Volume 12, Issue 4 (Autumn 2024)

Iran J Health Sci 2024, 12(4): 317-322 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: IR.MAZUMS.REC.1397.D113

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Marzband R, Hosseini S H, Hamzehgardeshi Z, Moosazadeh M, Eslamijouybari M, Yaghoubi T, et al . A Spiritual Care Program for Patients With Cancer and Psychosomatic Disorders in Iran: A Protocol Study. Iran J Health Sci 2024; 12 (4) :317-322

URL: http://jhs.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-959-en.html

URL: http://jhs.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-959-en.html

Rahmatollah Marzband

, Seyed Hamzeh Hosseini *

, Seyed Hamzeh Hosseini *

, Zeinab Hamzehgardeshi

, Zeinab Hamzehgardeshi

, Mahmood Moosazadeh

, Mahmood Moosazadeh

, Mohammad Eslamijouybari

, Mohammad Eslamijouybari

, Tahereh Yaghoubi

, Tahereh Yaghoubi

, Marzieh Azizi

, Marzieh Azizi

, Fereshteh Araghian Mojarad

, Fereshteh Araghian Mojarad

, Ehsan Abedini

, Ehsan Abedini

, Seyed Hamzeh Hosseini *

, Seyed Hamzeh Hosseini *

, Zeinab Hamzehgardeshi

, Zeinab Hamzehgardeshi

, Mahmood Moosazadeh

, Mahmood Moosazadeh

, Mohammad Eslamijouybari

, Mohammad Eslamijouybari

, Tahereh Yaghoubi

, Tahereh Yaghoubi

, Marzieh Azizi

, Marzieh Azizi

, Fereshteh Araghian Mojarad

, Fereshteh Araghian Mojarad

, Ehsan Abedini

, Ehsan Abedini

Department of Psychiatry, Psychosomatic Research Center, Faculty of Medicine, Sari Imam Khomeini Hospital, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran. , shhosseini@mazums.ac.ir

Full-Text [PDF 611 kb]

(642 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1865 Views)

Full-Text: (657 Views)

Introduction

Chronic disorders are considered as the leading causes of mortality worldwide. They account for 60% of death cases in the world [1]. They can threaten patients’ well-being and personal and social relationships and may negatively affect their psychological health [2, 3]. Cancers and psychosomatic disorders are among the most common chronic diseases in Iran and the world [4]. In 2024, there were 2,001,140 new cancer cases and 611,720 cancer deaths in the United States [5]. Various potential reasons lead to the increased prevalence of cancer worldwide, including increased life expectancy and changes in environmental exposure to risk factors, carcinogenic products, infectious microorganisms, and random gene mutations [4, 6]. Psychosomatic disorders are characterized by specific somatic symptoms or pathological causes, and their formation or exacerbation is strongly affected by psychological factors such as stress [7-9]. The somatic changes are similar to the physiological changes in the patient’s emotional status but are more vital and constant [7, 8]. Psychosomatic complaints account for one-third of patients’ first visits to the hospitals [8]. A study showed that 64.6% of women and 35.4% of men had psychosomatic disorders [10]. Factors such as female gender, lower educational level, unemployment, lower socioeconomic status, chronic pain disorders, and living in developed countries are among the most common risk factors for the onset of psychosomatic disorders [7, 8]. The cancers and psychosomatic disorders put a high economic burden on the health system. Therefore, effective palliative treatment is essential in managing these patients [11].

For patients with chronic diseases, spiritual therapy can be a cost-effective treatment method. Considering the impact of spirituality on health, the World Health Organization and other international associations have emphasized the importance of spiritual care as an essential part of palliative nursing care [12]. Since health professionals and medical staff may not have the knowledge required to meet the spiritual needs of patients, it is crucial to use health professionals with competency in identifying spiritual needs and providing appropriate responses in clinical settings [13]. Several models have been designed to deliver spiritual care to patients. Some of these models are focused on the spiritual health outcomes of spiritual care. One of these models suggests that the purpose of spiritual care is to reduce depression and feelings of helplessness and hopelessness among patients with incurable diseases. Since several characteristics of spiritual health (including spiritual transcendence, purposefulness, and sense of dignity) are closely associated with pain control, quality of life, and adaptation to loss, palliative care providers are encouraged to understand these physical and psychological stimuli that affect the spiritual health of patients. Understanding the physical, mental, and emotional challenges of terminally ill patients is essential for having a positive impact on their spiritual and overall health [14].

The majority of the population in Iran is Muslim, and most have been raised based on Islamic values. Belief in Islam can considerably affect a person’s spirituality, spiritual challenges, and use of spiritual strategies in the face of diseases [15]. Many spiritual therapies used in Iranian studies in this field are non-native and based on the models designed for Western (non-Muslim) populations [16]. However, some studies in Iran have suggested guidelines on how to provide spiritual care. In one of these studies, it has been recommended that the first step in delivering spiritual care is to identify the patient’s spiritual needs, and attention, guidance, and intervention have been cited as the essential elements of spiritual care [17]. The Office for Health Technology Assessment and Tariff System of the Iranian Ministry of Health and Medical Education has recently provided some guidelines for delivering spiritual services to cancer patients [17, 18].

Due to the increase in cancer and psychosomatic disorders and the related treatment costs in Iran, there is a need to include effective non-pharmacological interventions such as spiritual care in the treatment process. In this regard, a spiritual care program should be designed based on the managerial structure of the hospitals and the Iranian culture. This study aims to develop, implement, and evaluate a spiritual care program for Iranian patients with cancer and psychosomatic disorders.

Materials and Methods

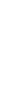

This is a mixed-method protocol study that will be conducted at the oncology and psychosomatic units of Imam Khomeini Hospital, affiliated to Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences in Iran. Figure 1 illustrates the steps that will be taken to conduct the study.

Systematic literature review

We will first define the study questions based on the PICO criteria as follows: Population (patients with cancers and psychosomatic disorders), intervention (spiritual care), comparison (routine care), and outcome (improvement of health dimensions). Based on the research question, a systematic search in Google Scholar and databases such as PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, Scientific Information Database (SID]), and MagIran will be carried out to identify the related studies in the field of spiritual care and spiritual health in patients with cancers and psychosomatic disorders. To search in the mentioned databases, medical subject headings (Mesh), including spiritual, spirituality, spiritual health, spiritual care, spiritual needs, cancer, neoplasm, carcinoma, psychosomatic, psychiatry, sleep disorders, depression, and anxiety, will be used by applying the Boolean operators (OR, AND). The time considered for the search is from 2015 to 2023. The inclusion criteria for the articles will be: Being randomized clinical trials (RCT) or quasi-experimental studies published in valid scientific journals, study of spiritual care for patients with cancers and psychosomatic disorders, and published in Persian and English. Articles published at national or international conferences and studies with unavailable full texts will be excluded from this study. The articles found will be entered into EndNote software, version X7, and two authors (Seyed Hamzeh Hosseini and Tahereh Yaghoubi) independently will screen their titles and abstracts according to the eligibility criteria. The disagreements between them will be resolved through consensus or using the opinions of the third author (Rahmatollah Marzband).

The critical appraisal skills program (CASP) checklist will be used to assess the quality of RCTs included in the systematic review [19]. The authors (Seyed Hamzeh Hosseini and Tahereh Yaghoubi) will independently evaluate the included studies based on the CASP criteria for RCTs. According to the strengths and weaknesses of the studies, they will be graded as “high”, “moderate”, and “low”. The tool generates binary scores: 1 for “satisfied” and 0 for “unsatisfied” items [20].

Designing and finalizing the content of the spiritual care program

The research team will hold two online meetings with the participation of experts (psychiatrists, oncologists, psychologists, nurses, and spiritual care experts) to finalize the content of the spiritual care program. In the first session, the first author will present the qualitative phase results and the reviewed studies’ characteristics to the expert team. Then, online and face-to-face meetings will be held to discuss the content. At the end of the first session, a checklist designed to rank the educational materials based on importance and feasibility will be sent to the experts. The experts will recommend the most effective materials by completing the designed checklist and returning it. The submitted content will be reviewed, and the materials with the highest scores will be selected as the most important. The second meeting with the experts will be held the week after the first meeting to report the results of the experts’ opinions.

Determining the content validity of the spiritual care program

To determine the content validity of the program, the Persian version of the appraisal of guidelines for research and evaluation instrument II (AGREE II), along with the final draft, will be emailed to the experts to cooperate in evaluating the educational program and send back their recommendations to the first author through email. The AGREE II tool evaluates overall guideline quality, recommendation for use, and the possible success in achieving the appropriate behavioral outcome. It has 23 appraisal criteria and six domains: Scope and purpose (3 items), stakeholder involvement (4 items), rigor of development (7 items), clarity of presentation (3 items), applicability (4 items), and editorial independence (2 items). The experts will rate based on applicability (1=very low, 2=low, 3=high, 4= very high), being scientific from 1 (completely disagree) to 4 (completely agree), and necessity from 1 (completely disagree) to 4 (completely agree). Then, their opinions will be used to validate the designed program. If the expert consensus is fulfilled at 75 %, the program will be considered valid [21].

Determining the indicators for the target population

For the detailed discussion of practical concepts in spiritual care, an evaluation checklist will be sent for doctors, nurses, and spiritual care service providers, and the religious practices (ablution, praying, and fasting) and hospital accreditation criteria in the field of spiritual care (determination of the Qibla direction in all rooms, patient’s ability to perform ablution on earth surface or sand, patient’s access to the Qur’an and prayer, patient’s access to prayer stones (Turbah) and other prayer tools, creating a suitable space for the patient to pray, informing the time of Adhan (call to prayer) to the patient by the ward staff), and duration of hospitalization will be used as the indicators for evaluation.

To measure the effectiveness of the designed program, the mentioned indicators will be assessed before and after the intervention by using the hospital anxiety and depression scale [22], distress tolerance scale [23], hospital service satisfaction questionnaire [24, 25], and spiritual well-being questionnaire [26].

Implementation of the designed program and measurement of indicators

After preparing the final draft, it will be implemented on patients with psychosomatic disorders and cancers in Imam Khomeini Hospital, Sari, Iran. The indicators before and after the intervention will be analyzed. The normality of the data distribution will be assessed using Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The t-test will be used for the analysis of quantitative variables with normal distribution, while the chi-square test will be performed for qualitative variables in SPSS software, version 24.

Discussion

This study aimed to report a protocol for designing a spiritual care program for Iranian patients with cancer and psychosomatic disorders. According to a review study, many adult patients with cancer have spiritual needs and expect the treatment staff to address their spiritual needs. Also, the study reported that the spiritual needs of patients with cancer are infrequently addressed in medical settings [27]. Spirituality positively affects the risk factors for cancer and can reduce depression, anxiety, and the recurrence of psychiatric disorders [28]. In nursing studies, spirituality has been defined as a sense of connection to a set of values such as love, respect, dignity, empathy, search for meaning in life, and relationship with self and others, which may or may not be related to religion [29]. In Iran, most people have been raised based on Islamic beliefs and values. In such Islamic culture, belief in Allah is the basis of spirituality. In such a culture, spiritual care refers to any care given based on such belief and the effort to meet the spiritual needs of the patients [30]. Moosavi et al., in a study on spiritual care for cancer patients, developed a clinical practice guideline for oncology nurses in Iran. They provided 84 evidence-based recommendations in three main areas, including human resources, care settings, and the process of spiritual care. They suggested that healthcare organizations should help create spiritual care teams under the supervision of oncology nurses with qualified healthcare providers and one trained clergy [31].

To introduce the concept of spiritual care for patients with cancer and psychosomatic disorders in Iran, health professionals need to reach a common understanding of practical strategies for assessing spirituality in patients and design spiritual interventions tailored to Iranian culture. To design the spiritual care program, we will review the existing guidelines and protocols to develop a more practical program for Iranians. The mixed-method design of this study will allow us to survey the attitudes of health professionals toward spirituality and spiritual care by combining quantitative and qualitative data. We will implement the developed program in a hospital, and will assess its impact on the satisfaction of patients with cancer and psychosomatic disorders.

Conclusion

Spiritual care is important for increasing recovery and reducing the length of stay in Muslim patients, especially those hospitalized due to psychosomatic disorders and cancers. The provision of spiritual care services in hospitals requires a standard protocol. In this regard, we will design a spiritual care protocol for Iranian patients with cancer and psychosomatic disorders, which can also be used in the accreditation of hospitals in Iran.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran (Code: IR.MAZUMS.REC.1397.301).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization and supervision: Rahmatollah Marzband and Seyed Hamzeh Hosseini; Methodology: Tahereh Yaghoubi, Fereshteh Araghian Mojarad, Zeinab Hamzehgardeshi, and Marzieh Azizi; Data collection: Mahmood Moosazadeh, and Mohammad Eslamijouybari; Data analysis: Mahmood Moosazadeh and Ehsan Abedini; Funding acquisition and resources: Seyed Hamzeh Hosseini; Investigation and writing: Tahereh Yaghoubi, Marzieh Azizi, Mohammad Eslamijouybari, and Seyed Hamzeh Hosseini.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran for supporting this research.

References

Chronic disorders are considered as the leading causes of mortality worldwide. They account for 60% of death cases in the world [1]. They can threaten patients’ well-being and personal and social relationships and may negatively affect their psychological health [2, 3]. Cancers and psychosomatic disorders are among the most common chronic diseases in Iran and the world [4]. In 2024, there were 2,001,140 new cancer cases and 611,720 cancer deaths in the United States [5]. Various potential reasons lead to the increased prevalence of cancer worldwide, including increased life expectancy and changes in environmental exposure to risk factors, carcinogenic products, infectious microorganisms, and random gene mutations [4, 6]. Psychosomatic disorders are characterized by specific somatic symptoms or pathological causes, and their formation or exacerbation is strongly affected by psychological factors such as stress [7-9]. The somatic changes are similar to the physiological changes in the patient’s emotional status but are more vital and constant [7, 8]. Psychosomatic complaints account for one-third of patients’ first visits to the hospitals [8]. A study showed that 64.6% of women and 35.4% of men had psychosomatic disorders [10]. Factors such as female gender, lower educational level, unemployment, lower socioeconomic status, chronic pain disorders, and living in developed countries are among the most common risk factors for the onset of psychosomatic disorders [7, 8]. The cancers and psychosomatic disorders put a high economic burden on the health system. Therefore, effective palliative treatment is essential in managing these patients [11].

For patients with chronic diseases, spiritual therapy can be a cost-effective treatment method. Considering the impact of spirituality on health, the World Health Organization and other international associations have emphasized the importance of spiritual care as an essential part of palliative nursing care [12]. Since health professionals and medical staff may not have the knowledge required to meet the spiritual needs of patients, it is crucial to use health professionals with competency in identifying spiritual needs and providing appropriate responses in clinical settings [13]. Several models have been designed to deliver spiritual care to patients. Some of these models are focused on the spiritual health outcomes of spiritual care. One of these models suggests that the purpose of spiritual care is to reduce depression and feelings of helplessness and hopelessness among patients with incurable diseases. Since several characteristics of spiritual health (including spiritual transcendence, purposefulness, and sense of dignity) are closely associated with pain control, quality of life, and adaptation to loss, palliative care providers are encouraged to understand these physical and psychological stimuli that affect the spiritual health of patients. Understanding the physical, mental, and emotional challenges of terminally ill patients is essential for having a positive impact on their spiritual and overall health [14].

The majority of the population in Iran is Muslim, and most have been raised based on Islamic values. Belief in Islam can considerably affect a person’s spirituality, spiritual challenges, and use of spiritual strategies in the face of diseases [15]. Many spiritual therapies used in Iranian studies in this field are non-native and based on the models designed for Western (non-Muslim) populations [16]. However, some studies in Iran have suggested guidelines on how to provide spiritual care. In one of these studies, it has been recommended that the first step in delivering spiritual care is to identify the patient’s spiritual needs, and attention, guidance, and intervention have been cited as the essential elements of spiritual care [17]. The Office for Health Technology Assessment and Tariff System of the Iranian Ministry of Health and Medical Education has recently provided some guidelines for delivering spiritual services to cancer patients [17, 18].

Due to the increase in cancer and psychosomatic disorders and the related treatment costs in Iran, there is a need to include effective non-pharmacological interventions such as spiritual care in the treatment process. In this regard, a spiritual care program should be designed based on the managerial structure of the hospitals and the Iranian culture. This study aims to develop, implement, and evaluate a spiritual care program for Iranian patients with cancer and psychosomatic disorders.

Materials and Methods

This is a mixed-method protocol study that will be conducted at the oncology and psychosomatic units of Imam Khomeini Hospital, affiliated to Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences in Iran. Figure 1 illustrates the steps that will be taken to conduct the study.

Systematic literature review

We will first define the study questions based on the PICO criteria as follows: Population (patients with cancers and psychosomatic disorders), intervention (spiritual care), comparison (routine care), and outcome (improvement of health dimensions). Based on the research question, a systematic search in Google Scholar and databases such as PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, Scientific Information Database (SID]), and MagIran will be carried out to identify the related studies in the field of spiritual care and spiritual health in patients with cancers and psychosomatic disorders. To search in the mentioned databases, medical subject headings (Mesh), including spiritual, spirituality, spiritual health, spiritual care, spiritual needs, cancer, neoplasm, carcinoma, psychosomatic, psychiatry, sleep disorders, depression, and anxiety, will be used by applying the Boolean operators (OR, AND). The time considered for the search is from 2015 to 2023. The inclusion criteria for the articles will be: Being randomized clinical trials (RCT) or quasi-experimental studies published in valid scientific journals, study of spiritual care for patients with cancers and psychosomatic disorders, and published in Persian and English. Articles published at national or international conferences and studies with unavailable full texts will be excluded from this study. The articles found will be entered into EndNote software, version X7, and two authors (Seyed Hamzeh Hosseini and Tahereh Yaghoubi) independently will screen their titles and abstracts according to the eligibility criteria. The disagreements between them will be resolved through consensus or using the opinions of the third author (Rahmatollah Marzband).

The critical appraisal skills program (CASP) checklist will be used to assess the quality of RCTs included in the systematic review [19]. The authors (Seyed Hamzeh Hosseini and Tahereh Yaghoubi) will independently evaluate the included studies based on the CASP criteria for RCTs. According to the strengths and weaknesses of the studies, they will be graded as “high”, “moderate”, and “low”. The tool generates binary scores: 1 for “satisfied” and 0 for “unsatisfied” items [20].

Designing and finalizing the content of the spiritual care program

The research team will hold two online meetings with the participation of experts (psychiatrists, oncologists, psychologists, nurses, and spiritual care experts) to finalize the content of the spiritual care program. In the first session, the first author will present the qualitative phase results and the reviewed studies’ characteristics to the expert team. Then, online and face-to-face meetings will be held to discuss the content. At the end of the first session, a checklist designed to rank the educational materials based on importance and feasibility will be sent to the experts. The experts will recommend the most effective materials by completing the designed checklist and returning it. The submitted content will be reviewed, and the materials with the highest scores will be selected as the most important. The second meeting with the experts will be held the week after the first meeting to report the results of the experts’ opinions.

Determining the content validity of the spiritual care program

To determine the content validity of the program, the Persian version of the appraisal of guidelines for research and evaluation instrument II (AGREE II), along with the final draft, will be emailed to the experts to cooperate in evaluating the educational program and send back their recommendations to the first author through email. The AGREE II tool evaluates overall guideline quality, recommendation for use, and the possible success in achieving the appropriate behavioral outcome. It has 23 appraisal criteria and six domains: Scope and purpose (3 items), stakeholder involvement (4 items), rigor of development (7 items), clarity of presentation (3 items), applicability (4 items), and editorial independence (2 items). The experts will rate based on applicability (1=very low, 2=low, 3=high, 4= very high), being scientific from 1 (completely disagree) to 4 (completely agree), and necessity from 1 (completely disagree) to 4 (completely agree). Then, their opinions will be used to validate the designed program. If the expert consensus is fulfilled at 75 %, the program will be considered valid [21].

Determining the indicators for the target population

For the detailed discussion of practical concepts in spiritual care, an evaluation checklist will be sent for doctors, nurses, and spiritual care service providers, and the religious practices (ablution, praying, and fasting) and hospital accreditation criteria in the field of spiritual care (determination of the Qibla direction in all rooms, patient’s ability to perform ablution on earth surface or sand, patient’s access to the Qur’an and prayer, patient’s access to prayer stones (Turbah) and other prayer tools, creating a suitable space for the patient to pray, informing the time of Adhan (call to prayer) to the patient by the ward staff), and duration of hospitalization will be used as the indicators for evaluation.

To measure the effectiveness of the designed program, the mentioned indicators will be assessed before and after the intervention by using the hospital anxiety and depression scale [22], distress tolerance scale [23], hospital service satisfaction questionnaire [24, 25], and spiritual well-being questionnaire [26].

Implementation of the designed program and measurement of indicators

After preparing the final draft, it will be implemented on patients with psychosomatic disorders and cancers in Imam Khomeini Hospital, Sari, Iran. The indicators before and after the intervention will be analyzed. The normality of the data distribution will be assessed using Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The t-test will be used for the analysis of quantitative variables with normal distribution, while the chi-square test will be performed for qualitative variables in SPSS software, version 24.

Discussion

This study aimed to report a protocol for designing a spiritual care program for Iranian patients with cancer and psychosomatic disorders. According to a review study, many adult patients with cancer have spiritual needs and expect the treatment staff to address their spiritual needs. Also, the study reported that the spiritual needs of patients with cancer are infrequently addressed in medical settings [27]. Spirituality positively affects the risk factors for cancer and can reduce depression, anxiety, and the recurrence of psychiatric disorders [28]. In nursing studies, spirituality has been defined as a sense of connection to a set of values such as love, respect, dignity, empathy, search for meaning in life, and relationship with self and others, which may or may not be related to religion [29]. In Iran, most people have been raised based on Islamic beliefs and values. In such Islamic culture, belief in Allah is the basis of spirituality. In such a culture, spiritual care refers to any care given based on such belief and the effort to meet the spiritual needs of the patients [30]. Moosavi et al., in a study on spiritual care for cancer patients, developed a clinical practice guideline for oncology nurses in Iran. They provided 84 evidence-based recommendations in three main areas, including human resources, care settings, and the process of spiritual care. They suggested that healthcare organizations should help create spiritual care teams under the supervision of oncology nurses with qualified healthcare providers and one trained clergy [31].

To introduce the concept of spiritual care for patients with cancer and psychosomatic disorders in Iran, health professionals need to reach a common understanding of practical strategies for assessing spirituality in patients and design spiritual interventions tailored to Iranian culture. To design the spiritual care program, we will review the existing guidelines and protocols to develop a more practical program for Iranians. The mixed-method design of this study will allow us to survey the attitudes of health professionals toward spirituality and spiritual care by combining quantitative and qualitative data. We will implement the developed program in a hospital, and will assess its impact on the satisfaction of patients with cancer and psychosomatic disorders.

Conclusion

Spiritual care is important for increasing recovery and reducing the length of stay in Muslim patients, especially those hospitalized due to psychosomatic disorders and cancers. The provision of spiritual care services in hospitals requires a standard protocol. In this regard, we will design a spiritual care protocol for Iranian patients with cancer and psychosomatic disorders, which can also be used in the accreditation of hospitals in Iran.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran (Code: IR.MAZUMS.REC.1397.301).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization and supervision: Rahmatollah Marzband and Seyed Hamzeh Hosseini; Methodology: Tahereh Yaghoubi, Fereshteh Araghian Mojarad, Zeinab Hamzehgardeshi, and Marzieh Azizi; Data collection: Mahmood Moosazadeh, and Mohammad Eslamijouybari; Data analysis: Mahmood Moosazadeh and Ehsan Abedini; Funding acquisition and resources: Seyed Hamzeh Hosseini; Investigation and writing: Tahereh Yaghoubi, Marzieh Azizi, Mohammad Eslamijouybari, and Seyed Hamzeh Hosseini.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran for supporting this research.

References

- Rezaei H, Niksima SH, Ghanei Gheshlagh R. Burden of Care in Caregivers of Iranian patients with chronic disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2020; 18(1):261. [DOI:10.1186/s12955-020-01503-z] [PMID]

- Landry LN. Chronic illness, well-being, and social values. In: Michael Reynolds J, Wieseler C, editors. The disability bioethics reader. New York: Routledge; 2022. [Link]

- Najafi K, Khoshab H, Rahimi N, Jahanara A. Relationship between spiritual health with stress, anxiety and depression in patients with chronic diseases. International Journal of Africa Nursing Sciences. 2022; 17:100463. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijans.2022.100463]

- Mitchell PD, Dittmar JM, Mulder B, Inskip S, Littlewood A, Cessford C, et al. The prevalence of cancer in Britain before industrialization. Cancer. 2021; 127(17):3054-9. [DOI:10.1002/cncr.33615] [PMID]

- Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2024; 74(1):12-49. [DOI:10.3322/caac.21820] [PMID]

- Rifkin RF, Potgieter M, Ramond JB, Cowan DA. Ancient oncogenesis, infection and human evolution. Evolutionary Applications. 2017; 10(10):949-64. [DOI:10.1111/eva.12497] [PMID]

- Nisar H, Srivastava R. Fundamental concept of psychosomatic disorders: A review. International Journal of contemporary Medicine Surgery and Radiology. 2018; 3(1):12-18. [Link]

- Liu Y, Li H. Psychosomatic Disorders and Family Factors. 2021; 123-8. [Link]

- Patel M, Patel K. Concepts of psychosomatic conditions. Journal of Alternative Medicine Research. 2022; 14(3):287-97. [Link]

- Torrubia-Pérez E, Reverté-Villarroya S, Fernández-Sáez J, Martorell-Poveda MA. Analysis of psychosomatic disorders according to age and sex in a rural area: A population-based study. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2022; 12(10):1730. [DOI:10.3390/jpm12101730] [PMID]

- Jabbari A, Hadian M, Mazaheri E, Jelodar ZK. The economic cost of cancer treatment in Iran. Journal of Education and Health Promotion. 2023; 12:32. [DOI:10.4103/jehp.jehp_928_21] [PMID]

- O'Shea ER, Wallace M, Griffin MQ, Fitzpatrick JJ. The effect of an educational session on pediatric nurses’ perspectives toward providing spiritual care. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2011; 26(1):34-43. [DOI:10.1016/j.pedn.2009.07.009] [PMID]

- Zare A, Jahandideh S. [The impact of special wards nursing spiritual well-being upon patients’ spiritual care (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Nursing Research. 2014; 9(3):30-8. [Link]

- Chochinov HM, Cann BJ. Interventions to enhance the spiritual aspects of dying. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2005; 8(supplement 1):s-103-s-15. [DOI:10.1089/jpm.2005.8.s-103] [PMID]

- Rassool GH. Cultural competence in nursing Muslim Patients. Nursing Times. 2015; 111(14):12-5. [PMID]

- Memaryan N, Ghaempanah Z, Seddigh R. Spiritual interventions in Iran: A review article. SOJ Psychology. 3 (1):1-5. Spiritual interventions in Iran: A review article. 2017; 4(1):1-5. [DOI:10.15226/2374-6874/4/1/00135]

- Memaryan N, Jolfaei AG, Ghaempanah Z, Shirvani A, Vand HD, Bolhari J. Spiritual care for cancer patients in Iran. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2016; 17(9):4289-94. [Link]

- Memaryan N, Ghaempanah Z, Saeedi MM, Aryankhesal A, Ansarinejad N, Seddigh R. Content of spiritual counselling for cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy in Iran: A qualitative content analysis. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention: APJCP. 2017; 18(7):1791-7. [PMID]

- Di Lazzaro V, Oliviero A, Profice P, Pennisi MA, Pilato F, Zito G, et al. Ketamine increases human motor cortex excitability to transcranial magnetic stimulation. The Journal of Physiology. 2003; 547(2):485-96. [DOI:10.1113/jphysiol.2002.030486] [PMID]

- Long HA, French DP, Brooks JM. Optimising the value of the critical appraisal skills programme (CASP) tool for quality appraisal in qualitative evidence synthesis. Research Methods in Medicine & Health Sciences. 2020; 1(1):31-42. [DOI:10.1177/2632084320947559]

- Polit DF, Beck CT. Essentials of nursing research: Appraising evidence for nursing practice. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010. [Link]

- Amini P, Maroufizadeh S, Omani Samani R. Evaluating the factor structure, item analyses, and internal consistency of hospital anxiety and depression scale in Iranian infertile patients. International Journal of Reproductive BioMedicine. 2017; 15(5):287-96. [DOI:10.29252/ijrm.15.5.287] [PMID]

- Zarrin Makan M, Sadeghi N, Mousavi M S, Jafari-Mianaei S. [Effects of reminiscence on distress tolerance and spiritual health of mothers with premature newborns admitted to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit of Shahid Beheshti Hospital in Isfahan, Iran (Persian)]. Avicenna Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Care. 2023; 31(1):38-45. [DOI:10.32592/ajnmc.31.1.38]

- Mahdavi MS, Hojjat Doost M, Parvardeh Z, Gholami Fesharaki M [Standardization and investigation of psychological characteristics of the telephone questionnaire for satisfaction of hospitalized patients of Baqiyatullah (a.s) (Persian)]. Military Medicine. 2022; 15(4):281-6. [Link]

- Nikpour A, Gholami Fesharaki M. [Standardization of patients’ satisfaction questionnaire referring to emergency department of Najmie Hospital (Persian)]. Navid No. 2019; 22(71):41-9. [DOI:10.22038/nnj.2019.41937.1172]

- Abhari MB, Fisher JW, Kheiltash A, Nojomi M. Validation of the Persian version of spiritual well-being questionnaires. Iranian Journal of Medical Sciences. 2018; 43(3):276-85. [PMID]

- Mercier M, Maglio J, Almhanna K, Guyer D. Spiritual care for adult patients with cancer: From maintaining hope and respecting cultures to supporting survivors-a narrative review. Annals of Palliative Medicine. 2023; 12(5):1047-58. [DOI:10.21037/apm-22-1274] [PMID]

- Turke KC, Canonaco JS, Artioli T, Lima MSS, Batlle AR, Oliveira FCP, et al. Depression, anxiety and spirituality in oncology patients. Revista da Associacao Medica Brasileira (1992). 66(7):960-5. [DOI:10.1590/1806-9282.66.7.960] [PMID]

- Fallahi Khoshkenab M. The process of spiritual care in rehabilitation of cancer patients: A grounded theory study. Medical-Surgical Nursing Journal. 2015; 4(3):e88209. [Link]

- Coward HJ, Stajduhar KI, Bramadat P. Spirituality in hospice palliative care. New York: State University of New York Press; 2013. [Link]

- Moosavi S, Borhani F, Akbari ME, Sanee N, Rohani C. Recommendations for spiritual care in cancer patients: A clinical practice guideline for oncology nurses in Iran. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2020; 28(11):5381-95. [DOI:10.1007/s00520-020-05390-4] [PMID]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |