Volume 13, Issue 2 (Spring 2025)

Iran J Health Sci 2025, 13(2): 133-144 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Ramaji T, Yazdani F. The Association Between Obesity and Anemia With Pregnancy and Childbirth Outcomes. Iran J Health Sci 2025; 13 (2) :133-144

URL: http://jhs.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-980-en.html

URL: http://jhs.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-980-en.html

Health Sciences Research Center, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran. , fereshteh_yazdani68@yahoo.com

Full-Text [PDF 814 kb]

(95 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (319 Views)

Full-Text: (5 Views)

Introduction

Pregnancy is one of the most critical periods in the life of a mother and her child, and it is essential in terms of social health for the individual, family and society. The mother’s health during this period affects not only her quality of life but also the life and health of the fetus and future generations’ lives and health [1]. Obesity during pregnancy is one of the main worldwide health problems and it can lead to several adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes, such as gestational diabetes mellitus, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, labor induction, chorioamnionitis, and macrosomia [2, 3]. The World Health Organization (WHO) has considered body mass index (BMI) values above 25 and 30 as overweight and obese, respectively [4]. Based on research conducted in Iran in 2022 and 2017 and Saudi Arabia in 2021, the incidence of obesity and overweight among pregnant mothers was estimated to be 44.2%, 80.4%, and 47.8%, respectively [5, 6, 7]. According to some studies, obesity increases the risk of diabetes, fetal macrosomia, cesarean delivery and low birth weight, which are disturbing complications [8, 9, 10]. Some studies have also shown a relationship between maternal BMI and maternal anemia during pregnancy [11, 12].

Among the essential risks during pregnancy, iron deficiency anemia has been raised as one of the main nutritional and public health problems due to its high prevalence and adverse effects [13]. Anemia is the most prominent hematological manifestation during pregnancy and a dilemma of the WHO [14, 15]. Based on the definition of the WHO and the center for disease control, a hemoglobin concentration of <11 mg/dL in the first and third trimesters of pregnancy and less than 10.5 mg/dL in the second trimester of pregnancy is called gestational anemia [16-18]. Anemia is characterized by a decrease in hemoglobin, the number and volume of red blood cells and, as a result, a decrease in the capacity to carry oxygen in the blood circulation. Suppose dietary iron is not available to the body in sufficient quantity to generate red blood cells. In that case, the body first uses its reserves, and if iron deficiency continues, its reserves decrease and iron deficiency anemia occurs. The optimal concentration of hemoglobin required to respond to physiological needs differs according to age, gender, altitude of residence, smoking habits and pregnancy status [19, 20]. The prevalence of anemia in pregnancy varies significantly due to differences in social conditions, lifestyles and health behaviors in different cultures. Anemia can affect pregnant women all over the world [21].

In research in China and Canada, the prevalence of anemia in pregnant women was determined as 17.7% and 12.8%, respectively [22, 23]. In the meta-analysis of Karami et al., the prevalence of anemia in pregnant women was estimated as 36.8% [24]. Complications of gestational anemia in newborns include premature birth, low birth weight, neonatal anemia, growth delay and increased infant mortality. Maternal complications include an increased risk of postpartum infection, uterine inertia, increased maternal mortality rate and heart failure [25]. Various studies have also shown the relationship between anemia and complications such as low birth weight, preterm delivery, postpartum infection, and maternal mortality [26-28].

Given the increasing prevalence of obesity in pregnant women, as well as the importance of the effects of anemia and maternal weight before pregnancy on maternal and infant health during this period, the undesirable effects of obesity and anemia can be reduced by using simple preventive methods such as a healthy lifestyle (proper nutrition and exercise), appropriate diagnosis and treatment of anemia. Therefore, the present study was conducted to determine the relationship between anemia and obesity with pregnancy and childbirth outcomes in pregnant women referred to comprehensive health service centers in Tonekabon City, Iran, in 2023.

Material and Methods

Study design

This is a cross-sectional descriptive-analytical research.

Setting and participants

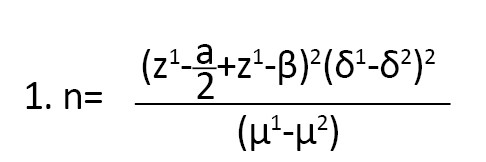

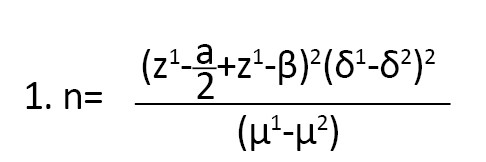

The research population comprised 240 women who gave birth between February and March 2022 and were postpartum. The sample size was estimated based on the prevalence of anemia research by Ali et al. using the Equation 1 with a confidence level of 95% and an error of 0.05 [29].

All samples had electronic health records in selected health centers. The inclusion criteria were all women who gave birth between 3 and 5 days before, had no chronic disease, did not use a special diet, had Iranian citizenship and lived in Tonekabon City, Iran. The exclusion criteria were unwillingness (referees to medical centers were invited to participate in the research through interviews; those willing gave the researcher access to the electronic health system by providing their national code) to participate in the research and multiple pregnancies.

Sample size and data collection

The authors presented the study to the city health network and obtained a letter of introduction. After referring to comprehensive urban health care centers and self-introductions, sufficient explanations about the topic, research objectives and how they would be implemented, the research was done in 2023. Further, assurances were made that the information on the research samples would remain confidential. Sampling was carried out using a multi-stage (stratified-cluster) method. Each of the comprehensive urban health care centers No. 3, 2, 1 and 4 of Tonekabon was considered a cluster, and the number of samples was proportional to the population covered by those centers (almost 4 centers had the same population covered). Based on the calculated sample size, 60 pregnant women were allocated to each cluster. Then, from each class, two centers (geographical area covered) were selected as clusters, and, considering the number of samples in each class, 30 pregnant women were selected from each center using a simple random method and entered the study.

The data collection tool is a checklist including personal and social characteristics (age, job, education level, height, weight, BMI at the beginning of pregnancy, less than 12 weeks), fertility history information (number of births, number of pregnancies, miscarriages, stillbirths), and information related to the consequences of pregnancy and childbirth (age pregnancy, type of delivery, gestational diabetes, sex of baby, birth weight). Scales and meters are valid tools for measuring weight and height. The reliability of the maternal scale with a standard weight of 2 kg, the reliability of the newborn scale with a standard weight of 500 g and the reliability of the meter with a standard wooden ruler were controlled and confirmed.

Blood tests (Hb, Hct) of the first trimester of pregnancy (6-10 weeks) and second trimester (16-20 weeks) were performed with a referral letter from pregnant women to a reference laboratory (Tonekabon County Health Center Laboratory), where the testing methods were the same. The device was calibrated every day by relevant experts.

It was extracted through the parsa (electronic health event file and referral) system by checking people’s electronic files. According to the WHO guidelines, pregnant women with hemoglobin less than 11 mg/dL were considered anemic [16, 17]. Anemic people were divided into three categories (severe anemia, less than 7; moderate, 7-10 and mild, 10-11 mg/dL) based on the hemoglobin concentration in the body [29 ,30].

Based on the WHO’s standard criteria, the women were categorized into 4 levels: Underweight (BMI less than 18.5 kg/m2), normal (18.5-24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25-29.9 kg/m2) and obese (more than 30 kg/m2) [31]. According to the WHO definition, a newborn weight below 2500 g is considered underweight. Then, the infant weight was divided into underweight, normal weight (2500-4000 g) and overweight (more than 4000 g). BMI was calculated by dividing weight (in kilograms) by the square of height (in meters). The mother’s weight was measured with light clothing using a standard scale and height using a standard meter mounted on the wall. The weight of the newborns at birth was also measured in the newborn ward without clothing using a standard scale for newborns in the supine position.

Statistical analysis

After collecting the data, they were analyzed using SPSS software, version 24. Descriptive statistics methods, central and dispersion indicators Mean±SD and frequency distribution were used to describe the characteristics of the research samples. To check the normality of the data, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used and to check the relationship of variables with anemia, the chi-square test (a significance level of zero means independence and no relationship between two variables) was used. An independent t-test was used to compare the average of two anemic and non-anemic groups with pregnancy outcomes. P<0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Sample description

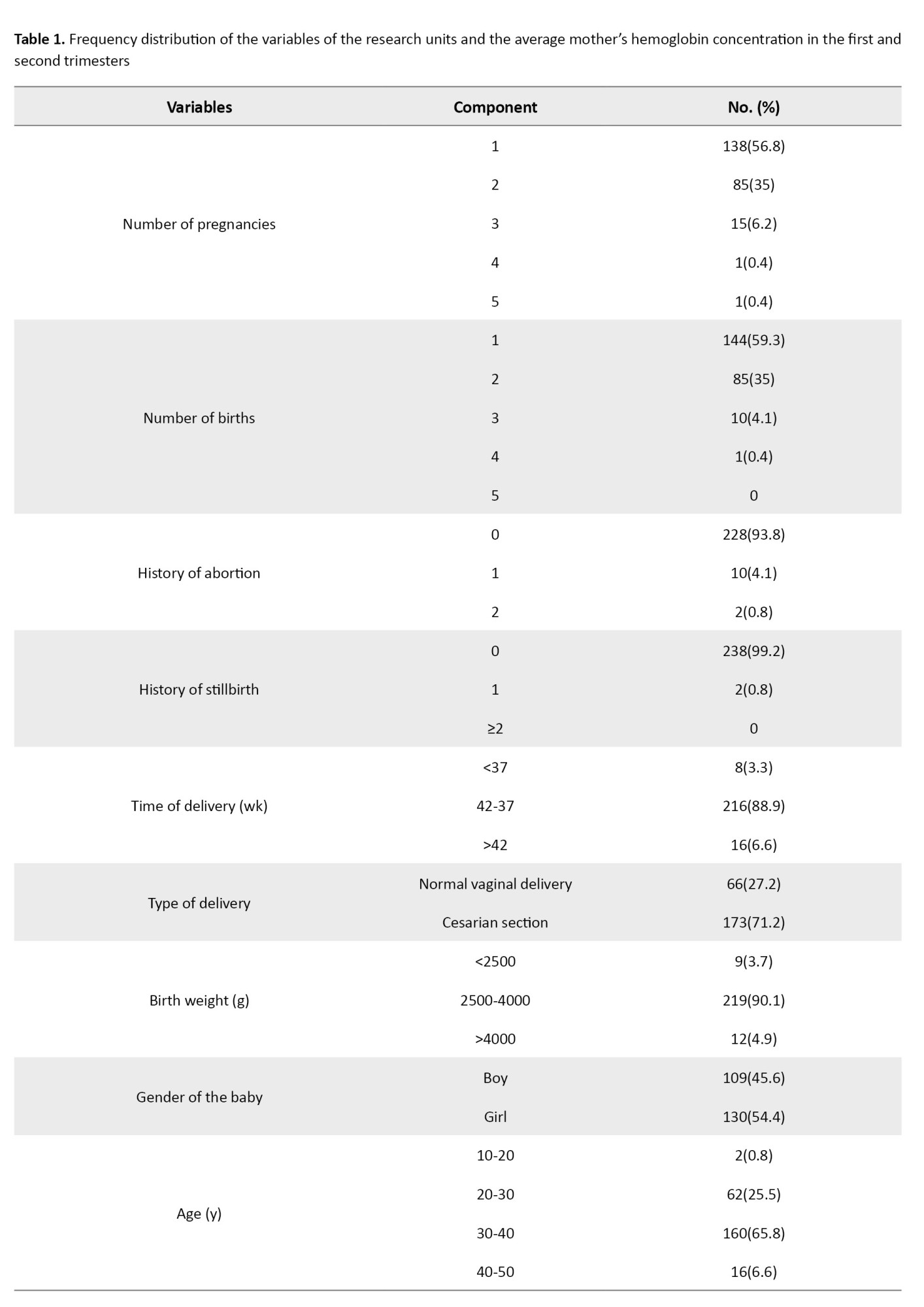

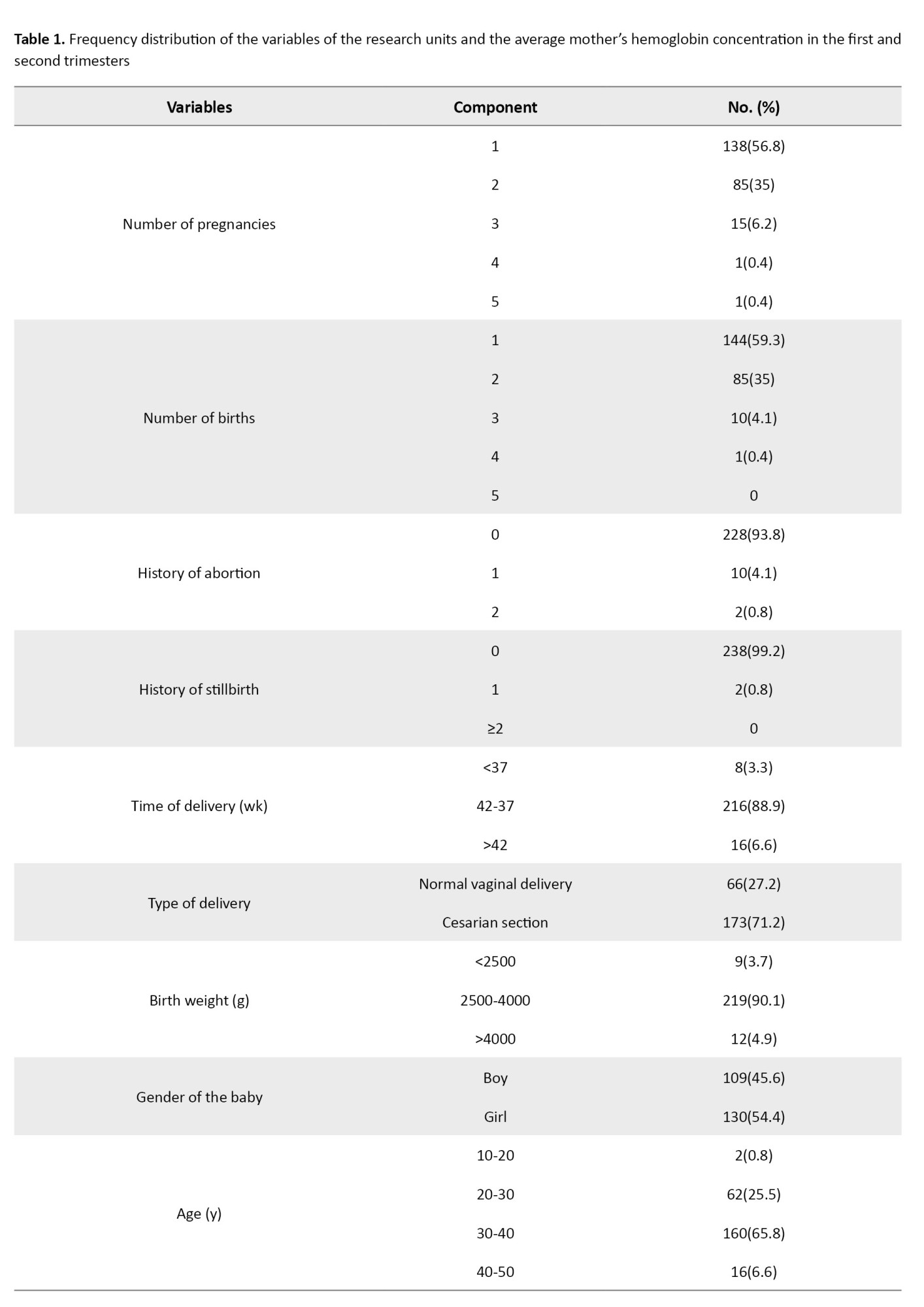

The average age of the research participants was 32.5±5.2 years, with a minimum of 19 and a maximum of 43. Also, 130 newborns (53.5%) had an average weight of 3353 g. Among the 240 pregnant women studied in the first trimester, 35(14.4%) and 97(40.4%) had anemia in the second trimester. The minimum and maximum hemoglobin concentration values were 9.2-14.5 mg/dL in the first trimester and 8.4-14.5 mg/dL in the second trimester (Table 1).

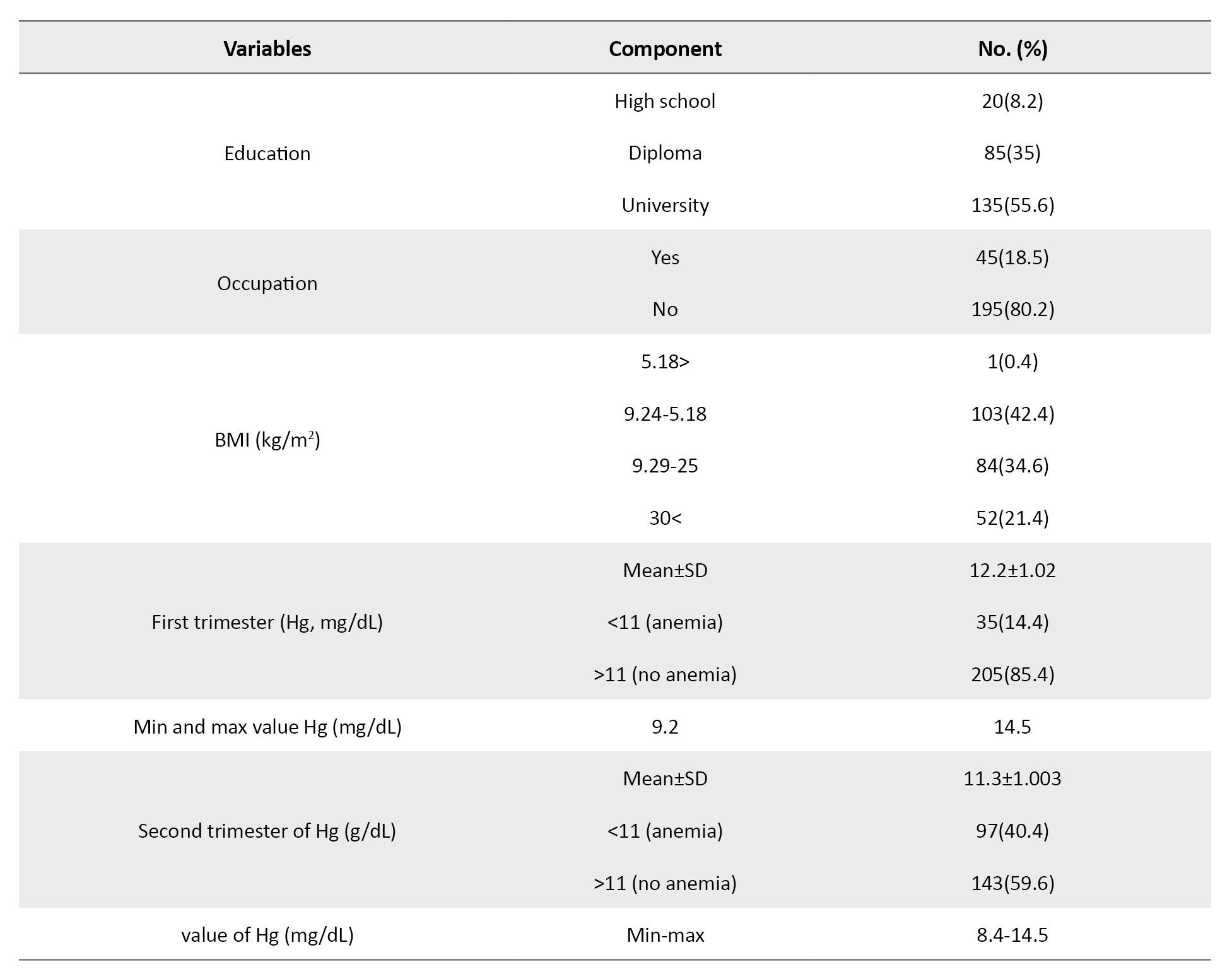

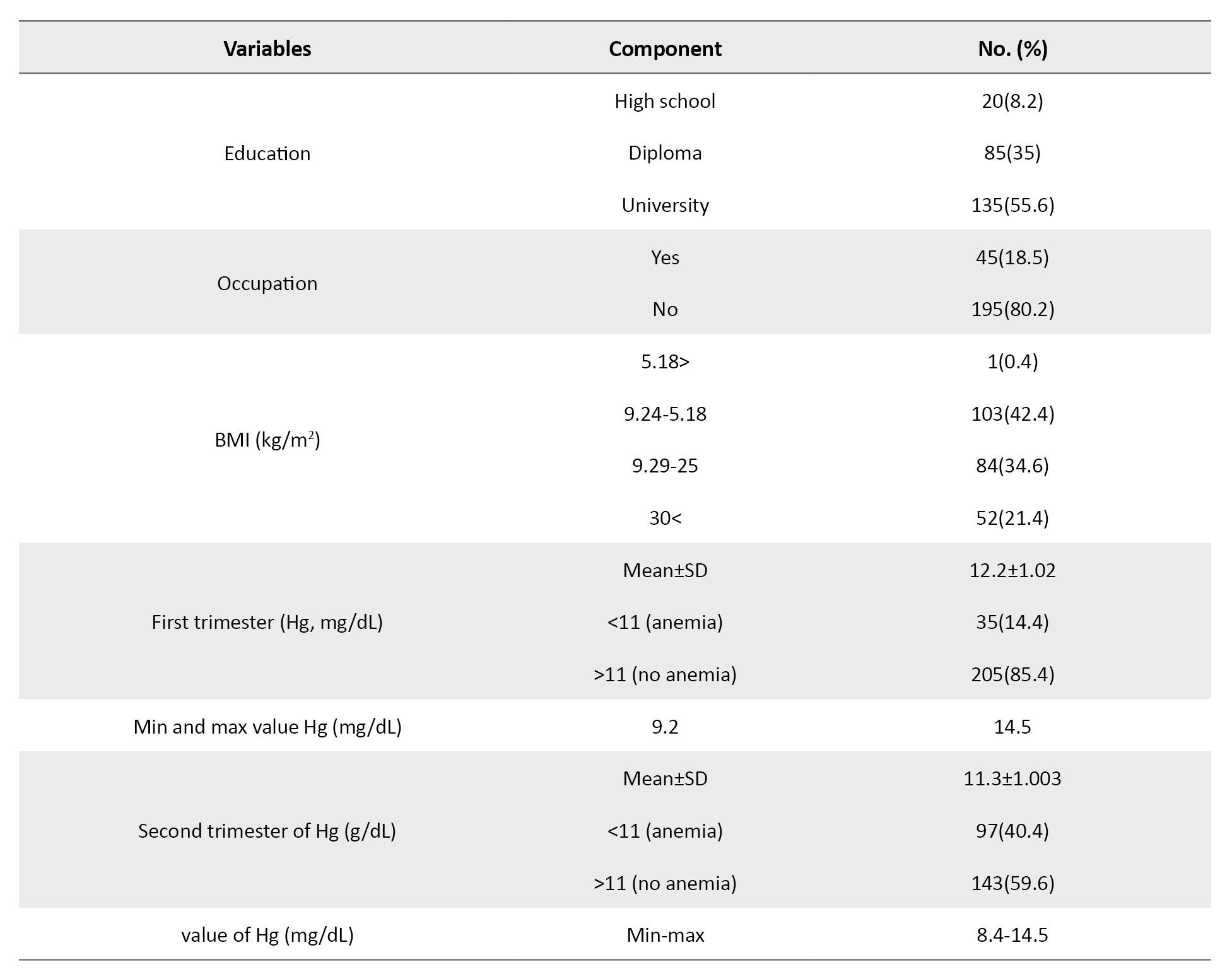

Among the studied variables, there was only a significant relationship between the number of pregnancies and BMI using the chi-square test (P<0.001) (Table 2).

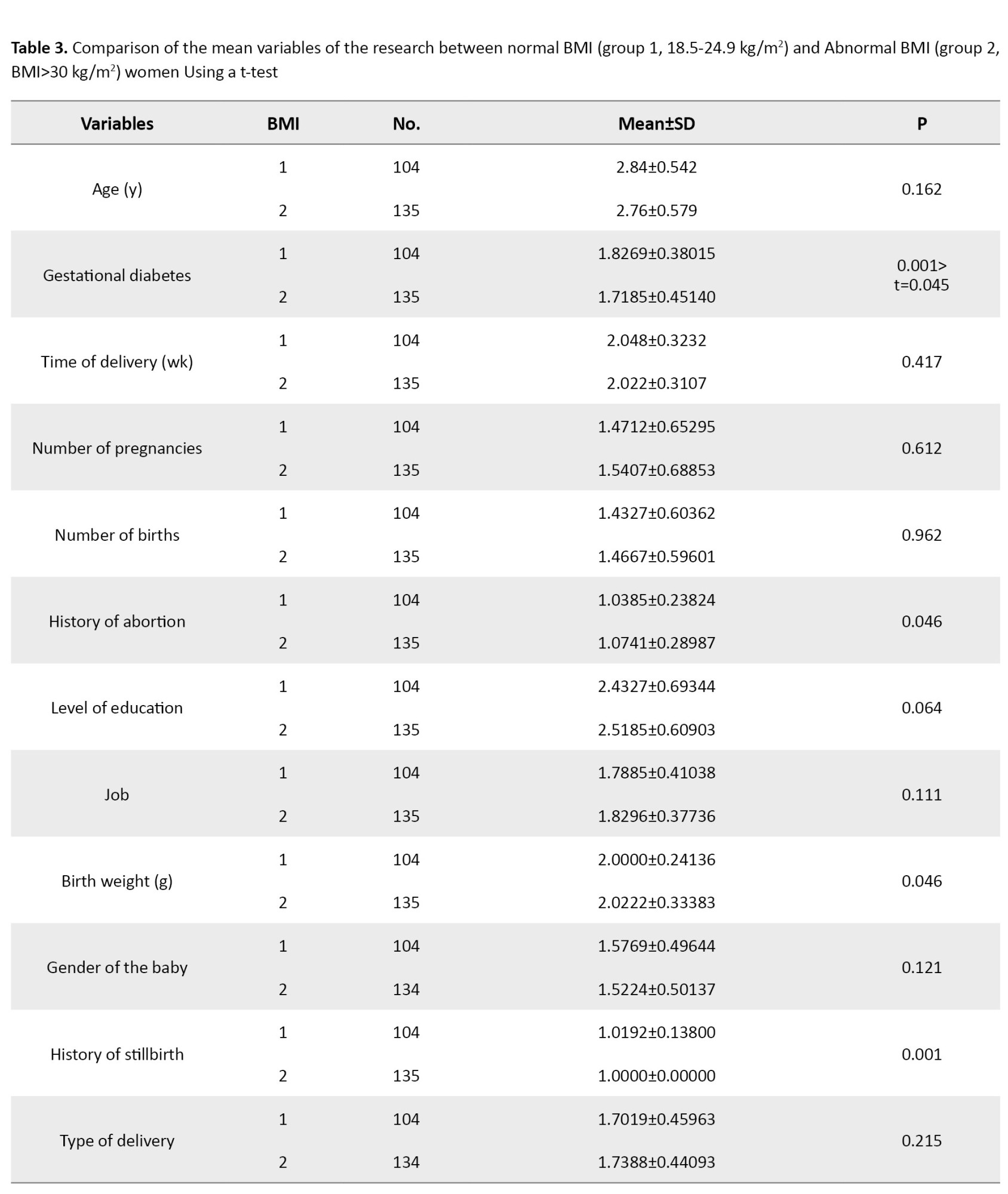

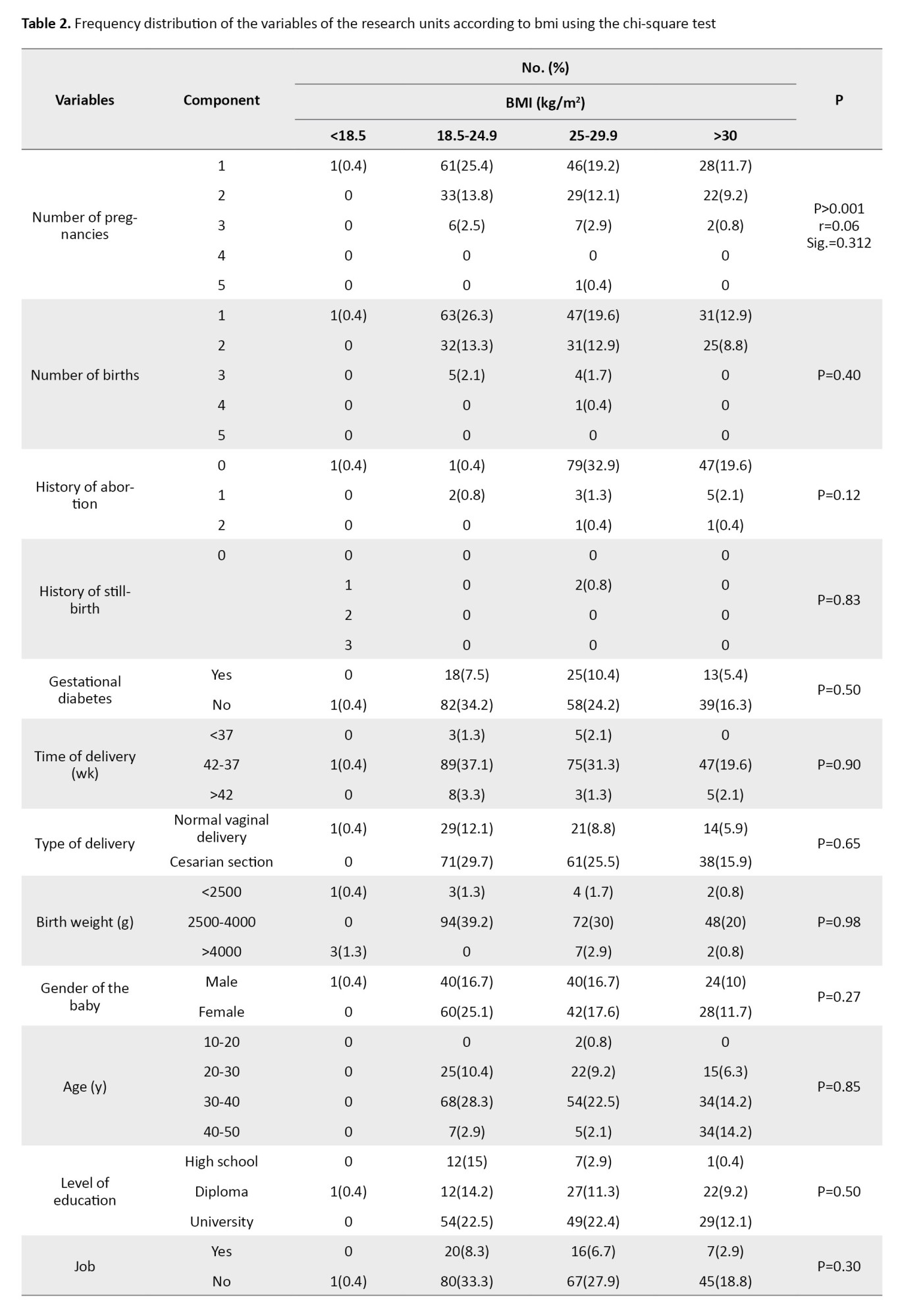

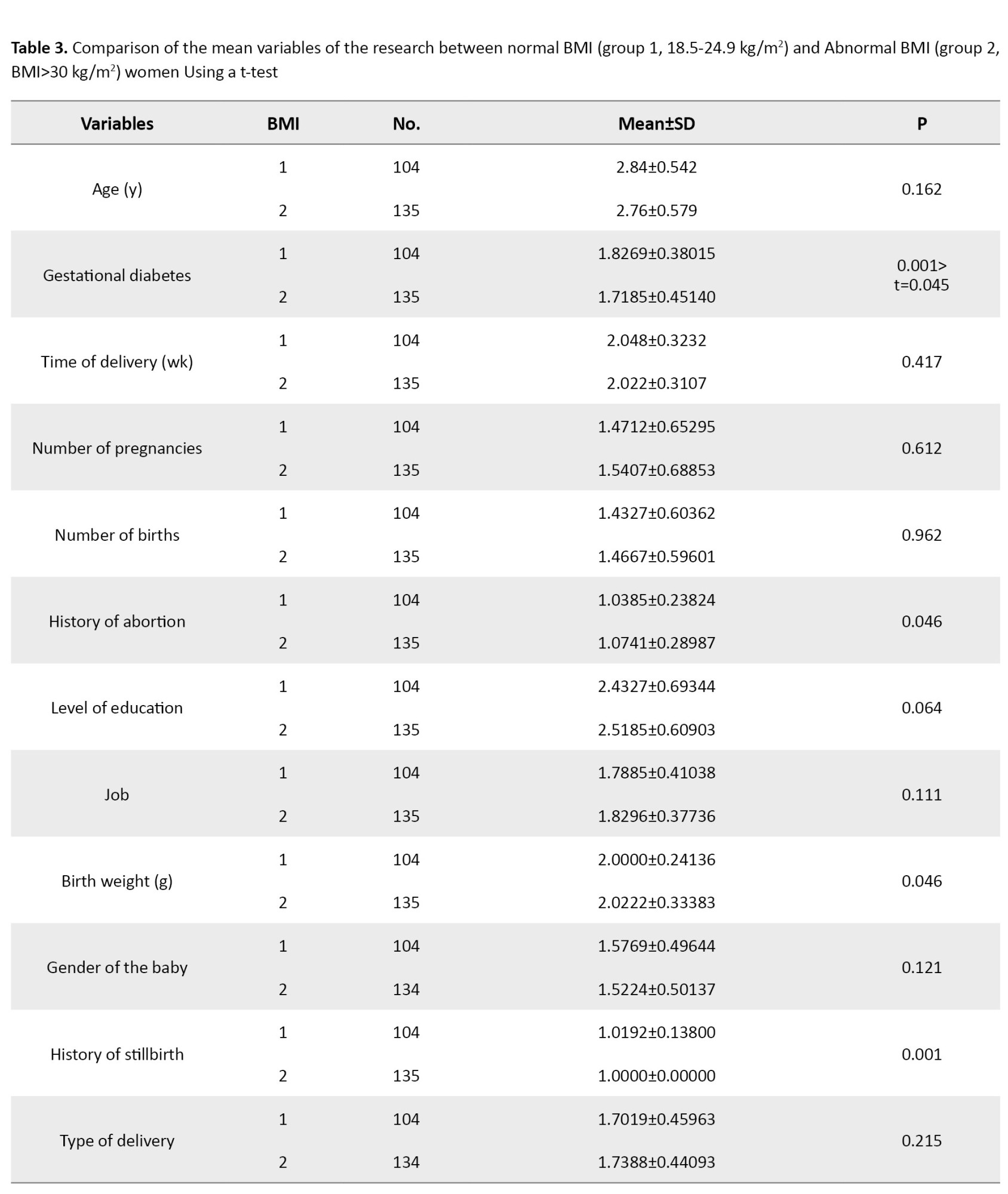

Comparison of the average of the research variables in two groups of women with normal and abnormal BMI showed significant relationships between a history of stillbirth (P=0.001), abortion (P=0.046), birth weight (P=0.046) and diabetes (P<0.001). Among the variables that had a significant relationship using the t-test between the two groups, only the relationship between gestational diabetes and BMI remained significant (P=0.045) (Table 3).

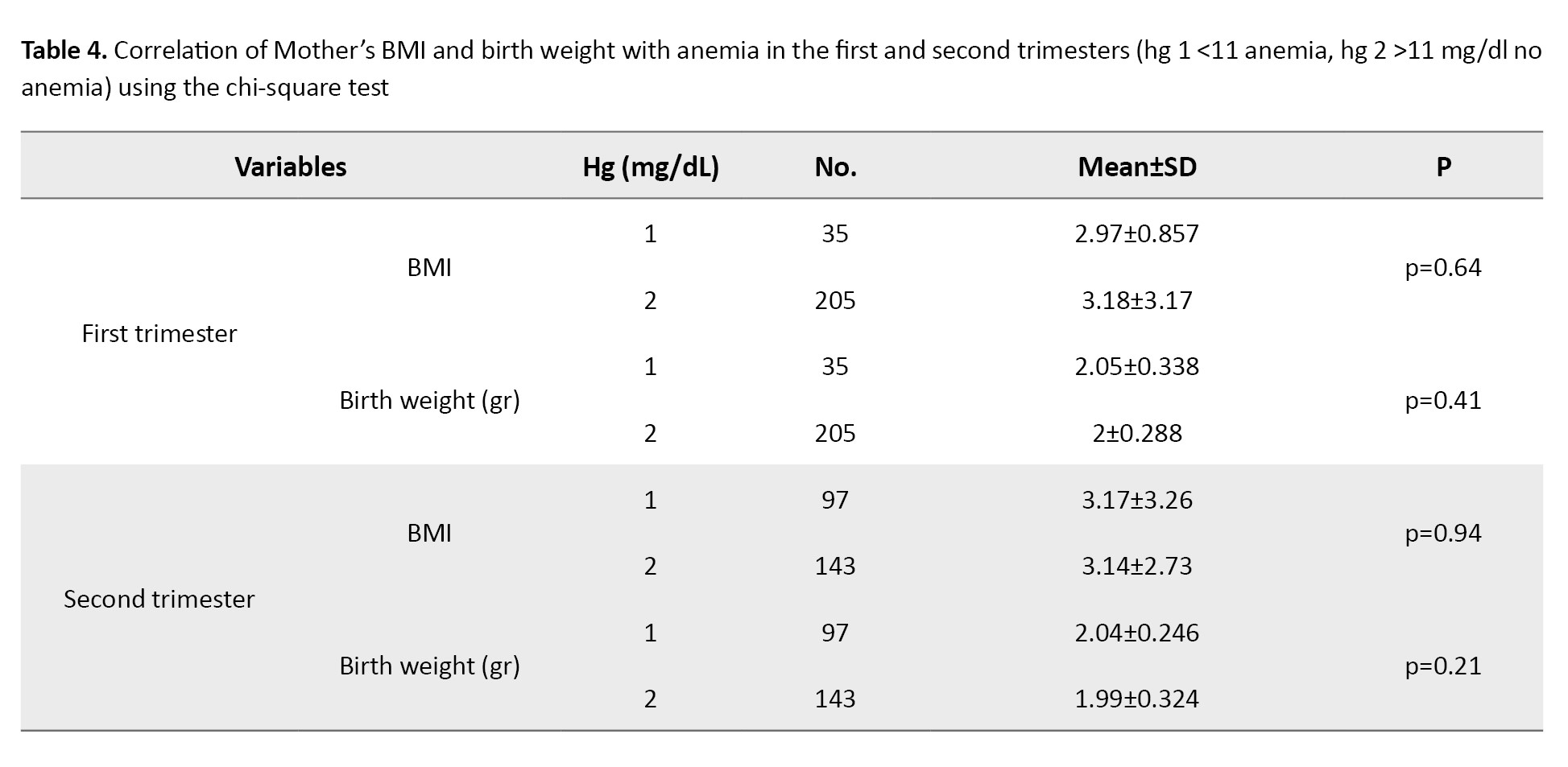

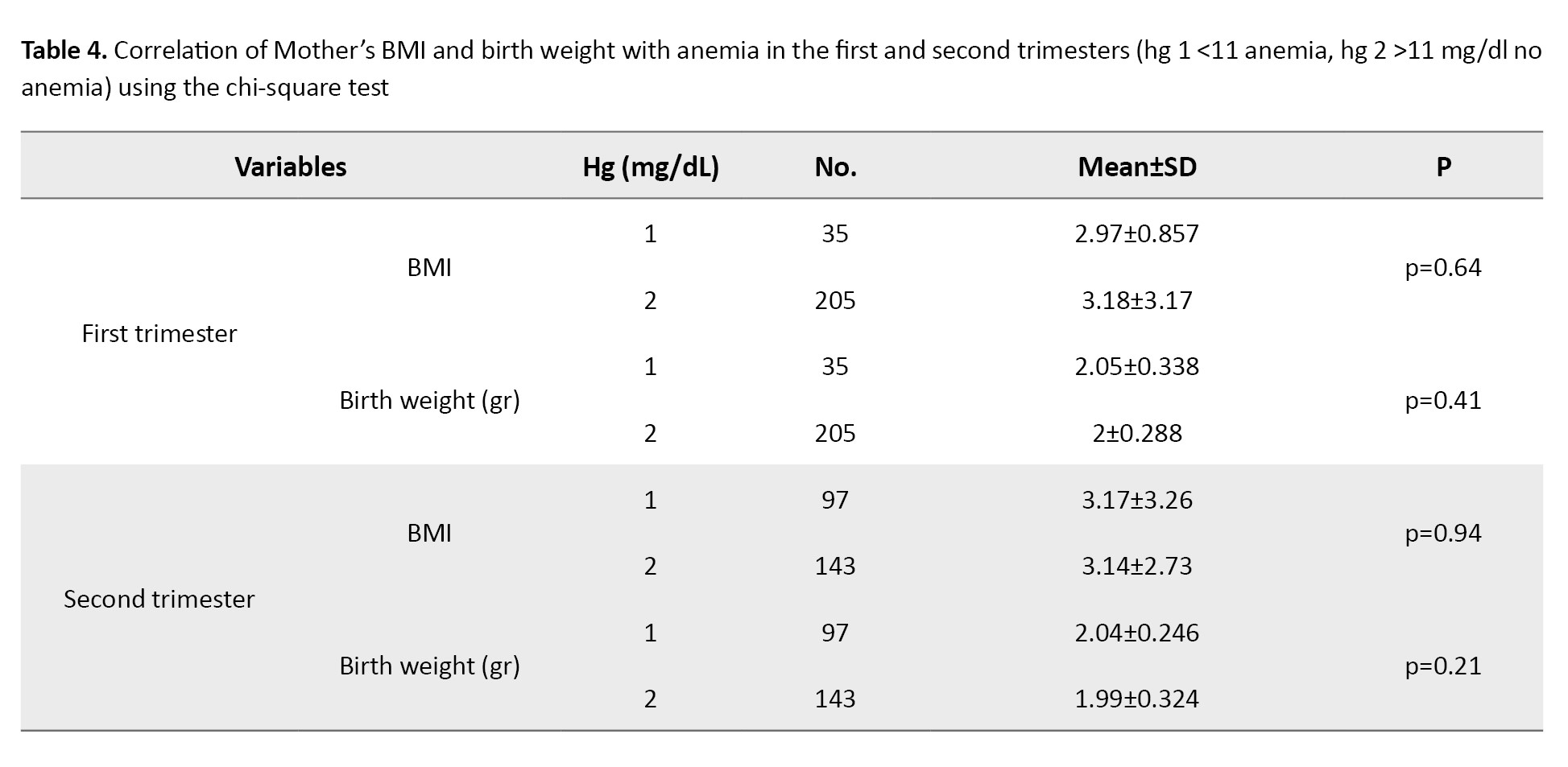

The results of the chi-square test showed no statistically significant difference between the mother’s BMI (P=0.61) and birth weight (P=0.55) in the first trimester and the mother’s BMI (P=0.57) and birth weight (P=0.18) in the second trimester with anemia (Table 4).

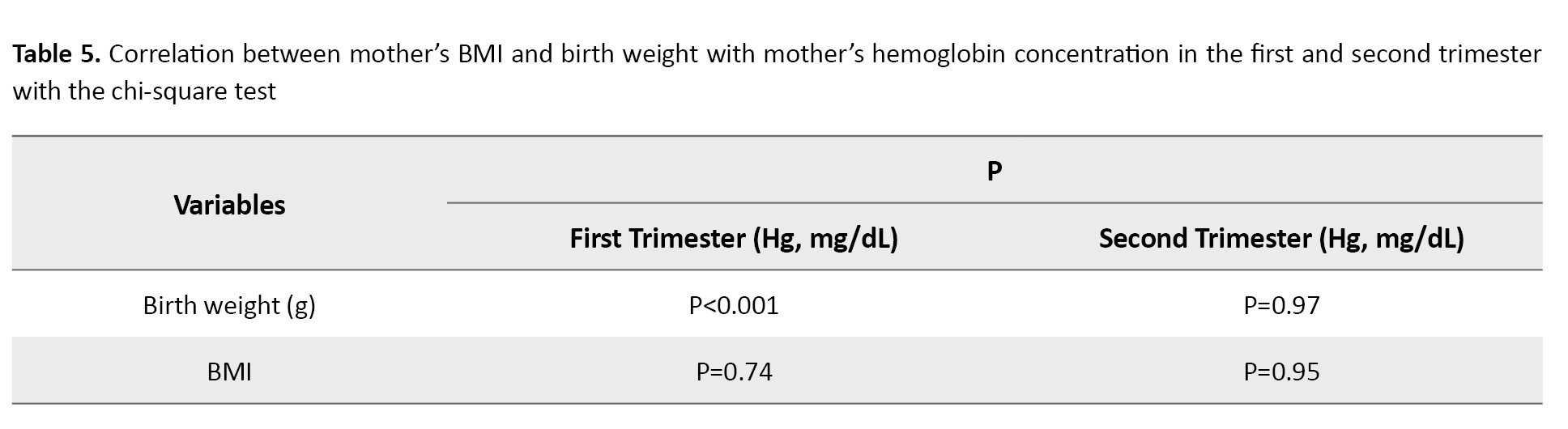

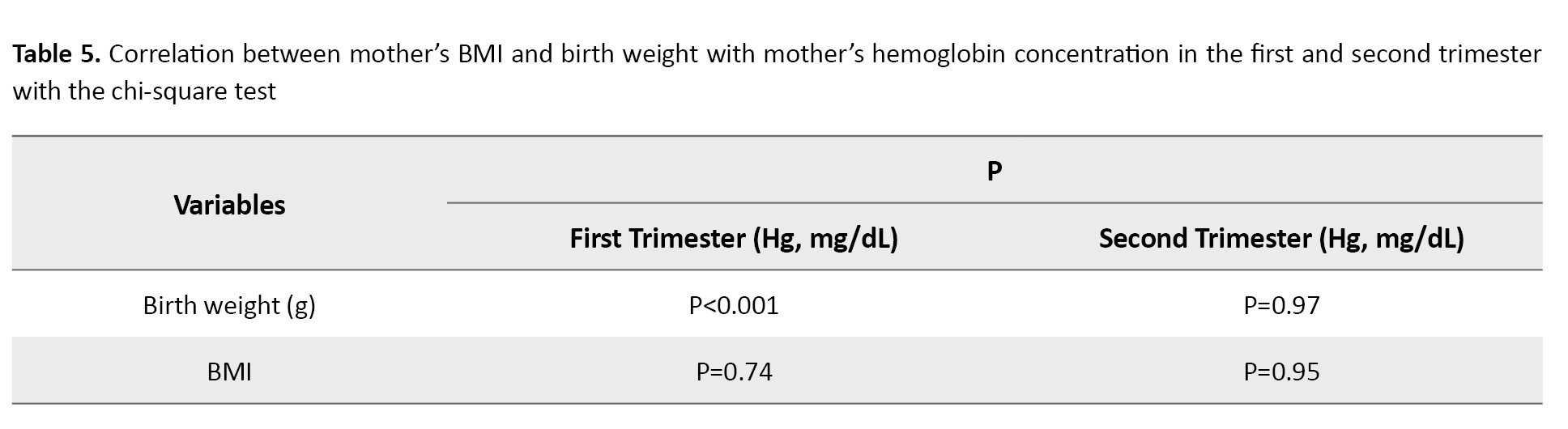

Examining the relationship between maternal BMI and birth weight with maternal hemoglobin concentration in the first and second trimesters showed a statistically significant difference only between birth weight and maternal hemoglobin concentration in the first trimester (P<0.001). There was no significant difference between maternal BMI and maternal hemoglobin concentration in the first and second trimesters and birth weight and maternal hemoglobin concentration in the second trimester (P<0.05 ) (Table 5).

Discussion

The present study aimed to determine the association between anemia and obesity with pregnancy and childbirth outcomes in pregnant women referred to comprehensive health service centers in Tonekabon City, Iran, in 2023. The results of the present study showed that 83 pregnant women (34.2%) were overweight, and 52 (21.4%) were obese. Also, among the variables studied, there was a statistically significant relationship between the number of pregnancies and BMI (using the chi-square test), consistent with the results of the study by Saeigarenaz et al. [6].

In the study by Moein et al., a statistically significant relationship was observed between the mother’s BMI at the beginning of pregnancy and the baby’s gender, low birth weight and gestational age [6]. Also, in the studies of Maleki et al. and Saeigarenaz et al. the relationship between the number of deliveries and BMI was significant [6, 32]. The results of the research of Shilpi and Satwanti [33] and Yang et al. also showed a significant relationship between the two variables of macrosomia and gestational diabetes with BMI, which was inconsistent with the present study results [33, 34]. The results of Sun et al. also showed a significant relationship between BMI and age, occupation and level of education, which was inconsistent with the results of the present study [35]. Comparison of the means of the variables under study in two groups of women with normal and obese weight showed a statistically significant relationship between the history of stillbirth, miscarriage, birth weight and gestational diabetes in two groups of women (P<0.05). The results of Simko et al. [8] research also showed that the incidence of complications such as macrosomia and gestational diabetes is higher in people with abnormal weight. The research of Alfadhli [7] found that obese women had a higher rate of gestational diabetes [7, 8]. In the study by Sun et al. women over 35 years of age and with a high BMI were 2.4 times more likely to develop gestational diabetes [35]. In line with the results of our study, Ke et al. [9] also showed a significant association between birth weight and diabetes with obesity [9]. In the study by Ahmadzadeh et al. the association between the two variables of obesity and type of delivery was significant, which was inconsistent with the present study results [10]. In the present study, 14.4% of pregnant women had anemia in the first trimester and 40.4% in the second trimester. In the study by Khalighi et al. anemia was estimated to be 24.1% among 737 pregnant women [36]. In the study of Vakili et al. the prevalence of anemia was estimated to be 4.5% in the first trimester and 4% in the second trimester [37]. Also, in the retrospective cohort study of Smith et al. with a sample size of 5151270 pregnant women, the prevalence of anemia was 12.8% (65906 women). In the study of Shi et al. which was conducted on 18948443 pregnant women with a mean age of 29.42 years, the prevalence of anemia was 17.7%. In the systematic study and meta-analysis of Karami et al., the prevalence of anemia in pregnant women was estimated to be 36.8% [22-24].

It seems that the differences in the natural physiological changes that occur during pregnancy in the volume of plasma and red blood cells according to each individual’s conditions, as well as the differences in the structure and social, cultural and economic status of different societies, including differences in income, knowledge, and attitudes of individuals towards health and prevention, nutritional status and eating habits, supplement consumption and ultimately lifestyle of individuals, can be pointed out in creating different results in different studies. In this study, the chi-square test result showed no statistically significant difference between maternal BMI and birth weight with anemia in the first and second trimesters (P<0.05). Also, comparing the mean maternal BMI and birth weight in two groups of anemic and non-anemic women in the first and second trimesters using the t-test was not significant. The study by Milani et al. showed a significant association between maternal BMI and anemia, which was inconsistent with the results of the present study. On the other hand, in this study, the association between anemia and birth weight was not significant, which was consistent with the results of the present study [38]. The results of some studies, such as Vakili et al. and Lashkardoost et al. also showed a lack of association between birth weight and anemia, consistent with the results of the present study [37, 39]. While in the study by Khalighi et al. the meta-analysis by Rahmati et al. the study by Jasim et al. and Ali et al. study, the association between birth weight and anemia was significant [27-29, 36]. Also, the relationship between maternal BMI and anemia in the study of Khalighi et al. was not significant [36]. Similar studies in Sudan and Khartoum have also shown the absence of a statistically significant difference between BMI and anemia. Also, Ezenweke et al. reported no straight relationship between BMI and hemoglobin level, which was in line with the results of the present study [40-42]. While the study of Vakili et al. [37] Motlagh et al. [12] and Eltayeb et al. showed a significant relationship between maternal BMI and anemia, which was inconsistent with the present study [11, 12, 37]. The present study showed a statistically significant difference between birth weight and maternal hemoglobin concentration in the first trimester. In the study of Afzal Aghai et al. [36] the relationship between maternal hemoglobin concentration and low birth weight was also significant. In this study, the probability of having a low birth-weight baby increased in mothers with high hemoglobin concentration compared to mothers with lower hemoglobin concentration, and this relationship was significant [36]. In the study of Ali et al. the relationship between hemoglobin level and birth weight was also significant [29].

This study showed a significant relationship between gestational diabetes, obesity, birth weight, and maternal hemoglobin concentration in the first trimester. Therefore, the health system can prioritize effective preventive programs, including providing policies, guidelines, and interventions, to increase awareness, knowledge, and attitudes of individuals at different levels to promote and improve a healthy lifestyle (paying attention to nutrition, regular exercise, having appropriate physical activity, and taking iron and folic acid supplements). In this case, the health of mothers and infants will increase and health and medical costs will decrease.

Conclusion

The results of this study showed that more than half of the women studied were overweight and obese. The prevalence of anemia was also high in Second trimester, which affected some pregnancy outcomes, including diabetes and birth weight. This issue requires the use of appropriate screening and intervention programs, including timely supplementation and a suitable lifestyle.

Limitations

Among the limitations of this research are its cross-sectional nature, the inability to generalize the study’s results to all geographical regions of Iran and the small sample size. Also, in some cases, the possibility of receiving incorrect information (excessive or underestimating the results) due to receiving information from pregnant women’s electronic health record system should be considered.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tonekabon Azad University, Tonekabon, Iran (Code: IRIAU.TONREC.1042009). Informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

Funding

The paper was extracted from the research project of Tayebeh Ramaji, approved by Tonekabon Azad University, Tonekabon, Iran.

Authors contributions

Study design, data collection and writing the original draft: Tayebeh Ramaji; Review, editing and final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors hereby express their gratitude and appreciation to the Research Vice-Chancellor of Tonekabon Azad University for approving the research project, to the health and treatment network of Tonekabon City for their cooperation in implementing the project and to the dear mothers.

References

Pregnancy is one of the most critical periods in the life of a mother and her child, and it is essential in terms of social health for the individual, family and society. The mother’s health during this period affects not only her quality of life but also the life and health of the fetus and future generations’ lives and health [1]. Obesity during pregnancy is one of the main worldwide health problems and it can lead to several adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes, such as gestational diabetes mellitus, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, labor induction, chorioamnionitis, and macrosomia [2, 3]. The World Health Organization (WHO) has considered body mass index (BMI) values above 25 and 30 as overweight and obese, respectively [4]. Based on research conducted in Iran in 2022 and 2017 and Saudi Arabia in 2021, the incidence of obesity and overweight among pregnant mothers was estimated to be 44.2%, 80.4%, and 47.8%, respectively [5, 6, 7]. According to some studies, obesity increases the risk of diabetes, fetal macrosomia, cesarean delivery and low birth weight, which are disturbing complications [8, 9, 10]. Some studies have also shown a relationship between maternal BMI and maternal anemia during pregnancy [11, 12].

Among the essential risks during pregnancy, iron deficiency anemia has been raised as one of the main nutritional and public health problems due to its high prevalence and adverse effects [13]. Anemia is the most prominent hematological manifestation during pregnancy and a dilemma of the WHO [14, 15]. Based on the definition of the WHO and the center for disease control, a hemoglobin concentration of <11 mg/dL in the first and third trimesters of pregnancy and less than 10.5 mg/dL in the second trimester of pregnancy is called gestational anemia [16-18]. Anemia is characterized by a decrease in hemoglobin, the number and volume of red blood cells and, as a result, a decrease in the capacity to carry oxygen in the blood circulation. Suppose dietary iron is not available to the body in sufficient quantity to generate red blood cells. In that case, the body first uses its reserves, and if iron deficiency continues, its reserves decrease and iron deficiency anemia occurs. The optimal concentration of hemoglobin required to respond to physiological needs differs according to age, gender, altitude of residence, smoking habits and pregnancy status [19, 20]. The prevalence of anemia in pregnancy varies significantly due to differences in social conditions, lifestyles and health behaviors in different cultures. Anemia can affect pregnant women all over the world [21].

In research in China and Canada, the prevalence of anemia in pregnant women was determined as 17.7% and 12.8%, respectively [22, 23]. In the meta-analysis of Karami et al., the prevalence of anemia in pregnant women was estimated as 36.8% [24]. Complications of gestational anemia in newborns include premature birth, low birth weight, neonatal anemia, growth delay and increased infant mortality. Maternal complications include an increased risk of postpartum infection, uterine inertia, increased maternal mortality rate and heart failure [25]. Various studies have also shown the relationship between anemia and complications such as low birth weight, preterm delivery, postpartum infection, and maternal mortality [26-28].

Given the increasing prevalence of obesity in pregnant women, as well as the importance of the effects of anemia and maternal weight before pregnancy on maternal and infant health during this period, the undesirable effects of obesity and anemia can be reduced by using simple preventive methods such as a healthy lifestyle (proper nutrition and exercise), appropriate diagnosis and treatment of anemia. Therefore, the present study was conducted to determine the relationship between anemia and obesity with pregnancy and childbirth outcomes in pregnant women referred to comprehensive health service centers in Tonekabon City, Iran, in 2023.

Material and Methods

Study design

This is a cross-sectional descriptive-analytical research.

Setting and participants

The research population comprised 240 women who gave birth between February and March 2022 and were postpartum. The sample size was estimated based on the prevalence of anemia research by Ali et al. using the Equation 1 with a confidence level of 95% and an error of 0.05 [29].

All samples had electronic health records in selected health centers. The inclusion criteria were all women who gave birth between 3 and 5 days before, had no chronic disease, did not use a special diet, had Iranian citizenship and lived in Tonekabon City, Iran. The exclusion criteria were unwillingness (referees to medical centers were invited to participate in the research through interviews; those willing gave the researcher access to the electronic health system by providing their national code) to participate in the research and multiple pregnancies.

Sample size and data collection

The authors presented the study to the city health network and obtained a letter of introduction. After referring to comprehensive urban health care centers and self-introductions, sufficient explanations about the topic, research objectives and how they would be implemented, the research was done in 2023. Further, assurances were made that the information on the research samples would remain confidential. Sampling was carried out using a multi-stage (stratified-cluster) method. Each of the comprehensive urban health care centers No. 3, 2, 1 and 4 of Tonekabon was considered a cluster, and the number of samples was proportional to the population covered by those centers (almost 4 centers had the same population covered). Based on the calculated sample size, 60 pregnant women were allocated to each cluster. Then, from each class, two centers (geographical area covered) were selected as clusters, and, considering the number of samples in each class, 30 pregnant women were selected from each center using a simple random method and entered the study.

The data collection tool is a checklist including personal and social characteristics (age, job, education level, height, weight, BMI at the beginning of pregnancy, less than 12 weeks), fertility history information (number of births, number of pregnancies, miscarriages, stillbirths), and information related to the consequences of pregnancy and childbirth (age pregnancy, type of delivery, gestational diabetes, sex of baby, birth weight). Scales and meters are valid tools for measuring weight and height. The reliability of the maternal scale with a standard weight of 2 kg, the reliability of the newborn scale with a standard weight of 500 g and the reliability of the meter with a standard wooden ruler were controlled and confirmed.

Blood tests (Hb, Hct) of the first trimester of pregnancy (6-10 weeks) and second trimester (16-20 weeks) were performed with a referral letter from pregnant women to a reference laboratory (Tonekabon County Health Center Laboratory), where the testing methods were the same. The device was calibrated every day by relevant experts.

It was extracted through the parsa (electronic health event file and referral) system by checking people’s electronic files. According to the WHO guidelines, pregnant women with hemoglobin less than 11 mg/dL were considered anemic [16, 17]. Anemic people were divided into three categories (severe anemia, less than 7; moderate, 7-10 and mild, 10-11 mg/dL) based on the hemoglobin concentration in the body [29 ,30].

Based on the WHO’s standard criteria, the women were categorized into 4 levels: Underweight (BMI less than 18.5 kg/m2), normal (18.5-24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25-29.9 kg/m2) and obese (more than 30 kg/m2) [31]. According to the WHO definition, a newborn weight below 2500 g is considered underweight. Then, the infant weight was divided into underweight, normal weight (2500-4000 g) and overweight (more than 4000 g). BMI was calculated by dividing weight (in kilograms) by the square of height (in meters). The mother’s weight was measured with light clothing using a standard scale and height using a standard meter mounted on the wall. The weight of the newborns at birth was also measured in the newborn ward without clothing using a standard scale for newborns in the supine position.

Statistical analysis

After collecting the data, they were analyzed using SPSS software, version 24. Descriptive statistics methods, central and dispersion indicators Mean±SD and frequency distribution were used to describe the characteristics of the research samples. To check the normality of the data, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used and to check the relationship of variables with anemia, the chi-square test (a significance level of zero means independence and no relationship between two variables) was used. An independent t-test was used to compare the average of two anemic and non-anemic groups with pregnancy outcomes. P<0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Sample description

The average age of the research participants was 32.5±5.2 years, with a minimum of 19 and a maximum of 43. Also, 130 newborns (53.5%) had an average weight of 3353 g. Among the 240 pregnant women studied in the first trimester, 35(14.4%) and 97(40.4%) had anemia in the second trimester. The minimum and maximum hemoglobin concentration values were 9.2-14.5 mg/dL in the first trimester and 8.4-14.5 mg/dL in the second trimester (Table 1).

Among the studied variables, there was only a significant relationship between the number of pregnancies and BMI using the chi-square test (P<0.001) (Table 2).

Comparison of the average of the research variables in two groups of women with normal and abnormal BMI showed significant relationships between a history of stillbirth (P=0.001), abortion (P=0.046), birth weight (P=0.046) and diabetes (P<0.001). Among the variables that had a significant relationship using the t-test between the two groups, only the relationship between gestational diabetes and BMI remained significant (P=0.045) (Table 3).

The results of the chi-square test showed no statistically significant difference between the mother’s BMI (P=0.61) and birth weight (P=0.55) in the first trimester and the mother’s BMI (P=0.57) and birth weight (P=0.18) in the second trimester with anemia (Table 4).

Examining the relationship between maternal BMI and birth weight with maternal hemoglobin concentration in the first and second trimesters showed a statistically significant difference only between birth weight and maternal hemoglobin concentration in the first trimester (P<0.001). There was no significant difference between maternal BMI and maternal hemoglobin concentration in the first and second trimesters and birth weight and maternal hemoglobin concentration in the second trimester (P<0.05 ) (Table 5).

Discussion

The present study aimed to determine the association between anemia and obesity with pregnancy and childbirth outcomes in pregnant women referred to comprehensive health service centers in Tonekabon City, Iran, in 2023. The results of the present study showed that 83 pregnant women (34.2%) were overweight, and 52 (21.4%) were obese. Also, among the variables studied, there was a statistically significant relationship between the number of pregnancies and BMI (using the chi-square test), consistent with the results of the study by Saeigarenaz et al. [6].

In the study by Moein et al., a statistically significant relationship was observed between the mother’s BMI at the beginning of pregnancy and the baby’s gender, low birth weight and gestational age [6]. Also, in the studies of Maleki et al. and Saeigarenaz et al. the relationship between the number of deliveries and BMI was significant [6, 32]. The results of the research of Shilpi and Satwanti [33] and Yang et al. also showed a significant relationship between the two variables of macrosomia and gestational diabetes with BMI, which was inconsistent with the present study results [33, 34]. The results of Sun et al. also showed a significant relationship between BMI and age, occupation and level of education, which was inconsistent with the results of the present study [35]. Comparison of the means of the variables under study in two groups of women with normal and obese weight showed a statistically significant relationship between the history of stillbirth, miscarriage, birth weight and gestational diabetes in two groups of women (P<0.05). The results of Simko et al. [8] research also showed that the incidence of complications such as macrosomia and gestational diabetes is higher in people with abnormal weight. The research of Alfadhli [7] found that obese women had a higher rate of gestational diabetes [7, 8]. In the study by Sun et al. women over 35 years of age and with a high BMI were 2.4 times more likely to develop gestational diabetes [35]. In line with the results of our study, Ke et al. [9] also showed a significant association between birth weight and diabetes with obesity [9]. In the study by Ahmadzadeh et al. the association between the two variables of obesity and type of delivery was significant, which was inconsistent with the present study results [10]. In the present study, 14.4% of pregnant women had anemia in the first trimester and 40.4% in the second trimester. In the study by Khalighi et al. anemia was estimated to be 24.1% among 737 pregnant women [36]. In the study of Vakili et al. the prevalence of anemia was estimated to be 4.5% in the first trimester and 4% in the second trimester [37]. Also, in the retrospective cohort study of Smith et al. with a sample size of 5151270 pregnant women, the prevalence of anemia was 12.8% (65906 women). In the study of Shi et al. which was conducted on 18948443 pregnant women with a mean age of 29.42 years, the prevalence of anemia was 17.7%. In the systematic study and meta-analysis of Karami et al., the prevalence of anemia in pregnant women was estimated to be 36.8% [22-24].

It seems that the differences in the natural physiological changes that occur during pregnancy in the volume of plasma and red blood cells according to each individual’s conditions, as well as the differences in the structure and social, cultural and economic status of different societies, including differences in income, knowledge, and attitudes of individuals towards health and prevention, nutritional status and eating habits, supplement consumption and ultimately lifestyle of individuals, can be pointed out in creating different results in different studies. In this study, the chi-square test result showed no statistically significant difference between maternal BMI and birth weight with anemia in the first and second trimesters (P<0.05). Also, comparing the mean maternal BMI and birth weight in two groups of anemic and non-anemic women in the first and second trimesters using the t-test was not significant. The study by Milani et al. showed a significant association between maternal BMI and anemia, which was inconsistent with the results of the present study. On the other hand, in this study, the association between anemia and birth weight was not significant, which was consistent with the results of the present study [38]. The results of some studies, such as Vakili et al. and Lashkardoost et al. also showed a lack of association between birth weight and anemia, consistent with the results of the present study [37, 39]. While in the study by Khalighi et al. the meta-analysis by Rahmati et al. the study by Jasim et al. and Ali et al. study, the association between birth weight and anemia was significant [27-29, 36]. Also, the relationship between maternal BMI and anemia in the study of Khalighi et al. was not significant [36]. Similar studies in Sudan and Khartoum have also shown the absence of a statistically significant difference between BMI and anemia. Also, Ezenweke et al. reported no straight relationship between BMI and hemoglobin level, which was in line with the results of the present study [40-42]. While the study of Vakili et al. [37] Motlagh et al. [12] and Eltayeb et al. showed a significant relationship between maternal BMI and anemia, which was inconsistent with the present study [11, 12, 37]. The present study showed a statistically significant difference between birth weight and maternal hemoglobin concentration in the first trimester. In the study of Afzal Aghai et al. [36] the relationship between maternal hemoglobin concentration and low birth weight was also significant. In this study, the probability of having a low birth-weight baby increased in mothers with high hemoglobin concentration compared to mothers with lower hemoglobin concentration, and this relationship was significant [36]. In the study of Ali et al. the relationship between hemoglobin level and birth weight was also significant [29].

This study showed a significant relationship between gestational diabetes, obesity, birth weight, and maternal hemoglobin concentration in the first trimester. Therefore, the health system can prioritize effective preventive programs, including providing policies, guidelines, and interventions, to increase awareness, knowledge, and attitudes of individuals at different levels to promote and improve a healthy lifestyle (paying attention to nutrition, regular exercise, having appropriate physical activity, and taking iron and folic acid supplements). In this case, the health of mothers and infants will increase and health and medical costs will decrease.

Conclusion

The results of this study showed that more than half of the women studied were overweight and obese. The prevalence of anemia was also high in Second trimester, which affected some pregnancy outcomes, including diabetes and birth weight. This issue requires the use of appropriate screening and intervention programs, including timely supplementation and a suitable lifestyle.

Limitations

Among the limitations of this research are its cross-sectional nature, the inability to generalize the study’s results to all geographical regions of Iran and the small sample size. Also, in some cases, the possibility of receiving incorrect information (excessive or underestimating the results) due to receiving information from pregnant women’s electronic health record system should be considered.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tonekabon Azad University, Tonekabon, Iran (Code: IRIAU.TONREC.1042009). Informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

Funding

The paper was extracted from the research project of Tayebeh Ramaji, approved by Tonekabon Azad University, Tonekabon, Iran.

Authors contributions

Study design, data collection and writing the original draft: Tayebeh Ramaji; Review, editing and final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors hereby express their gratitude and appreciation to the Research Vice-Chancellor of Tonekabon Azad University for approving the research project, to the health and treatment network of Tonekabon City for their cooperation in implementing the project and to the dear mothers.

References

- Akbari Z, Mansourian M, Kelishadi R. Relationship of the intake of different food groups by pregnant mothers with the birth weight and gestational age: Need for public and individual educational programs. Journal of Education and Health Promotion. 2015; 4:23. [DOI:10.4103/2277-9531.154109] [PMID]

- Wahabi, H, Esmaeil S, Fayed A. Maternal prepregnancy weight and pregnancy outcomes in Saudi Women: Subgroup analysis from Riyadh Mother and Baby Cohort Study (RAHMA). BioMed Research International. 2021; 2021:6655942. [DOI:10.1155/2021/6655942] [PMID]

- Fallatah AM, Babatin HM, Nassibi KM, Banweer MK, Fayoumi MN, Oraif AM. Maternal and neonatal outcomes among obese pregnant women in King Abdulaziz University Hospital: A retrospective single-center medical record review. Medical Archives. 2019; 73(6):425-32. [DOI:10.5455/medarh.2019.73.425-432] [PMID]

- Zehni K, Rokhzadi MZ. [Relationship between Body Mass Index with physical activity and some of demographic charecteristics among students in Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences (Persian)]. Scientific Journal of Nursing, Midwifery and Paramedical Faculty. 2017; 2(3):49 -57. [DOI:10.29252/sjnmp.2.3.6]

- Moeindarbari S, Forghani T, Sharif F. [The relationship between BMI and maternal weight gain during pregnancy with birth weight (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Infertility.2022; 25(6):12-20. [Link]

- Saeigarenaz M, Najarzadeh M. [The relationship between reproductive factors with a Body Mass Index In Women (Persian)]. Nursing and Midwifery Journal. 2017; 15(1):19-26. [Link]

- Alfadhli EM. Maternal obesity influences Birth Weight more than gestational Diabetes author. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2021; 21(1):111. [DOI:10.1186/s12884-021-03571-5] [PMID]

- Simko M, Totka A, Vondrova D, Samohyl M, Jurkovicova J, Trnka M, et al. Body Mass Index and gestational weight gain and their association with pregnancy complications and perinatal conditions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16:1751. [DOI:10.20944/preprints201904.0130.v1]

- Ke JF, Liu S, Ge RL, Ma L, Li MF. Associations of maternal pre-pregnancy BMI and gestational weight gain with the risks of adverse pregnancy outcomes in Chinese women with gestational diabetes mellitus. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2023; 23(1):414. [DOI:10.1186/s12884-023-05657-8] [PMID]

- Ahmadzadeh sani T, Peyman N, Esmaeili H. [The relationship between obesity and complications during pregnancy and childbirth in Dargaz: A cross sectional study(Persian)]. Journal of North Khorasan University of Medical sciences. 2016; 8(3):383-93. [DOI:10.18869/acadpub.jnkums.8.3.383]

- Eltayeb R, Binsaleh NK, Alsaif G, Ali RM, Alyahyawi AR, Adam I. Hemoglobin Levels, Anemia, and Their Associations with Body Mass Index among Pregnant Women in Hail Maternity Hospital, Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study. Nutrients. 2023; 15(16):3508. [DOI:10.3390/nu15163508] [PMID]

- Motlagh ME, Nasrollahpour Shirvani SD, Torkestani F, Hassanzadeh-Rostami Z, Rabiee SM, Ashrafian Amiri H, et al. The frequency of anemia and underlying factors among iranian pregnant women from provinces with different maternal mortality rate. Iranian Journal of Public Health. 2019; 48(2):338-44. [PMID]

- Haider BA, Olofin I, Wang M, Spiegelman D, Ezzati M, Fawzi WW, et al. Anaemia, prenatal iron use, and risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013; 346:f3443. [DOI:10.1136/bmj.f3443] [PMID]

- Sohail M, Shakeel S, Kumari S, Bharti A, Zahid F, Anwar S, et al. Prevalence of malaria infection and risk factors associated with anaemia among pregnant women in semiurban community of Hazaribag, Jharkhand, India. BioMed Research International. 2015; 2015:740512. [DOI:10.1155/2015/740512] [PMID]

- Lee AI, Okam MM. Anemia in pregnancy. Hematology/oncology Clinics of North America. 2011; 25(2):241-59. [DOI:10.1016/j.hoc.2011.02.001] [PMID]

- World Health Organization. the Global Prevalence of Anaemia in 2011. Geneva: WHO; 2011. [Link]

- Abdullahi H, Gasim GI, Saeed A, Imam AM, Adam I. Antenatal Iron and Folic Acid Supplementation Use by Pregnant Women in Khartoum, Sudan. BMC Research Notes. 2014; 7:498. [DOI:10.1186/1756-0500-7-498] [PMID]

- Gorgani F, Majlessi F, Momeni MK, Tol A, Foroshani AR. Prevalence of anemia and some related factor in pregnant woman referred to health centers affiliated to Zahedan University of Medical Sciences in 2013. Razi Journal of Medical Sciences. 2013; 22(141):47-58. [Link]

- Azami M, Darvishi Z, Sayehmiri K. Systematic review and meta-analysis of anemia among pregnant Iranian women (2005-2015). Shiraz E-Medical Journal. 2016; 17(4-5):e38462. [DOI:10.17795/semj38462]

- Benz EJ, Berliner N, Schiffman FJ. Anemia Pathophysiology diagnosis and management. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press;2018. [Link]

- Bora R, Sable C, Wolfson J, Boro K, Rao R. Prevalence of anemia in pregnant women and its effect on neonatal outcomes in Northeast India. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 2014; 27(9):887-91. [DOI:10.3109/14767058.2013.845161] [PMID]

- Shi H, Chen L, Wang Y, Sun M, Guo Y, Ma S, et al. Severity of anemia during pregnancy and adverse maternal and fetal outcomes. JAMA Network Open. 2022; 5(2):e2147046. [DOI:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.47046] [PMID]

- Smith C, Teng F, Branch E, Chu S, Joseph KS. Maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality associated with anemia in pregnancy. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2019; 134(6):1234-44. [DOI:10.1097/AOG.0000000000003557] [PMID]

- Karami M, Chaleshgar M, Salari N, Akbari H, Mohammad M. Global prevalence of Anemia in pregnant women: A comprehensive systematic review and meta analysis. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2022; 26(7):1473-87. [DOI:10.1007/s10995-022-03450-1] [PMID]

- Akbarzadeh M, Tabatabaee H, Ramzi M. Comparison of the prevalence of anemia in the first, second and third trimester of pregnancy in a medical and educational center in Shiraz. Scientific Journal of Iranian Blood Transfusion Organization. 2011; 8(3):1. [Link]

- Johnson A, Vaithilingan S, Avudaiappan S. The Interplay of Hypertension and Anemia on Pregnancy Outcomes. Cureus. 2023. 15(10):e46390. [DOI:10.7759/cureus.46390]

- Rahmati S, Azami M, Badfar G, Parizad N, Sayehmiri K. The relationship between maternal anemia during pregnancy with preterm birth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 2020; 33(15):2679-89. [DOI:10.1080/14767058.2018.1555811] [PMID]

- Jasim SK, Al-Momen H, Al-Asadi F. Maternal anemia prevalence and subsequent neonatal complications in Iraq. Open Access Macedonian Journal of Medical Sciences. 2020; 8(B):71-5. [Link]

- Ali HJ, Ezzaddin SA. Anemia in Pregnancy and its Association with Low Birth Weight in Sulaimani Primary Health Care Centers. University of Thi-Qar Journal of Medicine. 2023; 26(2):94-105. [Link]

- Mahmoudi G, Nick Pour B, Khazaee-Pool M, Majlessi F. [The study of anemia prevalence and some related factors among pregnant women in health centers of Mazanderan in 2015 (Persian)]. Journal of Payavard Salamat. 2017; 11(3):266-75. [Link]

- Seidell JC, Halberstadt J. The global burden of obesity and the challenges of prevention. Annals of Nutrition & Metabolism. 2015; 66( Suppl 2):7-12. [PMID]

- Maleki Z, Dehghani S, Mobasheri F. [The relationship between maternal weight gain during pregnancy and birth weight in patients referred to the gynecology and obstetrics ward (Persian)]. Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2020; 7(2):1- 10. [DOI:10.29252/jpm.7.2.1]

- Shilpi G, Satwanti K. Independent and combined association of parity and short pregnancy with obesity and weight change among Indian women. Health. 2012; 4(5):271-6. [DOI:10.4236/health.2012.45044]

- Yang W, Han F, Gao X, Chen Y, Ji L, Cai X. Relationship between gestational weight gain and pregnancy complications or delivery outcome. Scientific Reports. 2017; 7(1):12531. [DOI:10.1038/s41598-017-12921-3] [PMID]

- Sun Y, Shen Z, Zhan Y, Wang Y, Ma S, Zhang S, et al. Effects of pre-pregnancy body mass index and gestational weight gain on maternal and infant complications. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2020; 20(1):390. [DOI:10.1186/s12884-020-03071-y] [PMID]

- Afzal Aghai M, Musa Farkhani E, Beygi B, Eftekhari Gol R, Eslami V, Bahrami HR. [Maternal Anemia during pregnancy and birth outcomes: a population based cross sectional study Maternal Anemia and birth outcomes (Persian)]. Journal of Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences. 2021; 28(1):124-32. [Link]

- Vakili M, Mardani Z, Mirzaei M. [Frequency of Anemia in the Pregnant Women Referring to the Health Centers in Yazd, Iran (2016-2017) (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Infertility. 2018; 21(2):9-15. [DOI:10.22038/ijogi.2018.10701]

- Milani F, Motamed B, Salamt F, Ghodsi Khorsand SM. [Comparison of post- delivery maternal and fetal complication among anemia and non anemia women(Persian)]. Journal of Guilan University of Medical Sciences. 2016; 25(97):61-8. [Link]

- Lashkardoost H, Mohammad Doust H, Saadati H, Nazari Z, Sanayee Joshaghan M, Andishe Hamedi. Prevalence of Hemoglobin Anemia among Pregnant Women in the Northeast of Iran. Journal of Community Health Research. 2019; 8(2):121-8. [Link]

- Ezenweke CP, Adeniyi IA, Yahya WB, Onoja RE. Determinants and spatial patterns of anaemia and haemoglobin concentration among pregnant women in Nigeria using structured additive regression models. Spatial and Spatio-Temporal Epidemiology. 2023; 45:100578. [DOI:10.1016/j.sste.2023.100578] [PMID]

- Eltayeb R, Rayis DA, Sharif ME, Ahmed ABA, Elhardello O, Adam I. The prevalence of serum magnesium and iron deficiency anaemia among Sudanese women in early pregnancy: A cross-sectional study. Transactions of The Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2019, 113(1):31-5. [DOI:10.1093/trstmh/try109] [PMID]

- Mubarak N, Gasim GI, Khalafalla KE, Ali NI, Adam I. Helicobacter pylori, anemia, iron deficiency and thrombocytopenia among pregnant women at Khartoum, Sudan. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2014; 108(6):380-4. [DOI:10.1093/trstmh/tru044] [PMID]

Type of Study: Original Article |

Subject:

Midwifery

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |