Volume 12, Issue 3 (Summer 2024)

Iran J Health Sci 2024, 12(3): 223-230 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: IR.QUMS.REC.1400.359

Clinical trials code: 0

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Emrani R, Akhoundi M. Investigating Psychosocial Causes of the Tendency for Rhinoplasty in Qazvin City, Iran, in 2023: A Descriptive Analytical Study. Iran J Health Sci 2024; 12 (3) :223-230

URL: http://jhs.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-895-en.html

URL: http://jhs.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-895-en.html

Dental Caries Prevention Research Center, Qazvin University of Medical Sciences, Qazvin, Iran. , Rezaemrani@yahoo.com

Full-Text [PDF 645 kb]

(432 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1358 Views)

Full-Text: (409 Views)

Introduction

Cosmetic surgery is a procedure not because of medical needs but primarily to create beauty. Rhinoplasty is a challenging procedure in plastic surgery because it entails many unnecessary demands. The request for rhinoplasty is rising, and it is one of the top five surgical cosmetic procedures worldwide. Cosmetic rhinoplasty is a surgery used to change the nose’s appearance to look more beautiful. The big difference between general rhinoplasty and cosmetic rhinoplasty lies in an individual’s demand to change the shape of the nose for more satisfaction, which is generally based on social or psychological demands [1, 2].

Combining aesthetics and cosmetic procedures with technological and medical advancements has transformed beauty from an entirely natural and inconvertible concept to an accessible process, primarily through some medical surgery, including rhinoplasty [3]. Consequently, beauty has become more accessible to everyone in these days. Iran is one of the countries with a high demand for cosmetic rhinoplasty worldwide. One percent of the world’s population belongs to Iran, but 5% of the world’s beauty surgeries are performed in Iran. The inclination toward various cosmetic surgeries has increased worldwide; for example, millions of cosmetic surgeries are performed annually in the United States [4, 5].

In some parts of the world, cosmetic surgery is becoming more popular because it is recognized as a social fashion, and maybe this phenomenon is more influenced by the pressure of media, especially the Internet and social networks [6].

Rhinoplasty aims to improve patients’ quality of life (QoL) and self-satisfaction with their appearance. Successful rhinoplasty procedures typically enhance people’s QoL regarding their physical health, self-confidence, and satisfaction [7, 8].

It is of medical interest to evaluate the psychosocial functioning of volunteers for rhinoplasty and identify their psychological effects. Understanding the psychological factors that create demand for this procedure is very important, considering that cosmetic surgery has a high cost, lacks insurance coverage, and has minimal impact on physical health. In addition, it should be remembered that rhinoplasty has its risks. Many surgeons claim that almost all cosmetic surgeries, including rhinoplasty, have side effects, and practically, many of them are irreversible. These effects include the psychological and even social harm brought on by unsuccessful procedures, such as anxiety and obsession. As a result, finding candidates for surgery who lack the necessary psychological stability is always of interest to surgeons. Also, knowing the psychological factors affecting surgical candidates is of high value for surgeons and doctors [9, 10, 11, 12].

Considering the increasing demand for cosmetic surgery and the importance of knowing people’s psychological structures, this study was performed in Qazvin, Iran, in 2022. The results of this research can be effective in using methods to prevent unnecessary cosmetic surgeries because performing unnecessary surgeries can cause mental stress for the individual, waste money in society, and produce unrealistic needs in health. This study aimed to evaluate different determinants of the patient’s psychosocial functioning that might affect the outcome of rhinoplasty surgery.

Materials and Methods

In this case-control study, 228 volunteers participated in a special hospital for rhinoplasty in Qazvin in 2022. The study’s sample size was estimated at a minimum of 81 according to similar studies and based on the formula of case-control studies (α=0.05, β=0.20).

The inclusion criteria were single women who voluntarily applied for rhinoplasty treatment without therapeutic indication and have a friend who is the same as her in terms of age, gender, education, and level of income but who does not request rhinoplasty, lacks a history of specific mental disorders (self-express), is Iranian, and can speak Persian. To match the cultural and, to some extent, genetic factors, all selected participants in this study were only from the permanent residence of Qazvin. All samples were chosen from volunteers who had applied to a particular hospital for rhinoplasty.

After the volunteers entered the study, we reviewed their files to ensure that the surgery was done only for cosmetic purposes and not for medical needs. The study objectives and method were described for the volunteers, and informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study questionnaire was completed during a face-to-face meeting.

After designing the questionnaire to assess its validity, the questions were evaluated by experts in cosmetic surgery and psychology (two psychologists, two oral and maxillofacial surgeons, one medical doctor, three specialist dentists, and one faculty member). The content validity index (CVI=0.74) and content validity ratio (CVR=0.59) of the items were validated, and to determine the reliability of the questionnaire, the coefficient of reliability (Cronbach α) was calculated. For this purpose, the questionnaire was provided to 22 persons in the study population. Finally, the reliability coefficient for this questionnaire was estimated at 0.83.

The data collection tool was a research-made questionnaire containing 3 parts. The first part comprised demographic questions, including age, job, marital status, and level of education. The second part was on the psychosocial causes of the tendency for cosmetic rhinoplasty, a researcher-made questionnaire consisting of 9 questions. It was based on a 3-point scale (agree, no idea, disagree). Therefore, choosing “agree” indicated the greater effect of psychosocial factors on the tendency for rhinoplasty.

The third tool used in this research was the NEO-FFI (Neo-five factor inventory) questionnaire. NEO-FFI questionnaire has 60 questions that assess the five personality traits of “openness,” “agreeableness,” “nervousness,” “conscientiousness,” and “extroversion.” This test has been standardized in many studies and used in Iran. Also, the Cronbach α of this questionnaire was about 0.77 [13].

In this 5-option questionnaire, scoring was done from 0 to 4, with “completely disagree” to “agree” options, and each part had a minimum of 0 and a maximum of 60 marks. The entire questionnaire had a scale between 0 and 240. The questionnaires were completed before the surgery, the volunteers answered them, and the researcher was there to help them in case of ambiguity. The demographic information of volunteers was also obtained. The descriptive statistics and inferential statistics, including analysis of variance to compare multiple groups (age, level of study, and job), and the t-test to compare between two groups (case-control) were performed. The level of significance was set at P>0.05. Analysis was done by using SPSS software, version 25.

Results

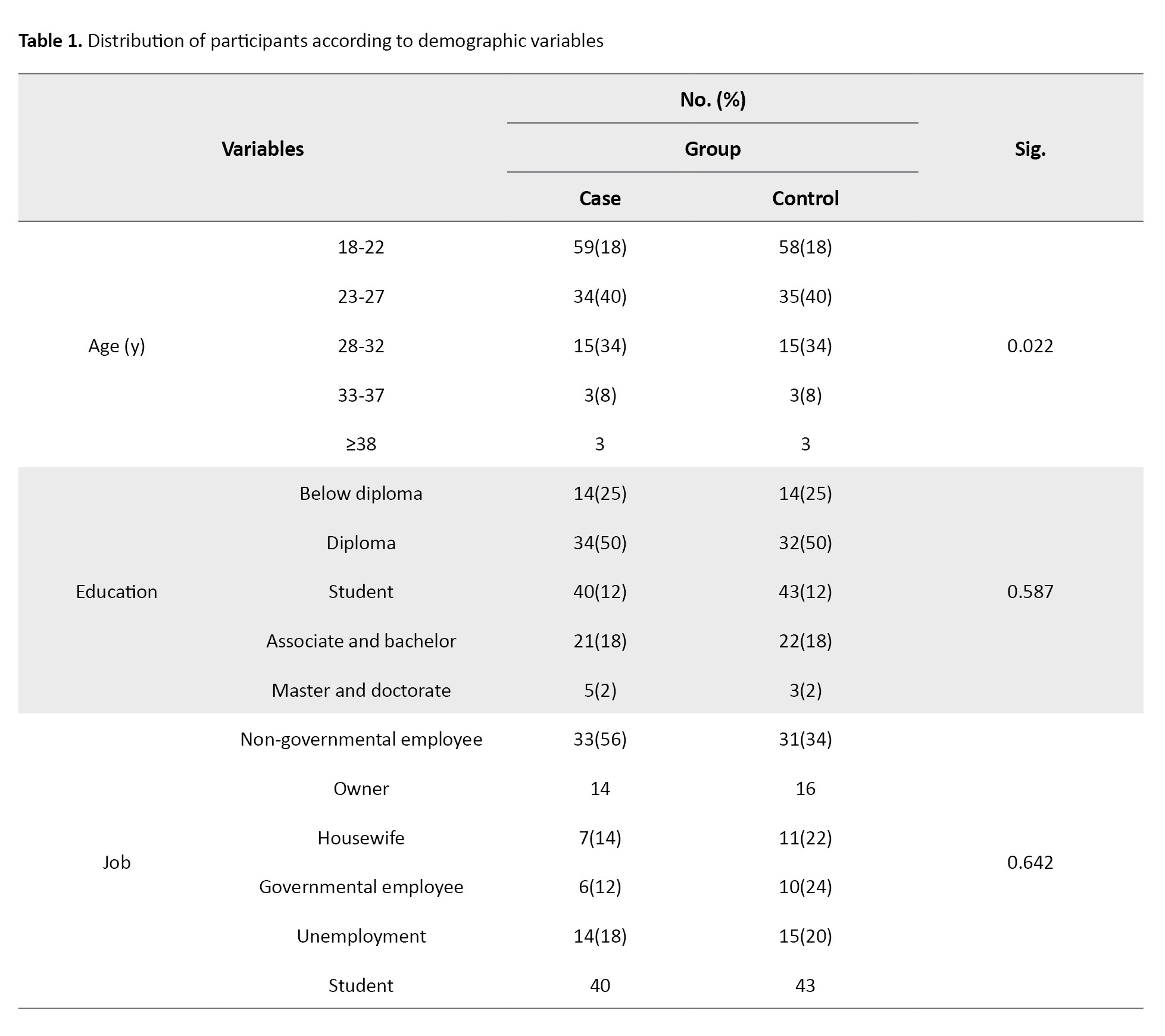

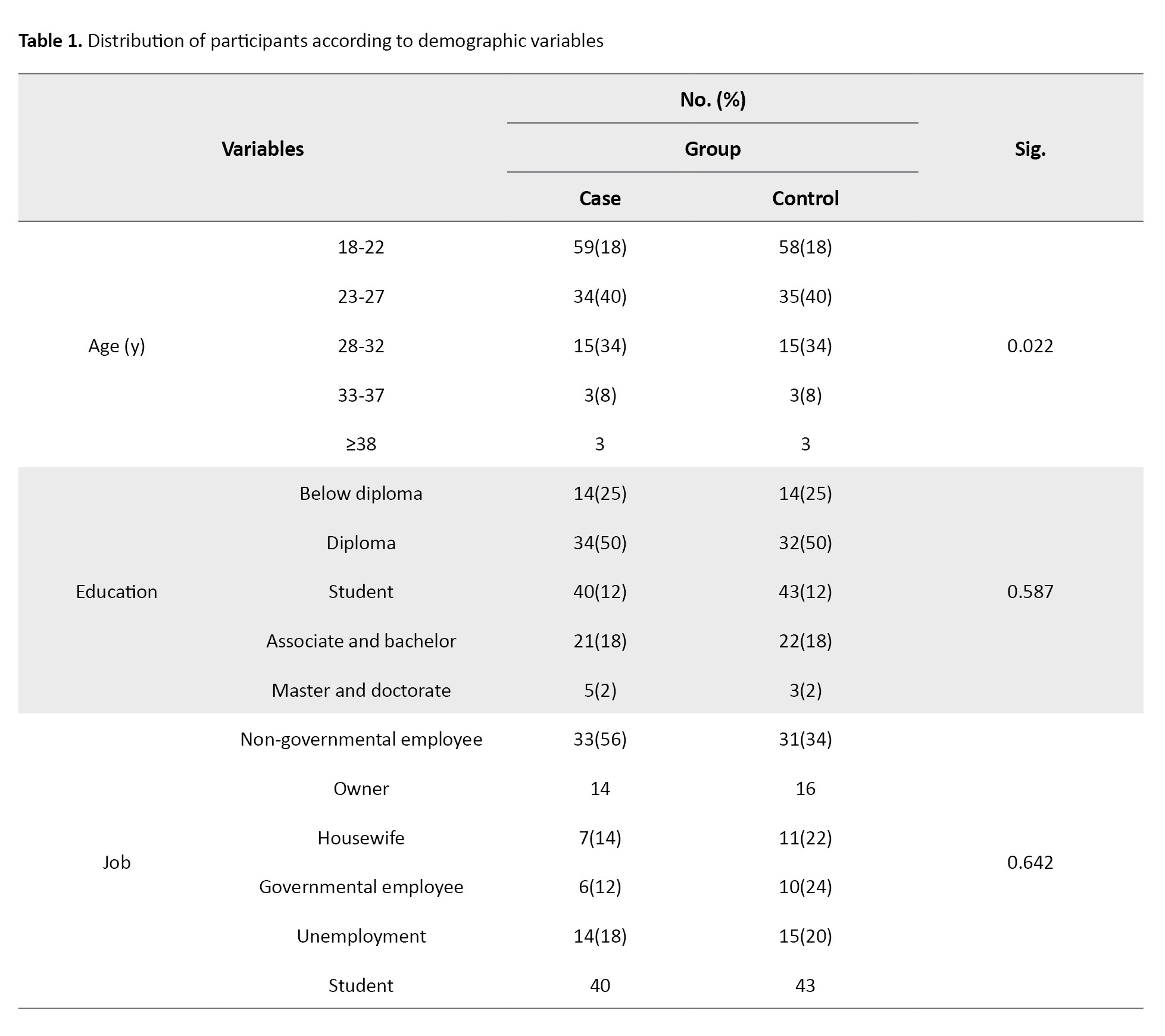

Two hundred twenty-eight volunteers participated in this study (114 cases, 114 controls). Age, job, and level of education were considered as variables in the mean score of variables in two groups (case and control) to compare the effect of these variables. The Mean±SD age of the participants was 24.6±3.6 years (case, 24.2; control, 25). All subjects were single. Finally, in terms of academic status, students were the most (case, 43; control, 40) group followed by those having diploma (cases, 34; control, 32). The highest frequency according to job category belonged to the students (cases 43, control 40) group, followed by the non-governmental employee group (case, 33; control, 31) (Table 1).

There were no significant differences among participants in terms of job and level of education. Analysis of variance was used to compare between groups (only on the case group).

Regarding the social causes of the tendency for cosmetic procedure, “rhinoplasty improves self-confidence (101[88.5%]),” “rhinoplasty improves beauty (97[85%])” and “peer pressure” (86[74.5%]) were the most frequent response of the participants and rhinoplasty is fashionable had least frequency (42[36.8%]) response.

According to the results, the participants’ answers in the case and control groups on the “peer pressure” and “it’s a new experience in life” were not significant. There were differences in other domains between case and control groups, and the differences were significant. All results are presented in Table 2.

According to the result of the Neo test, three domains (openness, extraversion, and agreeableness) were higher and more significant in the case group. Neuroticism was higher in the case group but was not significant. Conscientiousness was significantly higher in the control group (Table 3).

Discussion

The present study was designed to investigate the psychosocial reasons for taking cosmetic rhinoplasty surgery in patients referred to hospitals in Qazvin. The results showed a significant difference between the attitudes of volunteers and non-volunteers regarding rhinoplasty and their psychological characteristics.

Many participants agreed that “self-confidence” was an important psychological factor in performing rhinoplasty and was the most frequently “agree” answer among all domains. This domain referred to the participants’ tendency to appear better in society. With this result, some articles have shown the effect of a lack of self-confidence in performing cosmetic surgery and reported that people with low self-confidence are more seriously faced with the acceptance of others [15].

Also, concentrating on the beauty of the face and peer pressure were in second and third place among the psychosocial factors in performing rhinoplasty. Beauty is essential for women, and we must know that we have a world where physical appearance seems to rule over many social features. These articles also state that women undergo cosmetic surgery as a means of gaining power because beauty is accompanied by power. Beauty enables women to benefit from unequal opportunities in society. Peer pressure is a pivotal determinant factor in making decisions, including cosmetic procedures. Some studies approved the effect of peer pressure on deciding on cosmetic procedures [16-20, 25]. The domain “impact on the opposite gender” also had a higher score in the present study. Many studies showed that women have more emotional tendencies than men, and their attractiveness is necessary for the opposite gender [21, 22]. The issue of “new experience in my life” and internet pressure was also raised in one of the questions with higher positive answers. A study in Saudi Arabia showed that media, including social networks, greatly impacted people in our time. Reviewing cosmetic surgery-related materials on the internet and spending more time on social media are associated with an increased likelihood of considering cosmetic procedures [23, 24, 26]. About the social causes of the tendency for facial cosmetic surgery, “having a successful marriage” had the lower medium effect. Several studies show that the mean age of marriage has increased, and the girls’ minds about marriage have changed, and many girls no longer consider marriage as a primary goal in their lives. It means the impact on opposite genders and beauty has their importance, but not only for increasing the chance of better marriage [27, 28].

According to the present study, individuals who apply for rhinoplasty have a lower conscientiousness score than those who do not apply for surgery. Also, the findings of our study showed that people with a desire for cosmetic surgery have a higher flexibility score (desire for new experiences) than the group that does not. They show that they are not applying for surgery.

The results of our study on “openness” were similar to those of Dons et al. They showed in their research that perfectionistic characteristics and passion for experiences such as cosmetic treatment and cosmetic surgery are directly related [29]. The results of the present study regarding agreeableness and compatibility were consistent with the results of Darajati et al.’s study (2012) [30]. Based on this finding, people with more agreeableness and compatibility have less desire for rhinoplasty. Psychological studies have shown that people with lower agreeableness usually step towards being more role models in society, and these people are less self-righteous and agreeable. Therefore, it can be expected that the candidates who undergo cosmetic surgery get a lower score on this test than those who do not apply for surgery [30].

Our study results are different from those of Swamy et al [31]. Based on this study, people with higher conscientiousness are more likely to perform cosmetic surgery. People with more conscientiousness are mainly considered to be strong-willed and pragmatic people. These people try to achieve more success in their profession, which may be due to their obsession with more persistent pragmatism in some cases [31]. The results of this study are similar to those of Pavan et al. (2006), in which the subject group scored lower in conscientiousness and responsibility than the control group [32]. The neuroticism item in our study showed a statistically significant difference between the case and control groups. Studies have shown that neurotic people are generally more dissatisfied with their body image, seem to have emotional stability and express less emotion. Also, unpleasant feelings are expressed more in them. The combination of these factors causes these people to evaluate their physical beauty negatively [33].

The personality types of people are divided into two groups, introverts, and extroverts, based on the theories of the psychology of people. Some scientists have introduced subcategories for it. They enjoy working independently more. They are usually not very social; they prefer individual hobbies and sports; on the other hand, the extrovert type is more interested in group work. Their decisions are faster, and most introverts talk. They also prefer group work and stronger social relationships [34].

One of the strengths of our study was matching the samples with each other. In this study, considering the high rate of cosmetic surgery in women and the fact that men are less inclined to do this, we have selected the entire population from single women permanently living in a city. It makes the samples much more similar to each other in terms of personality structure, and this helps to understand more psychological factors. One of the limitations of our study was the lack of information about the economic status of the people. Because socioeconomic factors significantly impact a person’s decision-making, to limit this matter, we tried to increase the similarity between the people by sampling from one city and being in a hospital center to the point where they have fewer economic differences. Another limitation of the present study was the lack of men in this study. The author eliminates men from the study due to their small number but recommends running a study on these groups in the future.

The authors suggest that more studies be conducted by considering both genders and examining other psychological tests based on socioeconomic variables to identify better the factors on people’s decisions in the beauty field.

Conclusion

The results of the present study revealed that psychosocial factors affect the participants’ tendency for cosmetic rhinoplasty. Determining and identifying psychological pressures and providing individual and psychological support can prevent the incidence of unnecessary rhinoplasty. This measure can lead to the control of unnecessary surgical cases and avoid wasting time and money on it. More studies are recommended to learn more about psychology and its role in cosmetic surgery.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by Qazvin University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.QUMS.REC.1400.359).

Funding

This research was extracted from general practitioner thesis of Mona Akhondi, approved by School of Medicine, Qazvin University of Medical Sciences.

Authors contributions

Study design, statistical analysis and writing manuscript: Reza Emrani; Data collection: Mona Akhondi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate all participants and the hospital staff where the research was conducted.

References

Cosmetic surgery is a procedure not because of medical needs but primarily to create beauty. Rhinoplasty is a challenging procedure in plastic surgery because it entails many unnecessary demands. The request for rhinoplasty is rising, and it is one of the top five surgical cosmetic procedures worldwide. Cosmetic rhinoplasty is a surgery used to change the nose’s appearance to look more beautiful. The big difference between general rhinoplasty and cosmetic rhinoplasty lies in an individual’s demand to change the shape of the nose for more satisfaction, which is generally based on social or psychological demands [1, 2].

Combining aesthetics and cosmetic procedures with technological and medical advancements has transformed beauty from an entirely natural and inconvertible concept to an accessible process, primarily through some medical surgery, including rhinoplasty [3]. Consequently, beauty has become more accessible to everyone in these days. Iran is one of the countries with a high demand for cosmetic rhinoplasty worldwide. One percent of the world’s population belongs to Iran, but 5% of the world’s beauty surgeries are performed in Iran. The inclination toward various cosmetic surgeries has increased worldwide; for example, millions of cosmetic surgeries are performed annually in the United States [4, 5].

In some parts of the world, cosmetic surgery is becoming more popular because it is recognized as a social fashion, and maybe this phenomenon is more influenced by the pressure of media, especially the Internet and social networks [6].

Rhinoplasty aims to improve patients’ quality of life (QoL) and self-satisfaction with their appearance. Successful rhinoplasty procedures typically enhance people’s QoL regarding their physical health, self-confidence, and satisfaction [7, 8].

It is of medical interest to evaluate the psychosocial functioning of volunteers for rhinoplasty and identify their psychological effects. Understanding the psychological factors that create demand for this procedure is very important, considering that cosmetic surgery has a high cost, lacks insurance coverage, and has minimal impact on physical health. In addition, it should be remembered that rhinoplasty has its risks. Many surgeons claim that almost all cosmetic surgeries, including rhinoplasty, have side effects, and practically, many of them are irreversible. These effects include the psychological and even social harm brought on by unsuccessful procedures, such as anxiety and obsession. As a result, finding candidates for surgery who lack the necessary psychological stability is always of interest to surgeons. Also, knowing the psychological factors affecting surgical candidates is of high value for surgeons and doctors [9, 10, 11, 12].

Considering the increasing demand for cosmetic surgery and the importance of knowing people’s psychological structures, this study was performed in Qazvin, Iran, in 2022. The results of this research can be effective in using methods to prevent unnecessary cosmetic surgeries because performing unnecessary surgeries can cause mental stress for the individual, waste money in society, and produce unrealistic needs in health. This study aimed to evaluate different determinants of the patient’s psychosocial functioning that might affect the outcome of rhinoplasty surgery.

Materials and Methods

In this case-control study, 228 volunteers participated in a special hospital for rhinoplasty in Qazvin in 2022. The study’s sample size was estimated at a minimum of 81 according to similar studies and based on the formula of case-control studies (α=0.05, β=0.20).

The inclusion criteria were single women who voluntarily applied for rhinoplasty treatment without therapeutic indication and have a friend who is the same as her in terms of age, gender, education, and level of income but who does not request rhinoplasty, lacks a history of specific mental disorders (self-express), is Iranian, and can speak Persian. To match the cultural and, to some extent, genetic factors, all selected participants in this study were only from the permanent residence of Qazvin. All samples were chosen from volunteers who had applied to a particular hospital for rhinoplasty.

After the volunteers entered the study, we reviewed their files to ensure that the surgery was done only for cosmetic purposes and not for medical needs. The study objectives and method were described for the volunteers, and informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study questionnaire was completed during a face-to-face meeting.

After designing the questionnaire to assess its validity, the questions were evaluated by experts in cosmetic surgery and psychology (two psychologists, two oral and maxillofacial surgeons, one medical doctor, three specialist dentists, and one faculty member). The content validity index (CVI=0.74) and content validity ratio (CVR=0.59) of the items were validated, and to determine the reliability of the questionnaire, the coefficient of reliability (Cronbach α) was calculated. For this purpose, the questionnaire was provided to 22 persons in the study population. Finally, the reliability coefficient for this questionnaire was estimated at 0.83.

The data collection tool was a research-made questionnaire containing 3 parts. The first part comprised demographic questions, including age, job, marital status, and level of education. The second part was on the psychosocial causes of the tendency for cosmetic rhinoplasty, a researcher-made questionnaire consisting of 9 questions. It was based on a 3-point scale (agree, no idea, disagree). Therefore, choosing “agree” indicated the greater effect of psychosocial factors on the tendency for rhinoplasty.

The third tool used in this research was the NEO-FFI (Neo-five factor inventory) questionnaire. NEO-FFI questionnaire has 60 questions that assess the five personality traits of “openness,” “agreeableness,” “nervousness,” “conscientiousness,” and “extroversion.” This test has been standardized in many studies and used in Iran. Also, the Cronbach α of this questionnaire was about 0.77 [13].

In this 5-option questionnaire, scoring was done from 0 to 4, with “completely disagree” to “agree” options, and each part had a minimum of 0 and a maximum of 60 marks. The entire questionnaire had a scale between 0 and 240. The questionnaires were completed before the surgery, the volunteers answered them, and the researcher was there to help them in case of ambiguity. The demographic information of volunteers was also obtained. The descriptive statistics and inferential statistics, including analysis of variance to compare multiple groups (age, level of study, and job), and the t-test to compare between two groups (case-control) were performed. The level of significance was set at P>0.05. Analysis was done by using SPSS software, version 25.

Results

Two hundred twenty-eight volunteers participated in this study (114 cases, 114 controls). Age, job, and level of education were considered as variables in the mean score of variables in two groups (case and control) to compare the effect of these variables. The Mean±SD age of the participants was 24.6±3.6 years (case, 24.2; control, 25). All subjects were single. Finally, in terms of academic status, students were the most (case, 43; control, 40) group followed by those having diploma (cases, 34; control, 32). The highest frequency according to job category belonged to the students (cases 43, control 40) group, followed by the non-governmental employee group (case, 33; control, 31) (Table 1).

There were no significant differences among participants in terms of job and level of education. Analysis of variance was used to compare between groups (only on the case group).

Regarding the social causes of the tendency for cosmetic procedure, “rhinoplasty improves self-confidence (101[88.5%]),” “rhinoplasty improves beauty (97[85%])” and “peer pressure” (86[74.5%]) were the most frequent response of the participants and rhinoplasty is fashionable had least frequency (42[36.8%]) response.

According to the results, the participants’ answers in the case and control groups on the “peer pressure” and “it’s a new experience in life” were not significant. There were differences in other domains between case and control groups, and the differences were significant. All results are presented in Table 2.

According to the result of the Neo test, three domains (openness, extraversion, and agreeableness) were higher and more significant in the case group. Neuroticism was higher in the case group but was not significant. Conscientiousness was significantly higher in the control group (Table 3).

Discussion

The present study was designed to investigate the psychosocial reasons for taking cosmetic rhinoplasty surgery in patients referred to hospitals in Qazvin. The results showed a significant difference between the attitudes of volunteers and non-volunteers regarding rhinoplasty and their psychological characteristics.

Many participants agreed that “self-confidence” was an important psychological factor in performing rhinoplasty and was the most frequently “agree” answer among all domains. This domain referred to the participants’ tendency to appear better in society. With this result, some articles have shown the effect of a lack of self-confidence in performing cosmetic surgery and reported that people with low self-confidence are more seriously faced with the acceptance of others [15].

Also, concentrating on the beauty of the face and peer pressure were in second and third place among the psychosocial factors in performing rhinoplasty. Beauty is essential for women, and we must know that we have a world where physical appearance seems to rule over many social features. These articles also state that women undergo cosmetic surgery as a means of gaining power because beauty is accompanied by power. Beauty enables women to benefit from unequal opportunities in society. Peer pressure is a pivotal determinant factor in making decisions, including cosmetic procedures. Some studies approved the effect of peer pressure on deciding on cosmetic procedures [16-20, 25]. The domain “impact on the opposite gender” also had a higher score in the present study. Many studies showed that women have more emotional tendencies than men, and their attractiveness is necessary for the opposite gender [21, 22]. The issue of “new experience in my life” and internet pressure was also raised in one of the questions with higher positive answers. A study in Saudi Arabia showed that media, including social networks, greatly impacted people in our time. Reviewing cosmetic surgery-related materials on the internet and spending more time on social media are associated with an increased likelihood of considering cosmetic procedures [23, 24, 26]. About the social causes of the tendency for facial cosmetic surgery, “having a successful marriage” had the lower medium effect. Several studies show that the mean age of marriage has increased, and the girls’ minds about marriage have changed, and many girls no longer consider marriage as a primary goal in their lives. It means the impact on opposite genders and beauty has their importance, but not only for increasing the chance of better marriage [27, 28].

According to the present study, individuals who apply for rhinoplasty have a lower conscientiousness score than those who do not apply for surgery. Also, the findings of our study showed that people with a desire for cosmetic surgery have a higher flexibility score (desire for new experiences) than the group that does not. They show that they are not applying for surgery.

The results of our study on “openness” were similar to those of Dons et al. They showed in their research that perfectionistic characteristics and passion for experiences such as cosmetic treatment and cosmetic surgery are directly related [29]. The results of the present study regarding agreeableness and compatibility were consistent with the results of Darajati et al.’s study (2012) [30]. Based on this finding, people with more agreeableness and compatibility have less desire for rhinoplasty. Psychological studies have shown that people with lower agreeableness usually step towards being more role models in society, and these people are less self-righteous and agreeable. Therefore, it can be expected that the candidates who undergo cosmetic surgery get a lower score on this test than those who do not apply for surgery [30].

Our study results are different from those of Swamy et al [31]. Based on this study, people with higher conscientiousness are more likely to perform cosmetic surgery. People with more conscientiousness are mainly considered to be strong-willed and pragmatic people. These people try to achieve more success in their profession, which may be due to their obsession with more persistent pragmatism in some cases [31]. The results of this study are similar to those of Pavan et al. (2006), in which the subject group scored lower in conscientiousness and responsibility than the control group [32]. The neuroticism item in our study showed a statistically significant difference between the case and control groups. Studies have shown that neurotic people are generally more dissatisfied with their body image, seem to have emotional stability and express less emotion. Also, unpleasant feelings are expressed more in them. The combination of these factors causes these people to evaluate their physical beauty negatively [33].

The personality types of people are divided into two groups, introverts, and extroverts, based on the theories of the psychology of people. Some scientists have introduced subcategories for it. They enjoy working independently more. They are usually not very social; they prefer individual hobbies and sports; on the other hand, the extrovert type is more interested in group work. Their decisions are faster, and most introverts talk. They also prefer group work and stronger social relationships [34].

One of the strengths of our study was matching the samples with each other. In this study, considering the high rate of cosmetic surgery in women and the fact that men are less inclined to do this, we have selected the entire population from single women permanently living in a city. It makes the samples much more similar to each other in terms of personality structure, and this helps to understand more psychological factors. One of the limitations of our study was the lack of information about the economic status of the people. Because socioeconomic factors significantly impact a person’s decision-making, to limit this matter, we tried to increase the similarity between the people by sampling from one city and being in a hospital center to the point where they have fewer economic differences. Another limitation of the present study was the lack of men in this study. The author eliminates men from the study due to their small number but recommends running a study on these groups in the future.

The authors suggest that more studies be conducted by considering both genders and examining other psychological tests based on socioeconomic variables to identify better the factors on people’s decisions in the beauty field.

Conclusion

The results of the present study revealed that psychosocial factors affect the participants’ tendency for cosmetic rhinoplasty. Determining and identifying psychological pressures and providing individual and psychological support can prevent the incidence of unnecessary rhinoplasty. This measure can lead to the control of unnecessary surgical cases and avoid wasting time and money on it. More studies are recommended to learn more about psychology and its role in cosmetic surgery.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by Qazvin University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.QUMS.REC.1400.359).

Funding

This research was extracted from general practitioner thesis of Mona Akhondi, approved by School of Medicine, Qazvin University of Medical Sciences.

Authors contributions

Study design, statistical analysis and writing manuscript: Reza Emrani; Data collection: Mona Akhondi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate all participants and the hospital staff where the research was conducted.

References

- Dean NR, Foley K, Ward P. Defining cosmetic surgery. Australasian Journal of Plastic Surgery. 2018; 1(1):95-103. [Link]

- Pressler MP, Kislevitz ML, Davis JJ, Amirlak B. Size and perception of facial features with selfie photographs, and their implication in rhinoplasty and facial plastic surgery. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2022; 149(4):859-67. [DOI:10.1097/PRS.0000000000008961] [PMID]

- Zuo KJ, Saun TJ, Forrest CR. Facial recognition technology: A primer for plastic surgeons. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2019; 143(6):1298e-306e. [DOI:10.1097/PRS.0000000000005673] [PMID]

- Najjarzadehghalati F, Gradmann C, Kaboodkhani R. A qualitative study of Iranian candidates’ awareness, expectations and motivational factors related to nose job surgery (Rhinoplasty). Electronic Journal of General Medicine. 2022; 19(2):em353. [Link]

- Coombs DM, Lanni MA, Fosnot J, Patel A, Korentager R, Lin IC, et al. Professional burnout in United States plastic surgery residents: Is it a legitimate concern? Aesthetic Surgery Journal. 2020; 40(7):802-10. [DOI:10.1093/asj/sjz281] [PMID]

- Mozaffari Niya N, Kazemi M, Abazari F, Ahmadi F. Iranians’perspective to cosmetic surgery: A thematic content analysis for the reasons. World Journal of Plastic Surgery. 2019; 60(1):69-77. [DOI:10.29252/wjps.8.1.69] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Di Rosa L, Cerulli G, De Pasquale A. Psychological analysis of non-surgical rhinoplasty. Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. 2020; 44(1):131-8. [DOI:10.1007/s00266-019-01538-8] [PMID]

- Sarwer DB. Body image, cosmetic surgery, and minimally invasive treatments. Body Image. 2019; 31:302-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.bodyim.2019.01.009] [PMID]

- Shauly O, Calvert J, Stevens G, Rohrich R, Villanueva N, Gould DJ. Assessment of wellbeing and anxiety-related disorders in those seeking rhinoplasty: A crowdsourcing-based study. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery Global Open. 2020; 8(4):e2737. [DOI:10.1097/GOX.0000000000002737] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Brucoli M, Baena RRY, Boffano P, Benech A. Psychological profiles in patients undergoing orthognathic surgery or rhinoplasty: A preoperative and preliminary comparison. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2019; 23(2):179-86. [DOI:10.1007/s10006-019-00758-1] [PMID]

- Wu Y, Mulkens S, Alleva JM. Body image and acceptance of cosmetic surgery in China and the Netherlands: A qualitative study on cultural differences and similarities. Body Image. 2022; 40:30-49. [DOI:10.1016/j.bodyim.2021.10.007] [PMID]

- Hostiuc S, Isailă OM, Rusu MC, Negoi I. Ethical challenges regarding cosmetic surgery in patients with body dysmorphic disorder. Healthcare (Basel). 2022; 10(7):1345. [DOI:10.3390/healthcare10071345] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Joshanloo M, Daemi F, Bakhshi A, Nazemi S, Ghafari Z. Construct validity of NEO-personality inventory-revised in Iran. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology. 2010; 16(3):220-30. [Link]

- Ghahremani L, Motevasel M, Fararooei M, Rakhshani T. Mental health in rhinoplasty applicants, before and after surgery. Archives of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy. 2019; 4(1):45-51. [DOI:10.12740/APP/106077]

- Ip KT, Ho WY. Healing childhood psychological trauma and improving body image through cosmetic surgery. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2019; 10:540. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00540] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Perrotta G. The concept of altered perception in “body dysmorphic disorder”: The subtle border between the abuse of selfies in social networks and cosmetic surgery, between socially accepted dysfunctionality and the pathological condition. Journal of Neurology, Neurological Science and Disorders. 2020; 6(1):001-7. [DOI:10.17352/jnnsd.000036]

- Radman M, Pourhoseinali L. Effect of rhinoplasty on changing body images in candidates for surgery. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care. 2022; 11(9):5535-9. [DOI:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_2116_21] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Zojaji R, Sobhani E, Keshavarzmanesh M, Dehghan P, Meshkat M. The association between facial proportions and patient satisfaction after rhinoplasty: A prospective study. Plastic Surgery. 2019; 27(2):167-72. [DOI:10.1177/2292550319826097] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Bader D. Picturing female circumcision and female genital cosmetic surgery: A visual framing analysis of Swiss newspapers, 1983-2015. Feminist Media Studies. 2019; 19(8):1159-77. [DOI:10.1080/14680777.2018.1560348]

- Bonell S, Austen E, Griffiths S. Australian women’s motivations for, and experiences of, cosmetic surgery: A qualitative investigation. Body Image. 2022; 41:128-39. [DOI:10.1016/j.bodyim.2022.02.010] [PMID]

- Gierczuk D, Wójcik Z. Physical fitness of highly qualified female and male wrestlers of various sports levels. Journal of Physical Education and Sport. 2023; 23(6):1488-94. [DOI:10.7752/jpes.2023.06182]

- Baez S, Flichtentrei D, Prats M, Mastandueno R, García AM, Cetkovich M, et al. Men, women… who cares? A population-based study on sex differences and gender roles in empathy and moral cognition. Plos One. 2017; 12(6):e0179336. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0179336] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Song S, Gonzalez-Jimenez H, Belk RW. Extending Diderot unities: How cosmetic surgery changes consumption. Psychology & Marketing. 2021; 38(5):745-58. [DOI:10.1002/mar.21463]

- de Vries DA, Peter J, Nikken P, de Graaf H. The effect of social network site use on appearance investment and desire for cosmetic surgery among adolescent boys and girls. Sex Roles. 2014; 71:283-95. [DOI:10.1007/s11199-014-0412-6]

- Chen J, Ishii M, Bater KL, Darrach H, Liao D, Huynh PP, et al. Association between the use of social media and photograph editing applications, self-esteem, and cosmetic surgery acceptance. JAMA Facial Plastic Surgery. 2019; 21(5):e190328. [DOI:10.1001/jamafacial.2019.0328] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Arab K, Barasain O, Altaweel A, Alkhayyal J, Alshiha L, Barasain R, et al. Influence of social media on the decision to undergo a cosmetic procedure. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery Global Open. 2019; 7(8):e2333. [DOI:10.1097/GOX.0000000000002333] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Au A. Framing the purchase of human goods: Cosmetic surgery consumption in capitalist South Korea. Symbolic Interaction. 2023; 46(1):72-93. [DOI:10.1002/symb.623]

- Miller L. Deracialisation or body fashion? Cosmetic surgery and body modification in Japan. Asian Studies Review. 2021; 45(2):217-37. [DOI:10.1080/10357823.2020.1764491]

- Dons F, Mulier D, Maleux O, Shaheen E, Politis C. Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) in the orthodontic and orthognathic setting: A systematic review. Journal of Stomatology, Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2022; 123(4):e145-52. [DOI:10.1016/j.jormas.2021.10.015] [PMID]

- Darajati AA, Rezaee O. [Predicting the symptoms of body dysmorphic disorder based on the amount of use of social networks and defense mechanisms in the clients of cosmetic surgery centers (Persian)]. Rooyesh-e-Ravanshenasi Journal (RRJ). 2023; 11(11):63-72. [Link]

- Swamy V, Phelan AL, Abdelrahman A, Albert MG. Limited incision rhinoplasty: An approach for all primary and revision cases. Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. 2024; 48(3):407-12. [DOI: 10.1007/s00266-023-03778-1] [PMID]

- Pavan C, Simonato P, Marini M, Mazzoleni F, Pavan L, Vindigni V. Psychopathologic aspects of body dysmorphic disorder: A literature review. Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. 2008; 32:473-84. [DOI:10.1007/s00266-008-9113-2] [PMID]

- McGrath LR, Oey L, McDonald S, Berle D, Wootton BM. Prevalence of body dysmorphic disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Body Image. 2023; 46:202-11. [DOI:10.1016/j.bodyim.2023.06.008] [PMID]

- Kawamoto T. Online self-presentation and identity development: The moderating effect of neuroticism. PsyCh Journal. 2021; 10(5):816-33. [DOI:10.1002/pchj.470] [PMID]

Type of Study: Original Article |

Subject:

Community Health

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |