective, there is a need to investigate sexual and reproductive health needs in different societies and cultural contexts, demanding counseling centers promoting women’s sexual and reproductive healthcare services, given the high frequency of women being referred to medical facilities to deal with sexual problems. If HCPs know partly about sexual myths, they can help treat sexual and reproductive disorders in the early stages [5]. Thus, the Iranian Ministry of Health and Medical Education has recently created sexual health clinics affiliated with the universities of medical sciences. Reflection on the related literature reveals no review study assessing myths about female and male sexuality, to the best of the author’s knowledge. As wrong sexual myths can have adverse effects on couples’ sexual health, this review study aimed to fill this gap and review the most common myths around sexuality among women and men.

Materials and Methods

This systematic review of the existing literature on female and male myths about sexuality was fulfilled in five steps: Addressing the research question, searching and retrieving the relevant articles, assessing the methodological quality of the included studies, summarizing the evidence and results, and interpreting and discussing the findings, delineated as follows. The research question was then developed based on the PECO components, viz. population (P) (the type of participants), exposure (E) (sexual myths), comparator (C) (not applicable) and outcome (the dependent variable).

Addressing research question

Initially, the main research question in this study was addressed as follows: What are the female and male myths about sexuality?

Searching and retrieving relevant articles

Two researchers Faezeh Habibnejad & Marzieh Azizi independently conducted an online search on the databases of PubMed, Google Scholar, Magiran, Scopus, PsycINFO, IranDoc, Ovid, ProQuest, Scientific Information Database (SID) and the Cochrane Library. The search process commenced on December 3 and ended on December 21, 2022. The search was done in Persian and English. The medical subject heading (MeSH) was also utilized to find the related keywords, viz., “sexual myth,” “sexual beliefs,” “wrong beliefs” and “dysfunctional sexual beliefs.” The search process was mainly based on systematic search, using the following keywords: (“Sexual myth” [title/abstract]) OR (“sexual beliefs” [title/abstract]) “dysfunctional sexual beliefs” [title/abstract], (“sexual myths” [title/abstract]) OR (“sexual beliefs” [title/abstract]) AND [(“wrong beliefs”)) OR (“incorrect beliefs”)], [“sexual myths” “sexual beliefs” (title/abstract)]. The articles were then reviewed and the most relevant ones meeting the inclusion criteria were selected.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Two researchers Faezeh Habibnejad & Marzieh Azizi independently screened the article titles and abstracts. If a study was relevant, the full-text manuscript was reviewed for further assessments according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The search was conducted in Persian and English, and studies in other languages were not included. The cross-sectional studies that reported myths about sexuality, as well as those with no year of publication limitation, were also included. Some articles were eliminated for no access to their full texts, recruiting interventional designs, doing qualitative analysis, having the NOS score <5 and so on.

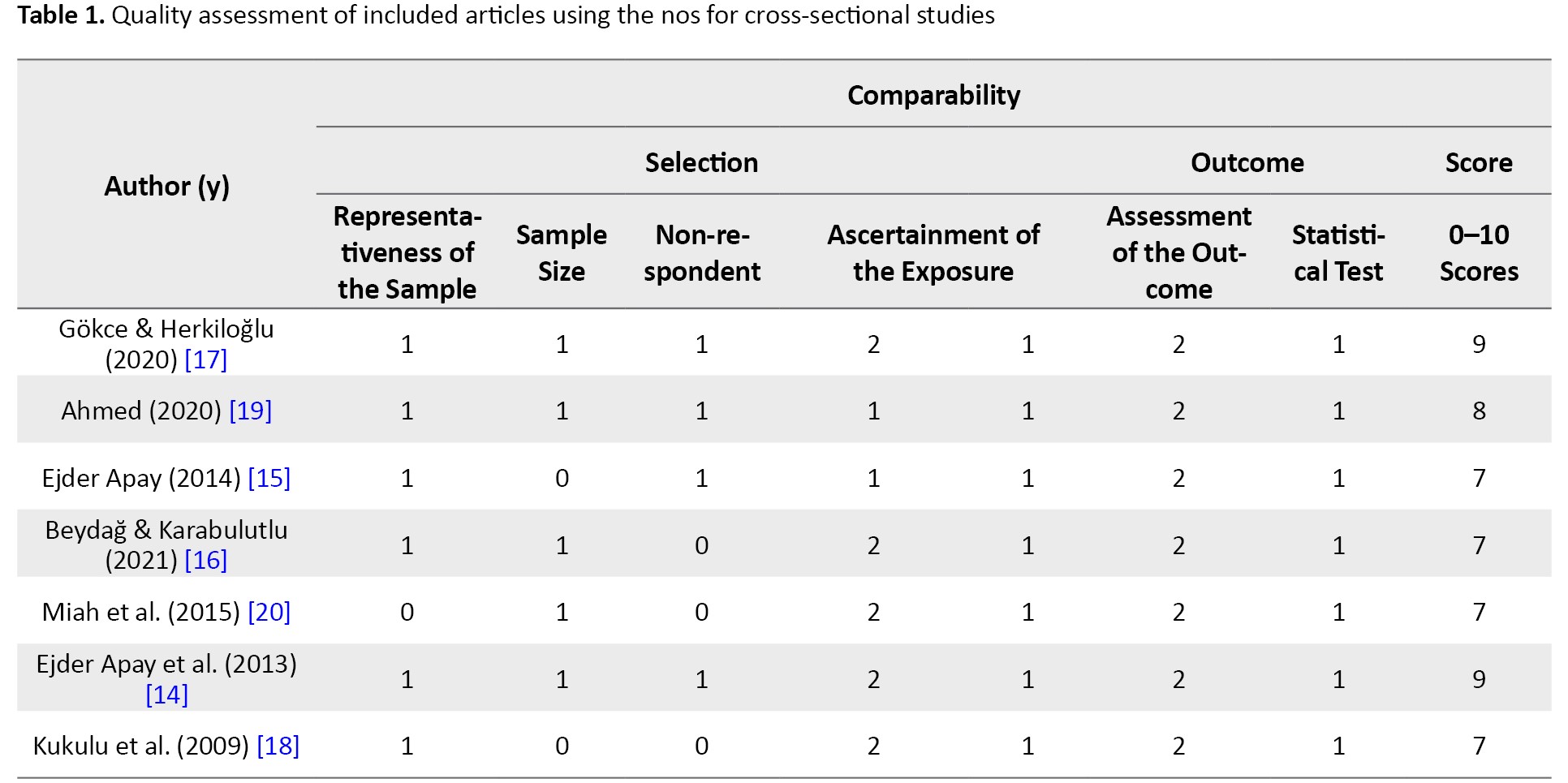

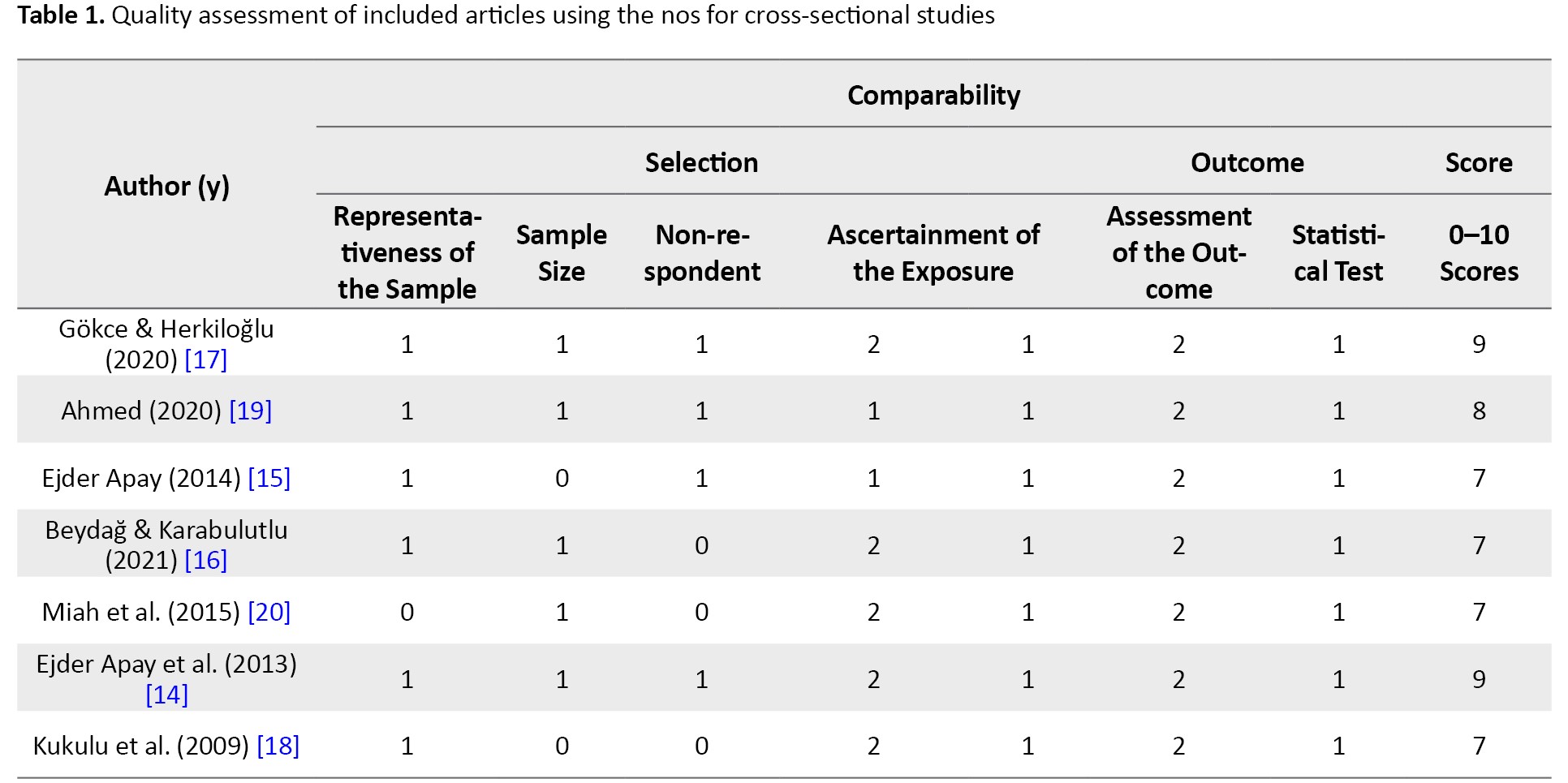

Assessing methodological quality of included articles

The methodological quality assessment of the included articles was carried out using the NOS as one of the most known scales for measuring the quality and risk of bias (ROB) in observational studies [11, 12]. The quality assessments were practiced by two members of the research team Faezeh Habibnejad & Marzieh Azizi independently. The NOS was thus used for evaluating the cross-sectional, case-control, and cohort studies based on three quality parameters (viz. selection, comparability and outcome), divided into 8 specific items, slightly differing when scoring the studies. Each item on the scale was at 1 point, except for the comparability parameter, which was scored up to 2 points. Thus, the maximum score for each article was 9 and those with fewer than 5 points were identified as having a high ROB [13]. In total, 11 studies were examined, and 4 articles were excluded due to their low quality (the score was <5). The details of this scale and its scoring process are illustrated in Table 1.

Summarizing evidence and interpreting findings

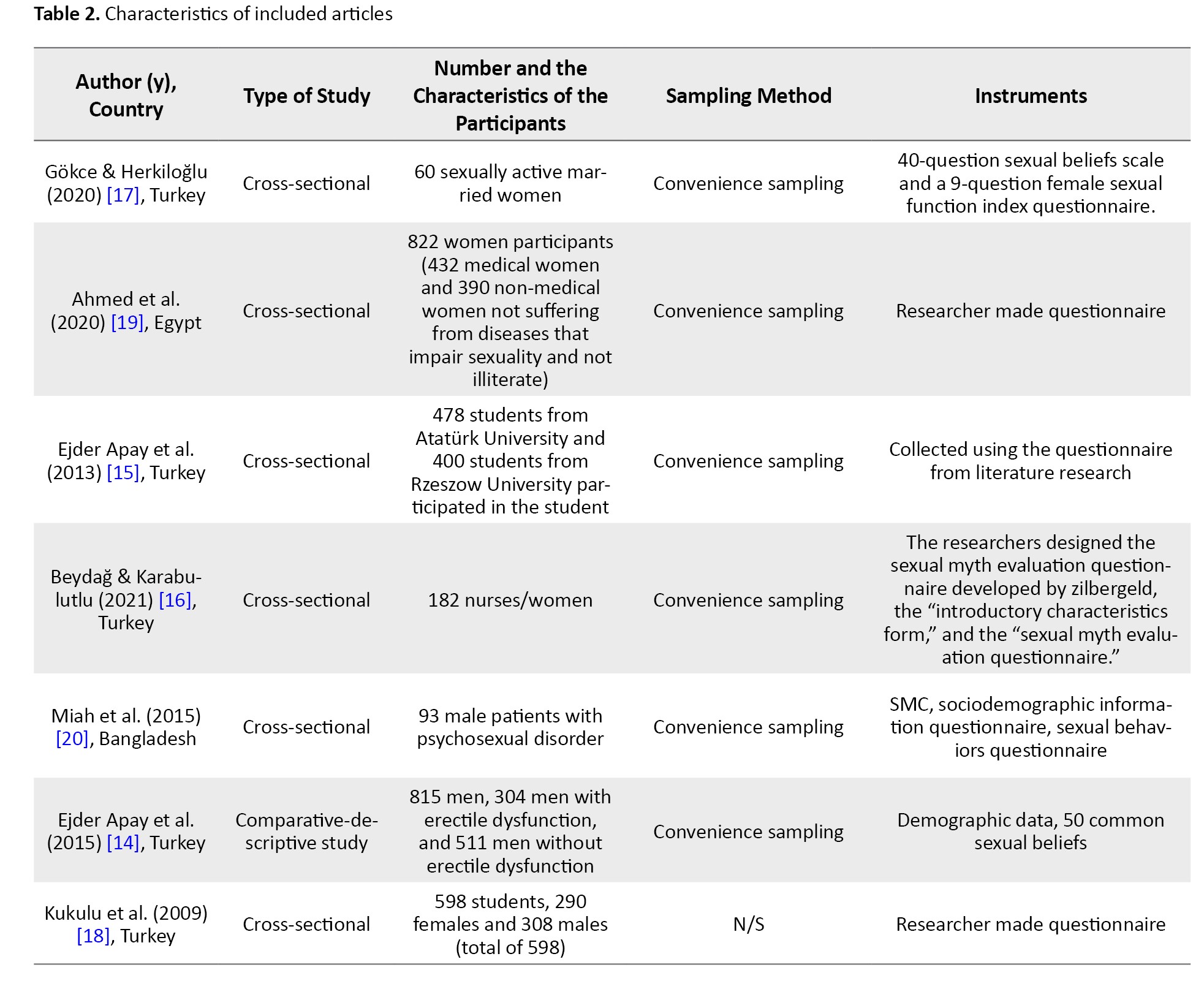

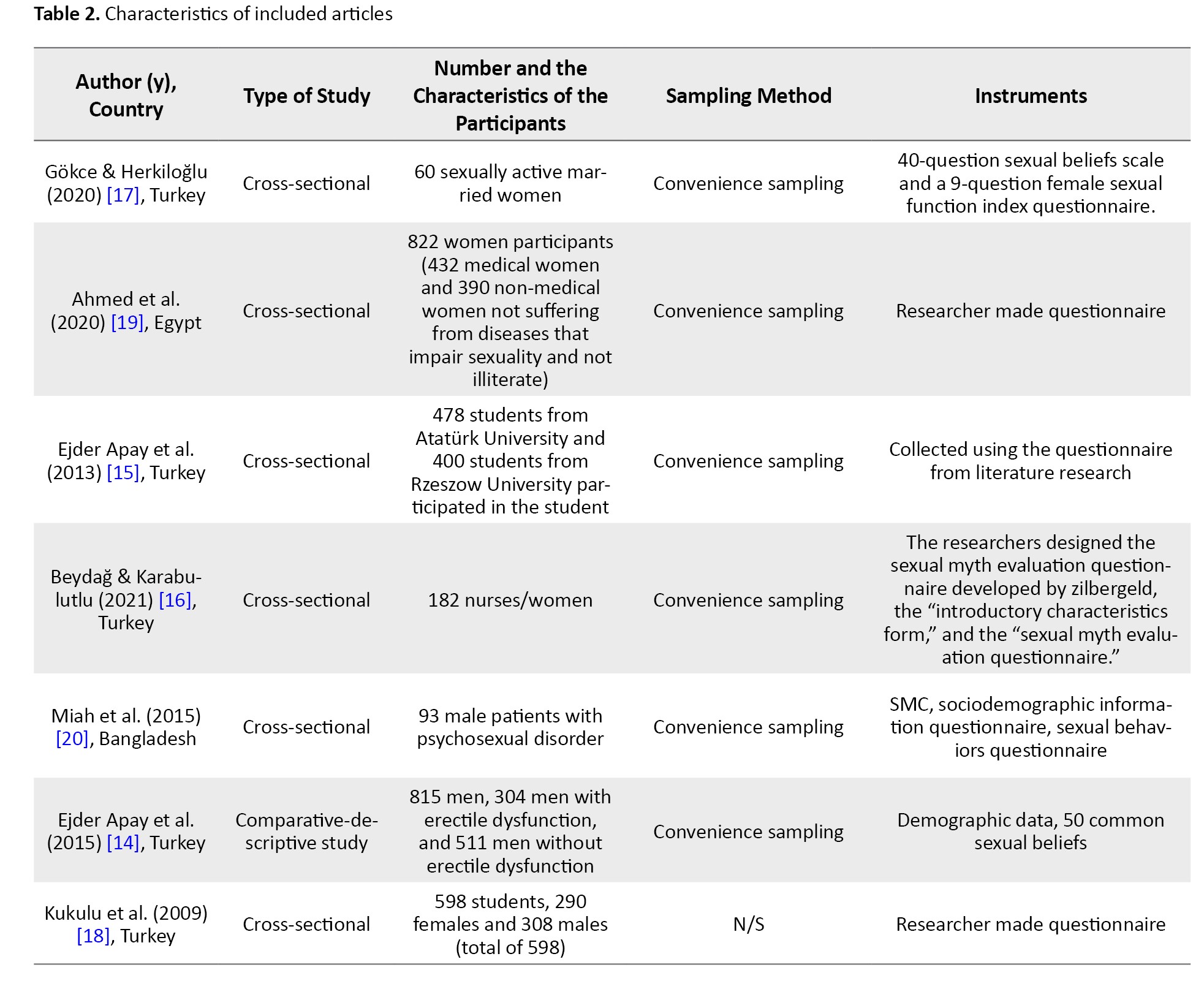

The full texts of the selected articles were thoroughly read and the required information was extracted into descriptive tables and cross-checked by one of the researchers Faezeh Habibnejad Two researchers conducted the investigation independently to avoid ROB and the results were assessed by a third researcher (Soghra Khani) in case of any disagreements. The data, including the first author, year of publication, country of origin, type of study, number and characteristics of participants, sampling method, and instruments, were then obtained (Table 2).

Regarding the validity and reliability of the questionnaire, in 4 articles, the writer made the questionnaire based on literature reviews. A questionnaire form prepared by researchers was used to collect the study data. The data were assessed by calculating the percentages and performing the chi-square test. All analyses set the significance level at P<0.05 [14-19]. The researchers designed the sexual myth evaluation form questionnaire developed by Zilbergeld. The first part consisted of questions about sociodemographic characteristics and sexual history. The second part of the sexual myth evaluation form consisted of 30 sexual myths that were previously used in our country to investigate sexual myths. Statistical analyses were done using SPSS, software, version 21. For categorical variables, the chi-square test and if an expected value was <5, the Fisher exact chi-square test, and the comparison of continuous variables, t-test (in independent groups) were used. Statistical significance was taken as P<0.05 [16]. The Cronbach alpha coefficient of the 40-question sexual beliefs scale was found to be 0.91 and the test re-test reliability coefficient was 0.814. Eight factors comprising 28 items, explaining 65% of total variability, were obtained in the factor analysis done with varimax rotation to construct validity.

The correlation between continuous variables was tested using the female sexual function index questionnaire and the Spearman correlation analysis. The results were evaluated within the 95% confidence interval (CI), and P<0.05 were considered significant [17]. The sociodemographic information questionnaire was used to collect personal and demographic information such as age, sex, education, occupation, residence and marital status of the participants. The test re-test reliability of the sex myths checklist (SMC) is 0.70, which is highly significant at 0.50. The face validity of the checklist appears to be fairly high. The content validity is adequately assured. The sexual behaviors questionnaire consists of a structured questionnaire regarding sexual behavior, and the items were based on a literature survey and clinical experience [20].

Results

Selecting articles

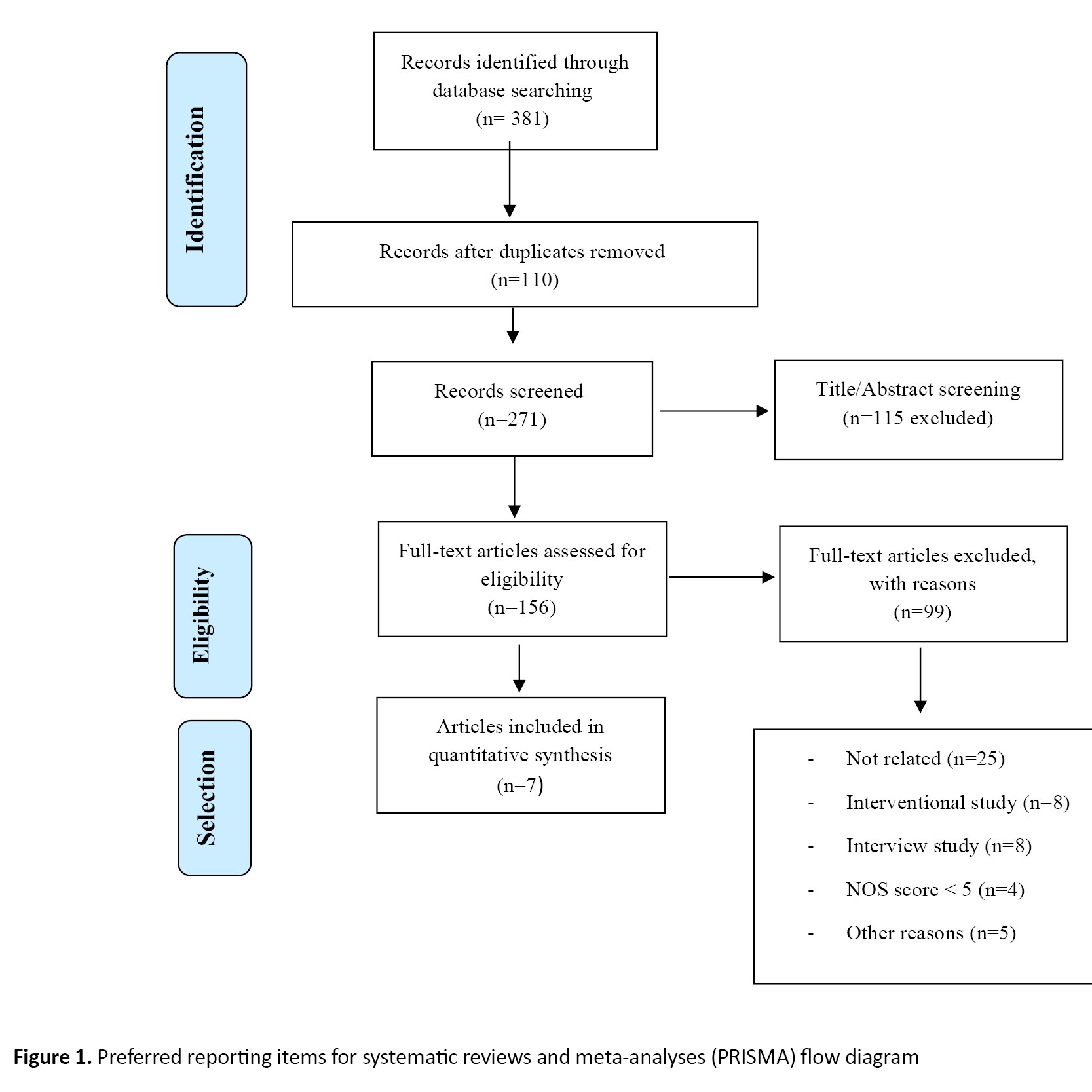

The search on the databases resulted in 381 articles. After excluding the duplicates (n=110), 271 studies remained. Table 2 summarizes the articles selected for data analysis based on their full-text appraisal. Screening the titles and abstracts also led to the exclusion of 115 studies. After a full-text appraisal of the articles assessing sexual myths, 99 full-text studies were removed for not being related (n=25), having interventional designs (n=8), using qualitative analyses (n=8), obtaining the Newcastle-ottawa scale (NOS) score <5 (n=4) and other reasons (e.g. other sexual orientations except for heterosexuality) (n=5). Finally, 7 articles remained in this systematic review (Figure 1).

Characteristics of included articles

The main characteristics of the included articles are depicted in Table 2. Of the studies, 5 cases had been conducted in Turkey [14, 18], one study was from Egypt [19] and one article had been published in Bangladesh [20] between 2009 and 2021. Seven studies recruited 2970 males and females from different age groups, occupations and cultures and the sample sizes varied from 60 to 822 individuals. The data collection was fulfilled with questionnaires, e.g. the sexual beliefs scale [17], the female sexual function index [17], self-report questionnaires developed based on previous literature [15, 18, 19], demographic information forms [14, 17, 20], the 50 common sexual beliefs [14], the introductory characteristics form and the sexual myth evaluation form [16], the SMC and a sociodemographic information questionnaire [20]. The participants, namely, women, students, and men, consisted of married nurses, medical and non-medical staff, medical students and husbands, particularly those with and without erectile dysfunction and psychosexual disorder.

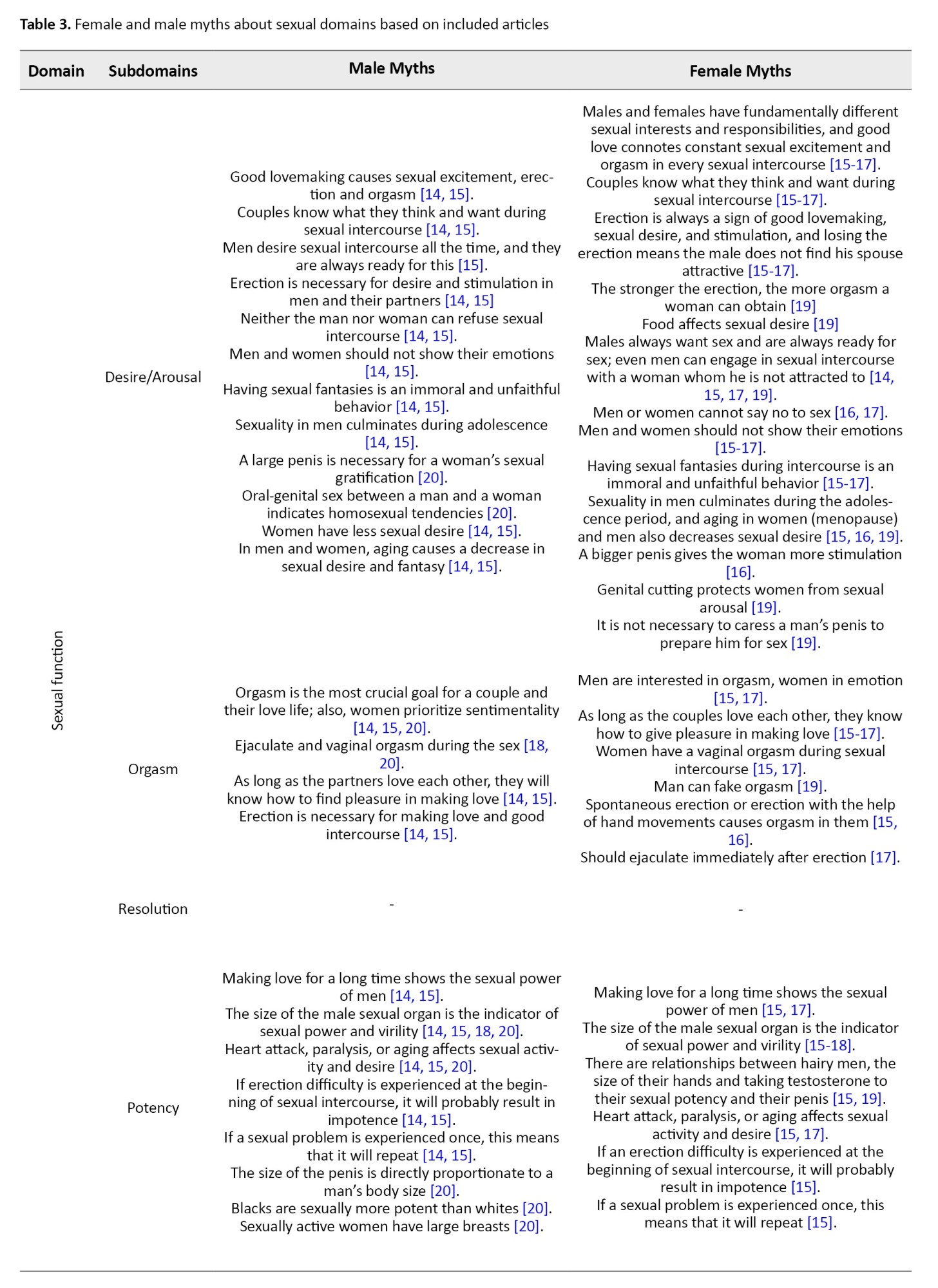

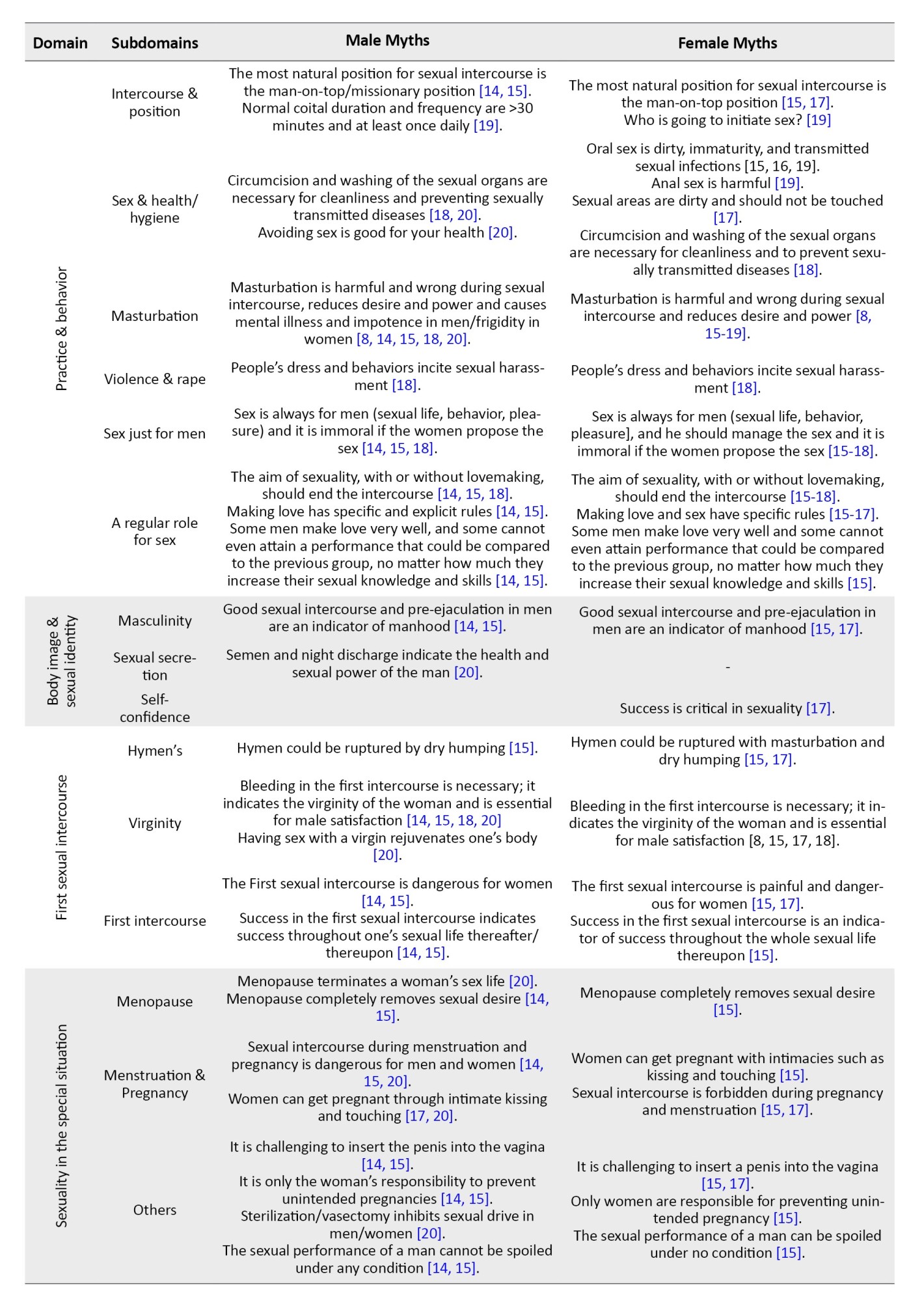

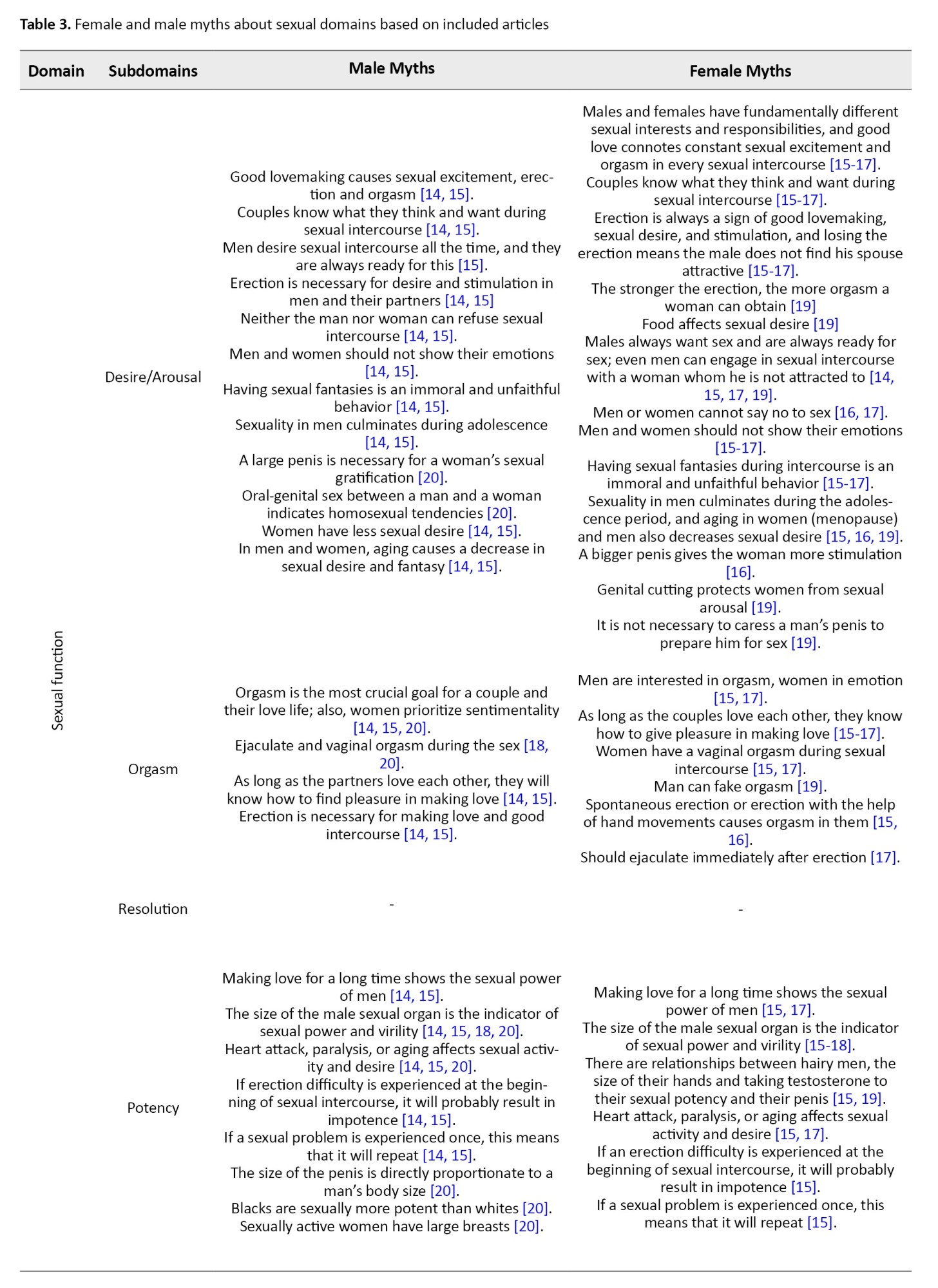

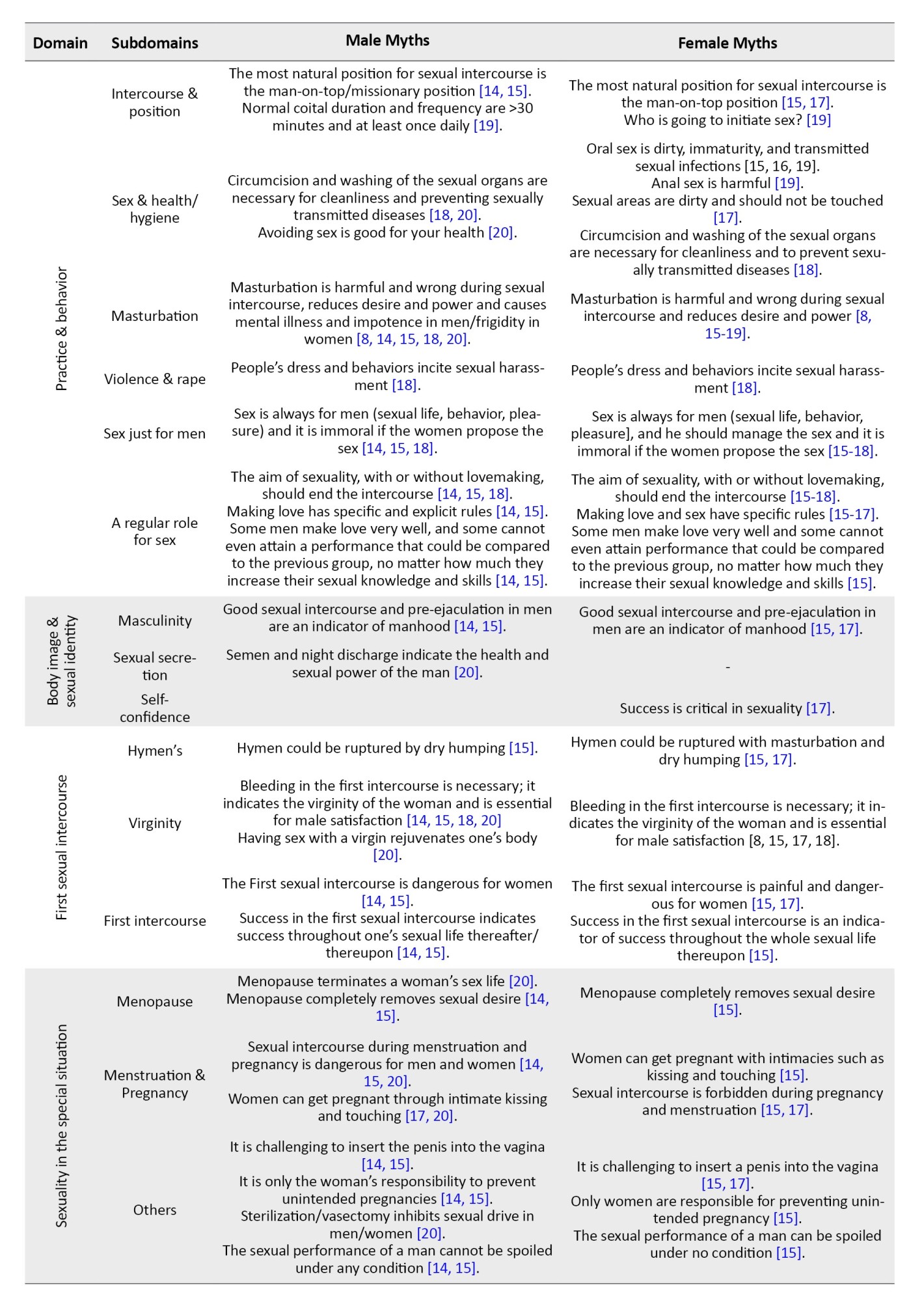

The myths about sexuality were then classified according to their domains and subdomains. The domains consisted of sexual functioning, practice and behavior, body image and sexual identity, first sexual intercourse, and sexuality in special situations. Each domain was also split into the subdomains of desire/arousal, orgasm, resolution and potency (sexual functioning), intercourse and position, sex and health/hygiene, masturbation, violence and rape, sex just for men and regular roles for sex (practice and behavior), masculinity, sexual secretion and self-confidence (body image and sexual identity), hymen, virginity and first sexual intercourse (first sexual intercourse), and menopause, menstruation and pregnancy and others (sexuality in special situations) (Table 3).

Sexual myths

The sexual myths were grouped into five main domains.

Sexual functioning

Sexual functioning was associated with reproduction, which could improve caring and affective bonds between individuals and ultimately bring pleasure. According to Kaplan [23], sexual functioning could be categorized into desire/arousal, orgasm, and resolution [21, 22]. The myths under the subdomain of desire/arousal, orgasm and resolution are listed in Table 3.

In the words of Pamela and Berscheid [24], sexual desire was “a psychological state subjectively experienced by the individual as an awareness that he or she wants or wishes to attain a presumably pleasurable sexual goal that is currently unattainable” [24]. Sexual arousal was also characterized as “an emotional/motivational state that internal and external stimuli can evoke, and that can be inferred from central (verbal), peripheral (genital), and behavioral (action tendencies and motor preparation) responses” [25]. Some myths concerning desire/arousal in males were extracted in this line, such as good lovemaking causes sexual excitement, erection, and orgasm [14, 15] or couples know what they think and want during sexual intercourse [14, 15]. Further myths raised by men are presented in Table 3. There were similarly some myths among women in the subdomain of desire/arousal, e.g. males and females have fundamentally different sexual interests and responsibilities, or good lovemaking connotes constant sexual excitement and orgasm in each sexual intercourse [15, 17]. Besides, an erection is always a sign of good lovemaking as well as sexual desire and stimulation, or losing an erection means men do not find their partners attractive [15, 17]. Other female myths are shown in Table 3. An orgasm was also defined strictly by the muscular contractions involved during sexual activity, along with the characteristic patterns of change in heart rate, blood pressure, respiration rate and volume, which could usually happen when couples reached the height of sexual arousal [26]. There were sexual myths regarding orgasm in males, eg, orgasm is the most crucial goal for a couple, and their love life, or women prioritize sentimentality [14, 15, 20], ejaculation, and vaginal orgasm during sex [18, 20]. Likewise, men are interested in orgasms, women like emotions [15, 17] and men can fake orgasms, which were among the sexual myths in females [19]. Other myths regarding orgasm among women and men are presented in Table 3. Furthermore, resolution was another subdomain described as “the body slowly returning to its normal functioning and swells, and erected body parts return to their previous size and color” [26]. There were no myths in this subdomain. Moreover, the myths about potency in men and women in this regard are mentioned in Table 3.

Practice and behavior

Human sexual activity could refer to any activity practiced individually or in pairs and groups for producing sexual pleasure, classified as sexual behavior [27]. Sexual behavior represents the behavior that individuals engage in to satisfy their essential and sexual needs. Sometimes, the way people behave sexually could have adverse consequences. Therefore, sexual behavior could interfere directly with sexual health. Sexual practice and behavior were thus classified into the subdomains of intercourse and position, sex and health/hygiene, masturbation, violence and rape, sex just for men and regular roles for sex. There were also some myths about intercourse and position in men, .eg. the most natural position for sexual intercourse is the man-on-top/missionary position [14, 15]. The female myths were that the most natural position for sexual intercourse was the man-on-top position [15, 18], which was supposed to allude to sexual intercourse [19]. The male and female myths in the sex and health/hygiene subdomain were circumcision and washing the sexual organs are necessary for cleanliness and preventing sexually transmitted diseases [18, 20]. The rest of the myths in other subdomains are shown in Table 3.

body image and sexual identity

As a complex and multidimensional concept, body image encompasses individuals’ perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors [28]. The relationship between body image, self-image and sexual behavior could accordingly determine the effect of body image on personal and gender-related variables [29]. Body image, sexual identity, sexual well-being, and gender could thus interact in multifaceted ways, and gender dysphoria could negatively affect body image [30]. In addition, body image and sexual identity could be divided into the subdomains of masculinity, sexual secretion and self-confidence. The myth of masculinity in men and women is that good sexual intercourse and pre-ejaculation in men are indicators of manhood [14, 15, 17]. Sexual secretion, just in male myths, also means that semen and night discharge show health and sexual power in men [20]. The myths regarding self-confidence among females and males are given in Table 3.

First sexual intercourse

This domain was partitioned into three subdomains: hymen, virginity, and first sexual intercourse. There were male and female myths about first sexual intercourse, e.g. the first sexual intercourse is dangerous for women [14, 15, 17], or success in the first sexual intercourse indicates success throughout one’s sexual life thereafter/thereupon [14, 15]. The myths regarding virginity and hymen in females and males are listed in Table 3.

Sexuality in special situations

Some situations in women’s lives were sensitive, thereby affecting their sexual relations. In light of this, wrong beliefs could be typically formed in keeping with sociocultural values. Some situations were menopause, menstruation, pregnancy, and others. For example, in menopause, the myths were that menopause terminates a woman’s sex life [20], or that menopause obliterates sexual desire [14, 15]. Menstruation and pregnancy situations were also divided into male and female categories, which included sexual intercourse during menstruation and pregnancy is dangerous for men and women [14, 15, 17, 20] or women can get pregnant through intimate kissing and touching [15, 17, 20]. Other myths are shown in Table 3.

Discussion

The present study focused on female and male myths about sexuality according to the existing literature. Sexual myths can be harmful and perpetuate negative stereotypes. They can lead to misunderstandings, shame, and even unsafe sexual practices. Sexual myths are usually exaggerated and erroneous beliefs of individuals about sexuality and have no scientific value. These erroneous beliefs and concepts affect the attitudes and behaviors of individuals toward sexuality. The belief in sexual legends that exist between males and females is held, but the truth behind these legends will differ based on gender. The deficiency and immorality in society can be observed in individuals of both genders [29, 30]. Sexuality is a phenomenon that varies from person to person and is very variably influenced by cultural and religious factors. Dysfunctional beliefs and myths are universal, found in many cultures, and involve similar themes [16]. Factors such as younger women, homemakers, low level of education, less educated mothers, less educated husbands, merchant husbands, living in a village or city, living in a nuclear family, having an arranged marriage, believing that virginity must be protected until marriage, which affected on sexual beliefs on men and women [26-29]. Therefore, Insufficient education, in particular no access to appropriate sexual information, was likely to maintain all myths and misconceptions in this regard, as pointed out by HCPs. The individuals holding these beliefs or those unprepared to counteract them might thus deter patients with sexual health problems from seeking care [31]. Additionally, there are significant variances among societies regarding sexual beliefs and myths. Healthcare authorities should thus work to enhance societal perceptions because some myths may be commonly held in some groups, but they may not exist in others [32].

Sexual myths cause guilt and feelings of inadequacy and may be the basis for sexual function disorders in husband and wife. Sexual myths influenced the sexual quality of life and marital satisfaction. Sexual myths and misinformation about sexuality can lead to sexual dysfunction in both men and women. As the number of sexual myths held by women increases, sexual desire, arousal, lubrication, pain and overall sexual function worsen [33]. Rates of belief in sexual myths are very high, and sexual myths can cause people to experience unnecessary anxiety both in terms of general sexual health and during sex. They can reduce the level of health and satisfaction of sexual relationships [17]. Therefore, in the above review, sexual myths were divided into 5 domains such as sexual functioning, practice and behavior, body image and sexual identity, first sexual intercourse, and sexuality in special situations. To take appropriate solutions according to the knowledge of the factors affecting sexual belief and health.

Sexuality is generally considered taboo in some cultures, and it is suppressed for reasons other than reproduction. Besides, premarital sex is entirely forbidden. Young adults unfortunately encounter insufficient sex education, and cross-sex friendship is not valued. As a result, the youth frequently receive inaccurate information or hearsay news reports [16], affecting their sexual health. Identifying this problem and providing services by healthcare systems can accordingly contribute to sexual health in the general population [34, 35].

In this review study, sexual myths were categorized into subdomains. There were some myths that men desire sexual intercourse all the time. They are always ready to do so [15], having sexual fantasies is an immoral and unfaithful behavior [14, 15], sexuality in men culminates during adolescence and aging in women (mainly menopause) and men decrease sexual desire [15, 16, 19], oral-genital sex indicates homosexual tendencies [20] and other myths, as mentioned in Table 3. Suppose HCPs and the general population become aware of these sexual beliefs and get informed about the additional ones. In that case, they can more successfully address the related dysfunctions and issues [31].

In this line, Ahmed et al. reported that sexual myths could have many consequences, affecting sexual and public health. Some sexual beliefs have also been explored. In this study, the participants were women from medical and non-medical groups. The results showed that the participants had many misunderstandings. They had further uncovered some sexual myths among physicians. Besides, rural women had more misconceptions than urban ones. At the same time, education could shape sexual myths in women, so higher education meant fewer myths [19]. The data in the present study were categorized similarly to the abovementioned work. Many people still believe in these myths, especially older adults, due to the ideology born with them and grew up with them over the years, then transferred to their children and later generations.

In another study, Beydağ Karabulutlu reflected on the community of nurses as part of the healthcare system and found some erroneous beliefs about sex. Although the study results could not be generalized to the entire society, the importance of education has been highlighted. It was thus vital to devote much more attention to sex education curricula in these groups as they were in charge of health education in each society, and such beliefs were currently being observed in this community and the general population [16]. Since sexual HCPs could play a prominent role in increasing women’s sexual satisfaction, they could help improve the quality of their sexual life by identifying and discussing ways to control it. Enhancing information and eliminating misunderstandings in this group was generally adequate for public health [19].

According to Gökce and Herkiloğlu, a high percentage of sexual myths were occurring among sexually active married women. These myths could induce unnecessary anxiety and diminish sexual health and pleasure [17]. On the contrary, Kilci reported that sexual experience could reduce myths about sexuality [32]. They stated that women with sexual experience could hold fewer sexual misconceptions. Yasan et al. had comparably found that myths were less prevalent among women having sexual partners, although such myths seemed to decline slightly with sexual experience. Most myths, however, could persist despite sexual experiences [36].

Inaccuracies in sexual ideas underlying male sexual dysfunction included emphasizing overly high sexual performance. Accordingly, Ejder-Apay et al. revealed that men with erectile dysfunction had endorsed 8 beliefs about sexual activity more frequently than those without this disorder. These findings indicated an association between specific cognitions and erectile dysfunctions. Most cognitions were concerned with high expectations of male sexual functioning [15]. Some surveys have even shown that such myths were frequently believed to be true [32, 37, 38]. Karabulutlu and Yilmaz further reported that the most common myths were “as long as the couples love each other, they know how to give pleasure in making love” (80%), “sex is good only with a simultaneous orgasm” (75%) and “erection is always a sign of desire” (65%). Ejder-Apay et al. also found that “as long as the couples love each other, they know how to give pleasure in making love” (76.2%), “couples instinctively know the feelings and thinking of each other” (69.9%) and “men are always passionate and ready for sexual intercourse” (65.9%). Contrary to the present study, these myths were assumed to be wrong sexual beliefs [39]. Our findings supported the necessity of additional training addressing sexual myths and Notably, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, no review studies have been conducted thus far on this subject as the main strength. However, there were some limitations wherein sexual myths among women and men with heterosexual orientations were merely taken into account. Still, there was no care for other sexual orientations, e.g. lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender. It was thus suggested to investigate myths in other sexual orientations in future surveys. This study also had database, gray literature and publication biases.

Conclusion

As a whole, sexual myths could spread from generation to generation through word-of-mouth due to the rise in erroneous ideas and exaggerated discourses in society. The study findings accordingly demonstrated that readers could learn incorrect views and their various aspects.

Recommendations

According to the study findings, it is a good idea to start sex education in middle school, incorporating it into regular formal curricula and taught by HCPs with specialized knowledge in this area. Families should also become aware of sex education and sexual health clinics and counseling centers should be established where the required information is provided in this respect. Before providing holistic care without ignoring the sexual aspect of humans, HCPs who are mainly concerned with humans and fulfill their caregiving duties must thus first acknowledge themselves and be conscious of their incorrect information. In this line, young people, especially the would-be HCPs, should attend courses on sexuality, gender-related issues and sexual and reproductive health.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The authors entirely respected the ethical considerations and general standards for publication in terms of plagiarism, misconduct, data fabrication and/or falsification, double publication and/or submission, redundancy, and so forth.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

conceptualization and study designing: Soghra Khani; Data collection: Faezeh Habibnejad Roushan, Farangis Habibi and Marzieh Azizi; Data analysis and interpretation: Faezeh Habibnejad Roushan; drafting the manuscript: Faezeh Habibnejad Roushan and Marzieh Azizi; revising the manuscript: Soghra Khani and Marzieh Azizi.

Conflict of interest

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection and analysis, interpretation of the results, and drafting of the manuscript. Each author approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

References

Individuals’ beliefs about sexuality are every so often established on a series of exaggerated, incorrect and unscientific concepts, symbols and emotions, such as a sense of guilt, feelings of inadequacy, anxiety, and even fear of failure regarding some sexual issues they deem to be true. These erroneous beliefs and concepts can affect mindsets and behaviors about male and female sexuality [1]. Sexual myths are also determined by various factors, including personal beliefs, attitudes and values about sex, which are fundamentally shaped by the surrounding cultures [2]. Given that, sexual beliefs are typically impacted by cultural background, educational and social influence, as well as personal experience [3]. Sexuality is currently forbidden in some Asian nations, including China, wherein sex education in schools has been historically limited, so it has been, to date, ignored by women and not taken seriously by healthcare providers (HCPs) [4].

At present, the healthcare system in Iran does not meet women’s sexual needs [5]. Notably, there are myths about sexuality altering sexual satisfaction, encompassing personal and relational components, which include the perceived compatibility of sexual desire and beliefs, values, and attitudes. The effect of sexual myths and awareness of sexual desires on the marital satisfaction of couples has been proven. Sexual compatibility in marriage is an integral part of the marital process and significantly affects the satisfaction of the marriage and the marital relationship. Although the absence of sexual function problems has a positive impact on marriage, it is argued that the experience of these problems negatively affects marriage, undermining positive feelings and marital intimacy [6, 7, 8, 9, 10]. From this perspective, there is a need to investigate sexual and reproductive health needs in different societies and cultural contexts, demanding counseling centers promoting women’s sexual and reproductive healthcare services, given the high frequency of women being referred to medical facilities to deal with sexual problems. If HCPs know partly about sexual myths, they can help treat sexual and reproductive disorders in the early stages [5]. Thus, the Iranian Ministry of Health and Medical Education has recently created sexual health clinics affiliated with the universities of medical sciences. Reflection on the related literature reveals no review study assessing myths about female and male sexuality, to the best of the author’s knowledge. As wrong sexual myths can have adverse effects on couples’ sexual health, this review study aimed to fill this gap and review the most common myths around sexuality among women and men.

Materials and Methods

This systematic review of the existing literature on female and male myths about sexuality was fulfilled in five steps: Addressing the research question, searching and retrieving the relevant articles, assessing the methodological quality of the included studies, summarizing the evidence and results, and interpreting and discussing the findings, delineated as follows. The research question was then developed based on the PECO components, viz. population (P) (the type of participants), exposure (E) (sexual myths), comparator (C) (not applicable) and outcome (the dependent variable).

Addressing research question

Initially, the main research question in this study was addressed as follows: What are the female and male myths about sexuality?

Searching and retrieving relevant articles

Two researchers Faezeh Habibnejad & Marzieh Azizi independently conducted an online search on the databases of PubMed, Google Scholar, Magiran, Scopus, PsycINFO, IranDoc, Ovid, ProQuest, Scientific Information Database (SID) and the Cochrane Library. The search process commenced on December 3 and ended on December 21, 2022. The search was done in Persian and English. The medical subject heading (MeSH) was also utilized to find the related keywords, viz., “sexual myth,” “sexual beliefs,” “wrong beliefs” and “dysfunctional sexual beliefs.” The search process was mainly based on systematic search, using the following keywords: (“Sexual myth” [title/abstract]) OR (“sexual beliefs” [title/abstract]) “dysfunctional sexual beliefs” [title/abstract], (“sexual myths” [title/abstract]) OR (“sexual beliefs” [title/abstract]) AND [(“wrong beliefs”)) OR (“incorrect beliefs”)], [“sexual myths” “sexual beliefs” (title/abstract)]. The articles were then reviewed and the most relevant ones meeting the inclusion criteria were selected.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Two researchers Faezeh Habibnejad & Marzieh Azizi independently screened the article titles and abstracts. If a study was relevant, the full-text manuscript was reviewed for further assessments according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The search was conducted in Persian and English, and studies in other languages were not included. The cross-sectional studies that reported myths about sexuality, as well as those with no year of publication limitation, were also included. Some articles were eliminated for no access to their full texts, recruiting interventional designs, doing qualitative analysis, having the NOS score <5 and so on.

Assessing methodological quality of included articles

The methodological quality assessment of the included articles was carried out using the NOS as one of the most known scales for measuring the quality and risk of bias (ROB) in observational studies [11, 12]. The quality assessments were practiced by two members of the research team Faezeh Habibnejad & Marzieh Azizi independently. The NOS was thus used for evaluating the cross-sectional, case-control, and cohort studies based on three quality parameters (viz. selection, comparability and outcome), divided into 8 specific items, slightly differing when scoring the studies. Each item on the scale was at 1 point, except for the comparability parameter, which was scored up to 2 points. Thus, the maximum score for each article was 9 and those with fewer than 5 points were identified as having a high ROB [13]. In total, 11 studies were examined, and 4 articles were excluded due to their low quality (the score was <5). The details of this scale and its scoring process are illustrated in Table 1.

Summarizing evidence and interpreting findings

The full texts of the selected articles were thoroughly read and the required information was extracted into descriptive tables and cross-checked by one of the researchers Faezeh Habibnejad Two researchers conducted the investigation independently to avoid ROB and the results were assessed by a third researcher (Soghra Khani) in case of any disagreements. The data, including the first author, year of publication, country of origin, type of study, number and characteristics of participants, sampling method, and instruments, were then obtained (Table 2).

Regarding the validity and reliability of the questionnaire, in 4 articles, the writer made the questionnaire based on literature reviews. A questionnaire form prepared by researchers was used to collect the study data. The data were assessed by calculating the percentages and performing the chi-square test. All analyses set the significance level at P<0.05 [14-19]. The researchers designed the sexual myth evaluation form questionnaire developed by Zilbergeld. The first part consisted of questions about sociodemographic characteristics and sexual history. The second part of the sexual myth evaluation form consisted of 30 sexual myths that were previously used in our country to investigate sexual myths. Statistical analyses were done using SPSS, software, version 21. For categorical variables, the chi-square test and if an expected value was <5, the Fisher exact chi-square test, and the comparison of continuous variables, t-test (in independent groups) were used. Statistical significance was taken as P<0.05 [16]. The Cronbach alpha coefficient of the 40-question sexual beliefs scale was found to be 0.91 and the test re-test reliability coefficient was 0.814. Eight factors comprising 28 items, explaining 65% of total variability, were obtained in the factor analysis done with varimax rotation to construct validity.

The correlation between continuous variables was tested using the female sexual function index questionnaire and the Spearman correlation analysis. The results were evaluated within the 95% confidence interval (CI), and P<0.05 were considered significant [17]. The sociodemographic information questionnaire was used to collect personal and demographic information such as age, sex, education, occupation, residence and marital status of the participants. The test re-test reliability of the sex myths checklist (SMC) is 0.70, which is highly significant at 0.50. The face validity of the checklist appears to be fairly high. The content validity is adequately assured. The sexual behaviors questionnaire consists of a structured questionnaire regarding sexual behavior, and the items were based on a literature survey and clinical experience [20].

Results

Selecting articles

The search on the databases resulted in 381 articles. After excluding the duplicates (n=110), 271 studies remained. Table 2 summarizes the articles selected for data analysis based on their full-text appraisal. Screening the titles and abstracts also led to the exclusion of 115 studies. After a full-text appraisal of the articles assessing sexual myths, 99 full-text studies were removed for not being related (n=25), having interventional designs (n=8), using qualitative analyses (n=8), obtaining the Newcastle-ottawa scale (NOS) score <5 (n=4) and other reasons (e.g. other sexual orientations except for heterosexuality) (n=5). Finally, 7 articles remained in this systematic review (Figure 1).

Characteristics of included articles

The main characteristics of the included articles are depicted in Table 2. Of the studies, 5 cases had been conducted in Turkey [14, 18], one study was from Egypt [19] and one article had been published in Bangladesh [20] between 2009 and 2021. Seven studies recruited 2970 males and females from different age groups, occupations and cultures and the sample sizes varied from 60 to 822 individuals. The data collection was fulfilled with questionnaires, e.g. the sexual beliefs scale [17], the female sexual function index [17], self-report questionnaires developed based on previous literature [15, 18, 19], demographic information forms [14, 17, 20], the 50 common sexual beliefs [14], the introductory characteristics form and the sexual myth evaluation form [16], the SMC and a sociodemographic information questionnaire [20]. The participants, namely, women, students, and men, consisted of married nurses, medical and non-medical staff, medical students and husbands, particularly those with and without erectile dysfunction and psychosexual disorder.

The myths about sexuality were then classified according to their domains and subdomains. The domains consisted of sexual functioning, practice and behavior, body image and sexual identity, first sexual intercourse, and sexuality in special situations. Each domain was also split into the subdomains of desire/arousal, orgasm, resolution and potency (sexual functioning), intercourse and position, sex and health/hygiene, masturbation, violence and rape, sex just for men and regular roles for sex (practice and behavior), masculinity, sexual secretion and self-confidence (body image and sexual identity), hymen, virginity and first sexual intercourse (first sexual intercourse), and menopause, menstruation and pregnancy and others (sexuality in special situations) (Table 3).

Sexual myths

The sexual myths were grouped into five main domains.

Sexual functioning

Sexual functioning was associated with reproduction, which could improve caring and affective bonds between individuals and ultimately bring pleasure. According to Kaplan [23], sexual functioning could be categorized into desire/arousal, orgasm, and resolution [21, 22]. The myths under the subdomain of desire/arousal, orgasm and resolution are listed in Table 3.

In the words of Pamela and Berscheid [24], sexual desire was “a psychological state subjectively experienced by the individual as an awareness that he or she wants or wishes to attain a presumably pleasurable sexual goal that is currently unattainable” [24]. Sexual arousal was also characterized as “an emotional/motivational state that internal and external stimuli can evoke, and that can be inferred from central (verbal), peripheral (genital), and behavioral (action tendencies and motor preparation) responses” [25]. Some myths concerning desire/arousal in males were extracted in this line, such as good lovemaking causes sexual excitement, erection, and orgasm [14, 15] or couples know what they think and want during sexual intercourse [14, 15]. Further myths raised by men are presented in Table 3. There were similarly some myths among women in the subdomain of desire/arousal, e.g. males and females have fundamentally different sexual interests and responsibilities, or good lovemaking connotes constant sexual excitement and orgasm in each sexual intercourse [15, 17]. Besides, an erection is always a sign of good lovemaking as well as sexual desire and stimulation, or losing an erection means men do not find their partners attractive [15, 17]. Other female myths are shown in Table 3. An orgasm was also defined strictly by the muscular contractions involved during sexual activity, along with the characteristic patterns of change in heart rate, blood pressure, respiration rate and volume, which could usually happen when couples reached the height of sexual arousal [26]. There were sexual myths regarding orgasm in males, eg, orgasm is the most crucial goal for a couple, and their love life, or women prioritize sentimentality [14, 15, 20], ejaculation, and vaginal orgasm during sex [18, 20]. Likewise, men are interested in orgasms, women like emotions [15, 17] and men can fake orgasms, which were among the sexual myths in females [19]. Other myths regarding orgasm among women and men are presented in Table 3. Furthermore, resolution was another subdomain described as “the body slowly returning to its normal functioning and swells, and erected body parts return to their previous size and color” [26]. There were no myths in this subdomain. Moreover, the myths about potency in men and women in this regard are mentioned in Table 3.

Practice and behavior

Human sexual activity could refer to any activity practiced individually or in pairs and groups for producing sexual pleasure, classified as sexual behavior [27]. Sexual behavior represents the behavior that individuals engage in to satisfy their essential and sexual needs. Sometimes, the way people behave sexually could have adverse consequences. Therefore, sexual behavior could interfere directly with sexual health. Sexual practice and behavior were thus classified into the subdomains of intercourse and position, sex and health/hygiene, masturbation, violence and rape, sex just for men and regular roles for sex. There were also some myths about intercourse and position in men, .eg. the most natural position for sexual intercourse is the man-on-top/missionary position [14, 15]. The female myths were that the most natural position for sexual intercourse was the man-on-top position [15, 18], which was supposed to allude to sexual intercourse [19]. The male and female myths in the sex and health/hygiene subdomain were circumcision and washing the sexual organs are necessary for cleanliness and preventing sexually transmitted diseases [18, 20]. The rest of the myths in other subdomains are shown in Table 3.

body image and sexual identity

As a complex and multidimensional concept, body image encompasses individuals’ perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors [28]. The relationship between body image, self-image and sexual behavior could accordingly determine the effect of body image on personal and gender-related variables [29]. Body image, sexual identity, sexual well-being, and gender could thus interact in multifaceted ways, and gender dysphoria could negatively affect body image [30]. In addition, body image and sexual identity could be divided into the subdomains of masculinity, sexual secretion and self-confidence. The myth of masculinity in men and women is that good sexual intercourse and pre-ejaculation in men are indicators of manhood [14, 15, 17]. Sexual secretion, just in male myths, also means that semen and night discharge show health and sexual power in men [20]. The myths regarding self-confidence among females and males are given in Table 3.

First sexual intercourse

This domain was partitioned into three subdomains: hymen, virginity, and first sexual intercourse. There were male and female myths about first sexual intercourse, e.g. the first sexual intercourse is dangerous for women [14, 15, 17], or success in the first sexual intercourse indicates success throughout one’s sexual life thereafter/thereupon [14, 15]. The myths regarding virginity and hymen in females and males are listed in Table 3.

Sexuality in special situations

Some situations in women’s lives were sensitive, thereby affecting their sexual relations. In light of this, wrong beliefs could be typically formed in keeping with sociocultural values. Some situations were menopause, menstruation, pregnancy, and others. For example, in menopause, the myths were that menopause terminates a woman’s sex life [20], or that menopause obliterates sexual desire [14, 15]. Menstruation and pregnancy situations were also divided into male and female categories, which included sexual intercourse during menstruation and pregnancy is dangerous for men and women [14, 15, 17, 20] or women can get pregnant through intimate kissing and touching [15, 17, 20]. Other myths are shown in Table 3.

Discussion

The present study focused on female and male myths about sexuality according to the existing literature. Sexual myths can be harmful and perpetuate negative stereotypes. They can lead to misunderstandings, shame, and even unsafe sexual practices. Sexual myths are usually exaggerated and erroneous beliefs of individuals about sexuality and have no scientific value. These erroneous beliefs and concepts affect the attitudes and behaviors of individuals toward sexuality. The belief in sexual legends that exist between males and females is held, but the truth behind these legends will differ based on gender. The deficiency and immorality in society can be observed in individuals of both genders [29, 30]. Sexuality is a phenomenon that varies from person to person and is very variably influenced by cultural and religious factors. Dysfunctional beliefs and myths are universal, found in many cultures, and involve similar themes [16]. Factors such as younger women, homemakers, low level of education, less educated mothers, less educated husbands, merchant husbands, living in a village or city, living in a nuclear family, having an arranged marriage, believing that virginity must be protected until marriage, which affected on sexual beliefs on men and women [26-29]. Therefore, Insufficient education, in particular no access to appropriate sexual information, was likely to maintain all myths and misconceptions in this regard, as pointed out by HCPs. The individuals holding these beliefs or those unprepared to counteract them might thus deter patients with sexual health problems from seeking care [31]. Additionally, there are significant variances among societies regarding sexual beliefs and myths. Healthcare authorities should thus work to enhance societal perceptions because some myths may be commonly held in some groups, but they may not exist in others [32].

Sexual myths cause guilt and feelings of inadequacy and may be the basis for sexual function disorders in husband and wife. Sexual myths influenced the sexual quality of life and marital satisfaction. Sexual myths and misinformation about sexuality can lead to sexual dysfunction in both men and women. As the number of sexual myths held by women increases, sexual desire, arousal, lubrication, pain and overall sexual function worsen [33]. Rates of belief in sexual myths are very high, and sexual myths can cause people to experience unnecessary anxiety both in terms of general sexual health and during sex. They can reduce the level of health and satisfaction of sexual relationships [17]. Therefore, in the above review, sexual myths were divided into 5 domains such as sexual functioning, practice and behavior, body image and sexual identity, first sexual intercourse, and sexuality in special situations. To take appropriate solutions according to the knowledge of the factors affecting sexual belief and health.

Sexuality is generally considered taboo in some cultures, and it is suppressed for reasons other than reproduction. Besides, premarital sex is entirely forbidden. Young adults unfortunately encounter insufficient sex education, and cross-sex friendship is not valued. As a result, the youth frequently receive inaccurate information or hearsay news reports [16], affecting their sexual health. Identifying this problem and providing services by healthcare systems can accordingly contribute to sexual health in the general population [34, 35].

In this review study, sexual myths were categorized into subdomains. There were some myths that men desire sexual intercourse all the time. They are always ready to do so [15], having sexual fantasies is an immoral and unfaithful behavior [14, 15], sexuality in men culminates during adolescence and aging in women (mainly menopause) and men decrease sexual desire [15, 16, 19], oral-genital sex indicates homosexual tendencies [20] and other myths, as mentioned in Table 3. Suppose HCPs and the general population become aware of these sexual beliefs and get informed about the additional ones. In that case, they can more successfully address the related dysfunctions and issues [31].

In this line, Ahmed et al. reported that sexual myths could have many consequences, affecting sexual and public health. Some sexual beliefs have also been explored. In this study, the participants were women from medical and non-medical groups. The results showed that the participants had many misunderstandings. They had further uncovered some sexual myths among physicians. Besides, rural women had more misconceptions than urban ones. At the same time, education could shape sexual myths in women, so higher education meant fewer myths [19]. The data in the present study were categorized similarly to the abovementioned work. Many people still believe in these myths, especially older adults, due to the ideology born with them and grew up with them over the years, then transferred to their children and later generations.

In another study, Beydağ Karabulutlu reflected on the community of nurses as part of the healthcare system and found some erroneous beliefs about sex. Although the study results could not be generalized to the entire society, the importance of education has been highlighted. It was thus vital to devote much more attention to sex education curricula in these groups as they were in charge of health education in each society, and such beliefs were currently being observed in this community and the general population [16]. Since sexual HCPs could play a prominent role in increasing women’s sexual satisfaction, they could help improve the quality of their sexual life by identifying and discussing ways to control it. Enhancing information and eliminating misunderstandings in this group was generally adequate for public health [19].

According to Gökce and Herkiloğlu, a high percentage of sexual myths were occurring among sexually active married women. These myths could induce unnecessary anxiety and diminish sexual health and pleasure [17]. On the contrary, Kilci reported that sexual experience could reduce myths about sexuality [32]. They stated that women with sexual experience could hold fewer sexual misconceptions. Yasan et al. had comparably found that myths were less prevalent among women having sexual partners, although such myths seemed to decline slightly with sexual experience. Most myths, however, could persist despite sexual experiences [36].

Inaccuracies in sexual ideas underlying male sexual dysfunction included emphasizing overly high sexual performance. Accordingly, Ejder-Apay et al. revealed that men with erectile dysfunction had endorsed 8 beliefs about sexual activity more frequently than those without this disorder. These findings indicated an association between specific cognitions and erectile dysfunctions. Most cognitions were concerned with high expectations of male sexual functioning [15]. Some surveys have even shown that such myths were frequently believed to be true [32, 37, 38]. Karabulutlu and Yilmaz further reported that the most common myths were “as long as the couples love each other, they know how to give pleasure in making love” (80%), “sex is good only with a simultaneous orgasm” (75%) and “erection is always a sign of desire” (65%). Ejder-Apay et al. also found that “as long as the couples love each other, they know how to give pleasure in making love” (76.2%), “couples instinctively know the feelings and thinking of each other” (69.9%) and “men are always passionate and ready for sexual intercourse” (65.9%). Contrary to the present study, these myths were assumed to be wrong sexual beliefs [39]. Our findings supported the necessity of additional training addressing sexual myths and Notably, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, no review studies have been conducted thus far on this subject as the main strength. However, there were some limitations wherein sexual myths among women and men with heterosexual orientations were merely taken into account. Still, there was no care for other sexual orientations, e.g. lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender. It was thus suggested to investigate myths in other sexual orientations in future surveys. This study also had database, gray literature and publication biases.

Conclusion

As a whole, sexual myths could spread from generation to generation through word-of-mouth due to the rise in erroneous ideas and exaggerated discourses in society. The study findings accordingly demonstrated that readers could learn incorrect views and their various aspects.

Recommendations

According to the study findings, it is a good idea to start sex education in middle school, incorporating it into regular formal curricula and taught by HCPs with specialized knowledge in this area. Families should also become aware of sex education and sexual health clinics and counseling centers should be established where the required information is provided in this respect. Before providing holistic care without ignoring the sexual aspect of humans, HCPs who are mainly concerned with humans and fulfill their caregiving duties must thus first acknowledge themselves and be conscious of their incorrect information. In this line, young people, especially the would-be HCPs, should attend courses on sexuality, gender-related issues and sexual and reproductive health.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The authors entirely respected the ethical considerations and general standards for publication in terms of plagiarism, misconduct, data fabrication and/or falsification, double publication and/or submission, redundancy, and so forth.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

conceptualization and study designing: Soghra Khani; Data collection: Faezeh Habibnejad Roushan, Farangis Habibi and Marzieh Azizi; Data analysis and interpretation: Faezeh Habibnejad Roushan; drafting the manuscript: Faezeh Habibnejad Roushan and Marzieh Azizi; revising the manuscript: Soghra Khani and Marzieh Azizi.

Conflict of interest

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection and analysis, interpretation of the results, and drafting of the manuscript. Each author approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

References

- Grzanka PR, Zeiders KH, Miles JR. Beyond “born this way?” Reconsidering sexual orientation beliefs and attitudes. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2016; 63(1):67-75. [DOI:10.1037/cou0000124] [PMID]

- Montemurro B, Bartasavich J, Wintermute L. Let’s (not) talk about sex: The gender of sexual discourse. Sexuality & Culture. 2015; 19:139-56. [DOI:10.1007/s12119-014-9250-5]

- Peixoto MM, Nobre P. Dysfunctional sexual beliefs: A comparative study of heterosexual men and women, gay men, and lesbian women with and without sexual problems. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2014; 11(11):2690-700. [DOI:10.1111/jsm.12666] [PMID]

- Ekşi Z, Kömürcü N. Knowledge level of university students about sexually transmitted diseases. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2014; 122:465-72. [DOI:10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.01.1374]

- Khani S, Moghaddam-Banaem L, Mohamadi E, Vedadhir AA, Hajizadeh E. Women’s sexual and reproductive health care needs assessment: An Iranian perspective. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. 2018; 24(7):637-43. [DOI:10.26719/2018.24.7.637] [PMID]

- Pawłowska A, Loeys T, Janssen E, Dewitte M. The role of dyadic sexual desire similarity in predicting sexual behaviors in cohabitating couples: An ecological momentary assessment study. The Journal of Sex Research. 2024; 61(2):261-73. [DOI:10.1080/00224499.2023.2170965] [PMID]

- Rosen NO, Corsini-Munt S, Dubé JP, Boudreau C, Muise A. Partner responses to low desire: Associations with sexual, relational, and psychological well-being among couples coping with female sexual interest/arousal disorder. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2020; 17(11):2168-80. [DOI:10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.08.015]

- Delatorre MZ, Wagner A. Marital quality assessment: Reviewing the concept, instruments, and methods. Marriage & Family Review. 2020; 56(3):193-216. [DOI:10.1080/01494929.2020.1712300]

- Thorne SR, Hegarty P, Hepper EG. Love is heterosexual-by-default: Cultural heterosexism in default prototypes of romantic love. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2021; 60(2):653-77. [DOI:10.1111/bjso.12422] [PMID]

- Abdolmanafi A, Nobre P, Winter S, Tilley PJM, Jahromi RG. Culture and sexuality: Cognitive-emotional determinants of sexual dissatisfaction among Iranian and New Zealand women. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2018; 15(5):687-97. [DOI:10.1016/j.jsxm.2018.03.007] [PMID]

- Margulis AV, Pladevall M, Riera-Guardia N, Varas-Lorenzo C, Hazell L, Berkman ND, et al. Quality assessment of observational studies in a drug-safety systematic review, comparison of two tools: The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale and the RTI item bank. Clinical Epidemiology. 2014; 6:359-68. [DOI:10.2147/CLEP.S66677] [PMID]

- Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. European Journal of Epidemiology. 2010; 25(9):603-5. [DOI:10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z] [PMID]

- Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell PJ. The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; 2011. [Link]

- Ejder Apay S, Özorhan EY, Arslan S, Özkan H, Koc E, Özbey I. The sexual beliefs of Turkish men: comparing the beliefs of men with and without erectile dysfunction. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 2015; 41(6):661-71. [DOI:10.1080/0092623X.2014.966397] [PMID]

- Ejder Apay S, Nagorska M, Balcı Akpınar R, Sis Çelik A, Binkowska-Bury M. Student comparison of sexual myths: two-country case. Sexuality and Disability. 2013; 31:249-62. [DOI:10.1007/s11195-013-9301-0]

- Beydağ KD, Karabulutlu Ö. Nurses’ sexual myth beliefs and affecting factors. Ordu University Journal of Nursing Studies. 2021; 4(3):337-48. [DOI:10.38108/ouhcd.913652]

- Gökce S, Herkiloğlu D. Belief levels in sexual myths in women and effects of myths on sexual satisfaction. Front Womens Health. 2020; 5. [DOI:10.15761/FWH.1000182]

- Kukulu K, Gürsoy E, Sözer GA. Turkish university students’ beliefs in sexual myths. Sexuality and Disability. 2010; 27:49-59.[DOI:10.1007/s11195-009-9108-1]

- Ahmed F, Younis I, Abdel-Fattah M. Sexual myths in women. Benha Journal of Applied Sciences. 2020; 5(4 part (1)):107-23. [DOI:10.21608/bjas.2020.136261]

- Miah MA, Al-Mamun MA, Khan S, Mozumder MK. Sexual myths and behavior of male patients with psychosexual dysfunction in Bangladesh. Dhaka University Journal of Psychology. 2015; 39:89-100. [Link]

- Pacey S. Sensate Focus and the Psyche: Integrating sense and sexuality in couple therapy. London: Routledge; 2023. [DOI:10.4324/9781003328292]

- Hutner LA, Catapano LA, Nagle-Yang SM, Williams KE, Osborne LM, Textbook of women's reproductive mental health. Washington: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2022. [Link]

- Kaplan HS. Disorders of sexual desire and other new concepts and techniques in sex therapy. Brunner/Mazel; 1979. [Link]

- Pamela RC, Berscheid E. Lust: What we Know about Human Sexual Desire. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.; 1999. [Link]

- Doenau JH. The treatment of sexual dysfunction in marriage: strengths and limitations of Kaplan's modification of the Masters and Johnson model [MA thesis]. Canberra: The Australian National University (Australia); 1979. [Link]

- Ågmo A. On the intricate relationship between sexual motivation and arousal. Hormones and Behavior. 2011; 59(5):681-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2010.08.013] [PMID]

- Perelman MA. Helen Singer Kaplan’s Sexual Response Models and Legacy. In: Lykins AD, editor. Encyclopedia of Sexuality and Gender. Cham: Springer; 2023. [Link]

- Gebhard PH. Human sexual activity. Encyclopedia Britannica.2022. [Link]

- Ardhani NE, Dwi AA, Nuha MU, Perdana MP, Azzahra S, Lailiyah Z. Hubungan Body Image dengan Self-Esteem Mahasiswi Fakultas Ilmu Keolahragaan Universitas Negeri Semarang. Jurnal Analis. 2023; 2(1):37-44. [Link]

- Poovey KN. Women’s body image and sexual pleasure: Examining serial mediation by approach and avoidance sexual motives and distraction [MA thesis]. Carolina: Western Carolina University; 2021. [Link]

- Brandon-Friedman RA, Snedecor RD, Winter VR. Intersections between Body Image, Sexual Identity, and Sexual Well-Being among Gender-Diverse Youth. In: Dodd SJ, editor. The Routledge International Handbook of Social Work and Sexualities. London: Routledge 2021. [DOI:10.4324/9780429342912-14]

- Mushy SE, Rosser BRS, Ross MW, Lukumay GG, Mgopa LR, Bonilla Z, et al. The management of masturbation as a sexual health issue in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: A qualitative study of health professionals' and medical students' perspectives. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2021; 18(10):1690-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.jsxm.2021.07.007] [PMID]

- Çankaya S, Dikmen HA. The Impact of Engaged Couples' Sexual Knowledge and Beliefs on Their Beliefs and Attitudes Towards Marriage. Turkish Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care. 2019; 13(4):427-36. [DOI:10.21763/tjfmpc.550471]

- Güner TA. The effect of sexual myths on quality of sexual life, marital satisfaction and self-esteem in married women with physically disabled. In: Karaman E, Önder GO, editors. Current Researches in Health Sciences-II. İstanbul: Ozgur; 2023. [Link]

- Moghaddam-Banaem L, Khani S, Mohamadi E, Vedadhir AA, Hajizadeh E. [Non-responding health system to Women’s sexual and reproductive health needs: A mixed method study (Persian)]. Journal of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences. 2018; 28(160):88-105. [Link]

- Evcili F, Golbasi Z. Sexual myths and sexual health knowledge levels of Turkish university students. Sexuality & Culture. 2017; 21:976-90. [DOI:10.1007/s12119-017-9436-8]

- Aker S, Şahin M, Oğuz G. Sexual myth beliefs and associated factors in university students. Turkish Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care. 2019; 13(4):472-80. [DOI:10.21763/tjfmpc.653462]

- Kasaeian A, Weidenauer C, Hautzinger M, Randler C. Reproductive success, relationship orientation, and sexual behavior in heterosexuals: Relationship with chronotype, sleep, and sex. Evolutionary Psychology. 2019; 17(3):1474704919859760. [DOI:10.1177/1474704919859760] [PMID]

- Karabulutlu Ö, Yılmaz D. Sexual Myths Among University Students by Gender. Sted. 2018; 27(3):155-64. [Link]

- Afzali M, Khani S, Hamzehgardeshi Z, Mohammadpour RA, Elyasi F. Investigation of the social determinants of sexual satisfaction in Iranian Women. Sexual Medicine. 2020; 8(2):290-6. [DOI:10.1016/j.esxm.2020.02.002] [PMID]

Type of Study: Review Article |

Subject:

Midwifery

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |